.gif)

MENU

Chapter 1

Early Resorts

Chapter 2

Railroad Resorts

Chapter 3

Religious Resorts

Chapter 4

The Boardwalk

Chapter 5

Roads and Roadside Attractions

Chapter 6

Resort Development in the Twentieth Century

Appendix A

Existing Documentation

|

RESORTS & RECREATION

An Historic Theme Study of the New Jersey Heritage Trail Route |

|

CHAPTER IV:

The Boardwalk

Although the first and most renowned of its kind on the shore, the Atlantic City boardwalk is hardly representative of a typical New Jersey boardwalk. Most shore communities have built some sort of raised wooden walk running parallel to an "ocean drive," (Fig. 61) but the majority of these are without extensive amusements or concessions. Along the north shore from Ocean Grove to Spring Lake, the pedestrian walk is occasionally broken by a building; only a few communities, such as Point Pleasant and Seaside Heights, make boardwalk amusements a central feature of their cities. When an Atlantic City type atmosphere is absent, the importance of the boardwalk as a recreational and social space seems to increase. Such "community" boardwalks combine the experience of a rapidly moving bikepath with that of a more private park. Research on the history of American resorts, particularly Coney Island and Atlantic City, has not resulted in a comprehensive study of the boardwalk. A thorough history of this urban form that considers social and economic functions in the context of hotels, casinos, and amusement piers remains to be written.

|

| Figure 61. Boardwalk and beach, Asbury Park ca. 1905. Library of Congress. |

Atlantic City: the First Boardwalk

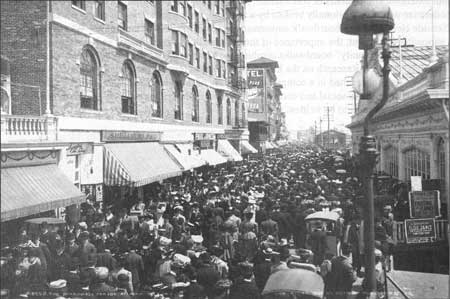

Written accounts of Atlantic City from the 1920s-30s describe a boardwalk more similar to a modern strip development than a pedestrian walk. As wide as a four-lane highway, the boardwalk was a collection of flashy signs, lights, and products that must have seemed particularly urban during the first years of the automobile (Fig. 62). Today, the boardwalk has become sedentary in comparison to its fast-paced gambling casinos and offers fewer shops than the local mall. The Garden State Parkway, since 1956 the main route along the shore, has done away with roads and roadside structures by separating itself from this consumer world with a dense screen of trees. The roadside architecture of the Parkway is solely tollbooths punctuated by exit signs. Our present-day nostalgia for nineteenth-century whimsy encompasses both boardwalk and roadside, the exotic place and the path to it, which together represent much that has been sacrificed in exchange for lower costs and increased efficiency.

|

| Figure 62. Boardwalk Parade, Atlantic City. ca 1890-1906. Library of Congress. |

Despite its earliest origins as a health retreat, Atlantic City's resort-based economy necessitated a wide variety of year-round attractions. The Atlantic City boardwalk, which has in many ways defined the character and success of the resort, did not originate as a purely commercial endeavor. [1] Atlantic City itself, on the other hand, was a commercial development from its conception—the joint creation of a Philadelphia-based railroad and land company. [2] The boardwalk, touted as the first of its kind, was the combined effort of hotel proprietor Jacob Keim and railroad conductor Alexander Boardman. Both were concerned with keeping sand off floors and furniture in hotel rooms and railroad cars. In June 1870, just two months after they presented the city council with a petition demanding a "footwalk," a mile-long street was constructed of boards "1-1/2" thick, nailed to joists set crosswise, 2' apart, built in sections, said to have been 12' long. [3] The boardwalk's sectional design allowed it to be moved away from threatening storm tides and packed up for the winter. Although the ordinance required that buildings be set back 30' from the walk, by 1880, when a second replacement boardwalk was completed, commercial buildings were permitted within 10'. According to the 1883 city directory, there "were fifty-two bathhouses renting rooms and swim suits, four small hotels, four guest cottages, two piers, fifteen restaurants, and many stores." [4]

The city built the second boardwalk, measuring 14' wide, but still with boards running lengthwise and still not elevated substantially above the sand. Boardwalk buildings, now permitted within 10' of the walkway (bathhouses 15'), were raised above the walk to accommodate high water. A major winter storm in January 1884 led to the construction of a more substantial boardwalk the following summer. Raised 5' above the sand and 20' wide, this third boardwalk was designed of crosswise boards. Businesses occupied both sides of the boardwalk, often enclosing the walkway. Despite the new height of the walk, the city neglected to include railings. The Atlantic Review reported in August 1885 that, "Nearly every day somebody falls off the boardwalk. In nearly every instance, the parties have been flirting." Yet another hurricane in September 1889 caused enough damage on the boardwalk to require complete reconstruction. This time the city began the long process of acquiring a 60' right of way from the state legislature to lay out a public street. The boardwalk's fourth reincarnation in May 1890 was now 24' wide and 10' high, with crosswise boards and substantial railings. Measures were taken to prevent most building on the ocean side, but it was almost a decade before all the businesses conformed to these new policies.

Atlantic City's success can be measured by the wear and tear on the boards. The need for another new promenade corresponded to a significant population increase, from 13,055 in 1890 to 46,150 in 1910. [5] The fifth and final boardwalk used property easements to complete construction by 1896. During the early 1900s, the boardwalk was extended along the eight-mile shoreline of the island, linking the new communities of Margate and Ventnor with their more renowned neighbor. The 40' wide walk had steel pilings, girders and railings. Any piers were required to be more than 1,000' long. Over the years, the fifth walk has undergone several changes; the city encased the steel pilings in concrete in 1903, extended portions in 1907, added runways to accommodate rolling chairs in 1914, and introduced a herringbone pattern in 1916. [6]

From the boardwalk's first decades of commercial use, entrepreneurs stretched their imaginations to devise new and creative ways of attracting trade and publicity. The first amusement pier was constructed in 1882 with, "the aim being to occupy little space on the boardwalk, yet to pack as much amusement behind the entrances as was physically possible." [7] The sea destroyed at least one pier as early as 1881 and another the next year. Soon the city council was more worried about the damage done to its seacoast by commercial development than the effects of storms. In 1884, the city gained control over the beach area through a special "Beach Park Act" with limitations restricting the lengths of piers. Finally, laws were enacted prohibiting all new development on the ocean side, while tacitly encouraging development across the walk. [8] Throughout the deliberations, the established piers continued to collect and display the exotic and extravagant. Applegate's Pier opened in 1884, providing music and vaudeville, a picnic area, a parking lot for baby carriages, and an ice water fountain. The 1886 Iron Pier began by offering stage shows, but in 1898 it was sold to H.J. Heinz and Company and became the famous Heinz Pier (Fig. 63). This pier established permanent displays of the company's products, and gave away free samples. After opening in 1898, the Steel Pier entertained crowds with moving pictures and orchestra concerts, while hosting national conventions and commercial exhibits.

|

| Figure 63. Heinz Pier, 1890. Atlantic County Historical Society. |

A 1928 account of the six piers—the Heinz, Garden, Steel, Steeplechase, Central, and Million Dollar—described self contained environments resembling large hotels out on the water. "They furnish concerts by famous bands, motion pictures, vaudeville, minstrels, dancing, deep-sea net hauls, and just the still and far-out watching of the waves and the moon. They also house many large conventions." [9] Pier owners tried to outdo one another in extravagance and showmanship. The 2,000' long Steel Pier entertained its public with girls on horseback who dove off 45' heights. Before 1906, Capt. John Young had spent a fortune on the Million Dollar Pier (Fig. 64) located at One Atlantic Ocean, also the address of his own three-story home. Young's Pier offered an aquarium, ballroom, and twice-daily fish haul. Today, the ballroom and the Captain's Italian villa and sculpture garden have been replaced by Ocean One, a contemporary mall with three levels of arcade amusements, shops, and restaurants. [10]

|

| Figure 64. Young's Residence on Million Dollar Pier ca. 1900-1910. Library of Congress. |

By 1900, Atlantic City had become so commercialized that even the experience of the ocean and other "natural" recreations were packaged and produced. Examining turn-of-the-century Atlantic City, Charles Funnell asserts that the ocean was essentially an unfamiliar and frightening place, a frontier or wilderness. The amusements, on the other hand, were urban in character, as was the press of the crowds. [11] The WPA Guide to New Jersey found the city to be "a glittering monument to the national talent for wholesale amusement," adding that "natural considerations are subordinated to one of the most fascinating man-made shows playing to capacity audiences anywhere in the world." [12]

WPA Guide writers stressed the centrality of the boardwalk to the Atlantic City experience—"Atlantic City is an amusement factory, operated on the straight-line, mass-production pattern. The belt is the boardwalk along which each specialist adds his bit to assemble the finished product, the departing visitor, sated, tanned, and bedecked with souvenirs." The same authors sought out the decorum of the boardwalk's commercial strip, claiming, "Architecturally the motifs are mixed, but functionally they unite in presenting a glittering, luxurious front." These writers highlighted the permanent displays of national advertisers, as well as the classy shops of the hotels' first floors. [13]

The 1928 New Jersey Chamber of Commerce compared Atlantic City's boardwalk to "the gayest thoroughfares of the world." On the boardwalk, "The vivacity and modernity of scene and action allure the eye of every visitor, and Atlantic City is encompassed by a constant holiday atmosphere." Even the chamber's attempts to play up the boardwalk's maritime dimensions paid tribute to commerce. "Unique among world institutions of this kind, the boardwalk is described as analogous to the deck of an immense ocean liner, for the impression of being far out at sea is enhanced by the many 'steamer decks' with their 'steamer chairs' at the second-story level, all overlooking boardwalk and ocean. Exhibits of merchandise and manufactured products line the miles of boardwalk. They are maintained for national advertising purposes, since people come here from everywhere." [14]

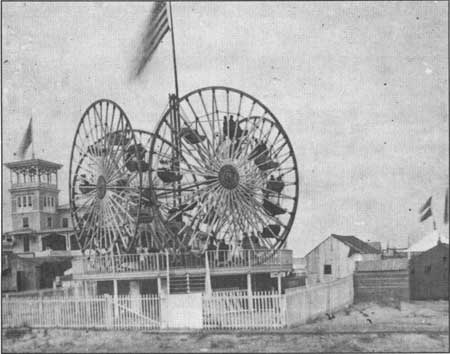

By 1878, when Harper's magazine authors wrote "Along Our Shore," the urban development of the city seemed proportional to the ever-increasing collection of spectacles lining the boardwalk. "The hotels, saloons, restaurants, and boarding cottages of all sizes are innumerable; and along the beach, which is semicircular, there are photograph galleries, peep shows, marionette theaters, conjuring booths, circuses, machines for trying the weight, lungs or muscles of the inquisitive, swings, merry-go rounds, and all the Various sideshows which reap the penny harvest of holiday crowds." [15] The early versions of the Ferris wheel that arrived in the 1870s were accompanied by merry-go-rounds and track rides resembling roller coasters. [16] Issac N. Forrester built his "Epicycloidal Wheel," (Fig. 65) four huge wheels set at right angles and each carrying eight gondolas for two people, near the Seaview Excursion House in 1872. [17] In 1887, LaMarcus Adna Thompson and James J. Griffith constructed the first scenic railway on the boardwalk, the success of which would manifest itself in their New York based business, L.A. Thompson Scenic Railway Company. The scenic railway was considered the most exciting amusement of its time and customers were encouraged to "Ride it just for fun." [18] The Excursion House advertised "the Mt. Washington Toboggan slide" around 1889, four years before another ride combining wheel and rail was promoted in the Daily Union. The reporter describes how "the passengers will shoot down a toboggan slide to a groove in the large wheel, be taken up, and "whirled around five minutes." [19]

|

| Figure 65. Epicycloidel Wheel, ca. 1870. Atlantic County Historical Society. |

While some indulged in the excitement of mechanical amusements, others preferred tranquil rides along the boardwalk in rolling chairs (Fig. 66). After several years of renting wheelchairs to invalid vacationers from his hardware store at 1702 Atlantic Avenue, William Hayday realized he could market the rolling chair for public boardwalk transportation. Since 1887, when Hayday sent his first commercial wicker chairs rolling down the walk, the rides have been an Atlantic City tradition.

|

| Figure 66. Rolling Chairs, Atlantic City. ca. 1905. Library of Congress |

At the height of their popularity, in the 1920s, only the hotels employed more workers than the rolling-chair service. Though business declined during World War II, the pastime made a comeback beginning in 1948, when the Blue Chair Company introduced a line of motorized vehicles made of sheet steel. The Shill Rolling Chair Company purchased these in 1955, and created a new version with a traditional wicker body in place of the steel hull. The new combination satisfied customers' desire for nostalgia and fascination with technological innovation, two cravings liberally indulged in Atlantic City, while virtually wiping out the manually pushed rolling chair. The traditional human-powered chair experienced a revival in 1984; Larry Belfer began offering rides from the closed Apollo Theater at New York Avenue and the Boardwalk. [20] For those seeking a more expedient trip, a thirteen-passenger jitney runs up and down Pacific Avenue and provides service to the marina district casinos. [21]

|

| Figure 67. "I could stay in Atlantic City forever" on card in woman's hand. Library of Congress. |

Salt-water taffy, indisputably one of the most famous edible boardwalk commodities, was popularized by David Bradley in the early 1880s and epitomizes the image of romantic seaside vacations. Joseph Fralinger made his fortune by packaging the candy in souvenir boxes. With his taffy profits, Fralinger constructed a theater for a trained-horse show, "Bartholomew's Equine Paradox." When the show went on the road in 1892, Fralinger remodeled the building to house the Academy of Music, the boardwalk's first real theater. [22] After further alterations in 1908, the building became Nixon's Apollo Theater. [23] Fralinger's distinctive, elongated taffy is still sold in special boxes advertising, among other scenes, the picturesque beauty of Atlantic City at sunset.

Picture postcards were also popular Atlantic City souvenirs for sale along the boardwalk (Fig. 67). According to one story, the wife of local printer Carl Voelker traveled to Germany in 1895 and brought back the European idea. Her husband marketed the postcard as an advertising tool for Atlantic City hotels. [24] Soon "view cards," purchased at boardwalk shops, such as Hubin's Big Post Card Store, became a required form of documenting the vacation experience. [25] As today, early postcards depicted a range of scenes from simple views of significant buildings to parodies of local characters.

What kinds of people visited Atlantic City to enjoy the boardwalk, hotels, and amusement piers? Charles Funnell questions the "myth" that Atlantic City was a posh destination attracting American elites, prior to a supposed decline in the 1930s. Closely associated with this myth is the belief, promoted by early publicists, that Atlantic City encouraged unusual social mixing. An 1885 tourist guide claimed that on the Boardwalk, "such a conglomeration of all classes of society cannot be seen in any other seaside resort in the world." [26] (Fig. 68) The WPA Guide to 1930s New Jersey conveyed a similar sense of turmoil with the observation, "Here Somebodies tumble over other Somebodies and over Nobodies as well." [27]

|

| Figure 68. Virginia Avenue/boardwalk, ca 1890. Atlantic County Historical Society. |

Funnell reaches two significant conclusions about the nature of Atlantic City visitors from 1875 to 1910 which challenge these assumptions. First he argues that the "bluebloods," society's elites, did not visit Atlantic City in significant numbers. Funnell distinguishes between "high society" and the "nouveau bourgeois." Using hotel registers, the social register, and newspapers, Funnell determines that the latter group was not repelled by the resort's garishness and commercialism. Second, he finds that Atlantic City appealed primarily to the lower middle class, the "lower white-collar" worker. The seaside resort offered the illusion of mobility, status, and interaction with the upper classes. Atlantic City invited the fulfillment of social aspirations, perhaps best symbolized by the popular boardwalk rolling chair. For a minimal sum, one could ride along the boardwalk, propelled by another person of lower status—usually an African-American—and enjoy the accompanying sense of privilege. In Funnell's analysis, Atlantic City was less about social mixing than about the marketing of genteel class ideals. He points out that different parts of the boardwalk were geared toward different classes of visitor groups, a fact also noted in the 1885 guide. [28]

Class segregation was equally apparent in the workforce staffing boardwalk hotels, restaurants, and businesses. Herbert Foster has documented that the vast majority of the recreation industry's workforce was black—95 percent by 1900. From 1905 to 1925, 95 percent of the hotel workforce was African-American, although a few hotels, such as the Traymore, never hired black waiters. Foster convincingly argues that the significance of black labor in building Atlantic City's success can hardly be underestimated. In 1915, blacks comprised 27 percent of Atlantic City's permanent population. At the turn of the century, whites expressed concern over the numbers of blacks in the city and the opportunities for racial mixing. African-Americans did lose ground during the early decades of the twentieth century, experiencing displacement by whites and increasing segregation; by 1932, only four or five hotels still employed black waiters. During the same years, the residential ghetto (consolidated by 1905) offered business opportunities to blacks and was the home of numerous organizations. The new school segregation opened up teaching positions to African-Americans. [29]

Racial segregation was a fact of life on the Atlantic City boardwalk. Although black servants had more freedom of movement, black tourists and hotel-recreation employees were restricted to a particular bathing area and excluded from many of the pavilions. The WPA Guide recorded that "By tacit understanding the Negroes frequent certain portions of the beach at certain hours," and mentions separate city tennis courts for blacks. [30] African-Americans sat in the balconies of the theaters and movie houses that permitted them access. Customarily, black tourists were encouraged to visit the resort at the beginning or end of the season, and if possible, off-season. Such advice was distributed through manuals like The Negro Travele'r Green Book, a listing of hotels open to black travelers organized by city and state. Readers who followed the book's instructions would avoid "encountering embarrassing situations." [31] The federal government also issued a "Directory of Negro Hotels and Guest Houses" (1941), with seven possibilities in Atlantic City and options in nine other shore resorts. [32]

The Depression hit Atlantic City hard. By the mid 1930s, the city was putting forward proposals to redesign the resort for a more wealthy clientele. The city's first slum-clearance and housing project was dedicated in 1937. By 1940, the year-round population began to decline. The federal government kept Atlantic City's businesses alive during World War II by using the resort as an Army Air Force training base; forty-seven of the biggest hotels were filled in this manner, and 500,000 servicemen received training at the base. The grand old hotels would never regain the prestige they had briefly enjoyed. Transportation innovations—namely the rise of the automobile and the construction of the first auto bridge to the city in 1926—contributed to the changing vacation preferences of Americans. According to Funnell, the railroad had encouraged people to recreate in "clusters"; now individuals had the freedom to travel where and when they chose. Atlantic City's biggest population loss occurred between 1960 and 1970, when almost one-third of the city's white population left. The casino gambling trade has brought a resurgence in the boardwalk's popularity, but the longer-term implications of this industry on the Atlantic City community are ambiguous at best.

Continued >>>

Last Modified: Mon, Jan 10 2005 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nj1/chap4.htm

![]()

Top

Top