Last updated: July 31, 2023

Article

"The Great Chief Justice" at Home (Teaching with Historic Places)

(Courtesy of Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

John Marshall led the Supreme Court of the United States from obscurity and weakness to prominence and power during his 34 years in office, from 1801 to 1835. More than half his time as chief justice was spent at home in Richmond, Virginia. Marshall’s public duties in Washington, D.C., and on circuit in Virginia and North Carolina, consumed an average of less than six months a year. So he was often with family and friends at his two-and-a-half-story brick house, built between 1788 and 1790. Located at the corner of Ninth and Marshall Streets in downtown Richmond, this house stands as a permanent memorial to the Marshall family. No other site, not even the Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C., is so closely connected to "The Great Chief Justice."

John Marshall’s public and private roles were intertwined at home. He developed legal opinions, wrote public papers, and greeted famous guests at this place, where he also was a father, husband, and household manager. Today visitors to the John Marshall House can see evidence of both the public and private parts of his life at home. A striking symbol of his public life--a large judicial robe once worn by Marshall as chief justice--is displayed in the visitors’ Orientation Room, as is a small locket that was worn by Marshall’s wife, Mary Willis Ambler, whom he called "my dearest Polly." These two objects represent the public and private domains of a great man’s life, his career and family.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file "John Marshall House" (with photographs) and information from the John Marshall Foundation of Richmond, Virginia, and the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. It was written by John J. Patrick, a professor of education at Indiana University, where he is also director of the Social Studies Development Center and director of the ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brin gs the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in units on the Marshall Court during the Early National Period.

Time period: Late 18th century to mid-19th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

"The Great Chief Justice" at Home relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

-

Standard 3C- The student understands the development of the Supreme Court's power and its significance from 1789 to 1820.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

"The Great Chief Justice" at Home relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding that different scholars may describe the same event or situation in different ways but must provide reasons or evidence for their views.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard B - The student describes the purpose of government and how its powers are acquired, used, and justified.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes the basic features of the political systems in the United States, and identifies representative leaders from various levels and branches of government.

Theme X: Civic Ideals, and Practices

-

Standard A - The student examines the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

-

Standard C - The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues - recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard D - The student practices forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

Objectives for students

1) To describe the John Marshall House and the Marshall family's way of life there;

2) To identify the civic virtues and personal values that motivated John Marshall, and explain how they influenced his public and private actions and decisions.

3) To examine how the public and private sides of John Marshall's life and personality were related and integrated.

4) To identify and explain Marshall's core principles of constitutional government in his career as chief justice of the Supreme Court.

5) To investigate persons of historical significance in their own community and the historic sites that commemorate notable deeds and lives.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

1) Two maps showing the Chesapeake Bay region and Richmond;

2) Four readings drawn from biographies and papers of John Marshall emphasizing the virtues underlying John Marshall's commitment to his public and private duties;

3) Five photographs of the exterior and interior of the John Marshall House.

Visiting the site

The John Marshall House is maintained and operated by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA). Admission is charged and tours are provided. Reservations for tours must be made at least 24 hours in advance. The house is located at the corner of Ninth and Marshall Streets in Richmond, Virginia. For more information, write to the John Marshall House, 818 East Marshall Street, Richmond, VA 23219. You may also want to contact the John Marshall Foundation, 701 E. Franklin Street, Suite 1515, Richmond, VA 23219.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What style architecure do you think this building is? What purpose do you think the building serves?

Setting the Stage

During the eight-year administration of President George Washington (1789-1797), rival political parties formed to contest the policies and development of the federal government launched under the Constitution of the United States. One party, the Democratic-Republicans, was led by Thomas Jefferson. The other party, the Federalists, was led by Alexander Hamilton.

The Jeffersonian Republicans, as they often were called, stood for a strict construction or interpretation of the Constitution, which would limit the federal government to the powers specifically granted to it. They tended to oppose expansion of federal government power at the expense of the powers and rights of the state governments. By contrast the Federalist party of Hamilton favored a loose or broad construction of the Constitution, which would allow the expansion of federal government power to meet important needs of national scope.

John Marshall, a successful lawyer and local political leader in Virginia, was a staunch supporter of the new federal government. In 1801 he was appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court by the outgoing Federalist president, John Adams. During Marshall’s 34 years as chief justice, he transformed the Supreme Court into a powerful and revered institution. He wrote and presided over many Supreme Court decisions that used broad interpretation of the Constitution to support the federal government’s power in its relationship to the states of the federal union. Some of the Marshall Court’s decisions infuriated his cousin Thomas Jefferson, who served as president of the United States from 1801-1809.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Important roads of the Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay region.

Despite John Marshall's active political career, he spent much of his time with his wife, Polly, and their children at the home he had built in Richmond, Virginia, in 1790.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate the cities of Richmond and Washington, D.C. Calculate the distance from Richmond, the site of John Marshall's house, to Washington, D.C., the site of the Supreme Court.

2. How do you think Marshall traveled between these two places? Considering the means of travel used by people today, make a rough comparison of the time it would have taken then and now.

Locating the Site

Map 2: John Marshall House

and surrounding area, Richmond, Virginia.

Questions for Map 2

1. Locate the John Marshall House, the State Capitol Building, and the old City Hall.

2. Why do you think Marshall built his house on a site close to important state and municipal buildings?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: John Marshall at Home

In 1790 John Marshall and his wife, Mary Willis Ambler (he called her Polly), moved into their newly constructed house on lot 786 in the Shockoe Hill area (also called Court End) of Richmond, Virginia. He was 35 years old, a successful lawyer and representative of Henrico County to the Virginia legislature. She was 24, a mother of four children, one of whom had died shortly after birth, and a trustworthy adviser to John. The house was both a domicile and place of work.

The Marshall house was located a short distance from the courthouse and other public buildings, which attracted lawyers and public officials to the neighborhood. Spencer Roane, who became chief judge of the Virginia Court of Appeals, lived nearby. Roane’s house was separated from Marshall’s by a gully, an appropriate symbol of the political differences that marked their careers. Roane, a fervent Jeffersonian Republican, was a staunch public opponent of Marshall. Marshall’s Federalist principles were in strong opposition to the political party of Thomas Jefferson.

Many of Marshall’s political allies also lived in his neighborhood, and some were invited regularly to monthly dinners at his house. These "lawyers’ dinners" included about 30 prominent men seated around the table in the large dining room or great hall at the center of the first floor. No women were invited to these dinners, which lasted from mid-afternoon until late evening. Marshall’s slaves prepared the food and served the guests. According to city tax records, Marshall owned 10 adult slaves in 1791.

Guests at the Marshall house, particularly the ones invited to the lawyers’ dinners, usually discussed current public affairs and political issues. John Marshall’s cousin and rival, Thomas Jefferson, was often the object of sharp criticism, as were his Republican party followers. The talk was spiced occasionally, however, with spirited support for the other side by George Hay, a regular invitee to the lawyers’ dinners and an advocate of Jefferson’s political ideas. One ongoing constitutional issue was about the nature of Federalism and the division of power between the national government and the states. George Hay, Spencer Roane, and other Jeffersonians argued for states’ powers and rights in relationship to the central government. By contrast, John Marshall and his Federalist party associates argued the cause of nationalism and far-reaching supremacy of the federal government over the states.

The Jeffersonian Republicans and Federalists also argued about the nature of popular or free government. Marshall feared a tyranny of the majority and urged the rule of a higher constitutional law to limit the democratic power of the people’s representatives in Congress and the state legislatures. By contrast, Jefferson had a more optimistic view of majority rule and dismissed as elitist nonsense the Federalists’ fears of democratic despotism against unpopular individuals or minorities.

During the 1790s John Marshall became more and more involved in national politics. His pro-Federalist views were sharpened and deepened during this period when he spent much of his time at home. President John Adams in 1797 named him a special envoy to France, with Elbridge Gerry and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, to negotiate a serious international dispute between the U.S. and France known as the "XYZ Affair." In 1799 he won election from his congressional district in Virginia to the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1800 President Adams appointed Marshall secretary of state. In 1801 President Adams appointed Marshall to be chief justice of the Supreme Court, and the Senate confirmed this nomination unanimously. Marshall wrote to the president, "I hope never to give you occasion to regret having made this appointment." In the years ahead, only Jefferson and his followers had any regrets, as they fumed about the chief justice’s nationalistic opinions in landmark Supreme Court cases.

Marshall served as chief justice from 1801 until his death in 1835. His duties for the Court, however, left ample opportunity for Marshall to be at home. He usually spent less than six months each year in Washington, D.C., or traveling around the country "on circuit" to hear cases. For more than half his time he was in Richmond, where he paid close attention to both his family and his legal work. A notable example of the connections at home between his public and private interests occurred in 1819, when Marshall returned to Richmond in mid-March after presenting the Supreme Court’s opinion only a few days earlier in McCulloch v. Maryland.

Almost immediately after Marshall’s return home, he heard attacks on the Court’s decision from the Jeffersonian Republicans of Richmond. These advocates of states’ rights and powers felt thwarted by the nationalistic decision in the McCulloch case. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned as unconstitutional a law of the state of Maryland, which had been enacted to tax the National Bank of the United States. This decision to uphold the doctrine of implied powers expanded the scope of federal power.

A series of newspaper articles in the Richmond Enquirer strongly denounced Marshall, the Court, and the decision. A leader of the attacks on Marshall was Spencer Roane. Marshall suspected that Roane was the author of several critical articles in the Richmond Enquirer with the byline "Hampden." Marshall decided that he could not ignore the attacks against the Supreme Court and his constitutional principles. So he responded in writing to "Hampden" (Roane). Marshall’s articles in defense of his Supreme Court opinion in McCulloch v. Maryland were written at home and published in the Alexandria Gazette from June 30-July 15, 1819. These articles were signed "A Friend of the Constitution" to preserve the anonymity of the author. An excerpt from Marshall’s July 15 article shows his strong convictions about the value of the federal judicial department and its duty to uphold the Constitution and the rule of law.

The government of the Union was created by, and for, the people of the United States. It has a department in which is vested its whole legislative power, and a department in which is vested its whole judicial power. These departments are filled by citizens of the several states.

The propriety and power of making any law which is proposed must be discussed in the legislature before it is enacted. If any person to whom the law may apply, contests its validity, the case is brought before the court. The power of Congress to pass the law is drawn into question....

To whom more safely than to the judges are judicial questions to be referred? They are selected from the great body of the people for the purpose of deciding them. To secure impartiality, they are made perfectly independent. They have no personal interest in aggrandizing the legislative power. Their paramount interest is the public prosperity, in which is involved their own and that of their family.--No tribunal can be less liable to be swayed by unworthy motives from a conscientious performance of duty. It is not then the party sitting in his own cause. It is the application to individuals by one department of the acts of another department of the government. The people are the authors of all; the departments are their agents; and if the judge be personally disinterested, he is as exempt from any political interest that might influence his opinion, as imperfect human institutions can make him.

Marshall’s spirited defense of his Supreme Court decision in the McCulloch case demonstrates one way in which he brought his public life into his private home. Whether in Washington, D.C., or in Richmond, John Marshall could not disengage from the public duties and commitments to his vision of the U.S. Constitution.

Questions for Reading 1

1. What were the "lawyers’ dinners" that Marshall conducted at his home? What was the political significance of these dinners?

2. Why did Marshall in 1819 write essays, signed with a pseudonym, for publication in newspapers of Virginia and elsewhere?

3. What civic virtues and commitments to constitutional principles did Marshall exhibit in his authorship of his newspaper articles?

4. Read John Marshall's article again. Who appoints Supreme Court judges? Do you feel that Supreme Court judges are impartial parties able to make unbiased decisions for the "people"? Why or why not?

Reading 1 was compiled from Leonard Baker, John Marshall: A Life in Law (New York: Macmillan, 1974), 180-189; "Mister Chief Justice," a video program produced by the John Marshall Foundation of Richmond, Virginia, 1992; brochures of the John Marshall Foundation, Richmond, Virginia; and Gerald Gunther, ed., John Marshall’s Defense of McCulloch v. Maryland (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1969), 211-212.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: A Black Robe--Symbol of Civic Virtue and Constitutional Principles

John Marshall’s black robe, worn during his service as chief justice of the Supreme Court (1801-1835), is displayed today at the John Marshall House in Richmond, Virginia. It is a symbol of Marshall’s tenure on the Supreme Court.

President John Adams appointed Marshall to be chief justice in 1801 as one of his final actions before leaving office. Adams’ first choice for the job had been John Jay, who previously had served as the first chief justice. Jay, however, declined because in his view, widely shared at the time, the Supreme Court was too weak and unimportant; he said that he would not be head of "a system so defective." So John Marshall took the job and transformed it into the most powerful and prominent judicial position in the world.

Marshall brought unity and order to the Court by practically ending seriatim opinions (the writing of opinions by various justices). He influenced the Court’s majority to speak with one voice, through one opinion for the Court on each case before it. Of course, members of the Court occasionally wrote concurring or dissenting opinions, as they do today.

Often the Court’s voice was John Marshall’s. During his 34 years on the Court, the longest tenure of any chief justice, Marshall wrote 519 of the 1,100 opinions issued during that period, and he dissented only eight times. Chief Justice Marshall’s greatest opinions were masterworks of legal reasoning and graceful writing. They stand today as an authoritative commentary on the core principles of the U.S. Constitution.

Marshall’s first great decision came in Marbury v. Madison (1803), in which he ruled that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was void because it violated Article 3 of the Constitution. In this opinion, Marshall made a compelling argument for judicial review, the Court’s power to decide whether an act of Congress violates the Constitution. If it does, Marshall wrote, then the legislative act contrary to the Constitution is unconstitutional, or illegal, and cannot be enforced. Marshall wrote, "It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.... So if a law be in opposition to the Constitution...the Constitution and not such ordinary Act, must govern the case to which they both apply."

In a series of significant decisions, Marshall also established, beyond legal challenge, the Court’s power of judicial review over acts of state government. In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and Cohens v. Virginia (1821), Marshall wrote for the Court that acts of state government in violation of federal statutes or the federal Constitution were unconstitutional or void.

The Marshall Court’s decisions also defended the sanctity of contracts and private property rights against would-be violators in the cases of Fletcher v. Peck and Dartmouth College v. Woodward. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), Marshall broadly interpreted Congress’ power to regulate commerce (Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution) and prohibited states from passing laws to interfere with the flow of goods and transportation across state lines.

Chief Justice Marshall’s greatest opinions protected private property rights as a foundation of individual liberty. They also rejected claims of state sovereignty in favor of a federal Constitution based on the sovereignty of the people of the United States acting through a strong central government. Finally, Marshall clearly and convincingly argued for the Constitution as a permanent supreme law that the Supreme Court was established to interpret and defend. "Ours is a Constitution," Marshall wrote in 1819 (McCulloch v. Maryland), "intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs."

According to Marshall, only through broad construction of the federal government’s powers could the Constitution of 1787 be adapted to meet changing times. And only through strict limits on excessive use of the government’s powers could the Constitution endure as a guardian of individual rights. The special duty of the Supreme Court was to make the difficult judgments, based on the Constitution, about when to impose limits or to permit broad exercise of the federal government’s powers.

In 1833, near the end of John Marshall’s career, his associate on the Supreme Court, Justice Joseph Story, wrote a "Dedication to John Marshall" that included these words of high praise: "Your expositions of constitutional law...constitute a monument of fame far beyond the ordinary memorials of political or military glory. They are destined to enlighten, instruct and convince future generations; and can scarcely perish but with the memory of the Constitution itself." And so it has been, from Marshall’s time until our own, that his judgments and commentaries on the Constitution have instructed and inspired Americans.

Questions for Reading 2

1. What civic virtues did John Marshall exhibit during his 34 years as chief justice of the Supreme Court?

2. What are the main constitutional principles that Marshall upheld as chief justice? What examples or cases can be cited to show his commitment to certain constitutional principles?

3. How did Marshall transform the role and image of the Supreme Court during his tenure as chief justice?

Reading 2 was compiled and adapted from John J. Patrick, The Young Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 194-195.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: A Locket and a Strand of Hair--Symbols of Love and Family

Throughout nearly 49 years of marriage to John Marshall, Mary Willis Ambler (Polly) wore around her neck a locket with a strand of her hair inside. This locket is displayed today at the John Marshall House in Richmond, Virginia. It is an enduring symbol of the romantic love and family commitment shared by Polly and John.

It began on the day John Marshall asked Polly to marry him, when he was 27 years old and she was 16. Polly had admired him, even dreamed of marrying him, ever since she met Marshall two years before. But at this decisive moment, she said "No!" John was distressed and quickly left her house.

Polly was distraught and wept hysterically. She had really wanted to say "Yes!" But now it was too late, or so she thought. But her cousin, John Ambler, had witnessed the scene and acted suddenly to correct Polly’s mistake. He cut off a lock of her hair and went after John Marshall.

When Ambler caught up with Marshall, he gave him the strand of Polly’s hair, which Marshall thought she had sent to him. So he immediately went back to her house and proposed marriage once again. This time, Polly said "Yes!"

Polly and John were married on January 3, 1783, in the home of her cousin, John Ambler. Polly put into a locket around her neck the strand of hair that had brought John Marshall back to her. She may also have placed a strand of John Marshall’s hair in this locket, which stayed around her neck during every day of her marriage.

Polly and John had 10 children. Only six survived to adulthood. Three died in infancy and one died during early childhood. The tragedies of her children’s deaths weakened Polly, who became sickly and reclusive. During the last 25 years of her life, she usually stayed at home, often in the master bedroom. Her frailty and illness, however, did not diminish the deep love she and John had for each other.

On the morning of her death, December 25, 1831, Polly tried to remove the locket from around her neck. She was so weak that John had to help her. She wanted to see him put the keepsake around his neck, which John did. The locket, with her hair inside it, stayed around John’s neck until he died four years later in Philadelphia at the age of 79. His body was returned to Richmond and buried next to Polly in the Shockoe Hill Cemetery near his house. The locket was kept by one of Marshall’s children and eventually returned to the John Marshall House, where it is today.

John Marshall’s feelings about his life and marriage, his priorities and values, are clearly indicated by his epitaph. It was engraved on his tombstone exactly as he had wished. So how did this great man--this famous public figure and hero--wish to be remembered? This is what is written at the grave site:

John Marshall

Son of Thomas and Mary Marshall

was born the 24th of September 1755

Intermarried with Mary Willis Ambler

the 3rd of January 1783

Departed this life

the 6th day of July 1835

This marker stands today at the Shockoe Hill Cemetery, an enduring testimonial about what ultimately was most important to the man others called "The Great Chief Justice."

Questions for Reading 3

1. Why did Polly Marshall always wear a locket containing a strand of her hair? Why did John Marshall wear this locket from December 25, 1831, until July 6, 1835?

2. What personal values of the Marshall family are symbolized by Polly’s locket and the use of it by Polly and John?

3. What does the epitaph on John Marshall’s gravestone reveal about his personal values? What does the epitaph suggest about his priorities? Do you think the public side of his life was more or less important to him than the private side?

Reading 3 was compiled from Leonard Baker, John Marshall: A Life in Law (New York: Macmillan, 1974), 72-73 and 769-770; and "Mister Chief Justice," a video program produced by the John Marshall Foundation of Richmond, Virginia, 1992.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: John Marshall on "My Dearest Polly"

John’s last written statement for and about Polly was penned at his home on December 25, 1832, exactly one year after her death. It reveals much about the deep feelings the chief justice had for his "Dearest Polly."

This day of joy & festivity to the whole Christian world is to my sad heart the anniversary of the keenest affliction which humanity can sustain. While all around is gladness my mind dwells on the silent tomb, & cherishes the remembrance of the beloved object which it contains. On the 25th of December 1831 it was the will of Heaven to take to itself the companion who had sweetened the choicest part of my life, had rendered toil a pleasure, had partaken of all my feelings & was enthroned in the inmost recesses of my heart. Never can I cease to feel the loss & to deplore it. Grief for her is too sacred ever to be profaned on this day, which shall be during my existence devoted to her memory.

On the 3rd of January 1783 I was united by the holiest bonds to the woman I adored. From the hour of our union to that of our separation I never ceased to thank Heaven for this its best gift. Not a moment passed in which I did not consider her as a blessing from which the chief happiness of my life was derived. This never dying sentiment, originating in love, was cherished by a long & close observation of as amiable & estimable qualities as ever adorned the female bosom.

To a person which, in youth, was very attractive, to manners uncommonly pleasing, she added a fine understanding & the sweetest temper which can accompany a just & modest sense of what was due herself.

I saw her first the week she attained the age of fourteen & was greatly pleased with her. Girls then came into company much earlier than at present. As my attentions, though without any avowed purpose, nor so open nor direct as to alarm, soon became ardent & assiduous her heart received an impression which could never be effaced. Having felt no prior attachment, she became, at sixteen, a most devoted wife. All my faults, and they were too many, could never weaken this sentiment. It formed a part of her existence. Her judgement was so sound & so safe that I have often relied upon it in situations of some perplexity. I do not recall ever to have regretted the adoption of her opinion. I have sometimes regretted its rejection. From native timidity she was opposed to everything adventurous, yet few females possessed more real firmness. That timidity so influenced her manners, that I could rarely prevail on her to display in company the talents I knew her to possess. They were reserved for her husband, & her select friends. Though serious as well as gentle in her deportment, she possessed a good deal of chaste, delicate & playful wit, and, if she permitted herself to indulge this talent, told her little story with grace, & could mimic very successfully the peculiarities of the person who was the subject. She had a fine taste for belle lettre reading, which was judiciously applied in the selection of pieces which she admired. This quality by improving her talents for conversation contributed not inconsiderably, to make her a most desirable & agreeable companion. It beguiled many of those winter evenings during which her protracted ill health & her feeble nervous system, confined us entirely to each other. I can never cease to look back on them with deep interest and regret. Time has not diminished & will not diminish this interest or this regret. In all the relations of life she was a model which those to whom it was given, cannot imitate too closely. As the wife, the mother, the mistress of a family & the friend, her life furnishes an example to those who could observe it intimately which will never be forgotten. She felt deeply the distresses of others & indulged the feeling liberally on objects she believed to be meritorious.

She was educated with a profound reverence for religion which she preserved to her last moment. This sentiment among her earliest & deepest impressions, gave a color to her whole life. Hers was the religion taught by the Savior of man. Cheerful, mild, benevolent, serious, humane, intent on self improvement & the improvement of those who looked to her for precept or example. She was a firm believer in the faith inculcated by the church in which she was bred, but her soft & gentle temper was incapable of adopting the gloomy & austere dogmas which some of its professors have sought to engraft on it. I have lost her! And with her I have lost the solace of my life! Yet she remains still the companion of my retired hours,--still occupies my inmost bosom. When I am lone and unemployed, my mind unceasingly turns to her. More than a thousand times since the 25th of December 1831, have I repeated to myself the beautiful lines written by Gen. Burgoyne under a similar affliction, substituting Mary for Anna.

Encompassed in an angel’s frame,

An angel’s virtues lay;

Too soon did Heaven assert its claim

And take its own away.

My Mary’s worth, my Mary’s charms

Can never more return.

What now shall fill these widowed arms?

Ah, me! My Mary’s urn!

Ah, me! Ah, me! My Mary’s urn!!!

Questions for Reading 4

1. What aspects of his relationship with Polly did John recall in this document?

2. What characteristics of Polly’s personality were revealed by John in this document?

3. What qualities or virtues of Polly were most valued by John?

4. What impressions of Polly do you derive from this letter? What is suggested about her strengths or weaknesses?

5. What qualities of John Marshall are evident in his essay about his wife?

Reading 4 was compiled from the collection of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities at the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

Visual Evidence

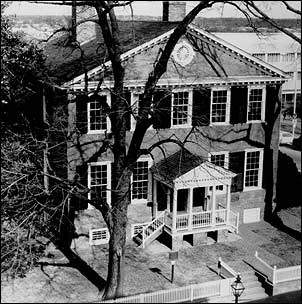

Photo 1: Exterior front view, John Marshall House.

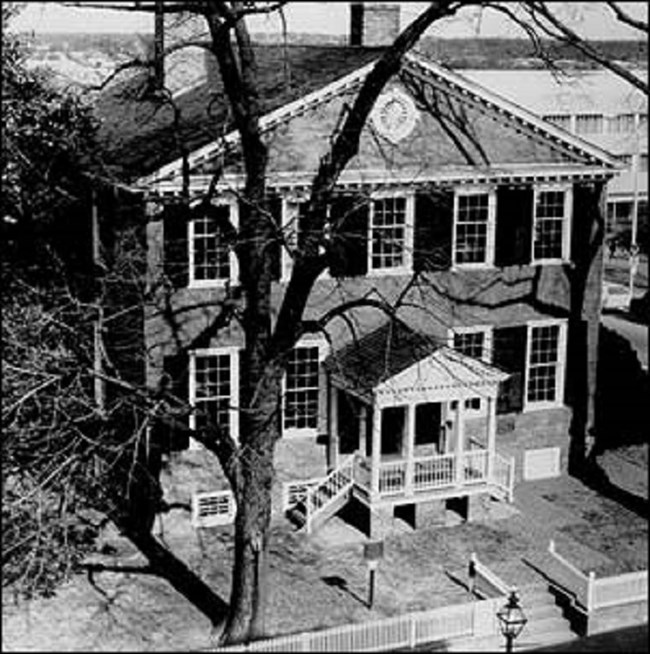

Photo 2: Exterior side view, John Marshall House.

This two-and-one-half-story brick house is an example of Federal architecture, a popular style of the 1790s in America. During Marshall's time the house was surrounded by five outbuildings: a kitchen, carriage house, laundry, law office, and smokehouse. The slaves lived on the second floors of the laundry and kitchen buildings.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. The Federal style architecture is known for its overall symmetry and balance. Examine Photos 1 & 2 and make note of the different architectural details on Marshall's house that demonstrate these attributes. Does this style seem fitting of a Supreme Court judge? Why?

2. Locate photographs or drawings of the homes of other great Virginians of the founding era, such as Jefferson’s Monticello, Madison’s Montpelier, and Washington’s Mount Vernon. How does Marshall’s house differ from the houses and surrounding properties of these other Virginians of his time?

Visual Evidence

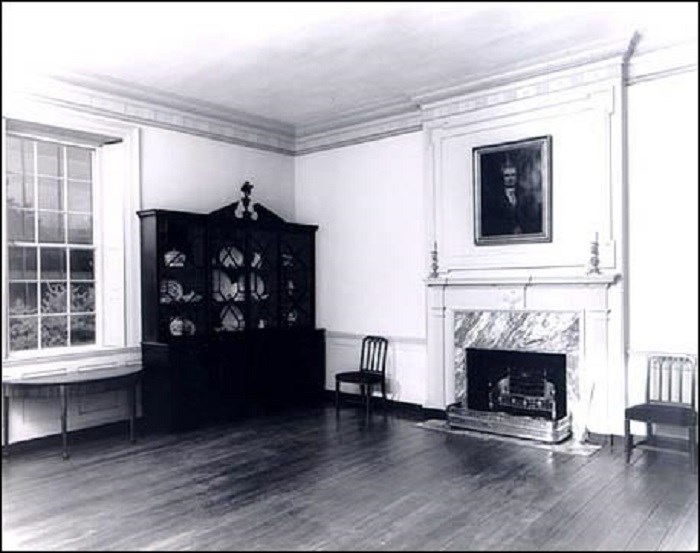

Photo 3: Withdrawing room, John Marshall House.

Courtesy of Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.

Photo 4: Dining room, John Marshall House.

Courtesy of Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.

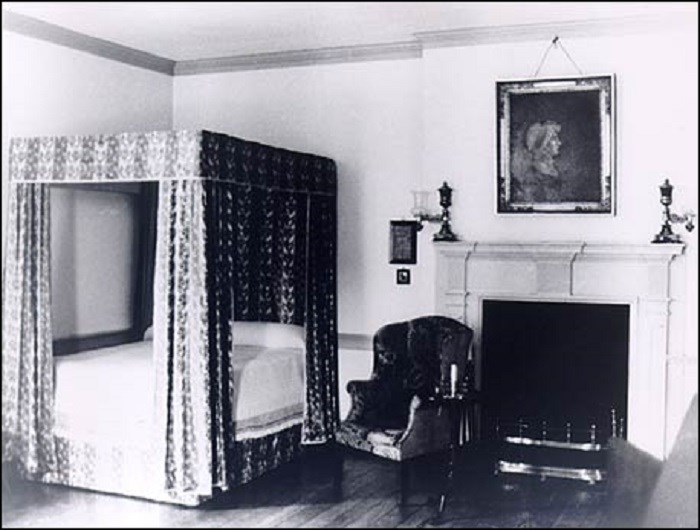

Photo 5: Master bedroom, John Marshall House.

Courtesy of Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.

The furnishings in each room are authentic pieces from the period when John and Polly Marshall occupied the house. The John Marshall House remained in the possession of his descendants until 1909, when it was acquired by the city of Richmond. In 1911 the care of the house was turned over to the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA). Today the APVA operates the house as a museum.

Questions for Photos 3-5

1. Write a paragraph on your impression of the rooms and the furnishings of the Marshall home. What is revealed or suggested about the lifestyle and standard of living of the Marshall family?

2. List similarities and differences between the rooms and furnishings of Marshall’s house and your own home.

3. Why might the APVA have been interested in preserving Marshall’s house?

4. Does the early date of their acquisition seem surprising? What does this reveal about the way Marshall’s house was viewed in the early 20th century?

Putting It All Together

The following activities allow students to further explore the people and the qualities that we associate with greatness.

Activity 1: Assessing Public and Private Qualities Associated with Greatness

Have students review the readings of this lesson and work in small groups to identify and discuss the qualities or characteristics of Marshall that constituted his greatness. Remind them to consider the relationship of his civic virtues and personal values--the public and private facets of his character--to his achievement of greatness. Finally, have each group identify two or three persons of the present whom they regard as great and compare their personal characteristics and values with those of Marshall. If students do not have information about the people they have selected, ask them to decide what they would need to know. Then ask them where they could find that information. Have each student pick one of their group’s candidates for greatness, research more about his or her life and accomplishments, and write an essay on the qualities that person possesses. Read some of the essays aloud in class.

Activity 2: Inquiry on the Landmark Supreme Court Opinions of John Marshall

Have students conduct inquiries on the greatest Supreme Court decisions and opinions of Chief Justice Marshall. A useful source for this project is The Constitution and Chief Justice Marshall by William F. Swindler (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1978). Landmark cases students might select include: Marbury v. Madison (1803), McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819), Cohens v. Virginia (1821), and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). In examining and reporting on each case, have students identify (a) the origin and constitutional issue of the case; (b) the Court’s opinion on the issue; (c) public reaction (such as Spencer Roane’s criticism of the decision in McCulloch v. Maryland); (d) the defense of the decision, whether by Marshall or someone else; and (e) the significance of the case for today’s operations of American government and constitutional law. Have students write a newspaper editorial supporting or opposing one of these decisions.

Activity 3: Historic Sites in the Local Community

Have students conduct research to find a historic site in their own community that is associated with an important figure. Ask students to investigate the following questions and prepare a written report: What did the individual do to achieve distinction? How are the site and the individual related? How and why was the site preserved? Was a local or state organization responsible for preserving the site, as was the case with Marshall’s house? How, why, and when did that organization get started? Have a few students read their reports aloud and then hold a classroom discussion on whether or not students feel it is important to preserve historic sites that are associated with important persons of the past.

"The Great Chief Justice" at Home--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at "The Great Chief Justice" at Home, students will meet John Marshall, who led the U.S. Supreme Court from obscurity and weakness to prominence and power in the early 19th century. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Library of Congress: American Memory Collection

Search the American Memory Collection Web page for a variety of historical resources on John Marshall. Included on the Web site are historic photographs of John Marshall and his homes, as well as correspondence regarding several of his cases. For more information, search on related terms such as U.S. Supreme Court, constitution, or the cases mentioned in the lesson such as Dartmouth College v. Virginia.

National Constitution Center:

Constitution Basics & The Constitution in our History

Visit the National Constitution Center Web page to better understand the U.S. Constitution and how it relates to our nation's history and understand the functions and duties of the U.S. Supreme Court and U.S. Supreme Court justices.

Federal Judicial Center

The History of the Federal Judiciary portion of the Federal Judicial Center’s Web Page presents basic reference information about the history of the federal courts and the judges who have served on the federal courts since 1789, including John Marshall.

U.S. Supreme Court

Visit the U.S. Supreme Court Web page for an overview of the Supreme Court and its constitutional interpretation, traditions, procedures, and members.

Tags

- supreme court of the united states

- constitution

- john marshall

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- virginia

- virginia history

- civics

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- shaping the political landscape

- federal

- north carolina

- north carolina history

- constitution history

- supreme court

- historic preservation

- historic preservation education

- twhplp