E.F Leffingwell

Introduction

A tent ring is generally described by archaeologists as a circular pattern of stones marking the spot where a tent or tipi once stood (Figure 4). These stones were placed on the edges of the tent wall flaps to keep the structure in place, much the same way tent stakes are used with modern tents. At first glance tent rings appear much the same across the landscape. Indeed, I’ve heard comments such as “if you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all”, and “tent rings are boring”. Why then should we study such an apparently simple construction? What can tent rings tell us about the people who left them behind? This project reveals the answer is quite a lot.

Ethnographic Analogy Archaeologists cannot travel through time. A great deal of what we understand about the past comes from reasonable com-parisons made with historical records and ethnographic accounts. Written records of cultural practices, food gathering strategies, clothing production, shelter construction and settlement patterns of the Nunamiut Eskimos, known as the “Inland Eskimo”, give us most of our sources for comparative purposes in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve. Ethnographers and historians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century recorded Eskimo methods for constructing a domed tent, known as an itchalik. These tents were made by draping caribou skins over a frame of lashed willow poles (Figure 1-2) (Campbell 1998, Lee and Reinhardt 2003). Researchers recorded the locations of the camps, and the time of year for tent use. Although Nunamiut people built sod-walled houses, known as ivrulits for more permanent winter dwellings, they still used the caribou skin tents in winter when camp relocation became necessary (Figure 1) (Ingstad 1954).

E.F Leffingwell

Knowing how and why tent rings were formed led us to pose this most basic question: are all the tent rings in Gates of the Arctic attributed to Nunamiut occupations? We know that people have occupied the Brooks Range for over 12,000 years. Archaeologists have outlined a broad culture history that includes prehistoric groups known as Paleoindians, Northern Archaic, Arctic Small Tool tradition, and historic Gwich’in and Nunamiut peoples (Campbell 1962). A critical need for surviving in the arctic is adequate shelter. Did the previous groups who inhabited Gates of the Arctic leave tent rings behind and if so, what characteristics do they have that would distinguish them from those of the most recent group?

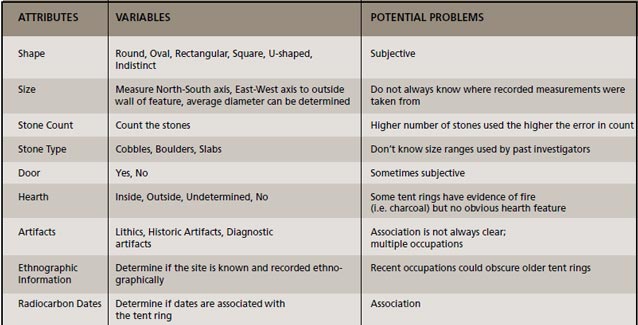

Research Methods and Goals To attack this problem I created a database to systematically record defined attributes of every tent ring referenced in and around Gates of the Arctic. I used the National Park Service ASMIS archaeological database to locate all the known archaeological sites that reported the presence of a tent ring. I then searched out the original references, field notes, site reports, published and unpublished articles, master’s theses, and dissertations to fill in this tent ring database. From these records I found 284 known tent rings referenced, with varying levels of description. Some reports simply stated there was a tent ring present, while others were more detailed, documenting size, shape, and the number of stones used. Often cultural affiliation was assigned, and not surprisingly, most were attributed to Nunamiut Eskimos. I compiled a list of attributes which could be used for comparison. Though not comprehensive, the table in Figure 3 offers a list of the most useful attributes for systematically quantifying differences and similarities between tent rings.

Andrew Tremayn

A perusal of the attributes assembled showed that many of the tent rings varied widely in size, shape, and number of stones used, and even with artifacts they were found associated. One tent ring reported from Anuktuvuk Pass was associated with charcoal dating to nearly 7,000 years old (Campbell 1962). Archaeologists, however, have learned that it can be misleading to take evidence at face value. For example, a recent tent ring could have been constructed on top of a more ancient occupation that left the tools and charcoal behind. The predominant interpretations in the literature suggested uncertainty about artifact associations with most of the tent rings.

With these questions in mind, the Gates of the Arctic archaeology crew set out for two months of field work in the park. We surveyed hundreds of miles by hiking to places that looked good to camp or spot for game. We surveyed along the Nigu River, Killik River and Easter Creek, and all around Agiak Lake. This work allowed me to revisit 51 of the known tent rings to re-record them for this study. In the process, our team discovered and systematically recorded another 50 previously undocumented tent rings. The main goal of our field work was to accurately record tent ring dimensions, to determine if artifact associations were valid, and to collect bone or associated organic material, such as charcoal, from which we could obtain a radiocarbon date.

Results

Of the 334 tent rings in my database, I personally recorded 101 of them. I found a great many differences evident in the record. I first used ARCMap Geographical Information System to plot the locations and attributes of the sites with tent rings. From this I was able to note that tent rings are much easier to find above tree line, and that some sites have many more tent rings than other sites. While most sites only have one tent ring, indicating a small hunting party, some areas such as Agiak Lake have over 80 tent rings represented (Wilson and Slobodina 2007).

Andrew Tremayn

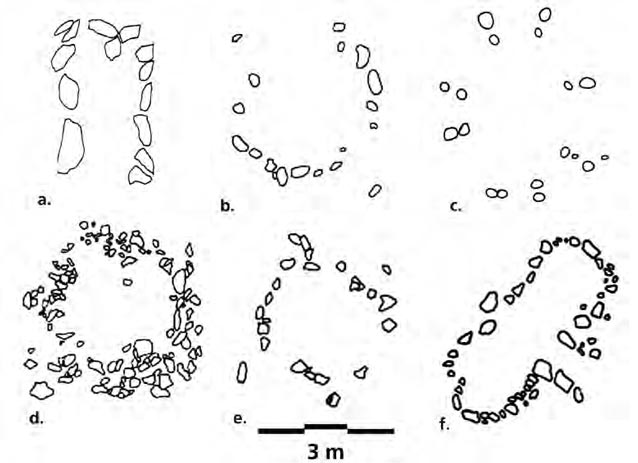

I used the database to systematically compare each tent ring. After a series of comparative attempts I finally stumbled upon the most useful measure of difference. A quick glance at the different shapes, sizes and stone counts clued me into the wide variety of styles that exist here (Figure 5). I compared the basic measurements of the structures with the artifacts and radiocarbon dates. Some immediate patterns emerged. If associated with artifacts, tent rings were either associated with stone tools or debris from producing stone tools, or were found with historic artifacts. By comparing stone count, a significant correlation between increased stone count and the presence of stone tools, and between fewer stones and historic artifacts could be seen.

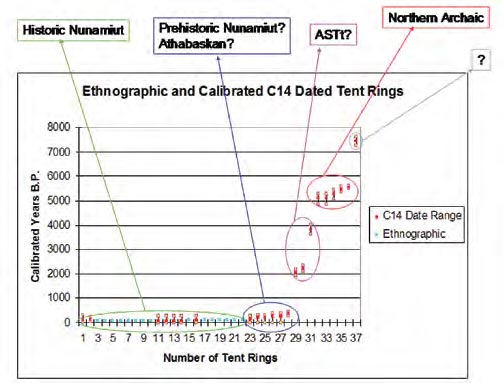

Although this classified historic tent rings and pre-historic tent rings, I wanted to take the analysis further. To accomplish this I needed better chronological control over my data; I needed to know the age of the tent rings. From our charcoal and bone samples, and from samples previously collected, I was able to acquire 22 absolute dates associated with tent rings (Figure 8). Along with this information, I used known ethnographic accounts of sites occupied by Nunamiut Eskimos, and diagnostic artifacts attributed to other well-defined pre-historic groups. A diagnostic artifact is a type of artifact that exhibits characteristics only associated with a specific group. With better time markers now at my disposal, I divided the tent rings into groups based on age and cultural identification. Obviously, not all tent rings have diagnostic artifacts or associated remains that can be dated, but of the ones that did, some clear patterns emerged.

A. Wilson

Tent Ring Types Found in Gates of the Arctic

The youngest tent rings found in Gates of the Arctic can be attributed to historic canvas wall tent use (Figure 5a). Gubser (1965) reports that canvas replaced caribou skins for Nunamiut tents in the early 1900s, and by the 1950s commercial tents stretched over spruce log frames were in common use. These stone features often have dimensions similar in size to wall tents, 3 x 4 meters. At least 34 tent rings in the dataset can be assigned to this type.

The Nunamiut itchalik left behind rather different rings, such as the one presented in Figure 4. They tend on average to be round or oval in shape, about 3.3 meters in diameter, and constructed of 20 stones or less, on average. The Nunamiut itchalik is the most common tent ring found in Gates of the Arctic; at least 99 have been positively identified.

A third type of tent ring can be attributed to Gwich’in Athabascan construction. According to ethnographic accounts, the Gwich’in moved into parts of Gates of the Arctic in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries before being displaced by rival Nunamiut people (Hall 1969). Although historically Athabascan territory is east of Gates of the Arctic and south of the Brooks Range, 16 tent rings are attributed to Athabascans. These tent rings tend to be larger in size than Nunamiut tent rings and made of more stones. They also tend to have a formal lined hearth present in the interior (Figure 7).

According to Eskimo informants, “the Kutchin were called uyagamiut (inhabit-ants of rocks) by the Eskimos because they built stone houses” (Hall 1969). Nothing resembling this comment has been found and certainly attributed to Athabascans, but within the park at least one site has the most unusual tent ring of all (Figure 9). This tent ring is likely not of Gwich’in construction but rather is thought to be an example of a Nunamiut karigi. A karigi is a traditional Eskimo men’s house.

A fifth type of tent ring was that of the Arctic Small Tool tradition, dating between 2,000-4,000 years ago. At this time only 8 tent rings of this type have been located. They appear quite similar to the Nunamiut itchalik in size, shape and stone count (in Figure 5 compare b and e), but associated diagnostic tools and radiocarbon dates attest to their greater antiquity (Figure 6).

Another even more ancient type can be attributed to people of the Northern Archaic tradition (Figure 5d). These tent rings, 61 of which are thought to be present in the Brooks Range, tend to be round or oval, very large and comprised of on average 50 or more stones.

Pete Christian

Conclusion

This study illustrates an important point about archaeology in Gates of the Arctic; mainly that there is much we still do not know about the cultures who occupied this region over the past 12,000 years. By looking at this seemingly unimportant feature in closer detail I have learned that tent rings hold a great deal of information about the people who constructed them. We can address issues of group size, sedentism, and also work to understand differences and changes that occurred with the various groups who lived here in the past.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the National Park Service, The Geist Fund and the University of Alaska for funding this project. Thanks to Jeff Rasic, Dan Odess and the field crew, Aaron Wilson, Natalia Slobodina, Jay Flaming and Cassie Flynn.

REFERENCES

Campbell, John. M. 1962.

Cultural succession at Anaktuvuk Pass, arctic Alaska. In Prehistoric Cultural Relations Between The Arctic And Temperate Zones Of North America, edited by J.M. Campbell, pp. 39-44, vol. 11. Arctic Institute of North America. Montreal.

Campbell, John M. 1998.

North Alaska Chronicle: Notes from the End of Time. Museum of New Mexico Press. Santa Fe.

Gubser, Nicholas J. 1965.

The Nunamiut Eskimos: Hunters of Caribou. Yale University Press. New Haven and London.

Hall, Edward S. 1969.

Speculations on the Late Prehistory of the Kutchin Athabaskans. Ethnohistory 16:317-333.

Ingstad, Helga. 2006 [1954].

Nunamiut: Among Alaska’s Inland Eskimos. Commemorative edition. The Countryman Press. Woodstock, Vermont.

lee, Molly, and Gregory A. Reinhardt. 2003.

Eskimo Architecture. University of Alaska Press. Fairbanks, Alaska.

Wilson, Aaron, and Natalia Slobodina. 2007.

Two Northern Archaic Tent Ring Settlements at Agiak Lake, Central Brooks Range, Alaska. Alaska Journal of Anthropology 5(1): 43-60

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science- Volume 8 Issue 1: Connections to Natural and Cultural Resource Studies in Alaska's National Parks.

Last updated: July 26, 2021