|

The River of Sorrows: The History of the Lower Dolores River Valley |

|

CHAPTER TWO

"RANCHING AND FARMING IN THE LOWER DOLORES RIVER VALLEY"

Linda Dishman

Prologue

Permanent settlement of the Dolores River Valley in southwestern Colorado occurred relatively late in the State's history, awaiting the arrival of the railroad and removal of the Ute Indians. Assured of easy access to lumber and the fuel necessary for survival and guaranteed cheap, reliable outlet for products, settlers first began ranching in the valley in the late 1870's. The area experienced a short-lived second growth of economic activity in 1924 with the construction of the lumber company town of McPhee. Restricted by the narrow valley, ranching was destined to remain small scale and family operated.

Homesteading in the Lower Dolores River Valley

The history of ranching settlements within the Lower Dolores River Valley, Colorado was a microcosm of the Western frontier experience. Cattlemen first settled this area, risking attack by local Ute Indians and facing severe isolation. Restricted by the narrow valley, ranching was destined to remain small scale and family operated. The valley and surrounding grasslands which attracted the first pioneers remained the focal point of community existence, even as open rangelands diminished and became regulated. Although local struggles between cattle, sheep and farming interests existed, they never reached the magnitude of other Western settlements. Self sufficiency, a common element of the pioneer experience, remained a dominant theme throughout the history of ranching in the Lower Dolores River Valley due to isolation and other geographical constraints.

Awaiting the arrival of a dependable transportation network and subjugation of the Ute, Southwestern Colorado developed ten to twenty years later than the rest of the state. In 1880, a treaty was signed between the United States government and the tribe establishing a local reservation. Although treaty provisions required all Utes to live on the reservation, many Indians rebelled and did not immediately settle upon the assigned lands. [1]

Establishment of the Ute Reservation coincided with much regional and national publicity concerning the agricultural potential of the nearby Montezuma Valley. [2] Various state and private publications promoted the free natural grasslands and mountain ranges of the area, hoping to entice cattlemen who had overstocked ranges in eastern Colorado and nearby Western states. [3] Although this propaganda proved attractive to many, the lack of an easily accessible market inhibited growth. The establishment of mining settlements at Rico and Telluride, Colorado, however, created a steady local market and induced more people to settle in the Valley.

Settlement of the Lower Dolores Valley began slowly and continued at that pace with only minor deviations. Cattlemen were the earliest homesteaders, arriving in the mid-1870's. The history of ranching and settlement within the area can roughly be divided into four periods, each influenced by technological or economic factors. [4] The first settlers, 1875-1891, encountered rich grasslands and severe isolation. The coming of the Denver and Rio Grande Southern Railroad to Dolores in 1892 marked the beginning of the second period of settlement, 1892-1928, which ended with the nearby McPhee Lumber town's peak year of productivity. Ranching during the third period 1929-1945, experienced the bust and boom cycle of the Great Depression and World War II. The final period, the end of World War II to the present reflected the transition of ranching from a family-run business to agribusiness.

With few exceptions, the ranches of the Lower Dolores Valley remained at subsistence levels, buoyed by times of prosperity and often decimated by periods of economic stress. Self-sufficiency was a major characteristic throughout all four periods, with families supplementing their diets with vegetables grown in plots often located behind the main house.

Since the ranchers struggled to gain a marginal existence from the land, fluctuations in both nationwide and local demand for livestock and produce exerted a great effect. In addition, the availability of marketable ranch products was influenced heavily by weather and technological advances in farming techniques. Finally, the role of the government, both in dispersing land and regulating the use of the public domain, was a major, though often subtle factor in the growth and/or stagnation of ranching within the Valley.

Period 1 Homesteading (1875-1891)

Public lands in the Dolores River Valley were surveyed and opened for homesteading in the mid-1870's. Utilizing the 1820 Land Act and the 1862 Homestead Act, early settlers received patents of 160 acres within the narrow confines of the valley. Assured a constant and reliable source of water, cattlemen quickly secured the best lands along the river bottom, thus ensuring their homesteads the highest survival rate. [5]

Cattlemen were the first permanent settlers in the Lower Dolores Valley. Beginning usually with a small herd, the early settlers faced a life of hardship and isolation. Although most measureable wealth was in the form of cattle; ranchers also trapped beaver, mink and muskrat, their efforts often providing more actual cash than the growing herds. [6] Early ranchers also worked at nearby mines and on railroad and canal construction to supplement their incomes. The Kuhlman brothers, for example, settled at the north end of the Valley and worked at the mines in nearby Rico and Telluride during the winter when their ranch required less attention. [7]

Getting supplies was a common problem through the early years and snow shoes were often the only method of travel in winter months. Record snows occurred in the winter of 1886-87 and it was not unusual for the mountain passes to be closed for at least three months out of the year. Although flour and coffee were often in short supply, wild and domestic meat was abundant. In addition to cattle, most ranches raised hogs and chickens. A few dairy cows were usually kept and wild game provided variation to the rancher's diet.

The range cattle industry generally prospered in southwestern Colorado due to rich grasslands. The Dolores River Valley was no exception. Grasses in this area retained their nutriments when cured naturally. As a consequence, cattle gained weight on the open range throughout the year. In the early years of open range, a quartersection of grassland could support five to six head of cattle and as grasses became overgrazed, more virgin grasslands were simply found. [8]

Small entrepreneurs, who did not have the financial backing of Eastern and European businessmen as did many other Western Cattle concerns, developed the cattle industry in the Dolores River Valley. Early local cattle herds were composed of Longhorn steers from Texas. Tough and wiry, the Longhorn was gradually upgraded by Shorthorns in the 1870's and the Hereford in the 1890's [9] Both of these breeds could also survive the high altitudes and severe winters, and provided a higher quality product. The cattle wintered on the ranges to the west along the Colorado-Utah border and summered in the Upper Dolores Valley along the many tributaries. The ranches provided a home base for all grazing activities, as they were located midway between the two ranges.

The growth of the local cattle industry was dependent upon transportation to distant markets. When the railroad came to Durango in 1881, Dolores River Valley cattle were driven to the bustling town for shipment to Denver and St. Louis, [10] In 1881-1882 a road had been surveyed and partially built between Rico and Big Bend, but not until the 1888-1889 silver strikes in Rico, was enthusiasm sufficient to finish the road. [11] The mining activity at Rico and Telluride stimulated the first economic boom for the Valley. Cattle could now be driven to the towns where a market for beef and fresh produce was high without major weight loss.

Apprehension of Indian attack constituted a pervasive element of the pioneer's lifestyle forcing them to group together or, conversely, abandon their homes during times of tension with the Ute. Even though the Ute had been placed on a nearby reservation, they often hunted outside its boundaries. Occasional skirmishes broke out between the Anglo-settlers and Ute who often killed branded steers instead of wild game. [12] Richard May, a prominent early rancher, confirmed many local settlers' fears of Indian attack when he was killed with two other men in a raid by members of the Ute tribe in 1881. [13] The Kuhlman brothers, members of another local pioneer family, often deserted their log cabin fearing Indians would burn the structure while they slept. Their fears were realized on several occasions when their cabin was burned during the winter seasons while they lived at the mines. [14]

|

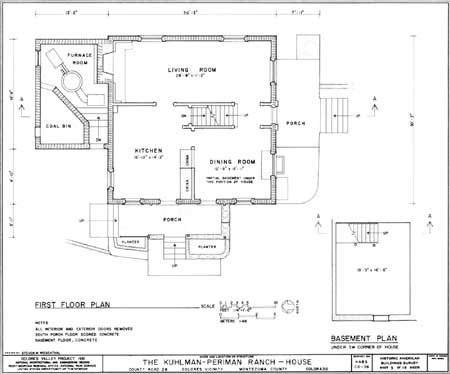

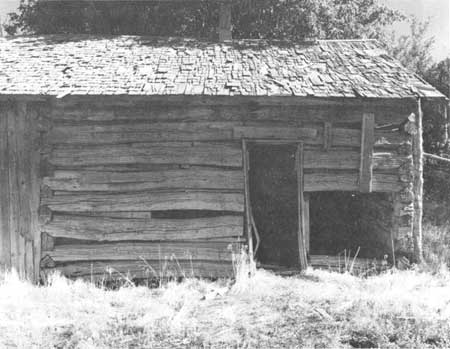

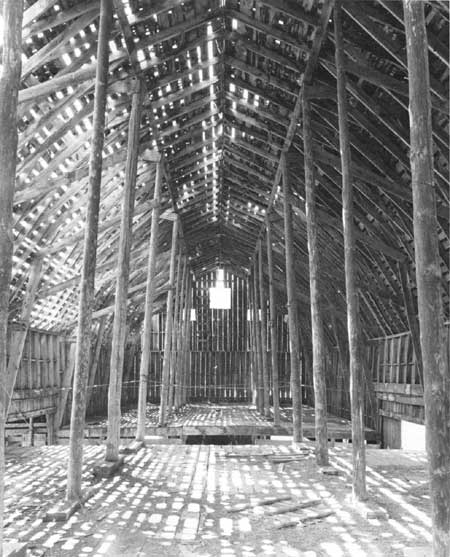

| Primitive, yet practical, diamond notched log structures such as this at the Kuhlman ranch were replaced with more elaborate and permanent frame, masonry or stone structures as soon as funds permitted. (Jet Lowe, HAER) |

Although most of the early local ranchers raised small herds of cattle, Charlie Johnson proved a notable exception. In 1880, Johnson arrived in the Dolores River Valley with one to two thousand head of cattle and several race horses. Johnson raced horses in Denver, Chicago, Coney Island and Saratoga. In 1885, one of his thoroughbreds, Jim Douglas, broke the mile world record. By 1900, Johnson had acquired 800 acres of land through purchase and homesteading, making him one of the largest landowners in the Valley at that time. [15] He became an important local politician, serving as the first mayor of Big Bend. The town of Big Bend was an important social and economic focus for early ranching activities until the town was moved to Dolores in 1892.

Cattle provided the initial means to settle the Valley but agriculture soon became an important subsidiary activity. Most early farming began at subsistence level with only limited sales of grain and produce to Rico and Telluride [16] Timber and sage had to be cleared from the land with a grubbing hoe pulled by a team of horses before cultivation could be undertaken. [17] The early farmers began operations without full knowledge of the land and its resources. Experimentation was common in the first attempts to determine which crops would prosper at high arid elevations. [18] With time, simple irrigation systems were developed, diverting water from the Dolores River to the fields through a variety of earth ditches.

Prosperity marked the first era of homesteading. Although geographically isolated from the rest of the region and state, transportation by road and rail developed quickly. [19] Trade with the mining camps proved profitable and provided employment to supplement the incomes of ranchers. Diversification of livestock and crops as well as self sufficiency were established as important themes within the valley.

|

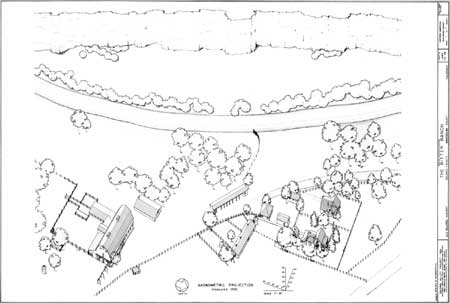

| August Kuhlman died in 1926 and shortly thereafter the operation was purchased by Albert Seeger. The Periman brothers, Tillman and Reuben, acquired the property in 1932 and added dairy cows to their cattle herd. The cattle barn was typical of similar structures in the valley with its frame shed added later to the original log barn. |

Period 2 Homesteading (1892-1927)

Due to political, geographical and economic considerations, the Denver and Rio Grande Southern Railroad bypassed Big Bend, thereby shifting the community focus of the Valley to the new town of Dolores, one and a half miles up river. Pragmatic merchants simply moved to the new townsite and the original townsite soon reverted to grazing lands. The railroad provided easy access to regional and national markets which dramatically boosted production of local ranches. Dolores became a shipping point for the Four Corners cattle industry extending as far west as San Juan County in Utah. [20] Agricultural activity increased, and sheep were first introduced on local ranges during the period.

Homesteads of this era consisted of slightly smaller acreage as new settlers found less desirable lands to patent. While livestock continued as the primary activity within the Lower Dolores River Valley farmers from Kansas and Eastern Colorado began dry farming lands around the valley producing conflict and controversy. Dry farming soon became almost continuous from the San Juan River to Groundhog Reservoir, necessitating the end of unrestricted "open" cattle grazing. [21]

Wheat constituted the major cash crop of this era and county-wide productivity was high, given the comparatively small amount of acreage. In 1898 the Dolores Flour Mill was established producing a flour named "The Pride of Dolores." The availability of local processing accelerated valley cultivation and several years later William May and Charlie Johnson built a second flour mill in Dolores. [22]

The rise of wheat as a major agricultural crop was probably due to new dryland farming techniques introduced at the turn of the century. Plowing twelve to fourteen inches deep and harrowing after each rainfall enabled farmers to retain enough moisture in the soil. Although grain was easiest to grow with this method a combination of cash and forage crops became necessary for long term success. Crop rotation was important and the cultivation of alfalfa provided not only feed for cattle but returned necessary nutriment to the soil. Agricultural publications of the era suggested keeping hogs, chickens and dairy cows to supplement dry land farming since the first years did not often pay and a good harvest was always dependent upon the weather. [23]

Dryland farming enthusiasm resulted in the introduction of two important cash crops, pinto beans and potatoes which increased the variety of cultivation within the Valley. Pinto beans yielded a high return and could be grown without irrigation. [24] The beans were planted in June and harvested between September and October. Neighbors assisted one another in the harvesting process.

Increased agricultural activity only augmented the serious problems facing cattle ranchers. The open grasslands that had once nurtured growing cattle herds rapidly diminished due to overgrazing and the encroachment of farmers and sheep ranchers. Cattle populations also declined along the Dolores River during the mid-1890's reflecting the national decline in productivity resulting from the Panic of 1893. [25]

Changes in cattle marketing also occurred. Prior to the turn of the century, steers were not sold until they reached four to five years and weighed 1,400 to 1,600 pounds. Demand for higher quality beef and the introduction of custom feeding lots prompted ranchers to begin selling steers eighteen to twenty-four months of age and 1,050 and 1,250 pounds in weight. The establishment of custom feed lots began with the rise of the Colorado sugar beet industry. The tops of the sugar beet plants were found to be an effective fattening medium, producing a higher quality of meat in a shorter quantity of time. [26] By the turn of the century, ranching in the Lower Dolores Valley involved smaller herds of fenced, high quality beef. Cattlemen had found that 100 head were needed to make a living and 1,280 acres were necessary to support a herd of that size. [27] Reduced rangelands forced cattlemen to grow alfalfa and other forage crops to feed cattle during the winter. With cultivation now needed to support cattle, ranchers could no longer raise as many head, forcing them to raise higher grades of cattle which required closer supervision. [28] The purchase of registered and high grade bulls increased at this time, as ranchers upgraded existing herds. Those cattlemen who failed to adapt to the changing situation were often forced out of business. [29]

|

| Diversification, both in livestock and agriculture, helped the prosperous Ritter Ranch survive the Great Depression. (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| William May's original log house was incorporated in the structure that now is the main house. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Similar economic factors soon encouraged the gradual introduction of sheep into the Dolores Valley. Sheep could graze on winter ranges and depleted grasslands that could no longer support cattle. In addition, between 1908 and 1914 national meat consumption spiraled downward lowering the price for cattle. [30] Sheep producers felt the resulting "pinch" from low meat prices combined with high wool prices would enable them to survive. The two 'crop' advantage of sheep eventually forced many cattlemen throughout the West to grudgingly integrate sheep into their herds.

H.F. Morgan, a local cattleman, brought the first large herd of sheep into the Lower Dolores River Valley precipitating an early sheep/cattle conflict. In 1910 Morgan went to market intending to purchase cattle and instead returned with 3,000 head of sheep. Cattlemen who had been Morgan's friends killed 40-50 of his sheep, cut tent stakes, and scared his herders to demonstrate their feelings of his new livelihood. [31] Yet this violence was relatively minor compared to other Western settlements. The ideological rift between sheepmen and cattlemen, however, continued locally for many years.

Raising sheep was a cyclical process much like cattle ranching. The Cline family, descendants of Morgan, drove flocks a short distance to the Hovenweep ruins for five winter months. In May, the sheep were driven to nearby Sagehen Flats for lambing until mid-June. Large operations "lambed" out in the open but smaller herds acquired sheds since the profit margin was slimmer. After lambing, the sheep were driven to the high cool ranges of the Upper Dolores River Valley to produce a dense growth of fleece. [32] Between September 15th and October 1st, lambs were driven to "Lizard Head" to be shipped to market. The remaining sheep were herded to Sagehen Flats before beginning the cycle again. [33]

|

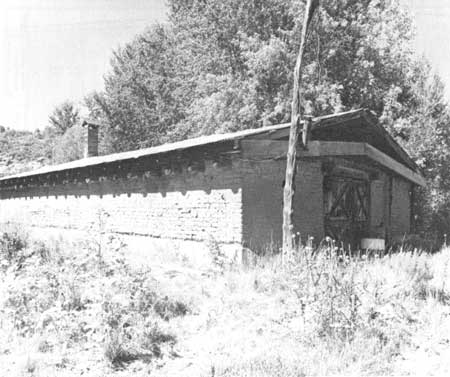

| The Ritter Ranch was fairly self-sufficient with its large collection of livestock and variety of cultivated crops. Wild hay, alfalfa, small grains, and potatoes were grown on the 70 acres of valley land and pinto beans and wheat cultivated on the west valley wall. This rectangular potato shed was built of adobe walls and covered with a sod roof. (Jet Lowe, HAER) |

Unlimited grazing resources established the premise for western cattle and sheep industries. Traditionally, as ranges became depleted, ranchers moved to virgin territory. Since settlement of southwestern Colorado occurred historically late, when the impending scarcity became apparent, few new rangelands remained. The limitation resulted in the formation of local cattlemen's associations in the 1880's and 1890's to seek solution to the grasslands dilemma. However, since most grazing was on public lands, government involvement was needed.

In 1891 the Federal government expanded its commitment to conservation of the country's natural resources with legislation creating Forest Reserves. Effective controls within the Reserves, however, were slow in development and it was not until 1906 that grazing fees were collected. A year earlier, the Montezuma Reserves were created; previously local ranchers had grazed cattle here without a fee. The government saw itself as a regulatory agency providing the greatest good over the longest period of time rather than expediting short term gain. The grazing fee for cattle was 25-30 cents per head and 5-8 cents per head for sheep. [34] The fees collected were used to upgrade the grasslands, monitor forest fires and reduce diseases with dipping tanks and vaccines provided by the United States Forest Service. [35]

|

| The Ritter barn, originally with an attached octagonal silo, was constructed in 1918 with wood from nearby Lost Canyon. The Ritters raised registered Hereford cattle as well as registered Hampshire and Suffolk sheep. (Jet Lowe, HAER) |

|

| Although time has taken its toll, the interior of the barn remains impressive. (Jet Lowe, HAER) |

Regulation of National Forest lands alleviated some of the rancher's concerns but forces outside the Valley began to exert a more powerful influence due to increased reliance upon the national market. World War I and its increased overseas market for beef had a buoying effect upon local lifestock production. Cattle and sheep prices zoomed upward and ranchers responded by increasing their herds and holdings. [36] Sheep stockyards in Denver doubled their business in one year, making Denver one of the largest markets for sheep in the world. [37] The boom gradually leveled off but the number of livestock continued to increase. The 1916 drought followed by a long cold winter left many ranchers near ruin. The sheep industry recovered within a few years but many cattlemen had over-extended themselves and entered the Great Depression in a poor financial state.

The lumber town of McPhee proved to be the saving grace for many local ranchers. Construction began in 1924 and the 600-1,000 townspeople had a positive effect upon the local economy. A reliable market in McPhee cushioned the effects of wildly fluctuating 1920 livestock prices. The Seegers, for example, located directly south of McPhee, remained in business and enlarged their dairy operation due to McPhee business. By 1938 their herd of Holstein-Friesan cows was ranked eighth in the nation. Local ranchers supplied McPhee with milk products, eggs, produce and meat, both to individual residents and to the company commissary.

|

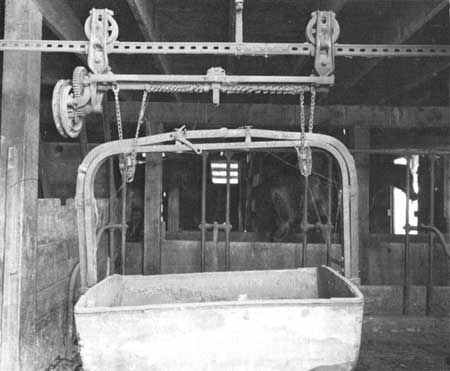

| The Ritters were often the first to incorporate "modern" technologies leading the way for surrounding ranchers. One such innovative feature of the ranch was this small metal manure car which was conveyed along a track suspended from the barn's ceiling and extending along the north side of the stalls to the exterior where it was supported by three posts and beam bents. (Jet Lowe, HAER) |

Period 3 Homesteading (1928-World War II)

The national economy exerted its strongest influence in the Dolores River Valley during this era. The Great Depression decimated livestock prices and prompted the migration of many people from Oklahoma into the narrow valley. Even though the depression had an inhibiting influence on agriculture and ranching throughout the country, the Lower Dolores Valley was somewhat insulated due to local demands created by the town of McPhee and technological advances in farming and ranching.

Homesteading activity increased during the 1930's within the River Valley. Most of the land patents occurred between 1936 and 1940, suggesting that settlement occurred early in the 1930's, with the homesteaders waiting 5-10 years to "prove up" their claims. Federal legislation passed during this time also encouraged settlers to expand and consolidate their holdings.

A majority of the new homesteaders came from the Dust Bowl areas of Oklahoma and Western Texas. Forsaking their homes, these people sought refuge in agricultural areas throughout the West. Since lands were available for homesteading within the Valley, many settled hoping to realize a livelihood from ranching. Adaptation and determination were needed to survive on these lands as they lacked fertile soil. Leslie Reynolds, who homesteaded land in the north end of the Valley, exemplifies this type of settler. On his hilly forty acres he raised goats, hogs, chickens and cultivated a small vegetable garden. [38]

In addition to attracting an influx of settlers into the Valley, the Great Depression exerted a severe effect on established ranchers. The cattle market almost collapsed and marketable livestock remained on the farms because prices and demand were low. Four to five year old mature steers sold for two to three dollars a head, when and if a buyer could be found. [39] Keeping marketable livestock on the ranch increased the drain upon an already strained local economy.

The summer of 1934 proved to be the bottom to which the local livestock industry could fall. Range water was so scarce from repeated droughts, that ranchers were forced to sell cattle and sheep to keep them from dying on the range. On August 6th of that year, the Federal government began a weekly quota purchase system for both cattle and sheep to help alleviate the situation. The government bought approximately 300 head of cattle and 1,000 head of sheep the first week of the relief program. [40]

|

| The Ritter Ranch—Barn. (clck on image for a PDF version) |

|

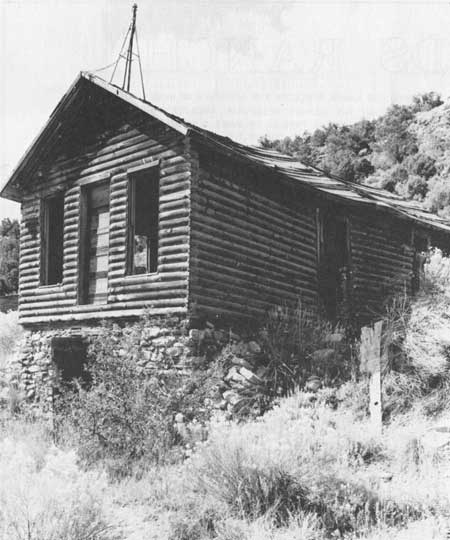

| Simple in design, the ranch was homesteaded by Leslie Reynolds in 1934 who settled the land in anticipation of his retirement from the nearby town of McPhee. (clck on image for a PDF version) |

The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 was one of a series of "New Deal" programs designed to assist the ailing livestock industry (although the origins of the Act go back to the turn of the century). The Act severely curtailed homesteading by removing unappropriated public lands from all forms of entry and then using these lands as a base for establishing grazing districts throughout the West. Under Section 7 of the Taylor Grazing Act, however, the Department of the Interior continued to allow selective homesteading providing the applicant petitioned successfully for reclassification of the land. If specialists within the Interior Department determined that the property could be used more productively as farm land than grazing land, the acreage was then re-opened for homesteading. [41]

The Act also empowered the Department of Interior with strict regulatory and maintenance authority in order to conserve and protect overgrazed rangelands. Forage resources were leased from each district for not more than ten years to holders of valid permits. [42] Ownership of lands near the ranges was required for securing permits, forcing ranchers to own land near seasonal ranges. [43] It was not unusual for ranchers to own land in at least three locations between the Utah-Colorado border and the high ranges of the Upper Dolores Valley. The Taylor Grazing Act and the Civilian Conservation Corps were called in to build retention dams and check erosion. [44] In 1938 statewide sales of ranch properties climbed to 1920 levels, indicating renewed enthusiasm in ranching as a livelihood. [45] World War II increased the demand for meat and produce, continuing the upward spiral.

Technological advances in both domestic and agricultural spheres dramatically changed the lifestyle and cultivation methods of local farmers during this era. Electricity first came to the Valley in the 1920's with the use of Delco battery systems. [46] Phone lines began to connect Valley homes with the rest of the nation by the 1930's. [47] Trucks were not common locally until the 1930's-40's as a lack of improved roads caused a delay in their incorporation into everyday life. [48] Trucks expanded local market potential and lessened dependence upon the railroad. Telephone and trucks increased contact with the world beyond Dolores and lessened the isolation that had plagued Valley settlement since its inception. [49]

The introduction of mechanized farm machinery allowed ranchers to cultivate their generally larger holdings more efficiently. Popular usage of iron wheel steam tractors to clear lands on the west side of the Valley began in the 1920's and gasoline powered tractors were common by the 1930's. [50] Bulldozers introduced at the same time, enabled ranchers to clear fields and make reservoirs to water livestock. Hay balers introduced during the early 1940's compensated for the lack of manpower during the war. [51]

Tractors made dryland farming more profitable by allowing cultivation of greater acreages and crop diversification. Although potatoes had been grown in the Dolores River Valley since the turn of the century, large scale production was not possible until the introduction of tractors. The 1930's began a heyday that continued until the 1950's as the Dolores area became an important producer of seed potatoes. [52] The local virgin meadow mountain loam yielded potatoes that were disease free, a major prerequisite for seeding. [53] Stored in root cellars on individual ranches after fall harvest, the potatoes were shipped to potato farms throughout the Southwest in spring. [54] Seed potatoes became an important local commodity not only because of their prolific cultivation but because greater demand than supply always existed and were therefore less affected by the price fluctuations of commercial potatoes.

|

| The lumber used in the construction of Reynolds home was given to him in lieu of back wages from the lumber company at McPhee. (Jet Lowe, HAER) |

Period 4 Homesteading (post World War II to the

present)

This era marked the close of the free land tradition in the Dolores River Valley. Homesteading of public lands continued until 1962 when the last patent was issued. Ranchers who wanted to enlarge their holdings secured most of these patents. The Bureau of Land Management Act of 1948 made surplus government land available and most homesteads of this period were issued under this legislation.

By the end of the Second World War, sheep had become the primary livestock in the area. [55] Cattle and dairy cows were still common on most ranches but they were small scale operations. Sheep ranchers were able to enlarge their holdings by purchasing neighboring ranch lands or obtaining additional grazing permits.

Since over half of the Colorado sheep ranches were family operations, the marginal nature of these enterprises were especially susceptible to fluctuations in market demand. [56] Synthetic fabrics which gained popular use in the 1950's and 1960's significantly decreased the demand for wool. The loss of market for both lamb meat and wool forced many sheepmen out of business. By the 1950's American wool production had dropped almost 50 percent prompting the Federal government to enact the National Wool Act of 1954. The Act supported wool prices at a level fair to both producers and consumers by subsidizing the sheepmen for the difference between production costs and sales. [57]

Although valley ranches remained family concerns, the national shift to agribusiness did have local repercussions. Increased output was needed to compete on the national market and mechanization and cultivation of larger acreages became the means to that end. Some ranches became quite large, encompassing great acreage and exerting a strong force upon the local economy. But most ranches remained the small-scale enterprises they had always been, struggling to exact a living from the rugged landscape.

As was typical in most frontier environments, neighbors and family members provided an important social and economic focus for Valley ranches. The family was an important work unit with children raising rabbits and helping in the fields. The women cared for the dairy cows and chickens while the men cultivated the fields and herded livestock. Since many of the ranches were often faced with economic crisis due to national market demands, the sale of eggs, butter and milk often provided the only real income during a season or year. Neighbors helped one another during harvest times and much socializing occurred between the ranches. Locally, little cash was used. Ranchers would exchange dairy products and eggs at Dolores stores for domestic products and meat was often bartered between neighbors.

Limited in resources, the Dolores Valley provided a challenge to determined settlers. Narrow valley walls prohibited the extensive flat acreages needed for profitable dryland farming. Due to a 1,000 foot higher elevation than the nearby Montezuma Valley, cultivation of fruit and other frost susceptible crops was not feasible. Settlers upgraded livestock and experimented with various crops in order to coax a livelihood from the land. Cooperation and technological innovation were prerequisites for success. That ranching endured more than 100 years within the Dolores River Valley attests to the adaptability, determination and self-reliance of its inhabitants.

FOOTNOTES

1Interview with Virgie LaRue, Bureau of Indian Affairs, 26 August 1981.

2Densil Cummins, "Social and Economic History of Southwestern Colorado 1860-1948," (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 1941), p. 626-627.

3Ernest Staples Osgood, The Day of the Cattleman (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1929), p. 85.

4Steven Baker, "A Brief View of Homesteading in the Primary Project Area with a Test Model of the Basic Homesteading Periods," Dolores Archeological Program, 1978, p. 54.

6Ira S. Freeman, A History of Montezuma County Colorado, (Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Publishing Co., 1953), p. 55.

7Interview with Ina Kuhlman Cline, Dunton, Colorado, 22 July 1981.

8Richard Golf and Robert McCaffree, Century in Saddle (Denver: Colorado Cattlemen's Centennial Commission, 1967) p. 144.

9Paul O'Rourke, Frontier in Transition (Denver: Colorado State Office Bureau of Land Management, 1980), p. 122.

10Freeman, History of Montezuma County, p. 57.

12Interview with Jim Cline by Linda Dishman, Dunton, Colorado, 22 July 1981.

13Freeman, A History of Montezuma County, p. 78.

14Ina Kuhlman Cline interview.

15Interview with Maurice Ribber by Susan Goulding, Mancos, Colorado, 8 September 1980.

16Bloom, "Historic Studies," Unpublished manuscript, Bureau of Reclamation Service, Dolores Archaeological Program, Cortez, Colorado 1980, p. 119.

17Joel Maxcy, "Grandad Hampton's Life and Experiences in Southwestern Colorado," unpublished paper from Dolores High School, Dolores, Colorado 1973 (typewritten).

18O'Rourke, Frontier in Transition, p. 121.

19Duane Smith, "Valley of the River of Sorrows," Unpublished Manuscript, Bureau of Reclamation, Dolores Archeological Program Files, 1978, p. 35.

20J.H. Causey, "Bond Advertisement" (Denver: no publisher, March 1911).

21Interview with Jim Cline, 22 July 1981.

22Freeman, History of Montezuma County, p. 303, 305.

23Dolores Star, 9, December 1904, p. 1C.2.

24Alvin Kezer, "Dry Farming in Colorado" (Ft. Collins, Colorado: Colorado Agriculture Experiment Station of the Colorado Agricultural Center, 1917), p. 1.

25Maurice Frink, When Grass Was King (Boulder, Colorado: University of Colorado Press, 1956), p. 116.

26W.L. Carlyle, "Bulletin on Beef Production in Colorado" (Denver: Denver Chamber of Commerce and Board of Trade, no date), p. 2.

27Goff and McCaffree, Century in the Saddle, p. 148.

28Osgood, Day of the Cattleman, p. 202.

29O'Rourke, Frontier in Transition, p. 126.

32Professor B.C. Buffum, "Improving of the Range," Western World (December 1904):12.

34Cummins, "Social and Economic History at Southwestern Colorado," p. 704.

35Ora Brooks Pecke, Ph.D., The Cattle Range Industry (Glendale, California: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1937), p. 89.

36Goff and McCaffree, Century in the Saddle, pp. 160-161.

37Denver Post, 31 December 1935, p. 10B, c.1.

38Interview with Floyd Reynolds, 21 July 1981.

39Interview with Newel Periman, Cortez, Colorado, 16 July 1981.

40Freeman, History of Montezuma County, p. 307.

41Rourke, Frontier in Transition, p. 145.

43Cummins, "Social and Economic History of Southwestern Colorado," p. 707.

44Farrington Carpenter, "Range Stockmen Meet the Government," 1967 Denver Westerner's Brand Book, Vol. XXIII (Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Publishing Co., 1968), p. 335.

45Denver Post, 2 January 1939, p. 2A, c.5.

47Ina and Jim Cline interview.

49Interview with Art and Bill Hamilton, Dolores, Colorado, 28 July 1981.

52Dolores Star, 27 March 1981, p. 6.

53Dolores Star, 5 August 1938.

54Art and Bill Hamilton interview.

56Kerry Gee, "Facts for Western Colorado Sheep Producers," Colorado State University, Fort Collins, 1978, p. 13.

57Denver Post, 21 September 1958, p. 2AA, c.3.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

Aldridge, Reginald. Life on a Ranch. New York: Argonaut Press, Ltd., 1884; reprint ed., 1966.

Billington, Ray. Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier. New York: McMillan Publishing Co., 1974.

Freeman, Ira S. A History of Montezuma County Colorado. Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Publishing Co., 1953.

Frink, Maurice. When Grass Was King. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 1956.

Gates, Paul. History of Public Land Law Development. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968.

Gaff, Richard and McCaffree, Robert. Century in the Saddle. Denver, Colorado: Cattlemen's Centennial Commission, 1967.

O'Rourke, Paul. Frontier in Transition. Denver, Colorado: Colorado State Office Bureau of Land Management, 1980.

Osgood, Ernest Staples. The Day of the Cattleman. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1929.

Pabor, William. Colorado as an Agricultural State. New York: Orange Judd Co., 1883.

Peake, Ora Brooks. The Colorado Range Cattle Industry. Glendale, California: Arthur H. Clark Publishing Co., 1923.

Pelzer, Louis. The Cattleman's Frontier. Glendale, California: Arthur Clark Co., 1936.

ARTICLES

Carpenter, Farrington. "Range Stockmen Meet the Government" in the 1967 Denver Westerner's Brand Book, Vol. 23. Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Publishing Co., 1968.

Taylor, Fred and Robinson, Anna Florence. "Pioneering in Southwest Colorado." The Colorado Magazine. 4 (July 1935).

Vickles, W.B. "Stock Raising in Colorado 1878" in Cattle Cavalcade in Central Colorado, edited by George Everett. Denver, Colorado: Golden Bell Press 1966.

Westermeier, Clifford. "The Legal Status of the Colorado Cattlemen 1867-1887." The Colorado Magazine. 4 (July 1948).

GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS

Denver, Colorado. "Dry Farming in Colorado" by Alvin Kezer, State Board of Immigration, (no date).

Denver, Colorado. "Bulletin on Beef Production in Colorado" by W.L. Carlyle, Chamber of Commerce and Board of Trade, (no date).

Fort Collins, Colorado. "Dry Farming in Colorado" by Alvin Kezer, Colorado Experiment Station of the Colorado Agricultural Center (1917).

Fort Collins, Colorado. "Factors that Affect Sheep Income" by R.T. Burdick, Bulletin No. 467. Colorado Experiment Station, Colorado State College, (May 1941).

United States Government Land Grant Patent Records, 1881-1962. Bureau of Land Management, State Office, Denver, Colorado.

UNPUBLISHED SOURCES

Cline, Kay. "Fred Cline High School Paper, Dolores High School, Dolores, Colorado, 1973 (typewritten).

Crowley, John M. "Ranches in the Sky" Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1964.

Cummins, Densil. "Social and Economic History of Southwest Colorado 1860-1948" Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 1951.

Duranceau, Deborah. "Oral History as a Tool of Historic Archeology: Application on the Dolores Archeological Project" paper presented at the 13th annual meeting of the Society for Historical Archeology, 8 January 1981.

Fuelberth, John Herbert. "Evaluation of Selected Factors Influencing Retail Value of Lamb." Masters Thesis, Colorado State University, 1964.

Gee, Kerry. "Facts for Western Colorado Sheep Producers" manuscript, Colorado State University, 1978.

Maxcy, Joel. "Grandad Hampton's Life and Experiences in Southwest Colorado" High School Paper, Dolores High School, Dolores, Colorado, 1973.

White, Adrian to Deborah Duranceau, 23 November 1979. Bureau of Reclamation Dolores Archeological Program Files, Cortez, Colorado.

PAMPHLETS

Causey, J.H. and Co. "Bond Advertisement" Denver, March 1911.

Pyle, Harry. "Bulletin #4" Dolores, Colorado, 18 January 1941.

DOLORES ARCHEOLOGICAL PROGRAM REPORTS

Baker, Steven and Smith, Duane. Bureau of Reclamation, "Dolores Archeological Program Historic Studies—1978 Research Design, Inventory and Evaluation" 1978, Cortez, Colorado.

Bloom, John. Bureau of Reclamation "Historic Studies" 1981, Cortez, Colorado.

ORAL INTERVIEWS

Cline, Dennis and Carlene. Dolores, Colorado, interview by Deborah Duranceau December 1979.

Cline, Homa Louise. Dolores, Colorado, interview by Deborah Duranceau, 18 August 1979.

Cline, Jim and Ina. Dunton, Colorado, interview 22 July 1981.

Engels, Charles. Dolores, Colorado, interview by Susan Goulding, 8 January 1981

Hamilton, Art and Bill. Dolores, Colorado, interview 28 July 1981.

Hill, Katie. Interview questionnaire, 26 October 1979.

LaRue, Virgie. Bureau of Indian Affairs, interview 26 August 1981.

Lee, Charles. Dolores, Colorado, interview 22 July 1979.

Lucero, Joe and Mary. Dolores, Colorado, December 1979.

Milhoan, Lawana. Dolores, Colorado, interview by Deborah Duranceau, 12 September 1979.

Periman, Newel. Cortez, Colorado, interview 16, 21, 23 July 1981.

Ritter, John, Ritter, Maurice, and Tibbet, Irene. Mancos, Colorado, interview by Susan Goulding, 8 September 1980

Thomas, Inez. Dolores, Colorado, interview by Susan Goulding, 10 October 1980

Turner, John. Dolores, Colorado, interview by Sampson, 16 October 1979.

White, Adrian. Lebanon, Colorado, interview 15 July 1981.

Wilbanks, Stanley. Dolores, Colorado, interview by Deborah Duranceau, 12 December 1979.

NEWSPAPERS

Cortez Journal-HeraldDaily News

Denver Post

Denver Times

Dolores Star

Montezuma Valley Journal

Rocky Mountain News

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

river_of_sorrows/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2008