| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith At noon on 15 August 1945, people gathered near radios and hastily setup loud speakers in homes, offices, factories, and on city streets throughout Japan. Even though many felt that defeat was not far off, the vast majority expected to hear new exhortations to fight to the death or the official announcement of a declaration of war on the Soviet Union. The muted strains of the national anthem immediately followed the noon time-signal. Listeners then heard State Minister Hiroshi Shimomura announce that the next voice they would hear would be that of His Imperial Majesty the Emperor. In a solemn voice, Emperor Hirohito read the first fateful words of the Imperial Rescript:

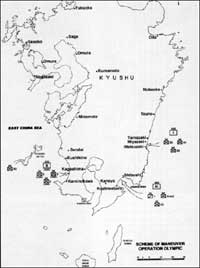

Although the word "surrender" was not mentioned and few knew of the Joint Declaration of the Allied Powers calling for unconditional surrender of Japan, they quickly understood that the Emperor was announcing the termination of hostilities on terms laid down by the enemy. After more than three and a half years of fighting and sacrifice, Japan was accepting defeat. On Guam, 1,363 nautical miles to the south, the men of the 6th Marine Division had turned in early the night before after a long day of combat training. At 2200, lights on the island suddenly came on. Radio reports had confirmed rumors circulating for days throughout the division's camp on the high ground overlooking Pago Bay: the Japanese had surrendered and there would be an immediate ceasefire. As some Marines clad only in towels or skivvies danced in the streets and members of the 22d Marines band conducted an impromptu parade, most of the 4th Marine Regimental Combat Team was on board ship, ready to leave for "occupational and possible light combat duty in Japanese - held territory." No less happy than their fellow Marines ashore, they remained cynical. The Japanese had used subterfuge before. Who could say they were not being deceptive now? In May 1945, months before the fighting ended, preliminary plans for the occupation of Japan were prepared at the headquarters of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur in Manila and Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz on Guam. Staff studies, based on the possibility of the sudden collapse or surrender of the Japanese Government and High Command, were prepared and distributed at army and fleet level for planning purposes. In early summer, as fighting still raged on Okinawa and in the Philippines, dual-planning went forward for both the subjugation of Japan by force in Operations Olympic and Coronet, and its peaceful occupation in Operations Blacklist and Campus. Many essential elements of MacArthur's Olympic and Black list plans were similar. The Sixth Army, which was slated to make the attack on the southern island of Kyushu under Olympic, was given the contingent task of occupying southern Japan under Operation Blacklist. Likewise, the Eighth Army, using the wealth of information it had accumulated regarding the island of Honshu in planning for Coronet, was designated the occupying force for northern Japan. The Tenth Army, a component of the Honshu invasion force, was given the mission of occupying Korea. Admiral Nimitz's plan envisioned the initial occupation of Tokyo Bay and other strategic areas by the Third Fleet and Marine forces, pending the arrival of formal occupation forces under General MacArthur's command. When the Japanese government made its momentous decision to surrender in the wake of atomic bombings and the Soviet Union's entry into the war, MacArthur's and Nimitz's staffs quickly shifted their focus from Operation Olympic to Blacklist and Campus, their respective plans for the occupation. In the process of coordinating the two plans, MacArthur's staff notified Nimitz's representatives that "any landing whatsoever by naval or marine elements prior to CINCAFPAC's [Mac Arthur's] personal landing is emphatically unacceptable to him." MacArthur's objections to an initial landing by naval and accompanying Marine forces was based upon his belief that they would be unable to cope with any Japanese military opposition and, more importantly, because "it would be psychologically offensive to ground and air forces of the Pacific Theater to be relegated from their proper missions at the hour of victory."

Despite apparent disagreements, MacArthur's plan for the occupation, Blacklist, was accepted. But with at least a two-week lag predicted between the surrender and a landing in force, both MacArthur and Nimitz agreed that the immediate occupation of Japan was paramount and should be given the highest priority. The only military unit available with sufficient power "to take Japan into custody at short notice and enforce the Allies' will until occupation troops arrived" was Admiral William F. Halsey's Third Fleet, then at sea 250 miles south east of Tokyo, conducting carrier air strikes against Hokkaido and northern Honshu. On 8 August, advance copies of Halsey's Operation Plan 10-45 for the occupation of Japan setting up Task Force 31 (TF 31), the Yokosuka Occupation Force, were distributed. The task force's mission, based on Nimitz's basic concept, was to clear the entrance to Tokyo Bay and anchorages, occupy and secure the Yokosuka Naval Base, seize and operate Yokosuka Airfield, support the release of Allied prisoners, demilitarize all enemy ships and defenses, and assist U.S. Army troops in preparing for the landing of additional forces. Three days later, Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger, Commander, Battleship Division 7, was designated by Halsey to be commander, TF 31. The carriers, battleships, and cruisers of Vice Admiral John S. McCain's Task Force 38 also were alerted to organize and equip naval and Marine landing forces. At the same time, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, directed the 6th Marine Division to furnish a regimental combat team to the Third Fleet for possible occupation duty. Major General Keller E. Rockey, Commanding General, III Amphibious Corps, on the recommendation of Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., nominated Brigadier General William T. Clement, the division's assistant commander, to head the combined Fleet landing force. Brigadier General William T. Clement Leading the 4th Marines ashore at Yokosuka on 30 August was a memorable event in Brigadier General William T. Clement's life and career. Clement was 48 and had been a Marine Corps officer for 27 years at the time he was given command of the Fleet Landing Force that would make the first landing on the Japanese home islands following the nation's unconditional surrender. He was born in Lynchburg, Virginia, and graduated from Virginia Military Institute. Less than a month after reporting for active duty in 1917, Clement sailed for Haiti where he joined the 2d Marine Regiment and its operations against rebel bandits.

Upon his return to the United States in 1919, he reported for duty at Marine Barracks, Quantico, where he remained until 1923, when he became post adjutant of the Marine Detachment at the American Legation in Peking, China. In 1926, he was assigned to the 4th Marine Regiment at San Diego as adjutant and in October of the same year was given command of a company of Marines on mail guard duty in Denver, Colorado, where he remained for three months until rejoining the 4th Marines. Clement sailed with the regiment for duty in China in 1927 and was successively a company commander and regimental operations and training officer. Following his return to the United States in 1929, he became the executive officer of the Marine Recruit Depot, San Diego, and then commanding officer of the Marine Detachment on board the West Virginia. Clement spent most of the 1930s at Quantico, first as a student, then an as instructor, and finally as a battalion commander with the 5th Marines. The outbreak of World War II found Clement serving on the staff of the Commander-in-Chief, Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines. Although quartered at Corregidor, he served as a liaison among the Commandant, 16th Naval District; the Commanding General, U.S. Armed Forces in the Far East; and particularly with the forces engaged on Bataan until ordered to leave on board the U.S. submarine Snapper for Australia in April 1942. For his handling of the diversified units engaged at Cavite Navy Yard and on Bataan, he was awarded the Navy Cross. Following tours in Europe and at Quantico, Clement joined the 6th Marine Division in November 1944 as assistant division commander and took part in the Okinawa campaign. Less than two months after the Yokosuka landing, he rejoined the division in Northern China. When the division was redesignated the 3d Marine Brigade, Clement became commanding general and in June 1946 was named Commanding General, Marine Forces, Tsingtao Area. Returning to the United States in September, he was appointed President, Naval Retiring Board, and then Director, Marine Corps Reserve. In September 1949, he assumed command of Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, holding that post until his retirement in 1952. Lieutenant General Clement died in 1955. The decision of which of the division's three regiments would participate was an easy one for General Shepherd. "Without hesitation [he] selected the 4th Marines," Brigadier General Louis Metzger, Clement's former chief of staff, later wrote. "This was a symbolic gesture on his part, as the old 4th Marine Regiment had participated in the Philippine Campaign in 1942 and had been captured along with other U.S. forces in the Philippines. Now the new 4th Marines would be the main combat formation taking part in the initial landing and occupation of Japan."

Preliminary plans for the activation of Task Force Able were prepared by III Amphibious Corps. The task force was to consist of a skeletal headquarters of 19 officers and 44 enlisted men, which was later augmented, and the 4th Marines, Reinforced, with a strength of 5,156. An amphibian tractor company and a medical company were added bringing the total task force strength up to 5,400. Officers designated to form General Clement's staff were alerted and immediately began planning to load out the task force. III Amphibious Corps issued warning orders to the division's transport quartermaster section directing that the regimental combat team, with attached units, be ready to embark 48 hours prior to the expected time of the ships' arrival. This required the complete re-outfitting of all elements of the task force which were undergoing rehabilitation following the Okinawa campaign.

|