Last updated: August 3, 2023

Article

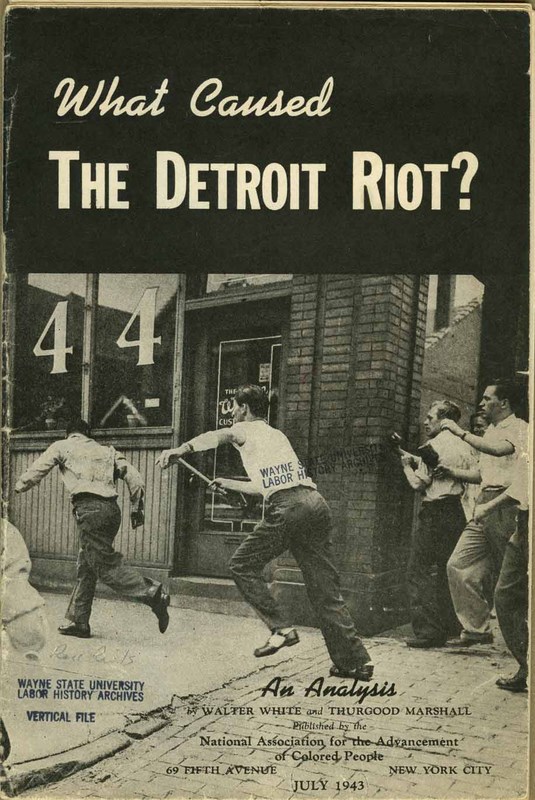

(H)our History Lesson: The Detroit Race Riot of 1943

Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Introduction

This lesson discusses the devastating racial unrest that gripped Detroit in June 1943. It can be taught as part of a unit on World War II and the home front, the history and progression of civil rights for African Americans, and/or place-based learning. This lesson connects to the history of Detroit, Michigan, and to the state park site of Belle Isle. The Belle Isle Bridge is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The lesson has three readings (one secondary background reading and two primary sources) along with two activity choices.

Content Warning: The lesson integrates historical primary sources that use racist language. It is important to prepare students and share with them the purpose of examining sources in learning about racial injustice. Learning from these artifacts can help us to better understand systems of oppression, both past and present.

Grade Level Adapted For

Grades 6 - 12

Lesson Objectives

Students will be able to . . .

-

Examine and evaluate primary and secondary sources to ask and answer questions, that lead to answering the inquiry question.

-

Describe evidence and impacts of racial discrimination and violence in the home front city of Detroit during World War II.

-

Use historical source information to a) share their opinion on reparations related to the race riot, and/or b) inform others of the history of the race riot.

Essential Question

Using Detroit as an example, what was the impact of racial discrimination on the home front during World War II?

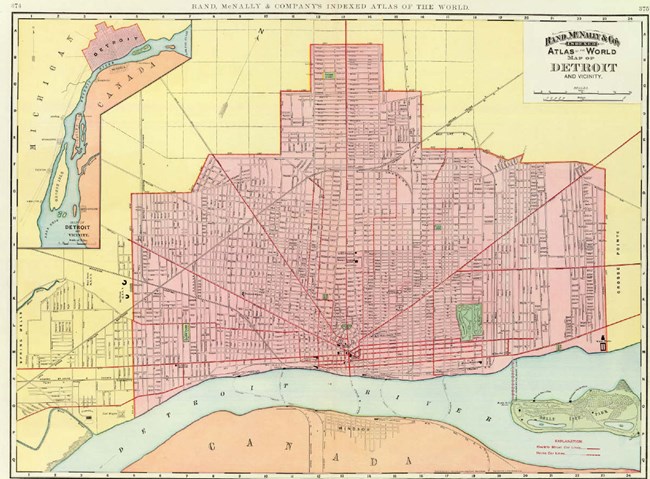

David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford Libraries

Background Readings

The primary and secondary source readings below will introduce students to the history of the Detroit Race Riot of 1943.

It is recommended that students understand Reading 1 prior to moving on. Both primary sources later refer to details provided in this reading. Readings 2 and 3 are responses to the Detroit Race Riot. They were published a little over three months apart, in July and October of 1943. In both, the bold and capitalized text is replicated from its original newspaper printing.

The readings can be selected for whole group, individual, or shared reading amongst small groups as a “jigsaw puzzle” format, where groups report out. Activities can be included after the readings, extensions, or during the hour if readings are assigned in advance.

Background Reading 1: Secondary Source

This secondary source reading introduces students to the topics of racial discrimination on the World War II Home Front and the events of the 1943 racial unrest in Detroit.

Excerpt by Sarah Nestor Lane (December 2022)

Background

During World War II the United States battled issues of racism and segregation. The Roosevelt administration and some Americans worried the Axis powers would use racial discrimination issues on the home front to cut away at American unity. Detroit is an example of a city with racial tensions that experienced violence on the home front.

Racial Tension in Detroit

The war brought booming changes to Detroit. Industrial growth attracted thousands of people north to the city, including African Americans seeking employment. African Americans, both men and women, who arrived in Detroit faced discrimination both in their housing and workplaces.

The factories offered employment, but did not provide housing. With the influx of African American workers, white residents in Detroit defended their segregated neighborhoods and schools. Already there was a 60 square block area in town known as “Black Bottom” where second class, subdivided apartments were built. African Americans were forced to live there due to white residents’ pushback and housing discrimination. As more employees continued to come to Detroit, space ran out in the existing “Black Bottom.”

In 1941 the city approved a plan for a 200-unit site, intended for African American families and defense workers. This site was next to a predominately white neighborhood. The plan was called the Sojourner Truth Housing Project. There were protests and clashes between angry, nearby white residents and authorities. The local white population did not want to live near African Americans. Government planners did not find an alternate site and, in 1942, a mob of over one thousand white residents picketed against the arrival of African American neighbors. The Michigan National Guard was mobilized to move the first African American families into the housing project.

There was racism within the worksites as well. At factories, white workers used several tactics to protest working alongside African Americans. White workers stopped production in a strike to protest promotions of African American coworkers (June 1943) and there were intentional production slowdowns. The discrimination African Americans faced in housing, employment, rationing, and more led to racially motivated fights and resentment in the city of Detroit.

Belle Isle, June 20, 1943

Belle Isle was a popular, integrated amusement park. On the evening of June 20, 1943, at least one racially motivated fist fight started. This led to fights breaking out across the island between whites and African Americans. White sailors from a nearby Naval Armory also got involved. Fighting spread to the bridge and ferry docks leading to the mainland city of Detroit. White residents blocked the main entrance of the bridge to prevent African Americans from returning from Belle Isle. It took many hours for police to gain control. Order was restored around midnight on Belle Isle. Yet, by the early morning of June 21, violence had spread from Belle Isle into the main city.

Tensions escalated with news and rumors of racial violence at Belle Isle Bridge. African Americans at a social club in the city were told that whites had thrown an African American woman and her baby off the Belle Isle Bridge. Whites heard that an African American man had assaulted a white woman near the bridge. These rumors were in addition to the news of the fights on Belle Isle itself. Both rumors led to riots in the city. Near Roxy Theatre, a mob of white men started attacking African American men. These African American men were exiting city buses to get to work. The mob pulled African American drivers from their cars, turned the vehicles over, and set them on fire. Meanwhile, on Hastings Street, an African American group of people began looting white businesses.

Witness accounts shared how police sprayed entire buildings with gunfire. They beat or shot African Americans, even when they were running away. Police claimed the shootings were justified due to looting. Four times as many African Americans were arrested as white persons. Twenty-five African Americans were killed, 17 of them by police. Nine white persons died, none at the hands of police. This made for a total of 34 people killed. The authorities reported approximately 675 people injured.

Eventually, Mayor Edward Jeffries called for help from national troops. Six thousand soldiers arrived with weapons and tanks at the order of President Roosevelt. They cleared main thoroughfares, firing no shots. There were approximately $2 million in damages to the city (equivalent to approximately $30 million in 2022).

Response

Local and national public debate ensued. Questions arose on the local response of police and community leaders during and after the riot, the riot’s causes, and what further action should be taken. The press at that time reported on the news of death and violence--both at home and abroad.

Background Reading 2: Primary Source

This primary source reading is an excerpt article from the Detroit Evening Times, published on July 1, 1943 (page 3). The article shares a statement by Dr. James J. McClendon, the president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, a civil rights group.

From Detroit Evening Times (Detroit, MI), Jul. 1, 1943, pg. 3.

Criticizing Mayor Jeffries’ report to council on the race riots, Dr. James J. McClendon, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, today reiterated his demands for a grand jury investigation and charged that a portion of the mayor’s report was inflammatory and hardly conducive to harmony.

In a two-page, formal answer addressed to the mayor, McClendon declared:

“Your ‘white paper’ can be called a masterpiece of explanation. Your statement that you are tired of ‘Negro leaders who insist that their people do not and will not trust policemen and the police department’ is inflammatory and does not add to harmony.” . . .

“We do not condone the acts of hoodlums of our race any more than you condone those who overturned cars, ran down the defenseless and enacted other acts of violence on Woodward avenue. Had more police been stationed on Woodward avenue rather than concentrated throughout the Negro area, there would not have formed such a gigantic mob of ‘10,000.’

It takes no crystal gazer to add the scores of Negroes slain by the police or compare the lack of such ‘shoot to kill’ policy on Wood ward avenue.” . . .

. . . McClendon agreed with the mayor that the “underlying factors behind this racial hostility” were not settled by the riots.

Background Reading 3: Primary Source

This primary source reading is an excerpt from an article in the Detroit Free Press from October 24, 1943. The author, James Hosking, reflects on the events of the riot. He then quotes an interview with two researchers, Alfred McClung Lee and Norman Daymond Humphrey, who were publishing a book about the riot.

“Remember . . . June 21, 1943, Detroit, Mich.? The vast majority of Detroiters remember . . . with horror.

For on that day and the night before and the days following, a mighty war machine was slowed, fellow-citizens were murdered, thousands were maimed, and the idea of democracy that a decent world was fighting for was made ludicrous and sinister.

Succeeding events come whispering back like echoes in a canyon: A Mayor’s regime may fall . . . And Harlem explodes . . . The Axis radio crackles gleefully. . . and Michigan spends time and money and needed man-hours in training State Troops to handle the next race riot.

Therein lies the story: The next one and how to make it as impossible as an Axis victory overseas.

The two are related, of course, as Wendell Willkie made clear when he attributed American race riots “to the same basic motivation that actuates the Fascist mind—the desire to deprive some of our citizens of their rights—economic, civil or political.”

Everybody agrees something must be done about this: and so reports are inevitable. We have had them—Mayor’s white papers, Dowling’s attempt to pin blame, Attorney General Biddle’s memorandum to the President, and Negro groups’ published and unpublished accounts. But there was no grand jury to present its report. . .

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The next section consists of an excerpted Q&A with Wayne State University professors Alfred McClung Lee and Norman Daymond Humphrey, whose book about the riots was about to come out.]

". .Who REALLY did the rioting? 'In many ways, this question cannot be answered through characterizing the one-thirtieth of the people of Wayne County—the Mayor said 100,000 men, women, boys and girls, whites and blacks—who actually did the looting, stabbing, shooting, burning, beating, screaming and running.

In many ways, it can be answered only by candidly admitting that we all did the rioting, all Detroiters and all Americans. All did the rioting in the sense that we have done little diminish racial and religious intolerance in this country, to democratize rather than to Balkanize America’s interracial and general inter-group life.'

And they quote the caption printed by the Free Press over a picture of dead bodies at Receiving Hospital: IN THE DEMOCRACY OF THE DEAD, ALL MEN AT LAST ARE EQUAL.” . . .

Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Reading Responses

Considering Readings 1-3

-

What was the significance of Belle Isle?

-

In reading 2, the article mentions a point of agreement between the NAACP president and Detroit mayor was that the root causes of the riot had not been settled. What were some of the root causes? (Hint: refer to reading 1)

-

Extend your thinking: Based on your knowledge of future events, when, or if, do you believe these root causes got “settled?”

-

-

Reading 2 describes “scores of Negroes slain by the police.” Compare this to the details shared in Reading 1. How does reporting bias impact perceptions of historical events?

-

Detroit was nicknamed the “Arsenal of Democracy” due to its industrial prosperity during the war. How does the author’s perspective from Reading 3 contrast with this nickname?

-

Have you heard of, or learned about, the Detroit Race Riot prior to now? Consider why you may or may not have learned about these events. What is its role in relation to learning about World War II?

-

Using the resources, respond to the inquiry question: Using Detroit as an example, what was the impact of racial discrimination on the home front during World War II?

Activities

1. Today’s Debate: Reparations?

Subject integration: Opinion writing, current events, social justice studies

Teacher tip: Response to this can be in a variety of formats, such as oral debate and discussion, recordings, paragraphs, essays, etc. It may also result in further action, should you choose to extend it.

Detroit’s city council released a legislative policy division reply on July 5, 2022, “Re: Identifying survivors of the 1943 Belle Isle Race Riot.”

The following is an excerpt: “Council Member Coleman A. Young II requested the Legislative Policy Division (LPD) to draft a report identifying any survivors of the Belle Isle (Detroit MI) Race Riot of 1943, for the purpose of reparations. Due largely to the passage of time since the 1943 riot, LPD lacks the resources to identify survivors or the identities of all of the victims. That would be a significant research project that would require a substantial dedicated budget that does not exist. . .

However, the victims of the violence have been identified and due to the circumstances surrounding their deaths, it is conceivable – depending on the terms of an eventual reparations program – that a case can be made for reparations by their descendants.”

In a response, share your opinion of this decision. Consider:

-

Why may a council member have made this request?

-

What are barriers to reparations connected to historical events? (In general, and specific to this event.)

-

Do you believe the city council should act? Why? What kind of action, if so?

2. Belle Isle History

Subject integration: Informative writing, writing for an intended audience

Teacher tip: This can be done individually, or in small groups. Consider providing a menu of choices of ways historical content is shared, if students need it (ex. historical markers, audio or walking tour, mural, memorial, pamphlet, additional information, or special tabs added to the Belle Isle website . . .)

Student prompt:

Belle Isle is a park that is about 985 acres and today has features like an aquarium, golf course, historical light house, swimming beach, and more. The Belle Isle Bridge connects to the park land, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. The location is popular with visitors, but they may not know of the events that occurred there in June 1943.

What do you believe would be the best method(s) of sharing this history with visitors? Draft one way (visual, audio, artistic, written . . .) to share the history of the Detroit Race Riot with visitors. Include key information from the lesson readings.

This lesson was written by Sarah Nestor Lane, an educator and consultant with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.