Part of a series of articles titled Civil Rights and Public Education .

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Pierre Samuel Du Pont's Delaware Experiment

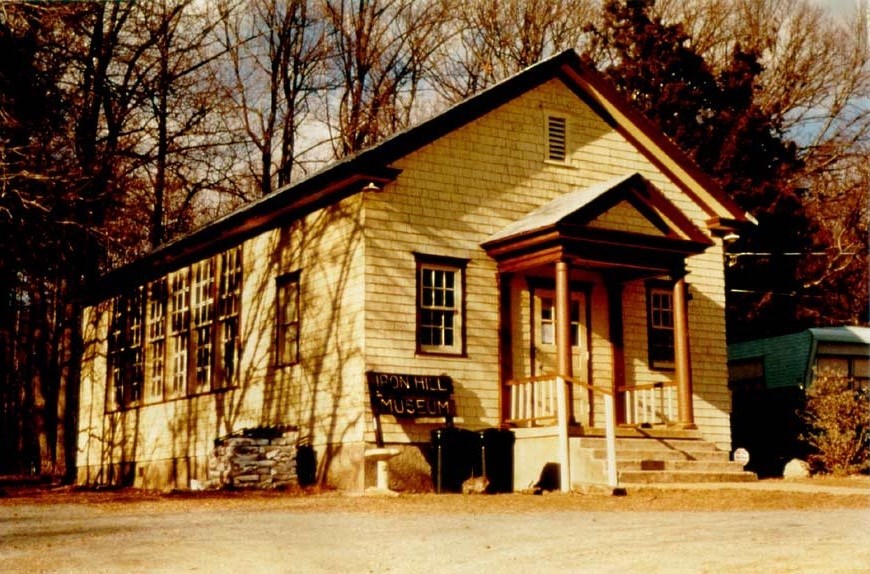

This lesson was adapted by Katie McCarthy from the full-length Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan “Iron Hill School: An African American One-Room School.” For more information on this topic, explore the full lesson plan.

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Students will be able to...

-

Consider the impact racial segregation had on the quality of education available to African American children.

-

Examine the motives and results of Pierre Samuel du Pont's philanthropic efforts on behalf of Delaware's African-American school children.

-

Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of a secondary source.

-

Determine the central ideas or information of a secondary source.

Inquiry Question:

How many students are in your class? How about in your school? Can you imagine if your teacher had to teach students from multiple grades all in one classroom?

Reading:

Background:

Delaware practiced racial segregation well into the 20th century. Segregation restricted African Americans' access to railroad cars, hotels, theaters, and public buildings. African-American children had to attend separate schools with inferior materials and equipment. In 1875 the Delaware state legislature recognized the need to financially support schools for Black students. This funding, provided by property taxes collected from African-American men, was not enough. Schools for Black children continued to be under-funded compared to those in the white districts.

In 1897 the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling stated that segregation was legal as long as the separate spaces were equal. Delaware began to require the equal distribution of state funds among schools for white and Black students. However, school districts still partially depended on property taxes, so African-American schools continued to receive less money than white schools.

Concerned about the poor condition of Delaware's public schools, including those for African-American students, philanthropist Pierre Samuel du Pont decided to donate money to have schools in the state rebuilt. More than 80 African-American schools were constructed with du Pont funding between 1919 and 1928.

Content:

The early 20th century in America, a period characterized by nationwide social reform, is often referred to as the Progressive Era. During this period, more and more people recognized that education was the best guarantee of success for young people. Delaware's educators were eager to reform their schools, which were often old, too small, and in very bad condition. According to a 1915 federal study of the quality of education in the US, Delaware ranked in 39th out of the then 48 states. In 1919 Delaware adopted a new school code. The code established that schools for African Americans would receive some of the money collected from white taxpayers. The new school code also supported the rebuilding of schools for white students. Delaware's new school code required both Black and white children under age 14 to attend school during the school year.

A survey of Black students in Delaware showed that many of the existing schools were difficult to get to. School planners decided that the best solution was to build many small, single-teacher schools. That way, they would be easier to reach. However, no money was allocated for rebuilding schools for African-American children. Concerned about the condition of education, philanthropist Pierre Samuel du Pont decided to help pay to have schools in the state rebuilt.

Pierre Samuel du Pont was a member of the family that established the Du Pont Company in Wilmington, Delaware. The company became a world leader in the explosives industry. In 1919, du Pont resigned as president of the family business. He began devoting much of his time to improving education. He even served on the State Board of Education. Using his own money, du Pont established a two-million dollar trust fund. The fund was used to remodel existing school buildings and construct new ones in Delaware. He designated a large amount of that money to build new schools for African-American children. Between 1919 and 1928 du Pont personally financed the construction of more than 80 schools for Black students.

Many Progressive Era philanthropists believed that a good school building would improve a student's education. Du Pont agreed. Therefore, he wanted to hire the best architect possible. He believed that "a school is a highly specialized type of building," and "experimenting with an architect who is not familiar with the latest ideas on school administration, design and construction is likely to prove very costly."1 He hired James Oscar Betelle, a nationally-known architect of schools.

Betelle made very specific recommendations regarding classroom size and design. The recommended size for a classroom for 40 students was approximately 24 feet wide by 32 feet long. Natural light was considered one of the most important factors for a new school. In addition, every room would have a closet for the storage of books and supplies. The blackboards would hang at the front of the room and on the wall opposite the windows. Seats would be moveable and adjustable. Room would be provided to hang hats and coats. The recommendations also specified play equipment, and a place to prepare hot lunches.

By 1938, after many of the schools for white students and all the schools for Black students had been rebuilt. Delaware advanced to eighth place out of the 48 states in terms of the quality of its public education system. In 1926, when asked by the editor of Afro-American Magazine why he had funded these schools, du Pont replied:

If the Delaware experiment proves satisfactory, which I am sure it will, it will be a great incentive to go ahead more quickly in other States....The progress of Delaware schools will bear watching, for on their success must hang the fate of Negro public school education in the United States for many years.2

Reading Questions:

-

How did the 1919 Delaware school code impact learning for children in Delaware?

-

Who was Pierre Samuel du Pont and why did he undertake what he called the "Delaware experiment"? Can the benefits of du Pont's gift be measured? If so, how?

-

Why did du Pont want to hire a nationally-known architect of schools?

-

Why was it thought necessary to provide several small schools for African American children rather than fewer, larger schools?

-

What are some of the features of progressive architecture described in the reading? Why do you think these were considered important?

Activity:

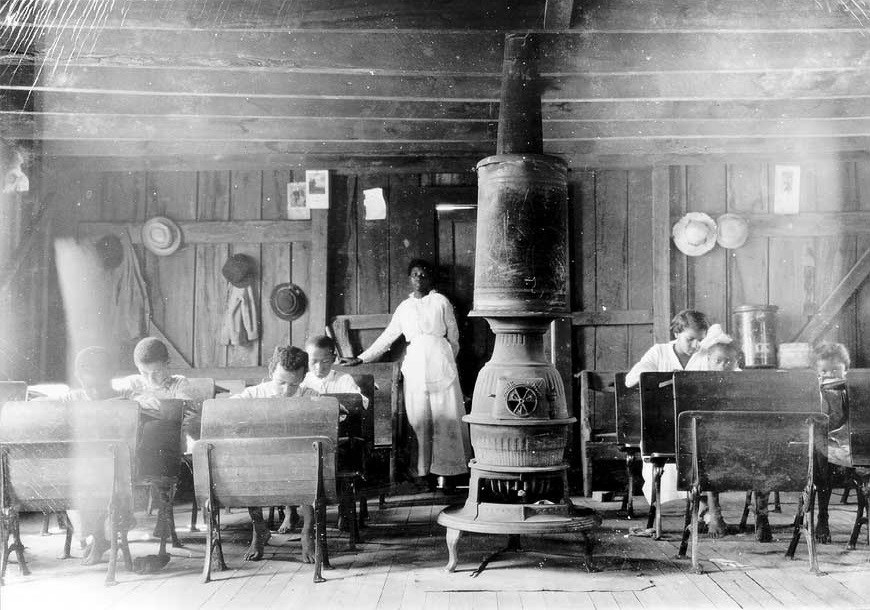

In this activity, students will compare and contrast two different schools. Students will read excerpts describing Iron Hill school in Delaware, which was built in 1923 using funding from Pierre Samuel du Pont, and examine a photograph of a school in Kentucky built in 1875. Have students closely examine each primary source, noting the furniture, lighting, heating, architecture etc. After students examine the resources, lead a conversation discussing how (a) segregation and (b) du Pont funding impacted the quality of schools and education for African American students.

Iron Hill School's Progressive Elements

The following quotes are excerpts from oral history interviews conducted in 1995 with former Iron Hill School students:

I thought it was just wonderful, beautiful. I think I had...gratitude towards Mr. du Pont beyond the architecture. The thought that he would build black people such a building....There's always a soft spot in my heart for the du Pont family, the good that they have done, and Pierre S. du Pont was the one....I just was elated at the building, but I think I was always thinking of how wonderful it was that he gave it to us.

--Dorothy Copper

There were lights and we had shades to the windows....It was always clean, the building was always clean, bright, and cheerful....I never remember having trouble seeing because the shades were adjustable. On cloudy days maybe they were all the way up so you would have more light.

--Rebecca Freeman

I can remember what I would call a pot belly stove, a big furnace, used for heating and also used sometimes for heating our hot lunches....The stove was cast iron.... We had to be awfully careful going up and putting the pots we were going to cook on top of the stove....It would be awful cold, and when it got cold out it would take a lot of coal to heat this building....The coldest part was over there by the windows because these windows used to push out. The big kids would be over there and the smaller kids would be next to the fire.

--Reverend Allen O. Smith

I think, when I first began, I remember the stove. As time went on it seems like there was a heater there....I don't know that it worked all the time, but there was, I believe, a heater there, a furnace....We also sometimes prepared special meals there. The teacher would let the older children themselves prepare meals there, a pot of soup or something someone had sent in for us to have a hot meal for the day....It was a big pot belly stove--it got really hot, but you could set a pot on the top.

--Rebecca Freeman

After students compare the pictures and quotes, have them consider what the children who went to school in these schools perceived, what they knew about or believed, and what they might have cared about. How does answering these questions help us understand more about the schools du Pont funded and the students who attended them?

Wrap-up:

-

How do you think where someone learns affects how well they learn? Would it be easy for you to learn if your classroom was too cold, or too hot, or too dark?

-

How do you think students felt during the first days in their new school?

-

Who built your school? How was it funded?

-

Are there people known as philanthropists in your community? What causes do they donate to?

-

What does this lesson make you curious to explore?

Footnotes:

1 Pierre S. du Pont to Board of Education, October 15, 1932, Pierre S. du Pont Papers, Longwood Manuscripts, Group 10, Series A, File 712, Box 5 (Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware).

2 Pierre S. du Pont to Carl Murphy, March 1, 1926, Pierre S. du Pont Papers, Longwood Manuscripts, Group 10, Series A, File 712, Box 3 (Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware).

Reading 1 was adapted from Susan Brizzolara Wojcik, "Iron Hill School Number 112C," (New Castle County, Delaware) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, 1995; and from the Papers of Pierre Samuel du Pont (Courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library).

Additional Resources:

Library of Congress

The American Memory collection offers a wide variety of resources about the history of one-room schools, including photographs and oral histories of people who attended them. Start with the search engine, being sure to choose "Match this exact phrase" before you enter "one room school."

Tags

- progressive era

- segregated schools

- segregation

- education history

- african american history

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- delaware

- delaware history

- art and education

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- hour history lessons

- educational activity

- education

- schoolhouse

- schools

- civil right

- civil rights

- gilded age

- twhplp

- ga aah

- etc aah

Last updated: May 11, 2023