.gif)

|

National Park Service

|

|

RUSSIAN-AMERICAN COMPANY MAGAZIN

excerpts from National Register of Historic Places

Inventory—Nomination Form

1. Name

Russian-American Company Magazin (storehouse)

Erskine House and Baranof Museum

2. Location

101 Marine Way

Kodiak, Alaska

3. Classification

Category: Building; Ownership: Public; Status: Occupied; Accessible: Yes, restricted; Present Use: Museum

4. Owner of Property

City of Kodiak

P.O. Box 1397

Kodiak, Alaska

5. Location of Legal Description

Kodiak Island Borough Assessing Department

710 Mill Bay Road

Kodiak, Alaska

6. Representation in Existing Surveys

National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings

National Park Service

Washington, D.C.

1960-62

|

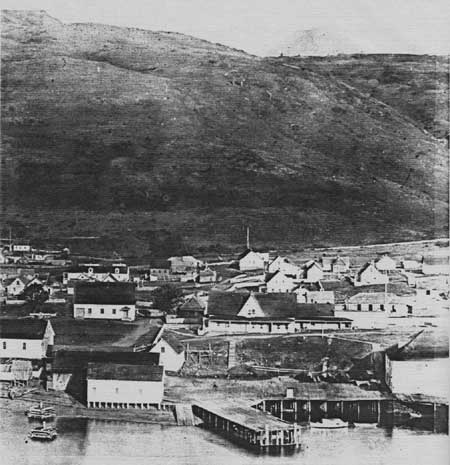

| Russian America Co. Magazin, by Gary Candeleria, 1984. |

7. Description

Condition: Good, Altered, Original Site

Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance

The Setting

The only Russian-era building remaining in Kodiak, Alaska, is the structure known as The Erskine House. The name derives from one of its several owners, Wilbur J. Erskine, who purchased the house in 1911 and lived in it until 1948, when he sold it. The more correct name for the building is related to its historic use, the Russian-American Company magazin (storehouse), or simply, the magazin.

The magazin is in the heart of "old" Kodiak. The building is on Center (formerly Main) Street near Marine Way, on the southwest corner of Block 16, facing southeast. It sits on a bluff which rises 30-40 feet above the channel separating Kodiak Island from Near Island. Southeast of the building is the remnant of a seawall built by the Russian-American Company to serve as a dock and a foundation for a large warehouse which was completed around 1860. A modern warehouse now rests on this seawall, but the original Russian rock work and anchor rings are visible from the water.

The Russian-American Company magazin is today the only building on Block 16 and is surrounded on all sides by a park, which, with the structure, is owned by the City of Kodiak. This park is well maintained. Adjoining Block 16 to the northeast are four oil storage tanks belonging to Standard Oil Company. Southeast of the magazin across Marine Way, is a Standard Oil warehouse, noted above as being on the old seawall. West of the seawall is a modern dock at which a large ship has been drydocked and which is now used as a cannery. At the foot of Center Street, at the junction with Marine Way, is a new city building which houses the ferry terminal, Chamber of Commerce, and the Visitor's Information Center. Across Center Street from the magazin is an office building. (Photos 1-4)

Although modern Kodiak appears to press in on the old magazin the property always has been in the center of a bustling maritime community. A map, dating from 1808, shows a warehouse (magazin) on the site of the present-day structure, surrounded by a church, the "Governor's House," workshops, and dwellings. (Photos 5 and 5a). A 1965 report prepared for the National Park Service described the magazin, then a private residence, as being surrounded by a medical clinic and offices of the Alaska Fish and Game Department.1 The Russian-American Company structure today is actually more isolated on its site than at any time in the past, encircled as it is by the park.

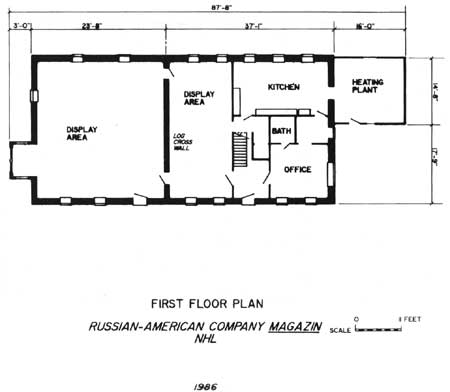

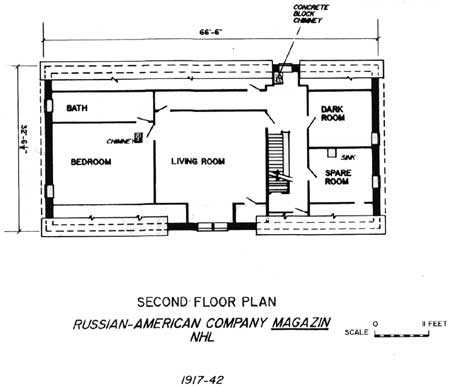

Today the City of Kodiak leases the Russian-American Company magazin to the Kodiak Historical Society. The first floor is occupied by a museum, while the second floor contains the offices of the Society.

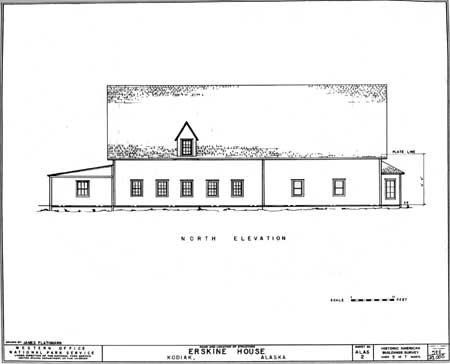

The Historical Structure

The Russian-American Company magazin is a rectangular log structure covered with horizontal wood lap siding. It has two full stories and an unfinished attic. The building measures 36 feet by 72 feet, exclusive of a one-story porch which extends across the southeast facade and is partially enclosed with glass. There is an enclosed one-story shed housing a heating plant attached to the northeast end of the building. On the southwest wall of the first floor there is a bay window. The structure has 2,152 square feet on the ground floor and 2,112 square feet on the second floor. (Photos 6-9) The gable roof is shingled and is steeply pitched, rising from the ceiling of the first floor, with an additional center front facade gable. There is a single dormer in the rear, near the northeast end.

Something of the roofing system can be interpreted from unfinished spaces running along the eaves on the second floor. Access to these is gained through a low opening at floor level in the front room of the second floor. Here the original construction has been left exposed. (Photo 10) Joists run longitudinally (E-W); they average approximately 15" in diameter and are not squared; they are laid approximately 10' on center. The joists are notched into a round sill log, which in turn supports 3' uprights, 6" x 3". A horizontal plate rests on the uprights, providing support for the rafters, 4" x 4", spaced about 5' apart. (Illustration A) In the attic the roof is exposed. The original rafters have been augmented with 2" x 8" supports spaced 2' apart. These double the original rafters. The date of this work is not known, except that it was before a fire in the 1930's, as both old and "new" rafters are charred. 2" x 8" rafters also were used to construct the front gable. A report by architect Alfred C. Kuehl for the National Park Service in 1963 noted that "Roof rafters and sheathing are not original."2

The walls of the magazin are composed of horizontal fir logs, forming a box-like structure. The logs are rough-hewn and planed flat on both the exterior and interior. The bottoms are concave and the tops convex to form a saddle fit. The logs are caulked with moss. (Photos 11-13) There are no corners exposed to view joining techniques. The interlocking of the logs is visible in the interior where wall coverings have been removed to reveal the original construction. (Photo 14 and Illustration B) The exterior walls are 8" to 11" thick, determined from the depth of the window casings. (Photos 11 and 15) They are covered by two layers of siding. The inner layer is of rough boards applied vertically and is of unknown derivation and time of placement. photograph taken in the 1940s shows streaks of what looks like paint or whitewash. The exterior layer of lap siding is redwood. (Photo 11).

Archaeological evidence indicates the first floor of the Russian-American Company building was originally divided into two large rooms with possibly two or three smaller rooms on the northeast end.3 The two rooms were separated by a log partition which did not have a communicating doorway. This wall is still in place and is of hand-hewn logs varying in diameter from 9" to 16". The tops are concave and the bottoms convex so as to fit snugly. (Photo 13) The sides are squared off to make a reasonably flush wall. These logs interlock, as described above. According to the long time owner of the building, W. J. Erskine, the log wall originally "divided the lower floor in two, leaving the store on the left, looking toward the building, and a large room on the right side, which provided for some storage and a sort of public room, where gatherings and parties were held. To the right of the large public room was the kitchen, and a little dining room."4

The earliest photographs show the structure well supplied with windows. There were six (possibly seven) on the first floor front facade, all being two light, double-hung one-over-one. Also in the front gable there were two windows, both six-over-six lights. The northeast facade is visible in an early photograph and shows one window in the attic, two on the second floor (within the end gable) and one on the first floor. (Photos 16 and 17) A second window on the first floor northeast facade is not visible in these pictures. A 1906 photograph shows a portion of the rear of the first floor and five windows (photo 18); two are out of sight.

There were two entries to the building, the main one apparently through a door under the right eave of the front gable. There was another door to the left of this door, but its location has shifted. In the earliest photograph (ca. 1880), the opening was to the left of the southwest eave of the front gable (photo 16). By 1898, it was in its present location, just to the right of this eave, at the location of a window, while a window replaced the former door. (Photo 19)

Inside the righthand door is a stairway to the second floor and a door to the right which leads to two or three smaller rooms, including a kitchen. (Photo 20) The stairwell is sheathed in horizontal tongue-and-groove boards, as is the small room to the east of the stairs. The stairwell, sheathing, and balustrade appear to be original to the structure. (Photo 21). The rear dormer is opposite the top of this stairway at the end of a short hall.

There are no extant records which describe the original flooring of the building. Presently, the flooring is 3" tongue-and-groove, which is not original. In 1963, National Park Service Landscape Architect Alfred C. Kuehl conducted a field inspection of the structure and reported, "Observation of the crawl space under the house i.e. magazin revealed hewn floor joists and beams."5 The ceiling on the first floor is 5" tongue-and-groove decking and once supported a layer of dirt and moss which served as insulation. The floor and ceiling in the second story are not original. The dirt insulation has been removed from both floor systems.

The heating system also is not documented before the 1890s. Photographs from those years show two brick chimneys rising above the main sections of the building. (Photo 16)

Little can be deduced about the partitioning of the second floor. All of the walls are sheathed in horizontal tongue-and-groove boards, which is a typical Russian finishing. (Photos 22 and 23) Combined with the finishing of the stairwell, this suggests that the upstairs may have been used as living quarters from an early date, and quite likely during the Russian era.

Modifications to the Structure

The old Russian magazin has experienced some modification, but it is essentially the same Russian structure noted in a map of the 1860s and very likely dates from as early as 1808. The size and shape of the building are unchanged; its basic log construction also remains unchanged. The present arrangement of rooms on the first floor is the same as in the earliest accounts. The stair well, balustrade, and interior wall finishings of the stairwell and second floor are probably original. The major modifications of the structure are: possible changes in the roof line, from hipped to gable; the addition of a front gable early in the historic period; and the addition of a bay on the southwest facade. Other modifications include the replacement of the original log foundation, first with graywacke or slate beach slabs and then concrete (although the original floor joists are intact); relocation of one of two front doors; the addition of two layers of siding on the exterior; the partitioning of the second floor; the addition of a stairway to the attic; removal of the stove from the first floor and the brick chimneys altogether; and the glassing in of the front porch. The first-floor ceiling is original, but the dirt insulation has been removed; both the ceiling and flooring of the second floor are not original. There has been modernization of utilities as well, including the addition of electricity, modern plumbing, and forced-air heating provided by a furnace housed in a shed on the northeast side of the building. A Halon fire suppression system has been installed.

From the evidence, it seems clear that the Russian-American Company built the structure originally as a storehouse, possibly with some living quarters. In the early 1860s a larger warehouse was built on the seawall, southeast of the magazin, probably supplanting the building's storage functions. It seems feasible that at this time, in the 1860s, the front gable may have been added or modified to provide more light for the second floor. In size and style, the building is not unlike the two-story fur barn built at Fort Ross, that is, two stories with finished, although rough-hewn, exterior walls and windows on both floors. Only the roof style is different. One report based on the U. S. Army's 1869 map asserts that the structure had a hipped roof (as the barn at Fort Ross did), which was replaced by the present gabled roof in a later year (but before the first photograph).6 Such a hipped roof does not appear on copies of the 1869 map now available. The front gable appears not to be original to the structure and post-dates the present roof, as its framing is of later construction and a portion of the old shingled roof shows within the gable in the attic. Nonetheless, while this gable may not have been original, front gables on both hipped and horizontal pitched roofs were a common design feature in the buildings of old Sitka, prior to 1867.7

At some time the log magazin was sheathed with vertical siding. From the only evidence, a photograph from the Erskine years (photo 11), it is not possible to tell whether this was finish siding or underlayment for the redwood lap siding now in place on the exterior. What looks like paint on the vertical inner boards suggests that it was probably exterior siding, later covered by the redwood horizontal lap. Vertical siding was used by the Russians at Fort Ross on the chapel, built around 1824. It seems possible, then, that the vertical siding was added by the Russians. Further analysis of this siding would be warranted, for if it should be redwood, it would suggest that it was put in place during the Russian's occupation of Fort Ross, where they had access to redwood, that is, between 1812-1841. As for the exterior horizontal siding, Mr. Erskine has stated that the Alaska Commercial Company brought redwood sheathing from California in 1883 to refurbish all of their properties in Kodiak.8 The building is visible in a photograph from ca. 1870-1890, and stands out as the only structure with paint. This may indicate either its importance in the community, or its antiquity and need for preservation. (Photo 17)

The Alaska Commercial Company, which owned the building from 1867 to 1911, made several changes in the structure. The left front door, into the southwest room, was relocated sometime before 1898, the old doorway being made into a window. The right-hand door, into the "public" end of the building, has remained unchanged. The Alaska Commercial Company also outfitted the first floor as a residence. Two doorways were cut through the log partition wall. Photographs from 1906 show vertical bead-board wainscoting in the first-floor living areas. (Photo 20) Bead-board also was used on the ceiling of the second story and arranged horizontally on the stairwell leading to the attic. This finishing material is of post-Russian vintage.

Another major change made by the Alaska Commercial Company was the addition of a bay. A photograph from ca. 1898-1900 (photo 19) shows the bay in place, and an interior photograph from 1906 show its furnishings (photo 24). On the other end of the building, the Company added a long one-story extension, but this has not survived. (Photo 19)

From 1911 to 1948, W. J. Erskine owned the structure and put his own stamp on it. In 1940, he replaced the log foundation with graywacke or slate beach slabs.9 In 1942 the Erskines enclosed part of the porch with glass, as it is at present.10 (Photo 25) They also used the entire house as a residence for the family, including the second floor.

In 1948, Erskine sold the building to Donnelly and Acheson Mercantile Company, which used it as a residential rental until 1964. In the latter year, the old magazin was acquired by the Alaska Housing Authority acting for the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Earthquake Renewal Project R-19, following the earthquake and tsunamis of March 27. Because of these twin disasters, most of the buildings around the structure were razed. In 1967 the Kodiak Historical Society leased the building for use as a museum. The Society, with funding from the Alaska Centennial Commission, exposed the interior logs and installed electricity on the first floor. Between 1967 and 1972, the Society installed a new shingle roof, enclosed the old brick chimneys on the second floor, installed two forced-air furnaces (in a shed on the northeast end of the building) and installed and insulated the duct work around the building. In 1971, the Society also introduced new ceilings, lights, and flooring into the small rooms on the northeast end of the first floor and modernized the bathroom. This section then became a caretaker's apartment. In 1972, the City of Kodiak purchased the property, and the Kodiak Historical Society continued to occupy the building under a lease. A chronology of improvements since 1974 follows:

| 1974 | Rock retaining wall built along Center Street |

| 1975 | Burglar alarm system installed |

| 1976 | Halon fire suppression system installed |

| 1978 | Concrete foundation replaced beach-slab City of Kodiak purchased Lots 1, 3, 4, of Block 16, which surround the magazin |

| 1979 | Improvements to second including wiring, painting, plumbing for a bathroom, and installation of carpet |

| 1980 | Track lighting installed in first-floor museum Removal of rot from windows on north side Park landscaping of lots 1, 3, and 4 New flooring for exterior porch |

| 1981 | Hot-water furnace installed |

| 1982 | Rock wall extended along Center Street |

| 1983 | Center Street stairwell repaired Interior and exterior porch repaired and painted |

| 1985 | Strengthening of second floor Brick chimneys removed on second and third floors Electric plugs installed in first-floor exhibit area |

Conclusions

Evidence from archaeology, materials' analysis, and early nineteenth-century maps and drawings indicates that the Russian-American Company built a storehouse on the Kodiak site between 1804 and 1808. A lithograph of Kodiak by Iurii I. Lisianskii in 1804 shows no building of similar size or construction near the waterfront,11 while a map made in 1808 shows a large structure, designated on its accompanying key as the "newly built magazin" (storehouse) on the site of the present structure. (Photos 5 and 5a) A map of Fort Kodiak, made in 1869 for the United States Army, also shows a large rectangular building on the site. (Map 1) Hand-wrought nails taken from the exterior walls are similar to those recovered at Fort Ross;12 construction at the latter site occurred between 1812 and 1840. (Hand-wrought nails had been generally replaced by machine-cut after 1820.)13

The earliest photographs of the building come from the 1870s or 1880s, during the era when the warehouse was owned by the Alaska Commercial Company. These show a structure in appearance very much like the present, that is, a two-story building with a steeply pitched roof with three gables, and a front verandah. (Photos 16, 17, and 26) It is safe to assume this was the same structure denoted in both the 1808 and the 1869 maps, at least in its basic configuration.

The magazin was originally built as a warehouse for furs and as such is more crudely constructed than other structures from the Russian era in Alaska, such as the Russian Bishop's House or Building 29, both at Sitka. The logs are not carefully matched, the hewing is rough, and squaring is casual to provide a reasonably flush surface. Longitudinal joinings, where logs are joined to achieve the necessary length for a wall, are very crude, but stable and secure. Moss and earth insulation and evidences of previous canvas wall covering (witness the nails mentioned above), are typical of Russian construction, as is the lack of an interior passage between the two main rooms on the first floor.

The roughness of construction is appropriate for the early date and function of the building. Refinements such as the numbering system marked in the logs by the hewers who worked on Building 29, Sitka, did not occur until Russian-American Company Governor Etolin imported Finnish carpenters into Alaska in the early 1840s.

With the exception of the enclosed porch, the bay in the southwest facade, and the heating-plant enclosure on the northeast wall, the exterior configuration of the building is as it was in the earliest photographic evidence, ca. 1880. The interior has been modified extensively, but the first floor has been returned to what appears to be its Russian-period plan. The basic frame of the building retains much integrity, including the main interior walls on the first floor. The historic fenestration pattern and many of the original windows are still intact. The stairwell and balustrade from the first to the second floor remain unchanged from the historic period. Unfortunate losses are the original chimneys and all of the original wall coverings and insulation.

FOOTNOTES

1John A. Hussey, Robert S. Luntey, and Ronald N. Mortimer, "Feasibility Report, ERSKINE HOUSE, Kodiak, Alaska (San Francisco: U. S. Department of Interior, National Park Service, Western Regional Office, 1965).

2Ibid., p. 10.

3Anne D. Shinkwin and Elizabeth F. Andrews, "Archeological Excavations at the Erskine House, Kodiak, Alaska—1978," (unpublished manuscript, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska, May, 1979), p. 2.

4Letter, Wilbur J. Erskine to E. L,. Keithahn, October 8, 1948, Erskine Collection, Kodiak Historical Society. A Copy is in the NPS (ARO), Anchorage.

5Hussey, et al, "Feasibility Report," p. 10.

6Ibid., p. 24.

7Lady Franklin Visits Sitka, Alaska, 1870: The Journal of Sophia Cracroft, Sir John Franklin's Niece, ed. by R. N. DeArmond (Anchorage: Alaska Historical Society, 1981), figures 7 and 10, p. 15.

8Erskine to Keithahn, October 8, 1948.

9Ibid.

10Letter, Nellie Erskine to Bill Roberts, August 1, 1942, Erskine Collection, Kodiak Historical Society. Copy is in NPS (ARO), Anchorage.

11Hussey, et al, "Feasibility Report," p. 25.

12Letter John C. McKenzie to Marian Johnson [1983], Kodiak Historical Society, Kodiak, Alaska. Copy is in NPS (ARO), Anchorage.

13Letter, Lee H. Nelson, Restoration Architect to William S. Hanable, Historian, State of Alaska, November 23, 1971, Kodiak Historical Society, Kodiak, Alaska. Copy is in NPS (ARO), Anchorage.

|

| Kodiak with former Russian America Co. Magazin at center, courtesy Kodiak Historical Society. |

8. Significance

Period: 1800-1899, 1900-; Areas of Significance: Exploration/Settlement, Theme XXI, Alaska History, 1741-19??

Specific Dates: 1808-1911; Builder/Architect: Russian-American Company

Statement of Significance

A warehouse, or magazin, in Kodiak, Alaska, dating from 1805-1808, is the oldest of only four Russian structures standing in the United States. Although this alone distinguishes the building, its association with Kodiak, the first administrative center of the Russian empire in North America, the Russian-American Company, and the Alaska Commercial Company provides an additional dimension to the building's historic importance. From 1793 until 1808, the community of Pavlovsk, today's Kodiak, was the headquarters of the Russian-American Company and the main receiving point for furs from as far away as the Pribilof Islands in the north and Yakutat in the east. During this period, the Russians built a storehouse or magazin at Kodiak to house their wealth of furs before transit to Russia and the Orient. This log structure still stands on the original site. The old magazin is also noteworthy as the only edifice in North America which links the Russian and American trading companies which, for more than 100 years, shaped the scope and direction of settlement and exploration in Alaska, and controlled not only commerce, but government, law, and social relations on this most western frontier. Owned by both the Russian-American Company and the San Francisco-based Alaska Commercial Company, the two story log building played a part in the development of an intercontinental trading empire. At various times its sphere of influence embraced Russia, China, Japan, and the trading marts of London, as well as of San Francisco and New York. On June 13, 1962, the Secretary of the Interior found the magazin, locally known as the Erskine House, to nave exceptional significance in expressing the history of the United States and declared it eligible for registered National Historic Landmark status.

Historical Context

Kodiak Island, midway between the Aleutian Islands and the Alexander Archipelago, was the site of the first permanent settlement established by the Russian promyshlenniki (fur-traders) in North America. In August 1784, years after Bering's discovery of Alaska, Grigorii Shelikhov, head of a Russian trading company, established a base at Three Saints Bay (now Old Harbor) on the southeastern shore of Kodiak Island. This community on Sitkalidak Strait was named for one of Shelikhov's ships. During the next decade Three Saints became his company's principal base in America.

In 1793, however, Three Saints Bay was replaced as headquarters by another community, some 56 miles northwest on Chiniak Bay. The settlement at Three Saints had been badly damaged by earthquakes, and at high tide the whole settlement was threatened by floods. Alexander Baranov, chief manager of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, arrived on Kodiak Island in July 1791 and quickly acted to build a new site for the company's headquarters. By 1793, Pavlovsk, today the modern city of Kodiak, was ready to receive the transfer of the headquarters from Three Saints.1 For the next decade and a half, Kodiak (or Kad'iak in Russian) was the nerve center for the Shelikhov-Golikov operations. In 1799, this company was given exclusive rights to the American trade by Russian Emperor Paul I and was reconstituted as the Russian-American Company.

During the next 68 years, the Russian-American Company served as the instrument of government in Alaska, acting under charter of the imperial crown. It provided schools, supported the clergy, maintained an elaborate welfare system for disabled and the elderly, administered Russian law, collected taxes, and supervised the exploitation of the resources of the land and waters of Alaska. It also supported exploration and scientific investigation which provide much of our knowledge of pre-contact life among the coastal peoples from Sitka to Kotzebue Sound, as well as those living in the interior of Alaska along the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers.2

Kodiak, as headquarters of the Shelikhov-Golikov and later the Russian-American companies, exercised all the functions of a major Russian town. It was at Kodiak that the first Russian Orthodox missionaries established the colony's first permanent religious mission, using the settlement as a base for evangelizing among the Aleutian islands and along the Alaska peninsula. At Kodiak one of the missionaries, the monk Herman (now canonized by the Orthodox as Saint Herman) established the first school for native children Kodiak also and one of the two hospitals in Russian America. From Kodiak, huge flotillas of baidarkas went out on hunting expeditions as far east as Yakutat, returning to Kodiak with thousands of pelts, which were placed in storage ready for shipment to Russia and the markets of the Orient. Plans for development of other regional centers were made at Kodiak, and during 1799-1808, the Russian-American Company established counters, or outposts, at Atka, Unalaska, Novorossii (New Russia) near Yakutat, at Lake Iliamna and Nikolaevskii Redoubt (modern Kenai), both of the latter being taken over from their failed rivals, the Lebedev-Lastochkin Company. One of the most important administrative acts, decisive for the fate of Kodiak, was to establish a major post at Sitka. Baranov's first efforts to occupy Sitka Island (as it was then known) were repulsed in 1802 by Tlingit warriors, but by 1804, the Russian flag flew over a new fort at Novo Arkhangel'sk (Sitka). In 1808, wishing to use this new post as a base for hunting otter and seals along Alaska's southern coast and also to launch colonization in northern California, Baranov transferred the headquarters of the Russian-American Company from Kodiak to Novo Arkhangel'sk.

At the time of the transfer of the Russian-American Company headquarters to Sitka, Kodiak was a sizable community with some 50 log dwellings, many of which were of two or three stories.3 A map of Kodiak made by I. F. Vasil'ev in 1808 shows more than 25 structures, including one designated "newly built store," which is one of the larger buildings. (Photos 5 and 5a) A sketch of the community made by Captain Iurii I. Lisianskii of the sloop "Neva" during its stay at Pavlovsk (Kodiak) Harbor in 1804 shows no such building. Thus, it would seem that the new storehouse was built between 1804 and 1808, probably soon after Lisianskii's visit, but before the decision to move the headquarters to Sitka.

Although Kodiak was no longer the capital of Russian America after 1808, it was nonetheless a key post of the Russian-American Company. In 1839, Baron Ferdinand P. von Wrangell, who had recently retired as General Manager of the Company, described the Kodiak District as beginning,

at the Evdokeev Islands and includes the islands of Ukmok (Chirikov) and Kadiak, together with all the islands in the vicinity, the coast and islands of the Kenai Bay (Cook Inlet) as well as Chugach Bay (Prince William Sound). Eastward it extends as far as Cape St. Elias, westward, along the Aliaska coast as far as the boundary of the Unalashka District, the shores of Bristol Bay and vicinities of the rivers Nushagak and Kuskokvim.4

According to another source,

Kodiak was the most populous counter and the second most important counter economically...Kodiak Island itself was... diversified, with stock-raising, gardening, brick-making, and fishing as well as trapping. The island was Russian America's chief source of 'colonial products,' including yukola (dried fish), sarana (dried yellow lily bulb), cow-berries, burduk (sour rye flour soup), and blubber. St. Paul's Harbor [Kodiak] was still the largest settlement; in 1825 its population comprised 26 Russians, 41 Creoles, and 36 Aleuts.5

By 1860, Kodiak had a population of about 358 Aleuts, Creoles and full-blooded Russians.6

Aside from its importance as an administrative and supply center, Kodiak also continued to play a crucial role for the Russian-American Company in the marketing of "soft gold." Between 1842 and 1860, it shipped 5,809 sea otter, 85,000 beaver, 9,558 river otter, and 28,000 fox pelts. Sizable quantities of bear, lynx, sable, muskrat, mink, and wolverine skins also were distributed from the Kodiak counter. Only Unalaska could match Kodiak in number of otter and fox pelts, but it had nowhere so varied a selection of animals.7 Storage for this wealth was, of course, crucial to the success of the Kodiak counter. The large storehouse built in 1805-08 was kept full, yet was not large enough for this volume of merchandise, and another warehouse was built on a new dock just down the hill from it.

In addition to the traditional items of trade identified with Russian America, namely furs, Kodiak was a principal supplier of another commodity, which brought much-needed income to the Company toward the end of its reign in America. From 1855 to 1860, Kodiak shipped some 7,400 tons of ice to San Francisco. The income from ice shipped out of both Sitka and Kodiak was worth $121,956 between 1852 and 1860.8

So important was Kodiak throughout the years after 1808 that by 1818 the Company owners in St. Petersburg expressed a desire to move the capital back to Kodiak from Sitka.9 Thus,

In 1825 the shareholders of the Russian-American Company approved of the plan to return the residence of the Chief Manager and the administrative staff of the colonies to Pavlovsk Harbor (Kodiak), and three years later P. E. Chistiakov reported to the Main Office that the work was going successfully, although he was unable to assign more than 25 men to the construction work at Kad'iak.10

The move did not take place, however, because of a change in the relations between the Russian-American Company and the Hudson Bay Company, the latter's sphere impinging on the area east and south of Sitka.

By 1867, when authority in Alaska was transferred from the Russian to the American government, Kodiak had a population of about 400. A military map drawn about 1869 shows 91 buildings, large and small. Several of the structures, such as the church, the new wharf warehouse, and two storehouses—one of them today's Erskine House—were substantial, multi-story buildings. (Map 1) All of these were of Russian construction.

If one must focus on the Russian-American Company in order to understand the early history of America's most northwestern frontier, then it is no less vital to turn one's attention to the Alaska Commercial Company to examine the next phase of this history. The A.C.C., as it was widely known, was in every way as important as the Russian-American Company in affecting law, social order, education, religion, and commerce in the north. Until 188 Alaska had no civil government at all and did not possess even a district court until after 1900. Only in 1912 was Alaska given the benefits of territorial status within the United States. Until that date, remote communities were almost entirely without the protection of law, education was overseen by church missions, and the trading companies had almost unlimited power to affect the daily lives of nearly the whole populations especially those persons living beyond a day's reach of the capitals of Sitka, and after 1900, Juneau. Thus the A.C.C. must be seen as a major institution of the American west, and a significant influence on American economic and social history.

The valuable assets of the Russian-American Company were acquired by an eastern U. S. businessman, Hayward M. Hutchinson on October 11, 1867, just one week before the ceremony which ceded Alaska to the United States. Hutchinson soon transferred the Russian-American Company assets to a San Francisco firm, Hutchinson, Kohl & Company. In September 1868, the partners in this enterprise joined with other individuals to create a new firm, the Alaska Commercial Company, which was incorporated on October 10, 1868.11 Included in the properties which were transferred to the Alaska Commercial Company were most of the Russian-American Company buildings at Kodiak, as well as at other communities in Alaska.

Perhaps excluding private dwellings, the only buildings in the town not transferred were those belonging to the Orthodox Church, and certain public buildings, such as the 'governor's house,' school, batteries, hospital, an office, surgeon's house, and one or two others which were to be delivered to the United States Government.12

Two years after its founding, the Alaska Commercial Company entered an arrangement with the U. S. Government which was of immense financial advantage to both parties. The Government gave the A.C.C. exclusive rights to harvest the fur-bearing seals off the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea.13 The Company could take up to 100,000 seals per year and was to pay the government a tax of $2.62 on each pelt. In exchange for this generous lease, the Company was to maintain schools on the Pribilof Islands of St. George and St. Paul, and to provide for their native Aleuts, both in wages and in health care. The benefit to the U. S. Government was substantial. Within 40 years from the Purchase of Alaska, the U. S. Treasury received from the Alaska Commercial Company more than $9,473,996, or $2,200,000 more than the purchase price of Alaska. According to an informal history of the Company.

All of the company's seal skins from Alaska Seal Islands [the Pribilofs] were shipped to San Francisco, the skins discharged on the dock from the steamers, and counted out under supervision of Treasury officials. They were packed on the dock, with a liberal allowance of salt, in especially built barrels or casks, and then shipped by railroad to New York, then to London.

All other furs were brought to the company's building in San Francisco, put in shipping condition, and then also forwarded to London.14

Clearly, the activities of the Alaska Commercial Company affected not only Alaska, but the United States and the world economy.

The discovery of gold on the Klondike River in 1896 introduced a whole new range of activity to the Alaska Commercial Company. The Company had 16 barges which it put into service shipping freight north from San Francisco and up the Yukon to Dawson, Yukon Territory. Its fleet of 14 river and five ocean steamers provided transportation for the hordes of miners trying to reach Eldorado. New communities were started to service this flood of humanity, and every village on the A.C.C. routes was profoundly affected, no only financially, but socially as well. Transportation was only one of the Company's many responses to the new economic opportunities of the Gold Rush. A.C.C. also served as the first bank in Dawson, as it had the only safe deposit vault in that boom town. The Company built the first sawmill in the Klondike country, providing lumber for the sluice boxes and homes for the miners. Outfitting the miners and provisioning the new gold-struck communities enlarged the Company's activities to nearly every hamlet in Alaska. Ultimately, the Company maintained 86 stores in Alaska and the Yukon Territory and five in Siberia.

Typically, a community had only one store, and the overwhelming majority of these were owned by the Alaska Commercial Company. The store not only sold necessities and luxuries, but purchased goods—usually furs—from the local population—usually Natives. This led, in many communities, to abuses and complaints against the Company. The extent of the reach of the A.C.C. into the communities is evident from the censures levelled at its methods. Among the most articulate and persistent critics of the Company were the Russian Orthodox clergy, whose Native congregations were most egregiously affected. The pages of the church's official publication ring with denunciations of the high-handedness of the Company agents. In 1896, the journal noted:

The moment you leave Sitka and steer northward, you enter the realm of the North American Commercial and the Alaskan Commercial Companies; Kadiak, Nutchek, Kenai, Unalashka, with a host of native settlements, are completely in their hands. If you want to buy or sell anything, you go to the Company's store. Outside of the store you won't get a piece of hard tack half eaten by mice, though you were starving to death. The Company's agents lord it over all the settlements. They are literally the masters in every one of them. They control everything and are controlled by nothing. Should a native, even though a white man, take it into his head to refuse him obedience, an agent will think nothing of starving him, forbidding him the store, and driving him out of the settlement into the woods...With whom could a complaint be lodged?15

In a letter to President McKinley in 1899, Bishop Nicholas of the Alaska diocese of the Orthodox church pleaded,

A limit must be set to the abuses of the various companies, more especially those of the Alaska Commercial Co., which for over thirty years, has had there the uncontrolled management of affairs and has reduced the country's hunting and fishing resources to absolute exhaustion, and the population to beggary and starvation.16

Despite complaints against the Company, the Orthodox, as well as other churches and the U. S. Government found themselves also grateful to the management of the A.C.C. for its assistance in building both schools and churches.

The Alaska Commercial Company was not alone in attempting to make maximum profit from the Gold Rush. The fierce competition between several companies brought many of them to the brink of financial disaster, the Alaska Commercial Company included. In 1901, the Company merged with several of its rivals to form two subsidiary corporations—the Northern Commercial Company, which assumed most of the mercantile and trading activities of the founding firms; and the Northern Navigation Company, which took over the transportation function.

As a result of this arrangement, the Alaska Commercial Company in 1902 sold to the Northern Commercial Company most of its mercantile properties and interests except its sawmills and mining claims. It retained its holdings at Dutch Harbor, Unalaska, and at Kodiak, as well as at several other posts. Most of the retained assets were disposed of during the next decade or two, so that the Alaska Commercial Company developed more and more into a holding company.17

The account books of the A.C.C. show that it continued to operate an active trading station at Kodiak until 1911.

On January 1 of that year the buildings and property inventory for the Kodiak Station included a dwelling, warehouse and wharf, store, the Custom House lot, old 'Russian Company' land claims, about 30 acres of 'pasture meadow,' cooper, carpenter, and blacksmith shops, stable, 'native house,' powder house, and various other structures, furniture, and fixtures, not all of which were in the town of Kodiak itself.18

During the years of Alaska Commercial Company ownership, the old Russian storehouse was given new uses. It was outfitted to serve as a residence, and possibly also to house Company officials and guests, for it remained one of the largest, and most imposing buildings in the town. Photographs from the late 19th century clearly show the building with its distinctive front gable, outstanding among the surrounding structures, its basic box-like configuration unchanged in almost 100 years. (Photo 26)

About the middle of 1911, the Company sold its Kodiak District properties to "an old and trusted employe, Wilbur J. Erskine."19 The Company discontinued paying its Kodiak agent in that year, and Erskine, operating under the firm name of Erskine and Fletcher, went into debt to A.C.C. both for the fixed assets and the merchandise. Although the Company foreclosed on Erskine in 1932, it seems that he must have made good his debt, for in 1948, he referred to one of the buildings as "my residence,"20 and his heirs subsequently sold both the residence and other properties to the mercantile firm of Donnelly and Acheson. The Erskine residence was in the old Russian-American Company magazin.

Built by the Russians by 1808, the solid log, two-story structure had served Wilbur Erskine, the Alaska Commercial Company, and the Russian-American Company, as residence, store, and warehouse. Although of relatively crude construction, the Russian magazin was nonetheless the safeguard for the tremendous wealth of the Russian-American Company. It was built to last. And it has survived as one of only four Russian structures remaining in the United States. It is also essentially the same box-like structure erected by the Baranof administration, its walls and basic floor plan still intact. Among the surviving Russian era buildings, the Kodiak magazin has an additional distinction. It is the only structure which embraces the activities of both the Russian-American and Alaska Commercial companies, enterprises which shaped the face of northwestern America. Engaged not only in commerce, but in administration, law enforcement, and exploration, these companies were truly the masters of Alaska from whence they ruled the fur markets of the world.

FOOTNOTES

1Svetlana Federova, The Russian Population in Alaska and California, Late 18th Century—1867, trans. and ed. by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly, Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 4 (Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1975), pp. 114-115, 121.

2P. A. Tikhmenev, A History of the Russian-American Company, ed. and trans. by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978).

3Archibald Campbell, A Voyage Round the World from 1806 to 1812., (Edinburgh, 1816) pp. 107-108, cited in John A. Hussey, Robert S. Luntey, and Ronald N. Mortimore, "Feasibility Report, ERSKINE HOUSE, Kodiak Alaska" (San Francisco: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Western Regional Office, 1965), p. 16.

4Ferdinand Petrovich Wrangell, Russian America: Statistical and Ethnograhic Information, trans. by Mary Sadouski and ed. by Richard A. Pierce, Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 15 (Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1980), p. 3.

5James R. Gibson, Imperial Russia in Frontier America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), p. 18.

6Hussey, et al, "Feasibility Report...", p. 18.

7Captain Pavel N. Golovin, The End of Russian America: Captain P. N. Golovin's Last Report, 1862, trans. and ed. by Basil Dmytryshyn and E. A. P. Crownhart-Vaughan, North Pacific Studies Series, No. 4 (Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1979), appendix 7, pp. 162-165.

8Ibid., appendix 10, p. 207.

9V. M. Golovnin, Around the World on the "Kamchatka," 1817-1819, trans. with introduction by Ella Lury Wiswell (Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1979), Appendix 5, p. 306fn.

10Federova, The Russian Population of Alaska, p. 219.

11Hussey, et al., "Feasibility Report," p. 19.

12Ibid.

13Samuel P. Johnston, Alaska Commercial Company, 1868-1940 (n.p. n.d.), p. 9.

14Ibid., p. 36.

15"News from Alaska," Pravoslavnyi amerikanskii vesthik [Russian Orthodox American Messenger], I, 11 (February 1-13, 1897), p. 206.

16Bishop Nicholas, Diocese of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, "To His Excellency, William McKinley, President of the United States," Amerikanskii pravoslavnyi vesthik [Russian Orthodox American Messenger], III, 1 (January 1-13, 1899), p. 7.

17Hussey, et al., "Feasibility Report," p. 20.

18Ibid., p. 21.

19Johnston, The Alaska Commercial Company, p. 65.

20Letter, Wilbur J. Erskine to E. L. Keithahn, October 8, 1948, Erskine Collection, Alaska and Polar Regions Department, Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska. A copy is at the Kodiak Historical Society, Kodiak, Alaska.

9. Major Bibliographical References

Articles

Nicholas, Bishop of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. "To His Excellency, William McKinley, President of the United States."

Amerikanskii pravoslavnyi vestnik [Russian Orthodox American Messenger], III, 1 (January 1-13, 1899), 6-9.

"News from Alaska." Pravoslavnyi Amerikanskii vestnik [Russian Orthodox American Messenger], I, 11 (February 1-13, 1897), 205-207.

Books

Federova, Svetlana G. The Russian Population in Alaska and California, Late 18th Century-1867. Trans. and ed. by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly. Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 4. Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1975.

Gibson, James R. Imperial Russia in Frontier America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Golovin, Captain Pavel N. The End of Russian America: Captain P. N. Golovin's Last Report, 1862. Trans. and ed. by Basil Dmytryshyn and E. A. P. Crownhart-Vaughan. North Pacific Studies Series, No. 4. Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1979.

Johnston, Samuel P. Alaska Commercial Company, 1868-1940. N.P. N.D.

Tikhmenev, P. A. A History of the Russian-American Company. Ed. and trans. by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978.

Wrangell, Ferdinand Petrovich. Russian America: Statistical and Ethnographic Information. Trans. by Mary Sadouski, ed. by Richard A. Pierce. Materials for the Study of Alaska History, No. 15. Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1980.

Manuscript Collections

Alaska Commercial Company Collection. Graduate School of Business Library, Stanford University. Palo Alto, California.

Erskine Collection. Alaska and Polar Regions Department, Rasmuson Library. University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska.

Unpublished Reports

Hussey, John A.; Luntey, Robert S.; and Mortimore, Ronald N. "Feasibility Report, ERSKINE HOUSE, Kodiak, Alaska." San Francisco: U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Western Regional Office. 1965.

Shinkwin, Anne D. and Andrews, Elizabeth F. "Archeological Excavations at the Erskine House, Kodiak, Alaska—1978." Fairbanks: University of Alaska, May 1979. Copy at Kodiak Historical Society, Kodiak, Alaska.

10. Geographical Data

Acreage of nominated property: Less than 1 acre; Quadrangle name: Kodiak (D-2), Alaska; Quadrangle scale: 1:63,360; UTM References: 05 535600 6405100

Verbal boundary description and justification

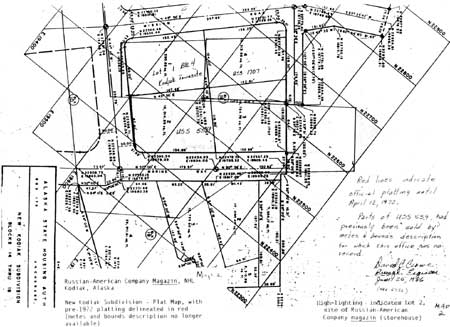

Lot 2, Bloock 16, New Kodiak Subdivision (Complete re-platting occurred after 1964 tsunami and urban renewal--see attached plat map)

11. Form Prepared By

Barbara Sweetland Smith

Alaska Regional Office

National Park Service

2525 Gambell Stree

Anchorage, Alaska

November 30, 1986

12. State Historic Preservation Officer Certification

|

| RUSSIAN-AMERICAN COMPANY MAGAZIN NHL. From Milepost, 1985 (Alaska Northwest Publishers) |

|

| Russian-American Company Magazin NHL, Kodiak, Alaska. |

|

| Russian-American Company Magazin NHL, Kodiak, Alaska. Detail from Map of Fort Kodiak, Alaska Territory, 1869 (1 of 3) |

|

| Russian-American Company Magazin NHL, Kodiak, Alaska. Detail from Map of Fort Kodiak, Alaska Territory, 1869. The magazin is outlined in red. (2 of 3) |

|

| Russian-American Company Magazin NHL, Kodiak, Alaska. Key to Map of Fort Kodiak, Alaska Territory, 1869. (3 of 3) |

|

| First Floor Plan, Russian-American Company Magzin NHL, 1917-42. |

|

| First Floor Plan, Russian-American Company Magzin NHL, 1986. |

|

| Second Floor Plan, Russian-American Company Magzin NHL, 1986. |

|

| Details, Russian-American Company Magzin. |

|

| Second Floor Plan, Russian-American Company Magzin NHL, 1917-42. |

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

Last Modified: Mon, July 28 2008 8:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/russian-america/sec5.htm

![]()

Top

Top