Last updated: March 30, 2023

Article

"The Greatest Dam in the World": Building Hoover Dam (Teaching with Historic Places)

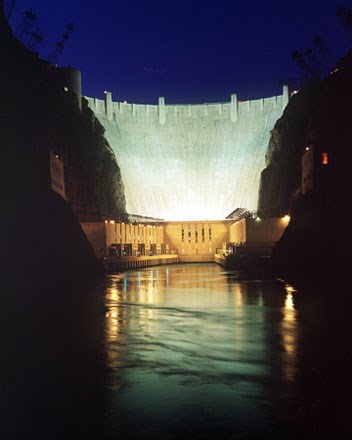

(Bureau of Reclamation; Andrew Pernick, photographer)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

Hoover Dam is as tall as a 60-story building. It was the highest dam in the world when it was completed in 1935. Its base is as thick as two football fields are long. Each spillway, designed to let floodwaters pass without harming the dam itself, can handle the volume of water that flows over Niagara Falls. The amount of concrete used in building it was enough to pave a road stretching from San Francisco to New York City.

The dam had to be big. It held back what was then, and still is, the largest man-made lake in the United States. The amount of water in the lake, when full, could cover the whole state of Connecticut ten feet deep. Only a huge dam could stand up to the pressure of so much water.

Building such a mammoth structure presented unprecedented challenges to the engineers of the Bureau of Reclamation. It stretched the abilities of its builders to the limits. It claimed the lives of 96 of the 21,000 men who worked on it.

Construction began in 1931. Americans began coming to see the big dam long before it was completed four years later. Most had to travel many miles, at the end through a hostile desert, to reach this location on the border between Nevada and Arizona. The builders soon constructed an observation platform on the canyon rim to keep the tourists away from the construction site.

Hoover Dam did, and continues to do, all the things its supporters hoped it would. It protects southern California and Arizona from the disastrous floods for which the Colorado had been famous. It provides water to irrigate farm fields. It supplies water and power to Los Angeles and other rapidly growing cities in the Southwest. But the dam also had an entirely unexpected result, one that began while it was still under construction. For millions of people in the 1930s, including those who would never visit it, Hoover Dam came to symbolize what American industry and American workers could do, even in the depths of the Great Depression. In the early 21st century, almost a million people still come to visit the huge dam every year.

About This Lesson

Hoover Dam, located where the Colorado River forms the boundary between the states of Nevada and Arizona, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is designated as a National Historic Landmark. This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places documentation, "Hoover Dam" (with photos); on National Historic Landmark documentation, "Hoover Dam" (with photos); and on Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) publications. The lesson was written by Marilyn Harper, historian, and edited by Teaching with Historic Places and Reclamation staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, government, and civics courses in units on the Great Depression and the New Deal, American political history, or the history of technology.

Time period: Early to mid 20th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

"The Greatest Dam in the World": Building Hoover Dam relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

-

Standard 1B—The student demonstrates how American life changed during the depression years.

-

Standard 2A—The student demonstrates understanding of the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

“The Greatest Dam in the World”:Â Building Hoover Dam relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

-

Standard C - The student uses appropriate resources, data sources, and geographic tools such as aerial photographs, satellite images, geographic information systems (GIS), map projections, and cartography to generate, manipulate, and interpret information such as atlases, data bases, grid systems, charts, graphs, and maps.

-

Standard E - The student locates and describes varying land forms and geographic features, such as mountains, plateaus, islands, rain forests, deserts, and oceans, and explains their relationships within the ecosystem.

-

Standard F - The student describes physical system changes such as seasons, climate and weather, and the water cycle and identifies geographic patterns associated with them.

-

Standard I - The student describes ways that historical events have been influenced by, and have influenced, physical and human geographic factors in local, regional, national, and global settings.

-

Standard J - observes and speculates about social and economic effects of environmental changes and crises resulting from phenomena such as floods, storms, and drought.

-

Standard K - The student proposes, compares, and evaluates alternative uses of land and resources in communities, regions, nations, and the world.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard B - The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

-

Standard C - The student describes the various forms institutions take and the interactions of people with institutions.

-

Standard F - The student describes the role of institutions in furthering both continuity and change.

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard B - The student describes the purpose of the government and how its powers are acquired, used, and justified.

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes the basic features of the political system in the United States, and identifies representative leaders from various levels and branches of government.

-

Standard G - The student describes and analyzes the role of technology in communications, transportation, information-processing, weapons development, and other areas as it contributes to or helps resolve conflicts.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

-

Standard D - The student describes a range of examples of the various institutions that make up economic systems such as households, business firms, banks, government agencies, labor unions, and corporations.

-

Standard I - The student uses economic concepts to help explain historical and current developments and issues in local, national, or global contexts

Theme VIII: Science, Technology, and Society

-

Standard B - The student shows through specific examples how science and technology have changed people's perceptions of the social and natural world, such as in their relationship to the land, animal life, family life, and economic needs, wants, and security.

-

Standard D - The student explains the need for laws and policies to govern scientific and technological applications, such as in the safety and well-being of workers and consumers and the regulation of utilities, radio, and television.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard C - The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues--recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard D - The student practices forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

-

Standard H - The student analyzes the effectiveness of selected public policies and citizen behaviors in realizing the stated ideals of a democratic republican form of government.

-

Standard I - The student explains the relationship between policy statements and action plans used to address issues of public concern.

Objectives for students

1) To list five factors that led to the construction of Hoover Dam.

2) To identify some of the work involved in the design and construction of the dam.

3) To explain the steps in the construction process and their dangers.

4) To identify some of the factors contributing to public perceptions of Hoover Dam and its construction.

5) To describe the impact Hoover Dam had on the Southwest and the nation and to explore some of its long-term implications.

6) To identify public works in their own local community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can be used directly on the computer or printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a small version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

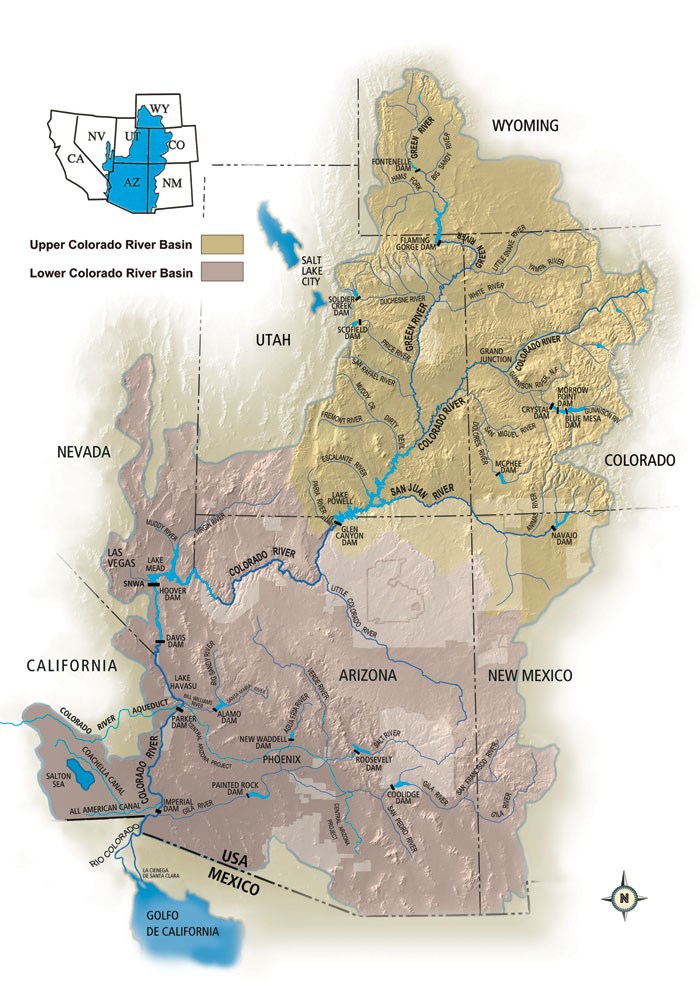

1) One map showing the Colorado River Basin;

2) One reading about the construction of Hoover Dam;

3) Two documents, a "Short Course in Engineering" and selections from President Roosevelt's speech at the dedication of Hoover Dam in 1935;

4) One illustration showing three views of Hoover Dam; and

5) Seven historic photos.

Visiting the site

Hoover Dam is located approximately 30 miles southeast of Las Vegas, on the Nevada-Arizona border. From Las Vegas, take US Highway 93 South and continue about 20 miles to Boulder City. In Boulder City, take a left at the second stoplight in town (there are only two of them). Continue on US 93 for about 5 miles to the turn-off to Nevada State Route 172—the Hoover Dam Access Road. Take NV SR 172 for about 2 miles to the dam. All vehicles are required to undergo a security inspection prior to visiting the dam. Tickets for tours of the dam and the power plant are available at the Visitor Center.

Tickets can also be purchased on-line. There is a charge for the tours, in addition to an admission charge for the Visitor Center. The Visitor Center is open every day of the year except for Thanksgiving and Christmas days. All visitors are required to go through security screening when entering the Visitor Center.

Access to the Visitor Center is most convenient from the parking garage on the Nevada side of the dam. There is a fee for parking. Oversized vehicles, recreational vehicles, and vehicles with trailers must use the parking lots on the Arizona side of the dam.

Check the Hoover Dam website for more detailed information, including seasonal hours of operation.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

(Bureau of Reclamation; Ben Glaha, photographer)

Setting the Stage

Congress passed the Reclamation Act in 1902, during the Progressive Era administration of President Theodore Roosevelt. One of the definitions of the word "reclamation" is "the recovery of a wasteland or of flooded land so it can be cultivated." ¹ The new legislation created a federal program to bring water to the desert lands of the West by constructing dams and reservoirs to store water for irrigation, as well as canals to deliver that water to farms. The goal was to encourage the growth of small family farms. The U.S. Reclamation Service, renamed the Bureau of Reclamation in 1923, was created to design and build these systems.² In 1924, Reclamation reported that 143,000 people lived on the agency's 24 irrigation projects and that farm earnings for that year totaled $70 million.

By this time, however, Reclamation's objective was changing and expanding. Where agency efforts had focused on building dams and irrigation systems to supply water to small farms, Reclamation was now envisioning vast projects that would cover whole river basins and use the water to do more than irrigate agricultural fields. These new projects would also control floods, supply water to growing cities, and generate electricity to fuel industrial growth in a new West.

The first of these great multipurpose projects would be a huge dam on the lower Colorado River.

¹ Wictionary website, accessed 1/30/2011.

² The name “Reclamation” will be used throughout this lesson to refer to both the U.S. Reclamation Service and the Bureau of Reclamation.

Locating the Site

Map 1: The Colorado River Basin

The geographic area drained by a river and its tributaries is called a "basin." The rivers and streams shown on this map all flow into the Colorado River. The canals and aqueduct in California receive water from the Colorado. This map shows only Reclamation's dams in the basin.

Questions for Map 1

1. Trace the course of the Colorado River. Where does it start? Where does it end? There are two places where the river forms the boundary between two states. Which states are they?

2. Trace the boundaries of the Colorado River Basin. Which states are within the Basin? Which are in the Upper Basin and which are in the Lower Basin?

3. Most of the water in the Colorado comes from melting snow in the Upper Colorado Basin. Most of the water is used in the Lower Colorado Basin. If you had to decide how much of the river's water each state could have, what factors might you consider? If the states did not agree with what you recommended, who do you think should have the right to make a final decision?

4. The river crosses the border into Mexico. How would you decide how much water Mexico could claim? Who could make that decision?

5. How many dams can you find on the Colorado River? Hoover Dam was the first of those on the map. Why do you think there are so many now?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Bureau of Reclamation and Hoover Dam

Before the building of Hoover Dam, the Colorado River was dangerous and unreliable. Melting snow in the mountains caused damaging floods during the late spring and early summer. Unpredictable flash floods could occur in any season. By mid-summer, the river’s flow was barely enough to supply the farms in southern California and Arizona that depended on it.

In 1905, the Colorado River flooded rich, irrigated farmland in the Imperial Valley in southern California. It caused enormous damage and permanently flooded thousands of acres. Over the next 20 years, Congress spent over $10 million trying to protect Imperial Valley farmers from floods.

Reclamation engineers began to study the Colorado River soon after passage of the Reclamation Act in 1902. They were looking for places to build dams to store the water from the annual spring runoff, releasing it gradually during the summer for irrigation. Initially the agency built some relatively small dams on the river’s tributaries. By the early 1920s, most people thought that building a big dam on the lower Colorado was the best way to store water to irrigate the low-lying valleys of Arizona and southern California and to protect them from floods. By this time, too, developers in Los Angeles and other rapidly growing cities in Southern California had added their powerful support for the project. They saw the dam as a potential source of water and hydroelectric power for homes, businesses, and factories.

In 1922, the seven states of the Colorado River Basin met to decide how to divide the waters of the river. Herbert Hoover, at that time the secretary of commerce for Republican President Calvin Coolidge, led the discussions. Most of the states were afraid California was going to get more than its fair share of the water. Ultimately, they managed to agree on a document, called the Colorado River Compact. The compact estimated that the river’s annual flow would be 16.5 million acre-feet, allocated 7.5 million acre-feet each to the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin, and set the amount of water each of the states in the Lower Basin would receive. The compact also committed the U.S. government to providing some of the water to Mexico. Some states were not happy about the compact; Arizona did not ratify it until 1944. It did permit planning for the dam to proceed, however.

Also in 1922, congressional representatives from California introduced a bill to authorize Reclamation to build the big dam on the lower Colorado. However, it took six more years before Congress passed the Boulder Canyon Project Act. The new law laid out four goals for the new dam: prevent floods, improve navigation on the river, store and deliver the Colorado’s waters, and generate electric power.

Reclamation’s engineers were looking forward to designing the huge dam. By this time, they were among the most knowledgeable and experienced dam builders in the world, but even they had never done anything this big. Hoover Dam would be the highest dam in the world, far taller than anything they had built so far. The lake it created would be the largest in the world.

The proposed dam would be so tall and the pressure of the water it held back so great that many people were worried. They weren’t sure that even Reclamation’s engineers had enough knowledge and experience to make the dam strong and safe. Others wondered whether the expected benefits would be enough to justify the enormous cost. Despite these questions, planning and design went forward.

In March 1931, Reclamation awarded the contract to build the dam to Six Companies, Inc. Six Companies was a group of some of the largest construction companies in the country. They joined specifically for this project. The contract divided the work between Six Companies and Reclamation. Reclamation engineers designed the dam and created the hundreds of detailed plans and specifications that the contractors would follow. They paid for all supplies and inspected the contractor’s work. If the work was consistent with the plans, they approved it for payment. Six Companies was responsible for converting Reclamation’s designs into actual concrete and steel. They hired and housed the workers. They transported supplies to the dam site. They were responsible for keeping the project on schedule and within budget.

The plan was for construction to start in the fall of 1931, in the depths of the Great Depression, which had begun with the stock market crash of 1929. Herbert Hoover, now president, wanted to start work on the dam earlier, probably as a way to ease high unemployment. Work actually began during the summer and continued around the clock until the dam was completed in 1935, two years ahead of schedule. By this time, Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, had been elected president.

The huge dam on the Colorado captured the imagination of journalists, authors, and filmmakers. It was conceived and launched under Republican administrations, but for many people it seemed to represent Roosevelt’s New Deal in action. The New Deal was famous for using public works projects to put Americans back to work. During a dark time, Hoover Dam seemed to transcend Americans’ fears about the future. In the early 21st century, almost a million visitors a year still come to see the great dam on the Colorado River.

Hoover Dam is 1,244 feet long at the top. It is 726 feet high from the lowest point of the foundation to the crest. The dam is 660 feet thick at the base and tapers to 45 feet thick at the top. Its reservoir was the largest artificial lake in the world for decades and is still the largest in the United States. The huge volume of water stored in the reservoir weighs so much that it deformed the earth’s crust, causing more than 600 small earthquakes in the late 1930s.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why did many people think something needed to be done to control the Colorado River? What sort of problems did the river create? What benefits would controlling it provide and to whom?

2. Why were congressional representatives from the state of California the leading supporters of a big dam on the Colorado?

3. Why do you think President Coolidge's secretary of commerce led the discussions leading up to the Colorado River Compact? What role might the federal government be able to play in making decisions like this?

4. An acre-foot is the volume of water that would cover one acre one foot deep. Why do you think they used a measure like that, rather than something like gallons? How many gallons of water are in an acre-foot? How much would that weigh?

5. Why do you think Reclamation’s engineers were excited about building the big dam? What were some of the concerns people had about its construction?

6. How did Reclamation and Six Companies divide the work on the dam?

Reading 1 is adapted from Joan Middleton, “Hoover Dam" (Mohave County, Arizona, and Clark County, Nevada) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1981); Joan Middleton and Laura Feller, “Hoover Dam" (Mohave County, Arizona, and Clark County, Nevada) National Historic Landmark documentation (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1985); William D. Rowley, The Bureau of Reclamation: Origins and Growth to 1945, Vol. 1 (Denver CO: Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2006); and Donald C. Jackson, “”Origins of Boulder/Hoover Dam: Siting, Design, and Hydroelectric Power,” in The Bureau of Reclamation : History Essays from the Centennial Symposium (Denver, CO: Bureau of Reclamation Department of the Interior, 2008), 273-288.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: A Short Course on Dam Building

In 1938, a New York publisher put out an illustrated “cartoon guide” for tourists visiting Hoover Dam, then known as Boulder Dam. The guide included the instructions excerpted below:

15 Minute Course in Engineering

Full (?) instructions on

HOW TO BUILD A DAM LIKE BOULDER

Complete with startling statistics

LESSON NO. 1

Take a canyon—Any canyon several blocks deep, with a good sized river running through it, will do. In fact there are still quite a few nice canyons along the Colorado River. You can take one of them—no one will miss it—maybe.

LESSON NO. 2

Preliminaries.—Before you can start on the dam, it will be necessary to build a town. You are going to have 3500 men working day and night for five years, so you’ve got to have some place to put ‘em.

And you will need to build some roads and erect a power line. At Boulder Dam they had to get the electricity from Los Angeles to build the dam which now sends electricity back to Los Angeles.

LESSON NO. 3

Materials.—The following list will give you most of what you need:

Cement—5 million barrels. That’s 16,667 freight cars full.

Sand and gravel—get quite a bit of this to mix with the cement; enough to make 4,440,000 cubic yards of concrete.

Ice plant—you’ve got to have a plant capable of turning out about 2 million pounds of ice a day.

Pipe for ice water—581 miles of it will do.

Plate steel for making pipes—88 million pounds—when you get into pipe 30 feet in diameter, you have to make your own.

Structural steel, nuts, bolts—and other stuff like that—18 million pounds.

Assorted steam shovels, etc.—you'll have to move about 6 million cubic yards of rock and dirt, digging tunnels and whittling out the canyon walls to make room for the dam.

LESSON NO. 4

Drying up the river.—It is necessary to have the spot where you intend to build your dam as dry as possible. To people who have not taken our engineering course, it seems pretty tough to dry out a river, but actually it’s a cinch. Simply drill four tunnels about ¾ miles through the cliffs above the water line. Make them each 56 feet in diameter, then line them with three feet of concrete. When you finish you will have 3 miles of tunnel 50 feet in diameter.

When you’ve got ‘em ready, dump a bunch of rock and dirt in the river, just below the upper end of the tunnels to block off the river. Make this “cofferdam” about a hundred feet high, two blocks thick at the base and 70 feet thick on top.

At the other end of the tunnels build another cofferdam to keep the water from backing up, pump the puddles out from between, and there you have it—a dry spot in the river, with the stream running right around it, through the tunnels. Simple?

LESSON NO. 5

Scaling—After standing out in the weather so long, canyon walls become soft and decayed on the surface. Before you can safely anchor a dam on ‘em, it will be necessary to scale off this unstable face. Lower several hundred men from the top on ropes and let them drill the cliffs full of holes. Stuff the holes with dynamite, and blast it away. Repeat as necessary.

LESSON NO. 6

Excavating.—Lower steam shovels into the canyon. (We forgot to say that you’ll have to string some cables and pulleys across the canyon to let stuff down to bottom. Better do that right now.) Build a platform so spectators can watch, and dig down about 130 feet from the river bed to bed rock, removing all loose material as you go. You are now ready to install the main portion of the dam.

LESSON NO. 7

Pouring the dam.—Take cement, rock and sand—mix well—add water—pour into canyon.

Concrete has a nasty habit of cracking. The lime in cement causes it to get hot when it is mixed with water. As it dries and cools, it shrinks and that’s what causes the cracks. Obviously you must not allow this to happen when you are building a dam. If cracks were to appear in your dam it might cause severe criticism from people living below the dam—or from their heirs.

It would take 150 years for all that concrete in the dam to cool under normal conditions. To hurry it up, string two or three miles of water pipe around through each five-foot layer of concrete as you pour it. From your ice plant, run ice cold brine through the pipes. This will cause the mass to cool and shrink quickly. You can then pump a very thin cement “soup” into cracks and spaces that have opened up. Your dam will be sealed tighter than a drum—and wedged between the canyon walls.

LESSON NO. 8

Spillways.—During your spare time you can erect a spillway on each side of the canyon, on the lake side of the dam. Drill holes connecting them with two of the tunnels constructed in Lesson 4. Plug the upper end of the tunnels to cut off water from the lake. At flood time, if the lake rises high enough to reach the spillways, it can be turned out through these original tunnels.

LESSON NO. 9

Intake towers and power house.—Build four intake towers on the upstream side of the dam, being sure that the top of ‘em is above the high water line. Erect a power house below the dam. Now drill holes through the cliffs from towers to power plant. Connect them with pipes. As you make each section of pipe, X-ray it for defects.

This completes our engineering course.

Questions for Reading 2

1. This guide contains many large numbers. Can you think of ways to translate those numbers into comparisons with more familiar things, so that it would be easier to get a sense of how big the project was?

2. The diversion tunnels were among the longest in the world when they were built. Six Companies thought that building them was the most critical part of the project. Under their contract with Reclamation, they would have to pay $3,000 for every day they exceeded the deadline for finishing this part of the work. Why do you think both Reclamation and Six Companies thought the diversion tunnels were so important? Do you agree? Explain your answer.

3. Why was it important to speed up the cooling process? How long would it take for the concrete in the dam to cool by itself? (The pipes are still there, buried in the concrete.)

4. The spillways at Hoover Dam are only used when the water in the reservoir is so high that it would otherwise overflow the top of the dam. Why do you think the engineers thought they had to keep this from happening?

5. In Lesson 1, the guide suggests, possibly not quite seriously, that you could take any canyon on the Colorado you wanted—"no one will miss it, maybe." There are many canyons on the river, some almost as dramatic as the Grand Canyon, located just upstream from Hoover Dam's reservoir. What might people "miss" about these canyons if they were filled with water? Do you think anybody today would suggest that no one might notice if you flooded one of them? Why or why not?

Reading 2 is abridged from Reg Manning's Cartoon Guide of the Boulder Dam Country (Locust Valley, NY: J.J. Augustin, 1938), pages 10-17. Used by permission.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Excerpts from President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Speech at the Dedication of Boulder Dam, Sept. 30, 1935

Roosevelt’s speech was front-page news in newspapers all over the country. In addition to the 10,000 people who braved 102o heat to hear the speech in person, it was broadcast to a radio audience of millions of people.

This morning I came, I saw and I was conquered, as everyone would be who sees for the first time this great feat of mankind.

We are here to celebrate the completion of the greatest dam in the world, rising 726 feet above the bedrock of the river and altering the geography of a whole region; we are here to see the creation of the largest artificial lake in the world—115 miles long, holding enough water, for example, to cover the State of Connecticut to a depth of ten feet; and we are here to see nearing completion a power house which will contain the largest generators yet installed in this country.

All these dimensions are superlative. They represent and embody the accumulated engineering knowledge and experience of centuries; and when we behold them it is fitting that we pay tribute to the genius of their designers. We recognize also the energy, resourcefulness and zeal of the builders, who, under the greatest physical obstacles, have pushed this work forward to completion two years in advance of the contract requirements. But especially, we express our gratitude to the thousands of workers who gave brain and brawn to this great work of construction.

We know that, as an unregulated river, the Colorado added little of value to the region this dam serves. When in flood the river was a threatening torrent. In the dry months of the year it shrank to a trickling stream. The gates of these great diversion tunnels were closed here at Boulder Dam last February. In June a great flood came down the river. It came roaring down the canyons of the Colorado, through Grand Canyon, Iceberg and Boulder Canyons, but it was caught and safely held behind Boulder Dam.

Across the San Jacinto Mountains southwest of Boulder Dam, the cities of Southern California are constructing an aqueduct to cost $220,000,000, which they have raised, for the purpose of carrying the regulated waters of the Colorado River to the Pacific Coast 259 miles away.

Across the desert and mountains to the west and south run great electric transmission lines by which factory motors, street and household lights and irrigation pumps will be operated in Southern Arizona and California.

Boulder Dam and the powerhouses together cost a total of $108,000,000. The price of Boulder Dam during the depression years provided [work] for 4,000 men, most of them heads of families, and many thousands more were enabled to earn a livelihood through manufacture of materials and machinery.

And this picture is true on different scales in regard to the thousands of projects undertaken by the Federal Government, by the States and by the counties and municipalities in recent years.

Throughout our national history we have had a great program of public improvements, and in these past two years all that we have done has been to accelerate that program. We know, too, that the reason for this speeding up was the need of giving relief to several million men and women whose earning capacity had been destroyed by the complexities and lack of thought of the economic system of the past generation.

In a little over two years this great national work has accomplished much. We have helped mankind by the works themselves and, at the same time, we have created the necessary purchasing power to throw in the clutch to start the wheels of what we call private industry. Such expenditures on all of these works, great and small, flow out to many beneficiaries; they revive other and more remote industries and businesses. Labor makes wealth. The use of materials makes wealth. To employ workers and materials when private employment has failed is to translate into great national possessions the energy that otherwise would be wasted. Boulder Dam is a splendid symbol of that principle. The mighty waters of the Colorado were running unused to the sea. Today we translate them into a great national possession.

Today marks the official completion and dedication of Boulder Dam. This is an engineering victory of the first order—another great achievement of American resourcefulness, American skill and determination.

That is why I have the right once more to congratulate you who have built Boulder Dam and on behalf of the Nation to say to you, "Well done."

Questions for Reading 3

1. During the 1920s, the big dam on the Colorado was usually called the "Boulder Canyon Project" or sometimes "Boulder Dam." In 1930, President Hoover's secretary of the interior named it "Hoover Dam." Roosevelt defeated Hoover in the presidential election of 1932. Why do you think he used the old name in his speech? (In 1947, Congress unanimously changed the name back to "Hoover Dam.")

2. What three groups did Roosevelt credit with the building of the dam? Which group's contributions do you think he valued the most? What makes you think so? Do you agree, based on what you know so far?

3. The President identified benefits the new dam had already provided. What were they? Whom did they benefit?

4. Roosevelt strongly defended the work relief projects for which his administration was famous. What arguments did he use? Do you think he made a good case? Why or why not?

5. If you were reading or listening to Roosevelt's speech in 1935, would you think that Hoover Dam was one of his New Deal work relief projects? Was it? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: Hoover Dam

(Bureau of Reclamation)

This image shows three views of the dam. The left side shows what a visitor looking upstream at the dam would actually see. The cut-away view on the right side shows features that would not be visible from the surface. Although not shown in the illustration, all of the features shown in the cut-away are duplicated on the other side of the dam. The cross section in the upper right hand corner is a side view.

Questions for Illustrations 1:

1. Look carefully at the cut-away view. Can you trace the course the water follows from the reservoir through the power plants and outlet works and then back into the river? How does that change if the level of the reservoir is getting too high?

2. How many of the features mentioned in Reading 2 can you find in this image? Is the image or the reading more useful in helping you understand Hoover Dam?

3. Reclamation engineers prepared hundreds of drawings for the construction company—all much more detailed than this simplified illustration. Why do you think the detailed drawings were necessary? How do you think the engineers decided where to locate the features shown here?

4. Look at the drawing in the upper right hand corner. Why do you think the dam had to be so thick at the bottom?

5. Find the penstocks that carry the water from the intake towers to the horseshoe-shaped powerhouse at the foot of the dam. One of the definitions of "penstock" is a pipe or conduit that carries water from a reservoir to electrical generating equipment. The Boulder Canyon Project Act said that the cost of building Hoover Dam had to be repaid by selling electricity and that contracts for all the electricity had to be signed before construction began. Why do you think that was required? When the contracts were signed, almost two thirds of the electricity went to Southern California. Why do you think that might have been the case?

Visual Evidence

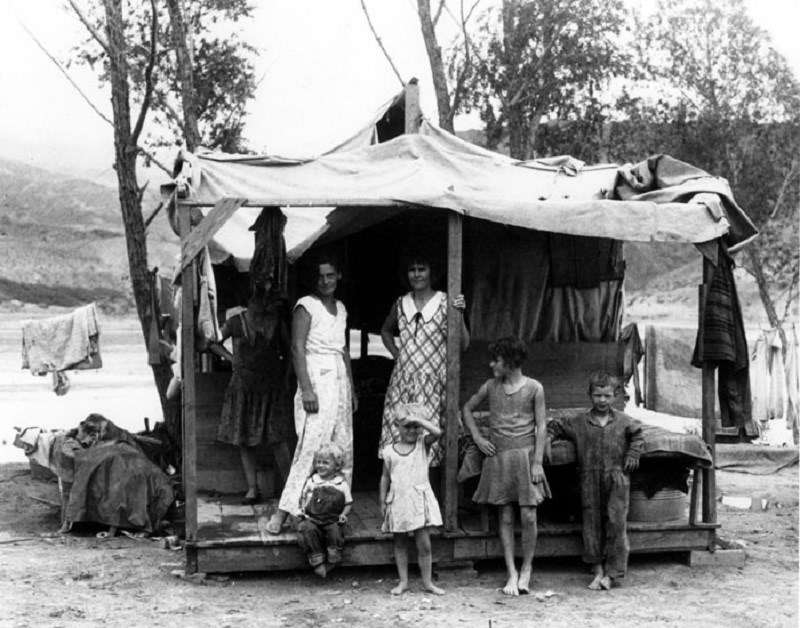

Photo 1: Men Seeking Work at Hoover Dam, August 1931

(Bureau of Reclamation; photographer unknown)

(Boulder City Museum and Historical Association; photographer unknown. Used by permission)

Questions for Photos 1 and 2:

1. How many men can you count in Photo 1? Why do you think so many people came to this remote and hostile location looking for work? What were conditions like in America in 1931? Refer to your textbook if necessary.

2. Describe the setting in these images. The average high temperature in this area in August is 103 degrees. Summer temperatures in the canyon can easily reach 125 degrees. The area is also prone to cloudbursts, high winds, and sudden floods. What do you think working here would be like? Do you think you would have come here looking for a job?

3. Many of the men seeking work brought their families with them. Why do you think they did that?

4. Work on the dam began sooner than originally planned. Housing for workers in the new town of Boulder City wasn't ready when these photos were taken. Families created a temporary community called "Ragtown." Why do you think it was called that?

5. Describe the shelter shown in Photo 2. Do you think this would have been adequate? The shelter seems to be located next to the river. Do you think that would have been a safe place to live? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 3: “High Scalers”

(Bureau of Reclamation; Ben Glaha, photographer)

Questions for Photo 3

1. Reread Lesson No. 5 in Reading 2. In addition to drilling holes for dynamite, the scalers also knocked unstable rock loose by hand. Why was this work necessary?

2. What safety equipment can you find in this picture? How much protection do you think it offered against rock falling down from above? Look at the upper right hand corner of the image. This shows the floor of the canyon, hundreds of feet below. Do you think the safety equipment would have kept the men from falling?

3. How many high scalers can you find in this photo? Other historic photos show dense rows of men working close together on the canyon walls. How safe do you think this would have been?

4. Many newspapers and magazines featured descriptions and images of the "high scalers." Why do you think they did that? Do you think you would have wanted to do work like this? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: "Drilling Jumbo"

(Bureau of Reclamation; Ben Glaha, photographer)

Six Companies came up with a number of new and ingenious ways to drill the four diversion tunnels more quickly, and one was the “drilling jumbo.” Eight of these jumbos were built, each mounted on the back of a 10-ton truck. The jumbos backed up to the working faces in the tunnels so that men using all the drills could work at the same time and higher on the wall without the need for scaffolds. The men filled the holes they had drilled with dynamite and then the jumbos drove away. After the dynamite was detonated, the rock dislodged by the explosion was taken out of the tunnel. Eventually they removed 1.5 million cubic yards of rock.

Questions for Photo 4

1. Look carefully at this image. Look for the drills (they look a little like machine guns). How many of them can you count?

2. Why do you think Six Companies developed this process? How do you think they might have done this work without the jumbos? Why do you think Six Companies was so anxious to get this part of the project done quickly? Refer to Reading 2 if necessary.

3. Internal combustion engines produce carbon monoxide. State laws prohibited using them in enclosed spaces like tunnels for health and safety reasons, but Six Companies used the jumbos anyway. What kind of danger does carbon monoxide present? Why do you think Six Companies disregarded the state law?

4. What other hazards do you think the men working on the jumbos might have faced?

5. How large is 1 cubic yard? Measure your classroom and figure out how many cubic yards it could hold. How many of your classrooms would it take to hold 1.5 million cubic yards?

Visual Evidence

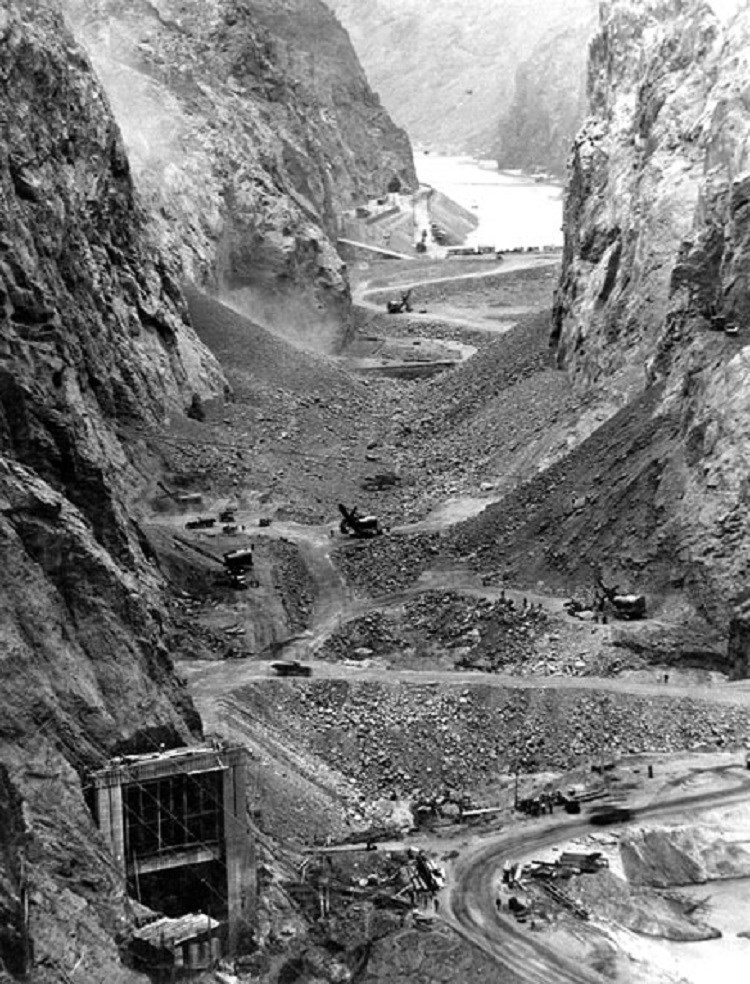

Photo 5: Work in the Canyon

Questions for Photo 5

1. What do you think is going on in this image? Where is the river? Look at Illustration 1. Does that help you figure out where the river went?

2. How many steam shovels can you count? Based on the size of the people in the image, how big do you think these shovels were?

3. Go back to Reading 2. How did the shovels get down into the canyon?

4. The shovels had to remove about 130 feet of soil and loose rock before they could get down to solid rock. Why do you think it was so important to do that before starting work on the dam structure itself?

5. By 1933, the date of this photo, Six Companies had built a lookout on the top of the canyon for tourists coming to the site. Why do you think visitors would drive so far to watch the dam under construction? Why do you think the construction company was willing to spend the money to build the lookout?

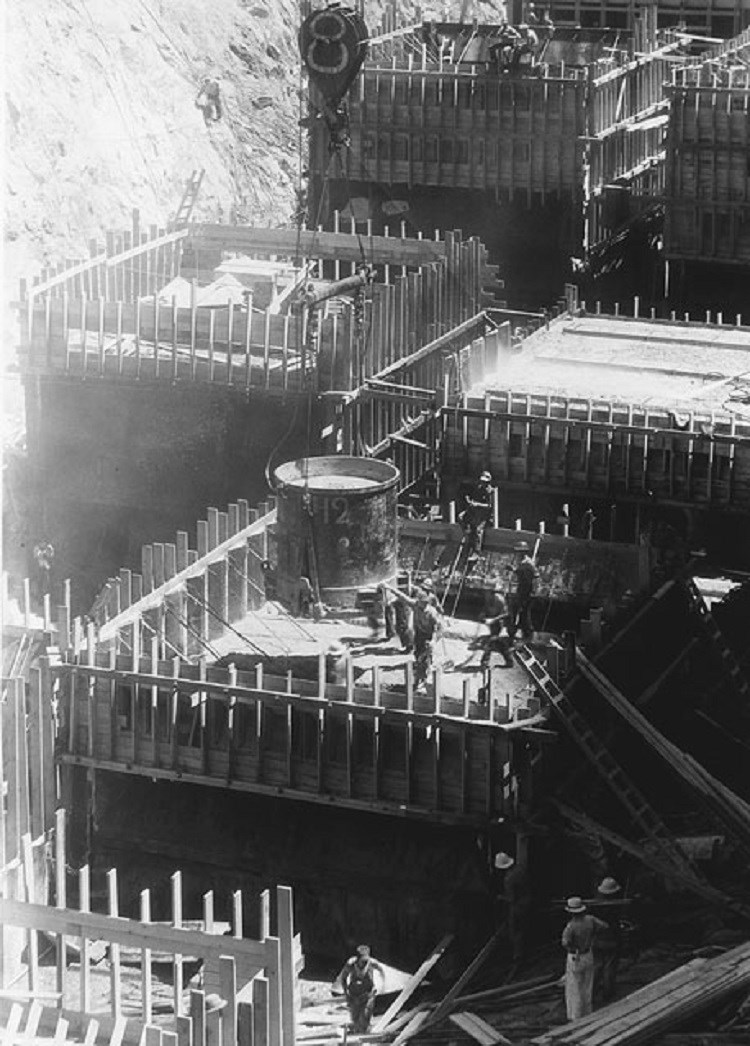

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Laying the Concrete for the Dam

(Bureau of Reclamation; Ben Glaha, photographer)

Putting It All Together

By studying "The Greatest Dam in the World": Building Hoover Dam, students have learned why Hoover Dam was a triumph for the engineers of the Bureau of Reclamation, for the construction company that built it, and for the thousands of men who worked to complete it. For many Americans, Hoover Dam also came to be a powerful symbol of what American industry and American workers could accomplish, even in the depths of the Great Depression. The following activities will help students build on what they have learned.

Activity 1: Which Job Would You Want?

Have students list as many kinds of work as they can based on the readings and the images. Ask them to consider all kinds of jobs. You couldn't build the dam without men to pour concrete. Could you build it without men to drive trucks or feed the workers? The Hoover dam website has a list of additional jobs. Then divide the class into small groups. Ask each group to select a job and do some research on it. Then ask them to imagine what it might have been like to have that job at Hoover Dam. What would have been the plusses? What would have been the minuses? Ask each group to make a short presentation to the class and then have the other students vote on what job would have been the hardest and why. Which job would have been the most dangerous? Which job would be most important? Finally, ask them to consider which job they themselves would like best.

Activity 2: "Seven Wonders of the United States"

In February 1942, a soldier stationed at a training camp in Louisiana wrote the following letter to the New York Times:

The Regimental Intelligence, Platoon of the 114th Infantry, Forty-Fourth Division, recently reviewed the merits of the Seven Wonders of the World. The discussion took a turn when we reminded ourselves that these wonders belonged to the ancient world. Right off we decided to prepare a list of seven wonders of the United States. Our choices were based on those which were obvious, from the list of the ancient world wonders, massive, man-made, and enduring. . . . The order is purely arbitrary. We submit: Empire State Building, Golden Gate Bridge, Boulder Dam, River Rouge plant, Pulaski Skyway, Rushmore Memorial, New York City Subway.

Signed:

Corporal Joe Ward ³

Divide the class into seven small groups. Ask the first group to identify and describe the original "Seven Wonders of the World." Ask each of the other groups to study one of the six "wonders" (excluding Hoover Dam) on Corporal Ward's list. Ask each group to report back to the class. In a whole class discussion, compare and contrast the ancient and modern wonders. Then ask the students to come up with their own list of "Wonders of the United States." Identify the characteristics places would have to have to be on such a list. Ask the students to identify as many places as they can that have those characteristics. Which of those would they select as their "Seven Wonders"? How would their list compare with the original "Seven Wonders of the World" and with Corporal Ward's "Seven Wonders of the United States? Would Hoover Dam be on their list?

Activity 3: Hoover Dam and the Arid West

Hoover Dam has accomplished every goal set forth in the Boulder Canyon Project legislation. It prevents disastrous floods. It stabilizes the flow of water in the river, improving boat navigation. It supplies water to irrigation projects in California and Arizona. Huge aqueducts carry water from the Colorado to Los Angeles and other cities in Southern California. The power plants provide electricity to Los Angeles, Phoenix, Las Vegas, and San Diego.

The availability of water stored behind Hoover Dam and the power produced by that water played a critical role in the growth of the American Southwest in the mid-20th century, but the demand for more water and electricity soon outstripped what this one dam could provide. Ask students to investigate how the places supplied by Hoover Dam have grown since 1935. They should be able to get population data for the states and cities listed above. Ask them to look up the construction dates for the other Colorado River dams shown on Map 1, as well as the purpose/benefits for which they were built. How do these dates relate to the growth statistics the students have collected?

Then ask the students to gather information on changes in the volume of water flowing down Colorado River during that period. How does that compare with the 16.5 million acre feet that the Colorado River Compact used as the basis for calculating the amount of water available for allocation to the states? That estimate has turned out to be too high, because the early 20th century was unusually wet while the period since then has been much drier. Then ask students to research the amount of water that the Colorado River Compact allocated to each state in the Lower Basin. Have students compare the data on the demand for water with the data on the available supply and then hold a whole class discussion brainstorming what problems might arise if the trends the students have identified continue.

Finally, ask the students to consider what effect building a new dam might have on these problems. What benefits would a new dam provide? What difficulties might those building it encounter? Ask them to compare and contrast these difficulties with the ones the builders of Hoover Dam faced. Do students think it would be necessary for the federal government to be involved to plan and complete such a new dam? Why or why not?

Activity 4: Public Works in the Local Community

Hoover Dam is an example of a "public works" project. According to Webster's Dictionary, "public works" are construction projects, such as water treatment plants, power plants, flood control systems, and highways and transportation networks that are built by the government for the public. They are critical to the functioning of modern communities, but few people notice them unless something goes wrong. Divide students into small groups and ask them to investigate examples of public works in their own community. They may be surprised at how old and how impressive some of these structures are. Private businesses may have built some of the dams, power plants, or other such facilities, but they do not fit the definition of "public works" given here. Ask the students to compare the private projects with the ones that were the result of government programs and to define for themselves the differences between public and private "works." How are they different? What might be the advantages of each type of ownership? Are there some kinds of works that only government can build?

Some of the public works in the community may be historic; students might want to consider nominating them to national or state registers of historic places or including them in walking or driving tours or in on-line travel itineraries for presentation to the local chamber of commerce. Others may be simply old.

Expanding demand and deferred maintenance may have affected their ability to do their jobs or to do them safely. Getting money in local budgets to keep them updated or even maintained is often difficult. If students identify a neglected public works project, they may want to consider creating a PowerPoint presentation to present to local government authorities to call attention to the problem.

³ “Our Own Seven Wonders,” Letters to the Editor, The New York Times, Feb. 6. 1942, 18; Historical New York Times Database, accessed 9/20/2011.

Supplementary Resources

In this lesson, students have learned why and how Hoover Dam was constructed. Those interested in learning more will find much useful information on the internet.

Hoover Dam Official Website

This website, maintained by the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Region, includes a wealth of information. In addition to directions and information about touring the dam, it includes links to “The Story of Hoover Dam,” a series of essays on construction of the dam, a database of hundreds of historic images, and a packet of educational materials.

Bureau of Reclamation History

This website includes links to a number of documents, including a short history of Reclamation, a longer, book-length history of the years before 1945, and a study of large Federal dams, including Hoover.

“Hoover Dam” PBS Film

This PBS production provides materials for teachers, in addition to a history of the dam and some of the people involved in its creation.

The Story of Hoover Dam Film

This website, provided by the National Archives and Records Administration, features a 1981 film that combines three short films dating from earlier periods. It includes historic footage of Hoover Dam under construction, including the high scalers in action and the concrete being poured into the forms. It also includes images showing the installation of the last turbine in the power plant and the benefits provided by the dam.

The Boulder City/Hoover Dam Museum

This website features images and other information focusing on the people who built Hoover Dam and who lived in Boulder City.

“Building Big”

This PBS miniseries, hosted by author David Macaulay, describes the engineering challenges encountered in building large dams, bridges, domes, skyscrapers, and tunnels in clear, easily understood, and kid-friendly terms and visuals. Hoover Dam is one of its “Wonders of the World.” The website also includes an educators' guide,” with hands-on activities.

Tags

- hoover dam

- water management

- farming

- irrigation

- bureau of reclamation

- nevada

- nevada history

- labor

- workers

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- labor history

- science

- early 20th century

- president roosevelt

- franklin d. roosevelt

- franklin delano roosevelt

- lake mead

- science and technology

- laborers

- arizona

- arizona history

- colorado river

- boulder city history

- twhplp