Part of a series of articles titled Women's History to Teach Year-Round.

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Madam C. J. Walker, African American Millionaire, Philanthropist, Activist

Introduction

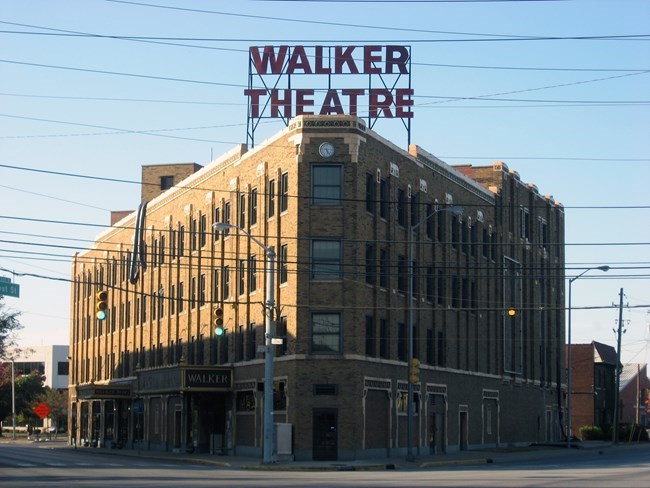

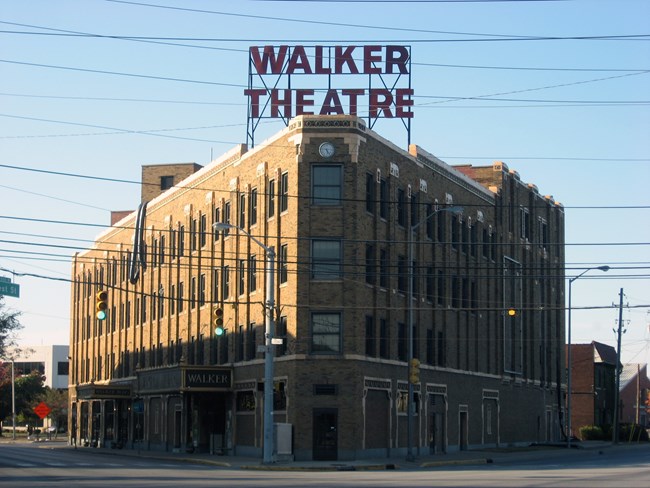

"Women's History to Teach Year-Round" provides manageable, interesting lessons that showcase women’s stories behind important historic sites. In this lesson, students explore the life of Madam C. J. Walker, a Black entrepreneur, and her success in business and social good, as exemplified by the Madam C. J. Walker Building in Indianapolis, Indiana.

This lesson was adapted by Talia Brenner and Katie McCarthy from the Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan, “Two American Entrepreneurs: Madam C.J. Walker and J.C. Penney.” If you're interested in more information and activities on this topic, explore the full lesson plan.

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners, but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Learners will be able to...

-

Describe Madam C.J. Walker’s life, entrepreneurship, and philanthropy.

-

Understand the challenges, including racism, that Madam C.J. Walker faced in beginning her business.

-

Determine the central ideas or information from both primary and secondary sources and provide an accurate summary of these sources.

-

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose.

Inquiry Question:

At the height of her success, Madam C.J. Walker began planning for a community center for African Americans in Indianapolis. Her daughter later completed the project and constructed the Walker Building, today known as Walker Theatre. Madam C.J. Walker was an entrepreneur, or someone who starts and runs their own business. What kinds of challenges do entrepreneurs face? Do all entrepreneurs face the same challenges?

Background

The late nineteenth and early twentieth century was a time of enormous racism against African-Americans in the United States. A large majority of Black Americans lived in the rural South and were economically exploited by white property owners. Racist voting laws and violence from white vigilantes kept African-Americans from gaining political power.

Despite these conditions, a small number of African-Americans were able to earn money and fame. Madam C. J. Walker, a Black entrepreneur, built an enormously successful enterprise in hair and beauty products designed specifically for Black women. Walker used her position of influence to advocate for African-Americans.

Reading

Madam Walker was born as Sarah Breedlove in December 1867, in Delta, Louisiana. Her parents, Minerva and Owen Breedlove, had been enslaved. During Sarah’s youth, they worked as sharecroppers on a cotton plantation and lived in a one-room cabin. Sharecropping created a cycle of debt where families had to work for very little pay. They could not build up any savings to leave. Many sharecroppers worked for the people who had once enslaved them. The sharecropping system was common in the South after the Civil War.

By the time she was five, Sarah had learned to carry water to field hands and plant cotton seeds. For a dollar a week she washed white people's clothes with strong lye soap, wooden sticks, and washboards. By the time she was seven, both of Sarah's parents had died, and she moved in with her older sister Louvenia. A few years later, after a failure of the cotton crop, the sisters moved across the river to Vicksburg, Mississippi. There they worked as washerwomen and domestic servants.

At 14, Sarah married Moses McWilliams to escape abuse from her brother-in-law. At 17, she gave birth to her only child, a daughter named Lelia. Moses died in 1887, when Sarah was only 19. She and her young daughter set off for St. Louis. She was told that laundress jobs there were plentiful and fairly well paid. For the next 17 years, Sarah supported herself and her daughter. She mainly worked as a washerwoman, but she also worked as a sales agent for Annie Turnbo, who created hair products for Black women. Sarah had never received a formal education. She was determined to provide her daughter with the opportunity to learn.1 She sent Lelia to both grade school and college.

Now in her thirties, Sarah realized, to her dismay, that her hair was falling out. Inspired by Turnbo's success, Sarah began mixing her own formulas and eventually developed one that worked. She later told a reporter that God had "answered my prayer, for one night I had a dream, and in that dream a big black man appeared to me and told me what to mix up for my hair. Some of the remedy was grown in Africa, but I sent for it, mixed it, put it on my scalp, and in a few weeks my hair was coming in faster than it had ever fallen out. I tried it on my friends; it helped them. I made up my mind I would begin to sell it."2

Because St. Louis already had several cosmetic companies, Sarah decided to move to another city to set up her own business. She chose Denver because she had family who lived there. Sarah arrived in Denver in 1905 with $1.50 in savings. Working as a cook to pay her rent, Sarah spent the rest of her time mixing her hair growth products and selling them door to door. In the early 1900s, many women suffered from hair loss due to scalp disease. Sarah’s products met a demand in the market and the business grew rapidly.

In 1906, Sarah married C. J. Walker, a newspaper salesman she had known from St. Louis. From then on, Sarah began calling herself Madam (sometimes spelled Madame) C. J. Walker, invoking the French title used in the cosmetics and fashion industries.3 As the business expanded, C. J. Walker helped his wife develop marketing and organize a mail-order business.

Madam Walker’s business model involved both mail-order sales and door-to-door sales. Walker’s saleswomen, called “Walker Agents,” did more than just sell products. Walker Agents also gave scalp treatments, styled hair, and did manicures and massages. Working as a Walker agent was empowering for African-American women. Many former schoolteachers, cooks, and washerwomen were able to earn far more money as Walker Agents than they could before. One agent wrote that Walker "opened up a trade for hundreds of colored women to make an honest and profitable living where they make as much in one week as a month's salary would bring from any other position that a colored woman can secure."4

In 1908, Walker moved to Pittsburgh, where she established Lelia College, a training facility for Walker employees. In 1910, Walker decided to move her headquarters to Indianapolis. Indianapolis was the United States' largest inland manufacturing center. It was also home to a thriving African-American community. Madam Walker built a factory, hair and nail salon, and another training school. By 1913, Madam Walker had divorced her husband and placed Lelia as her second-in-command. At Lelia’s urging, Madam Walker also built a beauty salon and training school in Harlem, the center of African-American culture in New York.

Having once lived in desperate poverty, Madam Walker enjoyed her wealth. In 1916 she built her dream house, a mansion in a wealthy community north of New York City. Yet she believed her primary responsibility was in advocating for African-Americans. Through her business, she sold hair products that encouraged Black women to feel proud of their natural hair. Thousands of African-American Walker Agents achieved financial success by selling her products. Walker was also a philanthropist and activist. She donated large amounts of her fortune to African-American organizations and encouraged her employees to donate as well. In 1917, she helped organize a protest after white rioters in East St. Louis massacred dozens of African-Americans.5 That same year, she went to the White House to urge President Wilson to make lynching a federal crime.6

Madam Walker died early, at the age of 51. In her will, she directed two-thirds of her estate’s future net profits to charity organizations. Before she died, Walker had planned to build a new headquarters building in Indianapolis that would also serve as a commercial center for African-Americans. Madam Walker’s daughter, who had changed her name to A’Lelia (ah-LEEL-ya), oversaw the completion of the new Walker Building. When the building was finished in 1927, it indeed fulfilled Madam Walker’s goal of creating a community space. The headquarters of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, the building also housed the Walker Theater, Walker Drug Store, Walker Casino, Walker Beauty Shop, a ballroom, and a coffee shop. African-American doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who had difficulty finding office space in buildings owned by whites rented space in the Walker Building.

Discussion Questions

-

How would you describe Walker’s childhood?

-

Why would African-American women want to work as Walker Agents?

-

What factors do you think made Walker's business so successful? What factors might have hindered its growth, or the growth of other businesses like it?

-

Look up the term “corporate responsibility,” then define it in your own words. How did Walker promote corporate responsibility?

-

In what ways did the Walker Building carry on Madam Walker’s legacy?

1 A'Lelia [Perry] Bundles, “Madam C.J. Walker: Business Savvy to Philanthropy,” eJournal USA 16 no. 6 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State, February 2012), https://photos.state.gov/libraries/amgov/30145/publications-english/Black_Women_Leaders_eJ.pdf, 3.

2 A'Lelia Perry Bundles, Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1991), 35.

3 Bundles, “Madam C.J. Walker: Business Savvy to Philanthropy,” 3.

4 A'Lelia Perry Bundles, "Madame C.J. Walker: Cosmetics Tycoon," Ms. (July 1983), 93.

5 Bundles, “Madam C.J. Walker: Business Savvy to Philanthropy,” 5.

6 Bundles, “Madam C.J. Walker: Business Savvy to Philanthropy,” 5.

Activity 1: Advertising Then and Now

Madam C. J. Walker’s company continued to be successful after her death in 1919. The advertisement below is from the 1930s. Have students observe the advertisement and read the transcript twice. They should then answer the questions below, working either individually or in small groups.

Image: Beauty Advertisement

Courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society, Walker Collection.

Transcript

You, too, may be a fascinating beauty

Perhaps you envy the girl with irresistible beauty, whose skin is flawless and velvety, whose hair has a beautiful silky sheen, the girl who receives glances of undoubted admiration.

You need not envy her. Create new beauty for yourself by using Madam C. J. Walker's famous beauty preparations.

When Madam Walker and her associates started to develop her beauty preparations, which are now used all over the world, they perfected their toiletries step by step.

Each preparation was beyond the point of experiment before it was followed by another. Each preparation's wide use and higher merit were always proved. Today they are unsurpassed.

Try these products and you won't have reason to envy another girl her lovely hair and her charming complexion.

You can obtain any of these marvelous preparations at your nearest druggist or from a Madam C. J. Walker agent (there's one near you) or write the company direct at Indianapolis.

Madam C. J. Walker's Beauty Preparations

Complexion and Toilet Soap--A preservative of beauty--mild and safe for the most tender skin. Perfumed delightfully. 20 cents per large bar.

Vegetable Oil--Antiseptic Soap--A popular-priced household soap of purest vegetable oils. Lathers well in hardest water, removes grease and dirt, yet will not harm a lady's skin. A bargain at 10 cents a bar.

Superfine Face Powder (Brown)--Clinging, velvety smooth, invisible and adorably perfumed. Imparts an olive tint to fair complexions and harmonizes bewitchingly with darker skins. Obtainable in rose-flesh and white. 50 cents per sealed box.

Glossine--Oils and softens dry, brittle hair. Imparts a rich, healthy lustre. Indispensable for bobbed hair and unsurpassed in the opinion of social leaders and well-groomed gentlemen. 35 cents per long-lasting box.

These are but four of eighteen Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Preparations—As fine as money can buy

Questions for Image

- Have students use an online inflation calculator, such as this one from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, to estimate what the prices of Walker’s products would be like today. Were Madam C. J. Walker’s products affordable?

- What strategies does the advertisement use to sell the products? Mark the places in the text where the advertisement uses these different strategies.

- Find a present-day advertisement for a beauty product or products. The advertisement can be either print or digital. What strategies does this advertisement use to sell the product? How are its strategies similar to the strategies the Madam C. J. Walker advertisement uses? How are they different?

Once participants compare and contrast the two advertisements, have learners create their own advertisement for a product of their choice. What advertising strategies do they use?

Wrap-up:

-

What did you find most interesting or impactful about Madam C.J. Walker’s life and work?

-

What do you think has been left out of this story? What would you like to learn more about?

-

Can you think of something like Madam C.J. Walker’s life or business in your community?

-

How do you think Madam C.J. Walker felt at different points in her life? What is a time when you felt like that?

Tags

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- indiana

- indiana history

- women's history

- african american history

- labor history

- science

- gilded age

- early 20th century

- entrepreneur

- midwest

- african american women

- hour history lessons

- educational activity

- art and education

- women and the economy

- women and education

- women in science and technology

- women in the labor movement

- twhplp

- etc aah

Last updated: May 9, 2023