Last updated: October 28, 2020

Article

“As a Matter of Fact, I Presume I Shall Live to be President”: A Brief Biographical Sketch of Garfield’s Assassin

New York Public Library

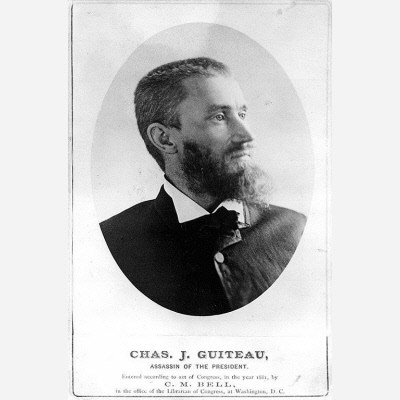

From the year he was born in Freeport, Illinois in 1841, Charles Julius Guiteau had lived a life of nearly constant instability. His mother died when he was just seven years old and his father was harsh and often negligent, and as a result he was usually looked after by his older sister Frances. According to Frances, he was very late in learning to speak and always seemed in constant, excited motion. However, Guiteau apparently strove for self-improvement and worked to educate himself. In 1859 he used an inheritance to attend the University of Michigan, but he was slow to make friends and left after a year to join a religious commune in Oneida, New York. He struggled to fit in with the community there as well and was described by most of his acquaintances as moody and egotistical.

This theme of instability in Guiteau’s life progressed and grew with time. He spent his adult years travelling from city to city, trying his hand at a variety of vocations and wild business schemes, but all ended in failure. One such idea was to start a theocratic newspaper in 1865, but the venture fell apart after three months. A few years later he tried the more direct approach of buying out a Chicago daily paper and reprinting New York Tribune articles. However, no one would loan him the money for his outlandish plan, despite a supposed promise to make one of his investors President of the United States if he would contribute.

Smithsonian-National Portrait Gallery

Nearly everyone who crossed paths with Guiteau noted his odd behavior, such as rapid mood swings and his habit of never looking someone in the eye while talking. Many family members and acquaintances believed him to be insane. His egotistical personality from his days at the Oneida Community seemed to intensify and his grandiose plans for himself continued unabated. Guiteau married a librarian named Annie Bunn in 1869, but after years of abuse and instability she divorced him in 1874. She would later recount Guiteau’s interest in the 1872 election and his hope that he would be appointed Minister to Chile if Horace Greeley won. He limped through a less-than-thorough examination for the Illinois bar (he was apparently asked three questions and got two correct, a score of 66%) but he rarely participated in trials, mostly working as a bill-collector. Guiteau ran into legal problems as a bill-collector, though, and spent brief stints in jail for scamming clients of their legal fees. He then tried the life of a traveling preacher for a few years in the late 1870s, where most in his audience struggled to make sense of his confused and disjointed speeches.

Guiteau finally believed he had discovered his purpose in early 1880 when he once again became interested in politics and the upcoming election. This time he attached himself to former President Ulysses S. Grant, Horace Greeley’s opponent in the 1872 election. He moved to New York City and tried to befriend the leaders of the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party, who supported Grant’s reelection. He even wrote a rambling, clichéd speech for the Republican frontrunner titled “Grant against Hancock”; when Garfield ended up with the nomination in June of 1880 Guiteau kept the speech largely the same and simply substituted Garfield’s name for Grant’s. After repeated requests, the Stalwarts allowed him to give his speech one time in front of about two dozen spectators. Despite his minimal audience, Guiteau claimed that it was his ideas that had won Garfield the presidency.

Convinced he had earned himself a prestigious appointment as a “personal tribute” for his work during the campaign, Guiteau was a regular presence in the White House reception room. He wrote to Garfield numerous times and once even received a brief audience with the President where he requested an appointment to the Paris consulship. But after months of waiting it eventually dawned on Guiteau that he would not receive the position he believed was owed to him. Shortly after this realization, he concluded that God wanted him to “remove the President for the good of the American people.” In support of his “revelation”, he recalled his numerous brushes with death, such as surviving a shipwreck and being thrown from a moving train, and he thus believed he had divine protection. Believing he would be viewed as a hero for saving the Republican Party from Garfield’s desire to reform civil service by ending the patronage system, Guiteau borrowed money from an old acquaintance (he was nearly penniless at this point) and purchased an ivory-handled pistol. He was sure that the ivory handle would look better should the pistol ever be put on display in a museum. Guiteau stalked the President for weeks before finally shooting Garfield at the Baltimore and Potomac train station in Washington D.C. on July 2, 1881.

University of Missouri-Kansas City, http://www.umkc.edu

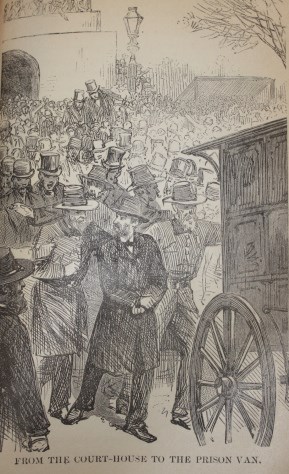

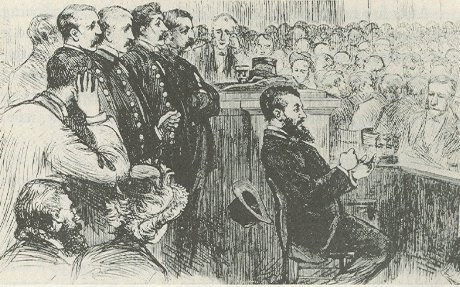

Guiteau’s trial began in November 1881, two months after Garfield’s death. Guiteau insisted that he had been temporarily insane and denied having any responsibility for his actions because, in his mind, he was merely the “appointed agent” of God’s will. Guiteau argued that “It was transitory mania that I had; that is all the insanity that I claim” and said that he never would have shot the President under his own free will. Guiteau also maintained that it was malpractice that had actually killed the President, stating “The doctors did that. I simply shot at him” and “…we acknowledge the shooting, but not the killing.” But while Guiteau claimed temporary insanity, his lawyers argued that he was entirely insane by pointing to testimonies from family and acquaintances regarding his long history of odd behavior. However, at the time the insanity defense relied on the M’Naghten rule, which held a defendant responsible if he knew his actions to be unlawful and understood the consequences; Guiteau was clearly aware of these two facts. The prosecution also maintained that even if Guiteau was insane he was still sane enough to know what he was doing and was thus accountable for his actions.

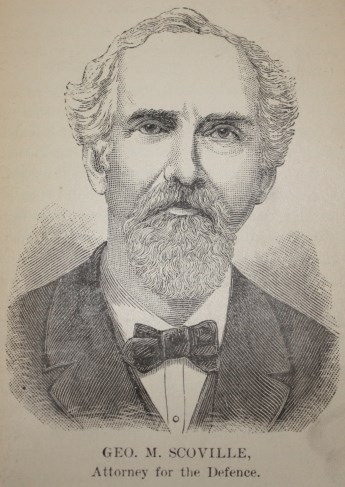

Even at the end of his trial, Guiteau clung to the belief that he was a hero. In a “Christmas Greeting” sent to newspapers Guiteau compared his patriotism to that of George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant and declared “As a matter of fact, I presume I shall live to be President.” In the trial he denied being a disappointed office-seeker and maintained that Garfield’s death was a political necessity, commanded by God, in order to unify the Republican Party and save the nation from a second civil war. His defense, which was lead for the most part by his brother-in-law George Scoville, tried to keep him quiet but Guiteau interrupted virtually every testimony with clarifications and insults (even taking numerous opportunities to insult his lawyer, Scoville, for his inexperience with criminal trials). The proceedings lasted nearly three months but after deliberating for just under an hour the jury found Guiteau guilty. He was hanged in Washington DC on June 30, 1882, just two days shy of a year after he shot President Garfield.