Last updated: September 15, 2023

Article

Women at Antietam

Library of Congress.

The Battle of Antietam and its aftermath were like nothing Americans had experienced before. On one single day, September 17, 1862, over 23,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing. Afterwards, the battlefield became a huge hospital and burial ground. Local farmers and townsfolk had their houses, barns, and churches turned into field hospitals. In addition to soldiers with wounds of all types, there were soldiers sick with typhoid fever, dysentery, and other diseases often brought on by contaminated drinking water, filth, and the sheer number of sick and wounded people living in close quarters.

One topic often overlooked by historians is the contributions of women both during and after the battle. Women served disguised as male soldiers, they served as nurses, cooks, and laundresses. Women served in Ladies’ Relief Societies, in the U.S. Sanitary Commission, and in the U.S. Christian Commission. The Daughters of Charity, a Catholic religious order from Emmittsburg, Maryland, also responded in the aftermath of the battle. Many unnamed women from the Sharpsburg community helped care for the sick and wounded as well. The Herald of Freedom and Torch Light, a newspaper printed in Hagerstown, MD wrote:

“A Vast Hospital-From Hagerstown to the Southern limits of the county wounded and dying soldiers are to be found in every neighborhood and in nearly every house. The whole region of country between Boonsboro' and Sharpsburg is one vast hospital. Houses and Barns are filled with them, and nearly the whole population is engaged in waiting on and ministering to their wants. In this town the Washington House, County Hall, and Lyceum Hall have been appropriated to the use of the wounded, and our citizens, especially the ladies, are untiring in their efforts to relieve them.”

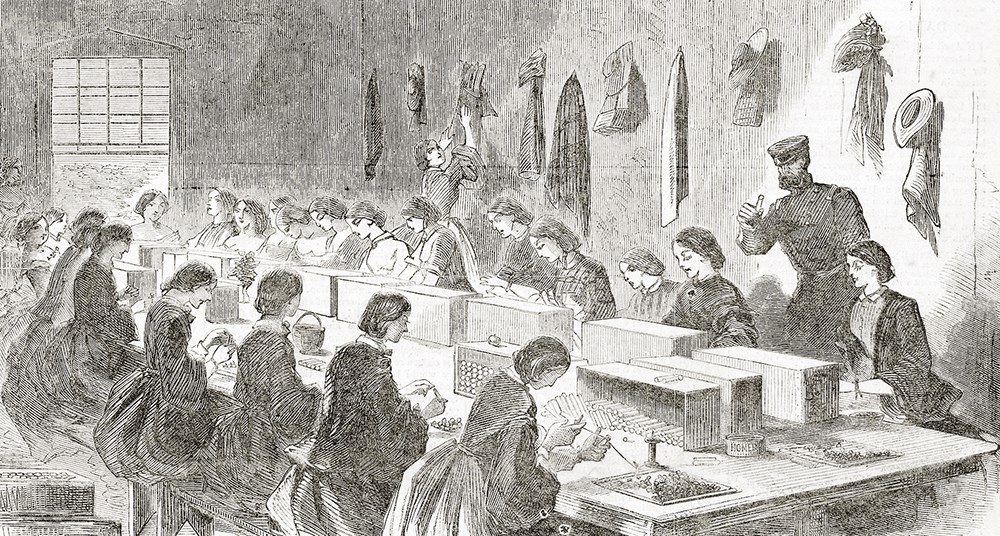

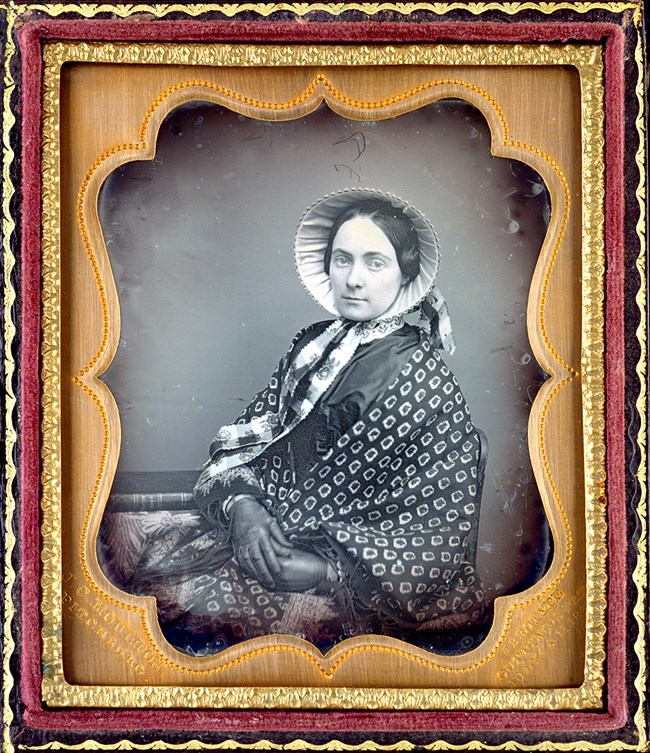

Historian Susan-Mary Grant wrote, “Nineteenth-century warfare was a man’s game, no doubt, but it was also a woman’s business. War work — at home or on the battlefield — presented women with new social and political opportunities, even as traditional social structures altered in men’s absence.” In the 19th century, society’s idealized version of a women was someone who was adept at domestic skills, quiet and demure, would marry or was married, supported her husband and was protected by him, and had children (in wedlock). Upper- and middle-class women were to be mothers and wives charged with maintaining or directing the maintenance of a household. As historian Susan M. Cruea wrote their “choices were limited to marriage and motherhood, or spinsterhood.” Additionally, they were responsible for the moral and religious upbringing of their children. The idealized Victorian woman was very different from many real women, especially those who were lower- or working- class. Lower-class women’s roles varied, they took care of their homes and children, and some were forced to work out of necessity. They served as domestic servants, laundresses, cooks, farm laborers, piecework seamstresses, and factory workers. They sometimes took in boarders to make ends meet. Some were enslaved; forced to work for free and subjected to violence and sexual assault.

Library of Congress

Angel of the Battlefield

One of the more famous women associated with the Battle of Antietam was Clara Barton. She, along with a few male assistants, travelled from Washington, D.C. with several wagonloads of medical supplies for the Union Army. She arrived at the battlefield at about noon on the day of the battle somewhere near the northern end of the battlefield. Many years after the Civil War, Clara Barton wrote an essay that detailed in part her experience at Antietam:

There was a big cornfield, and we drove in, and up towards an old barn which was standing in the midst. My men unharnessed the mules and tied them to the wheels and we were ready for work. They were always my helpers…I followed them through the corn and came upon the house. It had a high, broad verandah, and on this every kind of thing that pretended to be a table was standing, and on the tables were the poor men, and beside them the surgeons. They were the same with whom I had just been at the second Bull Run.

"The Lord has remembered us!" "You are here again"

"And did you want me?" I asked.

"Want you! Why, we want you above all things, and we want everything."

"I have everything," I replied

"Look here," he said, "see what we need, and how much we need it, we have no more chloroform, no more bandages nor lint, no more liquor, nothing. See here" and he showed me some poor fellows whose raw new wounds were actually dressed with those rough corn leaves.

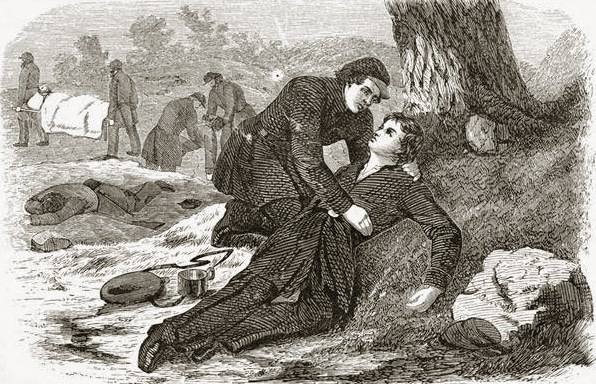

… That was the point I always tried to make, to bridge that chasm, and succor the wounded until the medical aid and supplies should come up. I could run the risk; it made no difference to anyone if I were shot or taken prisoner and I tried to fill that gap. My men unloaded the wagons, and brought up everything the good women of the country had provided; the wounded kept pouring in, and we kept working over them.

Clara Barton continued caring for the wounded during the battle, unconcerned for her own safety. She later wrote that while helping give a wounded soldier a drink of water, "A ball has passed between my body and the right arm which supported him, cutting through his chest from shoulder to shoulder. There was no more to be done for him and I left him to his rest. I have never mended that hole in my sleeve. I wonder if a soldier ever does mend a bullet hole in his coat?" After the battle she stayed or a few days helping wherever she could, eventually due to exhaustion and typhoid fever, she returned to Washington, D.C. Almost twenty years later, she founded the American Red Cross.

Because of her extensive correspondence, writings, and association with the Red Cross, Clara Barton is the most famous women associated with the Battle of Antietam. But many other women were present both before and after the battle. In fact, Clara Barton encountered sixteen- year-old Mary Galloway, who had disguised herself as a male solider. After being shot in the neck and laying in a ditch for over a day, Mary was finally brought to a field hospital and refused to let the surgeon examine her, fearful her secret would be found out. Clara Barton talked to the young soldier. “Still another face that peered anxiously through that sooty haze looked to Clara too soft to be a soldier; the boy was suspiciously hesitant to have his wounded breast dressed. After gentle probing, Barton ascertained that the soldier's name was Mary Galloway. Barton could sympathize with this girl's spirited defiance of custom and her determination to join her menfolk at the front. She shepherded and shielded the girl, and subsequently located her lover in a Washington hospital. In later years Barton liked to recall that the two had named their eldest daughter for her."1

Edmonds, Sarah Emma Evelyn. "The Female Spy of the Union Army." United States: De Wolfe, Fiske, 1864. 271.

Women Soldiers in Disguise

Women and girls had many reasons for disguising their gender and joining the army. Some, like Mary Galloway, were following loved ones, others wanted to experience adventure and leave behind Victorian gender constraints, others joined out of patriotism, and one woman, Sarah Emma Edmonds, left her home in Canada to escape an abusive father and an arranged marriage to an older widower. Edmonds adopted the name Franklin Thompson. Just before the Battle of Antietam she was serving as a mail carrier in the Army of the Potomac and during the battle, she helped the wounded. Edmunds definitely served in the military disguised as a man and did receive a soldier’s pension after the war, but some historians say her memoir is embellished.

In her 1865 memoir, Edmunds writes that she found a mortally wounded soldier who turned out to be a female soldier in disguise:

In passing among the wounded after they had been carried from the field, my attention was attracted by the pale, sweet face of a youthful soldier who was severely wounded in the neck....The soldier turned a pair of beautiful, clear, intelligent eyes upon me for a moment in an earnest gaze, and then, as if satisfied with the scrutiny, said faintly: “Yes, yes; there is something to be done, and that quickly, for I am dying.

I can trust you, and will tell you a secret. I am not what I seem, but am a female. I enlisted from the purest motives, and have remained undiscovered and unsuspected. I have neither father, mother nor sister. My only brother was killed to-day…I have performed the duties of a soldier faithfully, and am willing to die for the cause of truth and freedom…I wish you to bury me with your own hands, that none may know after my death that I am other than my appearance indicates.

I remained with her until she died, which was about an hour. Then making a grave for her under the shadow of a mulberry tree near the battle-field, apart from all others, with the assistance of two of the boys who were detailed to bury the dead, I carried her remains to that lonely spot and gave her a soldier’s burial...

In 1865 the Hagerstown Herald and Torchlight published a small article about the remains of a female Union soldier being discovered. There is no way to know if this was the same woman Edmunds supposedly encountered or another anonymous female soldier. The article said, “Mr. Good who is actively engaged collecting a list of the names of the dead on Antietam battle field, and other information for the use of the trustees, has discovered that a woman acting as a Union soldier in uniform was killed in that great battle. We have not learned her name or residence, but presume Mr. Good has all the information by which her friends will be able to identify her remains.”

An unidentified female Confederate soldier was found by a Union burial party after the battle.

In his memoir, Private Mark Nickerson of the 10th Massachusetts Infantry wrote:

A Sergeant in charge of a burying party from our regiment reported to his Captain that there was a dead Confederate up in the cornfield whom he had reason to believe was a woman. He wanted to know if she should be kept separate, or brought along with the others. The Captain after satisfying himself that this Confederate was a woman ordered that she be buried by herself. The news soon spread among the soldiers that there was a woman among the Confederate dead, and many of them went and gazed upon the upturned face, and tears glistened in many eyes as they turned away. She was wrapped in a soldier's blanket and buried by herself and a head board made from a cracker box was set up at her grave marked "unknown Woman CSA."

Nothing in my experience up to that time affected me as did that incident. I wanted to know her history and why she was there. She must have been killed just as the Southerners were being driven back from the cornfield.

In addition to Galloway, Edmunds, and the unknown female soldier, there is some evidence that five other women served at Antietam disguised as male soldiers. Catharine Davidson of the 28th Ohio lost her arm but survived the battle. Other female soldiers include a pregnant woman from New Jersey, an anonymous Confederate soldier, Rebecca Peterman of the 7th Wisconsin Infantry, and (possibly) Ida Remington. Ida Remington claimed she had been at the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam. Sources indicate that she did serve in the war but are conflicting as to whether or not she was in the area at the time of the battle. Incidentally, she was discovered to be a woman when she was arrested for “public drunkenness” in 1863.

Nurses, Cooks, and Laundresses

Women soldiers were a rarity. However, as historian Claire Prechtel-Kluskens wrote, “More than 21,000 Northern women were employed as nurses, cooks, matrons, laundresses, seamstresses, waitresses, and chambermaids.” Women also participated through Ladies’ Aid Societies, the United States Sanitary Commission, and religious organizations. Typically, working- or lower- class women were laundresses or employed in menial jobs and middle- and upper-class women served as nurses. It was common to have women attached to regiments who were laundresses.

U.S. Army regulations allowed four laundresses per company (typically 100 soldiers). These women were sometimes the wives of enlisted men or non-commissioned officers, widows, enslaved women, or contraband [newly freed and escaped slaves who made it to the Union army]. While usually behind the lines, at least one laundress was right in the thick of the fight at Antietam. Charles C. Hale of the 5th NH Infantry wrote:

As our first brigade was forming to relieve them, (Meagher’s Irish Brigade attacking the Sunken Road) we saw “Irish Molly,” of the 88th New York, a big, muscular woman who had followed her husband in all the campaigns, and he a private soldier in the ranks. She was a little to the left of their line, apparently indifferent to the flying bullets, and was jumping up and down, swinging her sunbonnet around her head, as she cheered the Paddys on. Our regiment was maneuvering for position at the time, and the bullets that passed the Irishmen were pretty thick, so there was no time for anything else, as we were moving lively, but the glimpse that I got of that heroic woman in the drifting powder smoke, stiffened my back-bone immensely.

A more typical and well-known role for women was nursing. However, class extended to hospitals and nursing duties as well. Usually working-class women, especially Irish and African-American women would take over the hard labor and dirty work in hospitals such as cleaning, cooking, and laundry. Upper-class women sometimes oversaw hospitals and performed nursing duties. These duties included administering medicines, feeding soldiers, reading to the men, helping them write letters, and sometimes changing dressings. Occasionally these nurses would assist during operations, but this was not common practice. Women would have to be unencumbered by children and a husband in order to have the time to take on these duties. They would also have to have the financial means to travel, unless they were receiving a wage. Therefore, it was often widows and unmarried women who helped in the field and military hospitals.

Library of Congress

Class distinctions also dictated whether a woman could visit her husband in camp or in a hospital. Officers’ wives were generally allowed to visit their husbands in camp and if they were

wounded in hospitals. These women also had the means to leave home for short periods of time. Even if an upper-class woman had children, she likely had a paid domestic staff or enslaved African-Americans working for her who could run the household temporarily. Two examples of women, both upper class, who were able to visit their wounded husbands at Antietam were Arabella Barlow and Frances Richardson. Arabella Barlow joined the United States Sanitary Commission as a nurse. She joined as a volunteer, in part, hoping to stay close to her husband, Colonel Francis Barlow, who was at the front lines. Just before the Battle of Antietam, Arabella was in Baltimore. She arrived at the battlefield the day of the battle just as her husband was taken off the field wounded. George Templeton Strong, founder of the United States Sanitary Commission, saw her that day. He wrote, "In the crowd of ambulances, army wagons, beef- cattle, staff officers, recruits, kicking mules, and so on, who should suddenly turn up but Mrs. Arabella Barlow, ne'e Griffith, unattended, but serene and self-possessed as if walking down Broadway. She is nursing the Colonel, her husband (badly wounded), and never appeared so well. Talked like a sensible, practical, earnest, warm-hearted woman, without a phrase of hyperflutination (sic).” Francis Barlow survived his injuries, but Arabella died in in 1864 from typhus.

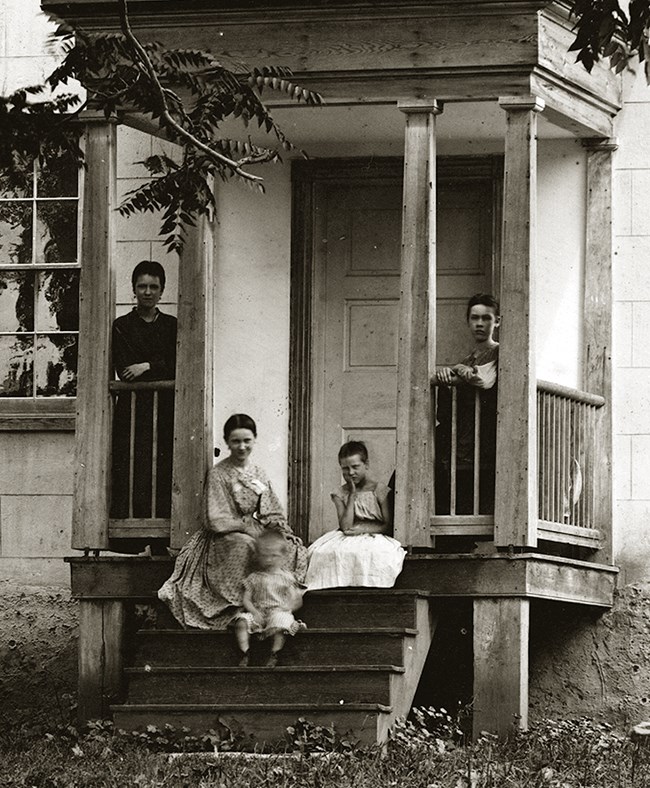

Another wife who was able to nurse her husband after the battle was Frances Richardson. Her husband, Major General Israel Richardson, was wounded at Bloody Lane during the battle when a shell fragment stuck him. Eventually moved to the Pry House, General McClellan’s headquarters, Richardson was treated for his injury and for pneumonia. When she heard about her husband’s injury, Frances, along with her sister-in-law travelled to Sharpsburg to care for him. Frances wrote, “Israel is slowly but steadily improving [but he] has grown very thin and very weak. He is very much depressed, not at all like himself, and inclined to look on the dark side, more than is good for him.” While he was recovering from his wound, Israel Richardson was visited by President Lincoln at the Pry House. Richardson’s wound became infected and he died on November 3, 1862. Frances and his sister-in-law had his body embalmed and accompanied his remains back to his home state of Michigan.

Some women had no loved ones in the army but felt called to help. Upon learning about the massive casualties at the Battle of Antietam, 39-year-old, Elizabeth Tuttle, left home in New Jersey without telling anyone. In a March 3, 1863 letter to her niece Hattie, she wrote about what she experienced in the field hospitals:

I presume you have heard before this about my being at this place. I have not written any letters to anybody but Mary since I left there last Sept. and went to the battlefield after the battle of Antietam on the 17th of Sept. I staid [sic] in a field hospital thirteen weeks and then came to Harpers Ferry where I have been ever since. I don’t think I ever enjoyed myself as well in my life as since I joined the army. I was fortunate enough to fall in company with some very nice ladies at first and we have been together ever since- I have thought a great many times about writing to you but have never seemed to find time to write as many particulars as I wished to when I should write at all. I believe Mary has pretty full notes of my adventures out here and I should be glad to tell you them some time…

Elizabeth Tuttle never married and became a school teacher after the war. Teaching was one route middle-class women could take to remain independent without relying on a husband or relatives. Judging from her letter, in addition to helping wounded soldiers, it seems that she was also looking for excitement and adventure.

Library of Congress

Another nurse at Antietam was Helen L. Gilson. Of her time caring for wounded soldiers at various battlefields she said, “I have tested myself sufficiently under shot and shell to know that in danger I can be calm. And that is needed on the field.” Later in the war, while nursing at the hospital camp at City Point, Gilson realized that standards at hospitals for African American soldiers were much lower than those for hospitals for their white counterparts. She made it her mission to bring down mortality rates and improve conditions in these hospitals.

Other avenues for women to help with the war effort were Sanitary Fairs and the various Ladies’ Aid Societies. Sanitary Fairs were events that raised money for sick and wounded soldiers. These fairs were extremely successful, raising over fifty million dollars during the war. The money raised was given to various relief organizations. The two most famous relief organizations were the United States Sanitary Commission and the United States Christian Commission. The Sanitary Commission focused on the physical needs and comfort of the soldiers; while the Christian Commission focused more on their spiritual needs. Both organizations were founded by men. Women faced discrimination and exclusion in these groups, but they were eventually allowed to join and assist in hospitals and other areas. A ladies’ auxiliary to the Christian Commission, was founded in 1864. Christian Commission delegates, including at least one unnamed woman were present in the field hospitals after the Battle of Antietam. The United States Sanitary Commission’s main purpose was to raise money for and distribute supplies to wounded and sick soldiers. There was also an African-American branch of the Sanitary Commission founded in 1863 called The Ladies’ Sanitary Association.

Anna Morris Holstein, a wealthy woman from Pennsylvania, wrote about her experience serving in the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She published her memoirs in 1867. Before Antietam she had participated in the war effort by volunteering with various ladies’ aid societies. After the Battle of Antietam, she initially hesitated to go with other women in her ladies aid group to nurse the wounded. Eventually she relented and she and her husband joined the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She wrote,

But when my husband returned, soon after, with the sad story that men were actually dying for food, home comforts and home care; lying by the roadside, in barns, sheds, and out-houses; needing everything that we could do for them, I hesitated no longer, but with him went earnestly to work in procuring supplies of food, medicine, and clothing. Through the kindness of friends and neighbors, we were enabled to take with us a valuable supply of articles that were most urgently required…

As I passed through the first hospitals of wounded men I ever saw, there flashed the thought-this is the work God has given me to do in this war. To care for the wounded and sick, as sorrowing wives and mothers at home would so gladly do, were it in their power. From the purest motives of patriotism and benevolence was the vow to do so, faithfully, made. It seemed a long time before I felt that I could be of any use-until the choking sobs and blinding tears were stayed; then gradually the stern lesson of calmness, under all circumstances, was learned.

We found the men, who had so bravely fought, still scattered over the hardly-contested field.

Of her experience, she said, “The name of Antietam is ever associated in my mind with scenes of horror."

Antietam National Battlefield, National Park Service

Local women also helped after the battle. The Baltimore American mentioned the Hagerstown Ladies’ Relief Society and a Mrs. Susan Harry who “assembled at different houses, sewed bandages, scraped lint and made up such things as would relieve the sufferers, and from sun-up to sun-down. You could find them in every nook of the town, and through the country, searching for, begging and buying such articles as the sufferers might ask for or want. At morning, noon, and evening, you would see these ladies, accompanied by their husbands, children and servants, with baskets, buckets, pitchers and plates in their hands winding their way to the hospitals.” This article mentions servants, which indicates once again that it was middle or upper-class women who had the means and time to volunteer their time.

Women who lived on the farms located directly on the battlefield would have also helped as well. Many of their houses and barns had been turned into field hospitals. Mr. and Mrs. Roulette, who lived next to the famous “Bloody Lane,” had their barn converted into a Union hospital. Henry S. Stevens, a chaplain with the Fourteenth Connecticut Infantry wrote:

Bullets pierced it [the Roulette House] on the day of battle, and one huge shell tore through the west side, a little above the floor, and going through the parlor in an upward course passed through the ceiling and a wall beyond and fell harmless amid a heap of rubbish it had created, where we saw it many times that day. During the battle the rooms were stripped of their furnishings and the floors were covered with the blood and dirt and litter of a field hospital; yet when the writer was there two weeks later, on a trip to see our wounded in the hospital…, he found it cleansed, repainted and refurnished, and Mrs.

Roulette, a charming woman, presiding at a beautifully and bountifully spread table, with her husband and all her bright little ones safely and cozily about her.

In loss claims filed with the federal government after the battle, Mr. Roulette requested compensation for “for occupation and use of his house, barn and outbuildings for hospital purposes by Medical officers of General. McClelland's army, from Sept. 17 to 24, 1862, …that the property was taken in said county and state, for the use of, and used by the U.S. Army; that the buildings described were used as a hospital for several days after the Battle of Antietam." Sadly, the Roulette’s twenty month old daughter, Carrie May, died on October 26, 1862 from typhoid fever. Most likely she contracted this as a result of living next to the field hospital. The conditions in the hospitals were horrible and waste from humans and animals contaminated water supplies for the local families.

Library of Congress

Many women could not afford to visit their husbands in hospitals, or they were not able to leave home due to children or having to run a farm or business while their husband was in the military. However, some women did work as nurses and in other support positions to make a living. Historian Jane E. Shultz wrote, “Union nurses earned forty cents a day plus one ration. Women hired by hospitals as cooks and launderess-frequently black women hired on civilian contracts-made between six and ten dollars a month.” In comparison, Union privates made $13.00 per month and Confederate privates made $11.00 per month. In terms of Confederate nurses, they were paid in Confederate money which would be affected by both inflation and depreciation. Towards the end of the war, Confederate money was almost useless. Some examples compiled by National Archives archivist DeAnne Blanton show “Elizabeth Tatum was employed as a nurse at $10.00 Confederate a month; George W. Buckles was also a nurse, at $7.50 a month; William ("colored") was employed as a cook, with his $20.00 a month paid to R. Rogers; Teeny ("colored") was a laundress, with her $8.00 wages paid to L. B. Davis; S.A.R. Summerlin worked as a matron earning $18.50 a month.

These are some examples, but wages would have varied and in some cases these women would not get paid at all or chose to volunteer. "Working-class women also served as nurses, however, “’Cook’ and ‘laundress’ were reserved primarily for black women (free or slave) and white working-class women, even though pension records make clear that many cooks and laundresses did the serving work of nurses. Maria Bear Toliver, an enslaved woman from King William County, Virginia, fled to Washington in 1862, where she found work first at a contraband camp…and later as a ward nurse in a smallpox hospital for black soldiers. Because Toliver had been given the rank of laundress when she was first employed, her efforts to win a nurse’s pension in 1897 were fruitless."2

One of the largest field hospitals in the area was the Smoketown Hospital. Dr. W.R. Mosley, Assistant Medical Inspector, visited several field hospitals in the area. His report mentioned “seven washers, 31 cooks, bakers and water carriers.” Most likely the washers were women (and possibly the cooks and bakers). Dr. Mosley wrote, “There are several tents used by the ladies, who represent private charities in Philadelphia, where cooking and preparing food for the sick is done by the sanction of the doctor in charge." Even in a field hospitals, apparently the upper and middle-class women from Philadelphia were housed separately from the washer-women and others involved in manual labor.

Daughters of Charity

Another group of women who assisted in field hospitals and comforted the wounded and dying were the Daughters of Charity, a Catholic religious order based in Emmitsburg, Pennsylvania. "When she first became involved in Civil War relief, Sister Matilda was sixty- two years of age… She left an extraordinary first-hand account of the Sisters’ service at Harpers Ferry, Winchester, Frederick, Antietam, Boonsboro and Gettysburg."3 She wrote,

The General in charge of Maryland movements, requested the people to aid the fallen prisoners, as Government provided for the North, and would have done for all, but had not enough…Our good Superiors, with the people of Emmittsburg, collected a quantity of clothing, provision, remedies, delicacies and money for these poor men…And our Overseer drove our carriage to the place, with Father Smith C.M. and two Sisters…Our wagon of supplies bore us company, we reached the town by twilight…Two officers of the Northern Army seeing our cornettes, by the lighted lamps shining on our carriage, one said to the other: “Ah! there comes the Sisters of Charity, now the poor men will be equally cared for — no more partiality now.”

Sister Matilda detailed her journey and the conditions on the way to the battlefield. “We passed houses and barns occupied as Hospitals…fences strewed with bloody clothing…further on lay the wounded of both Armies, still on the ground, except some straw for beds, with, here and there a blanket stretched by sticks driven in the earth at head and feet of the poor man, to screen him from the burning sun.”

Photo Courtesy, Daughters of Charity Provence of St. Louise, St. Louis, MO.

In addition to providing material comfort to the soldiers, the Sisters also provided spiritual comfort. Father Smith directed the Sisters to start baptizing dying soldiers who requested it as he was overwhelmed by the sheer number of casualties. She told the story of a Union flag bearer who lay dying in a field hospital. The unnamed flag bearer’s officer called the Sisters back several times as the soldier’s condition grew worse. The officer told them, “I fear he is dying, come to him, he had been so valiant, I wish to let his wife know that the Sisters of Charity were with him in his last moments.” While attending the funeral of the flag bearer, the Sisters and Father Smith encountered General McClellan on the field. Sister Matilda wrote:

We saw, perhaps two hundred officers on horseback, war equipped, galloping towards us. A few of them, approached us nearer, all taking off their caps and bowing — one said: “I am General McClellan, and, I am happy and proud, to see the Sisters of Charity with my poor men, — how many are here?” We said: “Two, General, we came to bring relief to the sufferers, and we return in a day or so.” — “Oh!” he replied, “why can we not have more here? I would like to see fifty Sisters ministering to the poor sufferers — whom shall I address for this purpose?” Father Smith gave him the address. — He then said: “Do you know how the brave standard bearer is doing?” We told him it was his funeral we were attending.4

During her visit to Sharpsburg Sister Matilda described being in danger, especially from unexploded shells. She wrote that farms were converted to field hospitals, fences were burned for firewood, all livestock was gone, attempts had been made to burn piles of dead horses, and in the fields, long raised mounds indicated where soldiers from both sides had been buried in mass graves. Several hundred Daughters of Charity would continue to aid both Union and Confederate soldiers for the duration of the war. “The Sisters of Charity assisted surgeons during gruesome operations, and treated all forms of wounds and disease, including typhoid, smallpox and measles outbreaks. Sisters served on battlefields, in ambulances, on transport ships, in camps, in prisons, and in 32 military and civilian hospitals. ‘Their records list the sisters’ accommodations as hospitals, prisons, barracks, fields, tents and ‘improvised.’”5 The sisters faced anti-Catholic bias during their work, but they continued to help the wounded and dying of both sides during the war.

Conclusion

The Battle of Antietam and the Civil War changed the lives of many women, bringing them outside the sphere of home and domestic work. Upper-class women volunteered their time in ladies’ aid societies, sanitary fairs, and in hospitals. For some, “Necessity forced many women to…fill positions left vacant by men who had gone off to fight during the Civil War. Women took on the roles of teachers, office workers, government workers, and store clerks.6 While women were still discriminated against both during and after the Civil War, changes in technology, industrialization, efforts to give women and other marginalized groups civil rights, and society’s changing attitude towards race and gender would eventually bring women outside the house and into society, especially into the 20th century.

Citations

1 Pryor, Elizabeth B. Clara Barton: Professional Angel. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989). p. 99 from original source "Miss Barton's Lecture," Jersey City Evening Journal, April 3,1868.

2 Schultz, Jane E. "The Inhospitable Hospital: Gender and Professionalism in Civil War Medicine." Signs 17, no. 2 (1992): 363-92. Accessed June 12, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/3174468.

3 McNeil, Betty Ann D.C. "The Daughters of Charity as Civil War Nurses, Caring Without Boundaries," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 27 : Iss. 1 , Article 7, 2007. 153.

4 Coskery, Sister Matilda. Civil War Annals, Sister Loyola Law, DC, editor-transcribed 1904. Folder title “Civil War Annals by Sr. Loyola Law, DC - Containing Services of the Sisters Near Various Battlegrounds of the South; Harper's Ferry, VA; Richmond, VA; Manassas; Antietam; Boonsboro and Sharpsburg; Satterlee Hospital and West Philadelphia; Natchez, MS; Charity Hospital, Marine Hospital, NO; Alton, IL; St. Ann's Military Hospital; Richmond Infirmary, St. Francis de Sales Infirmary, Richmond, VA.” Daughters of Charity Provincial Archives, Emmitsburg, MD.

5 Coon, Kathleen E. 2010. “The Sisters of Charity in Nineteenth-Century America: Civil War Nurses and Philanthropic Pioneers.” Master’s thesis, Indiana University. 108-109. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/2185.

6 Cruea, Susan M., "Changing Ideals of Womanhood During the Nineteenth-Century Woman Movement" (2005). General Studies Writing Faculty Publications. 1. Accessed December 12, 2019 https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/gsw_pub/1.