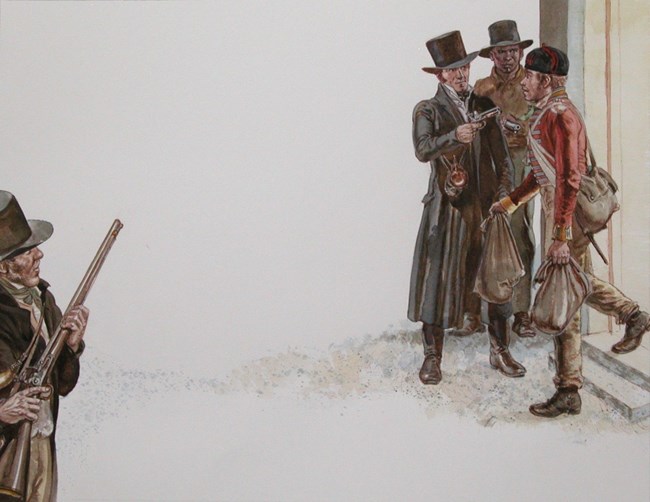

This little-known incident led to a chain of events that put Francis Scott Key among the British ships bombarding Fort McHenry. As a result, Key created new lyrics to a popular song that later became the US national anthem. (c) Gerry Embleton

It all began with an arrest. Sixty-five-year-old Dr. William Beanes of Upper Marlboro was a respected physician and Revolutionary War veteran well known in the Washington region. He had cordially entertained both Major General Robert Ross and Rear Admiral George Cockburn when the British Army had marched through on its way to attack Washington. The trouble began when the British were returning to their ships. Enemy stragglers and at least one deserter were looting in the neighborhood and Dr. Beanes helped local citizens arrest the troublemakers. The British brass was not amused by what they considered a betrayal. Dr. Beanes, arrested while in his bed, soon found himself and two companions in irons onboard a Royal Navy ship. The next stop might be Halifax, Nova Scotia, or, even worse, Dartmoor Prison, England. Richard West, a close friend of the doctor’s, hurried off to Benedict to plead for Beanes’s release, but his efforts were rebuffed. West then approached his brother-in-law, the influential young Georgetown lawyer, Francis Scott Key, for assistance. Born in Frederick County, Key, a pious man who had considered becoming an Episcopal priest, had attended St. Johns College in Annapolis. He was well connected in the Federal City. A member of the D.C. militia, he had served as a civilian aide at the Battle of Bladensburg. Key met with President Madison, who then met with Brigadier General John Mason, the commissary general of prisoners. They approved a mission to seek the release of Beanes and requested that American Prisoner Exchange Agent John Stuart Skinner accompany Key. Skinner had conducted many dealings with the British and was familiar with the commanding officers. After obtaining letters from British wounded attesting to the good treatment they had received at Bladensburg, Key met Skinner in Baltimore where they boarded a truce ship and sailed south to the British fleet near the mouth of the Potomac River. Boarding Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane’s flagship H.M. ship-of-the-line Tonnant, the party was greeted coldly by the senior British officers when the purpose of their mission was revealed. At first General Ross was unwilling to release the doctor, but when shown the letters from wounded Englishmen lauding their medical treatment, the general and his naval colleagues agreed to let Beanes go. However, the doctor and the truce party were detained to prevent them from reporting the British plans to attack Baltimore, which they had been privy to. As the enemy fleet traveled north up the Bay, the three Americans were transferred to the H.M. frigate Surprise and their truce boat and crew towed behind. Before the battle commenced, Key, Skinner, and Dr. Beanes were returned to their truce boat but still kept under guard; there they unwittingly found themselves at the very center of the Battle for Baltimore.

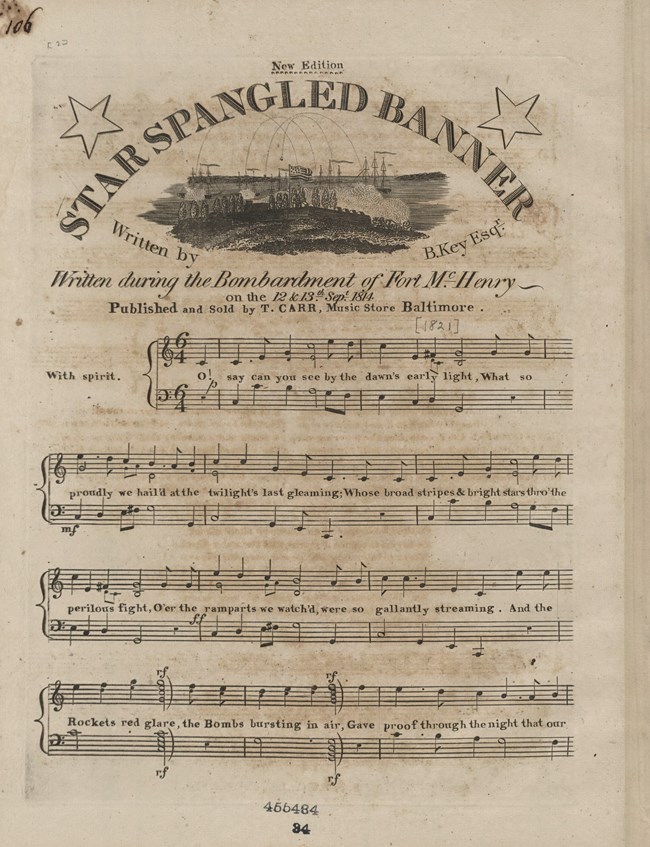

Because of its great size, the flag needed to be spread on the empty malt house floor of a nearby brewery for assembly by Pickersgill and her helpers. (c) Gerry Embleton Key and his colleagues had perhaps the most unique location from which to observe the bombardment among all Americans since they occupied front-row seats amongst the enemy as the drama unfolded. First, on September 12, they heard the guns of the Battle of North Point a few miles away. On a gloomy, rainy September 13, they watched the bombardment of Fort McHenry many miles away. All day and into the dank, stormy evening, the noisy light show of rockets and bombs continued. During the night and early morning hours of September 14, there was more intense gunfire near the fort. At dawn, the men were all straining to see the fort and the flag. The British stopped their bombardment and an eerie quiet settled over the harbor. The three Americans slowly realized the British were retiring. The attack was over. Released a few hours later as the British fleet sailed away, Key spent the evening at the Indian Queen Hotel in downtown Baltimore. It is there that he wrote the four stanzas to a tune that he probably had dancing in his brain on the truce ship. That original manuscript, entitled “The Defence of Fort M’Henry” and written with only a few revisions, is on display today at the Maryland Center for History and Culture. From the beginning, Key intended for the stanzas to be sung to “The Anacreontic Song” or “To Anacreon in Heaven,” an eighteenth-century English club song that was already popular in America. An amateur poet and avid member of the gentlemen’s clubs of the era, he had been toying with both patriotic ideas and various tunes, but his witnessing of the bombardment inspired him to write new lyrics to an old tune.

Set to the tune of a familiar club song of the day, "To Anacreon in Heaven," it proved to be very popular from the beginning and spread throughout the country in just a few weeks. Library of Congress, Music Division By September 17 printed versions of the piece were being handed out to the men in the fort and among the citizens of Baltimore. Within weeks it was published with its new name, “The Star Spangled Banner,” in seventeen newspapers all over the east. A Mr. Harding is credited as the first to formally sing the new lyrics to the song on stage before a seated audience at the Holliday Street Theatre in Baltimore on October 19, 1814. |

Last updated: April 6, 2023