Last updated: April 1, 2020

Article

"My Dearest You Never Could Have Crossed"

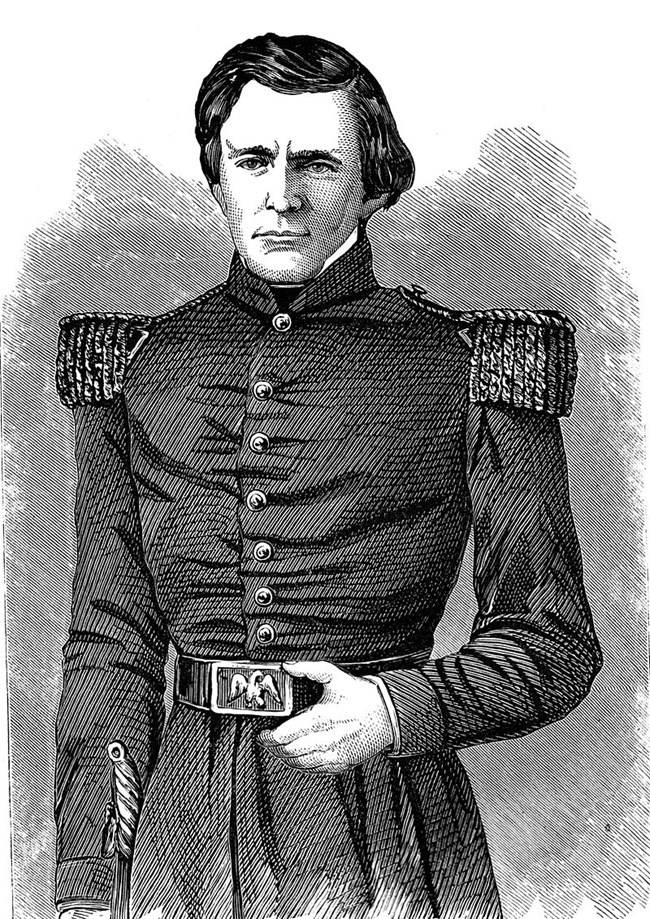

The Grant family’s life was once again disrupted when First Lieutenant Grant (who had been brevetted to the rank of Captain by this time) and the 4th U.S. Infantry were ordered to leave Madison Barracks in Sackett’s Harbor, New York, for Columbia Barracks, Washington Territory in July 1852. Lacking the infrastructure to make the trek over land, the 4th Infantry was required to sail aboard the steamboat Ohio south towards the Isthmus of Panama. After crossing Panama the ship would head northwest to San Francisco, upon which the regiment would make its way to Columbia Barracks (later renamed Fort Vancouver). Julia Grant, pregnant with their second child and caring for their two-year-old son Frederick, wanted to accompany her husband on the trip. “I began to think it would be most pleasant,” she later recalled, “seeing the bright and beautiful tropical foliage” in Panama and remaining close to Ulysses. Lieutenant Grant, however, worried about his wife’s health. She remembered that “I shed tears . . . [he] begged me not to grieve about it, as the doctor and all advised that I should not go now.” As the steamer set sail for California on July 5, Julia had already made her way to Bethel, Ohio, to be with Ulysses’ parents.

Lieutenant Grant’s intuition proved not only right, but life-saving. As the ship arrived at the Isthmus of Panama, a deadly cholera epidemic ravaged the 4th Infantry soldiers and their families. Little was known about the origins of cholera at this time. In fact, a similar outbreak that occurred three years earlier in St. Louis was prolonged by the faulty belief that the sickness was caused by unhealthy air. In reality, cholera is caused by the consumption of unsafe water and food that often contains human waste. Symptoms include muscle cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea, all of which can lead to death.

As the regiment’s quartermaster, it was Grant’s job to procure enough food, clothing, transportation (such as mules) and other supplies for the troops and their families. But the cholera outbreak made him a nurse and caretaker for all aboard. One passenger later praised Grant’s work as caretaker, saying that “his work was always done, and his supplies always ample and at hand . . . He was like a ministering angel to us all.” Nearly one third of all passengers—more than 100 total—died of cholera by the time the regiment arrived in San Francisco. Among the dead included some of Grant’s fellow soldiers, their wives, and twenty children under the age of two. Major John Gore, a good friend of the Grants, was among those who perished. Nevertheless, Grant’s actions almost certainly kept that number from rising any higher. Meanwhile, Julia gave birth to the couple’s second child, Ulysses S. Grant, Jr., on July 22. “My dearest you never could have crossed the Isthmus at this season,” a relieved Ulysses wrote to Julia as the Golden Gate, another steamer the 4th Infantry traveled on, temporarily stopped in Acapulco, Mexico. “The horrors of the road, in the rainy season, are beyond description.”

The tragedy at Panama stayed in Grant’s mind for the rest of his life. In his first address to Congress as President in 1869, Grant expressed his support for a survey of the Isthmus of Panama by the U.S. Navy and eventual construction of a canal. Several surveys were undertaken between 1870 and 1875, but Grant came to believe that such an undertaking was not feasible. When an American agent for a French surveying business in the region contacted Grant offering the company’s directorship in 1881, he politely declined. “I do not believe the project feasible in the first place, and I should oppose it at any rate under any European management," Grant responded. "My judgement is that every dollar invested in the Panama Canal, under the present scheme of a thorough cut, or sea level, will be sunk without any return to the investors.”

Nearly twenty years after Ulysses S. Grant died, the U.S. government acquired land in what would become the Panama Canal Zone. It took ten years to build the present-day Panama Canal, which was completed in 1914.