|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 10:

RECREATION AND TOURISM (continued)

Recreational Trends, 1940-1970

The Kenai National Moose Range is Established

On December 16, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8979, which established the Kenai National Moose Range. The range reserved much of the western side of the Kenai Peninsula in order to ensure the preservation of the local moose population.

The movement to create a game range on the western Kenai had been a long time in coming. Back in 1904, when forester William Langille made his initial venture into the area, he was quick to note that big game was an important peninsula resource; moose, caribou, sheep, and bear were all noted. Langille noted that

the game of the region should be a source of revenue to the people and of pleasure and sport to the outsiders who wish to hunt, and there should be some meeting place where the game can be conserved, clashing interests harmonized and trophy hunting permitted. [67]

Nothing came of Langille's recommendations, but they were not ignored. In 1916, forester Arthur Ringland, worried about game poaching by trophy hunters, repeated those recommendations. [68] But the U.S. Forest Service had little intrinsic interest in game protection, and the issue lay fallow for more than a decade. During this period, the number of homesteads grew in both the Kenai and Homer areas. Increasing settlement, along with increased market hunting, caused federal authorities to worry about the permanence of the peninsula's moose population. In 1931, therefore, the Alaska Game Commission recommended, at its regular annual meeting, that an 800,000-acre (1,230 square mile) moose sanctuary, to be located in the northwestern part of the peninsula, be established by presidential proclamation. [69]

That recommendation, although not acted upon, set off a long-running investigation into the size and health of the Kenai moose herd. The Game Commission, using donated funds, dispatched guide Henry Lucas into the Skilak-Tustumena lakes area in 1932. Lucas discovered, due to Game Commission enforcement efforts, that the moose population was no longer declining; he also noted that local residents were firmly in favor of a moose sanctuary being established. The Game Commission, after studying the matter during a second field season, backed the idea of a moose sanctuary in the Skilak-Tustumena lakes area; that area, however, promised to be controversial because it was a prime trophy hunting area. Before long, the federal Bureau of Biological Survey promoted a competing plan, for a 500,000-acre moose sanctuary in the northern part of the peninsula (that is, in the same general area that the AGC had recommended in 1931). By 1934, interagency differences on the proposal had still not been resolved; this impasse had the practical effect of shelving any protection proposals for the time being. [70]

In the late 1930s, new worries about a perceived decline in the peninsula's moose population sparked another round of studies. Biologist L. J. Palmer spent the 1938 field season in the Skilak-Tustumena lakes area. He confirmed a long-term moose decline, but instead of a moose sanctuary, he recommended that the area be set aside as a moose and mountain sheep reserve. The area would be open to limited hunting, but closed to homesteading or other land location without special permits. He returned to the field that winter, and came back convinced more than ever that a moose range needed to be established. [71] Palmer's research provided the technical data necessary to justify the moose range idea; two years later, Ira N. Gabrielson applied the idea politically and established the moose range. Gabrielson, a leading conservationist, was the head of the newly established U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It was he who guided the proposal–a far grander proposal than Palmer had ever envisioned–through the agency and on to Roosevelt's desk. [72]

The Kenai National Moose Range, as enacted, covered some 2,000,000 acres. As stated in the proclamation, the range was established

for the purpose of protecting the natural breeding and feeding range of the giant Kenai moose on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, which in this area presents a unique wildlife feature and an unusual opportunity for the study in its natural environment of the practical management of a big game species that has considerable economic value.... [73]

Although the range was primarily established to protect wildlife habitat, its southeastern boundary followed the top of the Kenai Mountains drainage divide and covered more than 100,000 acres of the Harding Icefield. Tens of thousands of these acres, located high in the Kenai Mountains, are now part of Kenai Fjords National Park.

By the time President Roosevelt signed the Kenai National Moose Range proclamation, Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and World War II was at hand. Understandably, therefore, the range remained undeveloped for the next several years. It was not until 1948 that the first administrative facilities, at Kenai, were established. That September, David L. Spencer was appointed as the refuge's first manager; James D. Peterson was his assistant. [74]

Recreational Activities Along the Southern Coast

As has been noted (both in Chapter 9 and in a section above), commercial fishers and sightseeing parties were first lured to Resurrection Bay in the early years of the century and consistently used the resource in the decades that followed. The historical record is less forthcoming about Resurrection Bay sport fishing in the years prior to 1940. Most likely, sport fishing was a popular activity in and around Seward, and it may have also been part of early Resurrection Bay sightseeing activities.

After 1940 these trends continued. As Chapter 8 has noted, the military buildup prior to World War II brought thousands of soldiers to Seward's Fort Raymond and to the remote posts of Fort Bulkley (Rugged Island), Fort McGilvray (Caines Head), and similar installations scattered around Resurrection Bay. To cater to the soldiers' recreational needs, a variety of activities were organized. As early as April 1942, military authorities were sponsoring sightseeing and fishing excursions on Resurrection Bay. These seven-hour trips took place twice each week and appear to have continued, on a seasonal basis, through the summer of 1944. [75]

After the war, activity in Seward dropped off. But local officials, hoping to popularize the town, were buoyed by ongoing road development projects elsewhere on the peninsula and seized on those activities as opportunities to attract outsiders.

Several activities soon came to the fore. In 1950, before Seward gained its road link to Anchorage, local boosters began to advertise the traditional Mount Marathon race to out-of-towners. Five outsiders answered the call that year, and in 1951 a non-Seward resident won the race for the first time. During the mid-1950s, several nationally popular magazines noted the race in Alaskan feature articles. Over the years, the race attracted an increasing number of out-of-town contestants and their families. In recent years the Fourth of July race, and various associated events, have attracted thousands of participants and spectators each year. [76]

The road connecting Anchorage (and the rest of the Alaska road network) with the Kenai Peninsula was completed in October 1951. Soon afterward, residents from other communities began coming to Seward to fish and boat on Resurrection Bay. The number who engaged in such activities was at first fairly small. The migration was sufficiently large, however, to augment the fortunes of local businesses that sold licenses and gear, operated and coordinated charters, and processed fish. By 1953, sport fishing was sufficiently popular to attract the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; the agency dispatched an enforcement patrolman, Joseph Widauf, to Seward for the silver salmon season. Widauf reportedly "did a very good job acquainting the sportsmen with the regulations and keeping violations at a minimum." [77]

In 1956, Sewardites took a major new step when the town hosted its first Silver Salmon Derby. The event was the brainchild of local residents Jim and Celia Wellington. Juneau, by this time, had been holding its salmon derby for more than twenty years, and the Wellingtons, former Juneau residents, borrowed the idea and brought it to Seward. The derby, sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce, was held on two successive weekends in August; the proceeds of the event were used to stock local streams with game fish and to finance other local improvements. The contest quickly caught on with both locals and out-of-town residents, and by the mid-1960s, "large numbers of sports fishermen [were harvesting] a high proportion of the silver salmon entering Resurrection Bay." [78]

Pleasure boating also grew during the 1950s. Soon after highway from Anchorage was completed, locals formed the Seward Small Boat Owners' Association to improve the facilities in the small boat harbor. Then, in March 1957, the Anchorage-Seward Yacht Club was founded to promote nautical recreation and to push for harbor improvements. The organization, renamed the Alaska Yacht Club, was incorporated in January 1958. The club, which by the 1970s was known as the William H. Seward Yacht Club, is still active. Over the years, the club has held many sailboat races; during the late 1960s, one of the more challenging races was the Summer Solstice meet, a 70-mile race that took contestants from Seward to the Chiswell Islands and back. [79]

With few exceptions (such as the boat races just noted), most of the boating and sportfishing activity that took place out of Seward from the 1940s through the 1960s was limited to Resurrection Bay. Very few boated or fished for pleasure in park waters. Known instances of such use are described below.

During World War II, the USO-SSO Activities Council (which organized recreational activities for soldiers) sponsored a series of boat trip outings, at least one of which entered park waters. In August 1944, it organized a free daylong trip to Aialik Glacier. Trips to other nearby features–Bear Glacier or the Chiswell Islands–may also have been sponsored during the war years. [80]

During the 1950s, the Fish and Wildlife Service wrote a special report on the Kenai Peninsula's fishery resources. The report noted that none of the bays or rivers in the present park ranked particularly high among the peninsula's sport fishing destinations. It did, however, state that in 1955, Resurrection River recorded 1,000 man-days of use by sport fishers, a volume that was exceeded by eleven other peninsula sport-fishing areas. [81]

In July 1961, the Bureau of Land Management classified hundreds of Alaska public land parcels as recreation and public purpose sites. These parcels, scattered throughout the state, were authorized by a Congressional act of June 14, 1926 and were available for disposal to "a state, territory ... or to a non-profit corporation or nonprofit association for any recreational or any public purpose." Within the present park boundaries, two parcels were classified by the BLM's action: a 900-acre parcel in the Bulldog Cove area, south of Bear Glacier, and an 80-acre parcel on the east side of Aialik Bay, just south of Coleman Bay. Available land records do not specify who may have been interested in the parcels, nor do they describe the parcels' intended land use. Lacking other evidence, it appears that the BLM probably offered the parcels to the State of Alaska. They were offered either to the Division of Lands for a future state park or recreation site or (less likely) to the Department of Fish and Game for fish management purposes. The interested party–whoever it was–soon learned that part of the Bulldog Cove parcel had previously been claimed by Raymond W. Gregory, who hoped to establish a fishing lodge on the property. Gregory, as it turned out, never developed his lodge plans, but the existence of his claim probably prevented the state from developing the site. Neither parcel was developed, and in January 1969 the two parcels were returned to the public domain. [82]

Sidney Logan, an ADF&G fisheries biologist, was posted in Seward in April 1961, largely due to the efforts of Seward Salmon Derby officials. In a recent interview, Logan recalled that Seward had four or five boats available for charter during the seven-year period he lived there; sportsmen normally did not fish farther south than Rugged Island, although they occasionally fished as far south as the Chiswell Islands. He noted that "hundreds of boats per summer visited the Kenai Fjords coast" during the years he lived in Seward. Logan was quick to point out, however, that "there was no sport fishing activity to speak of" in the fjords and that the amount of fishing was "insignificant" in comparison to either the Resurrection Bay silver salmon sport fishery or the Russian River sport fishery. Fishers sought out the waters of the future park for halibut, rockfish, and lingcod; so far as he recalled, no charter-boat operators consistently referred clients to locations in park waters. He did not recall any problems managing the park's sport fishery during this period. As to sightseers, Logan had no recollection of any; "there may have been some," he noted, "but I wasn't aware of it." [83]

Jim Rearden, who served as the Homer-based commercial fisheries biologist for ADF&G from 1960 to 1969, recalls that the waters of the future park supported much less activity than Logan had estimated. Rearden, who flew along the coast several times each year, stated in a recent interview that there were "virtually no sports fishermen" in the fjord waters during his tenure in that position. He recalled that the Seward boat harbor had "almost no sports boats before the [1964] quake" and that the waters in the fjords were too rough to allow sport fishing with the boats then available. [84]

Research by historian Mary Barry largely corroborates Logan's and Rearden's recollections. Barry noted that before 1960, Mark Walker's Breezin' Along was the only large boat in Seward available for fishing charters. (Several smaller boats also carried small numbers of paying fishermen.) During the early 1960s, there were approximately six charter boats; Jim Lawson and his wife started the Fish House during this period to coordinate fishermen and charter boats. The fishing fleet was largely wiped out in the 1964 earthquake, but a year later several charter boats were again available, the largest being the 83-foot Maxine, which carried 49 passengers. In 1968, a new company organizing fishing charters–Resurrection Bay Tours–commenced operations. Don Oldow, a veteran ship pilot, founded the company with his wife Pam. Beginning in 1974, the company began serving the fjord country. It thus played a key role in stimulating tourism to the fjord country, and it also assisted the NPS in its investigations of the proposed park unit. [85]

Ted McHenry, who moved to Seward as a sport fisheries biologist in 1969, recalls that there were "an odd few"–perhaps 20 boats per summer–that went into park waters during his first year or two of residence. Those few were operated primarily by Anchorage people who had "larger boats" moored at the Seward boat harbor. Most of those who sailed into park waters headed for Aialik Bay; others went to Harris Bay. McHenry felt that the boat owners, some of whom were veteran Resurrection Bay sports fishers, were attracted to park waters because they offered better opportunities to harvest halibut, salmon, rockfish, red snapper, black bass, and lingcod. [86]

If fishing and sightseeing were occasional activities in the future park during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, hunting appears to have been an even rarer activity. Little solid evidence has come to light regarding how much hunting has taken place. Prior to the mid-1960s, few sport hunters were willing to brave the fjord country's rough waters. Hunting pressure was slight for several reasons: the number of large mammals was relatively small, species such as Dall sheep and moose were unavailable, and the megafauna that inhabited the area–black bear and goats–could be harvested with less effort elsewhere. The only hunter known to frequent the outer coastal area during this period was Martin L. Goreson. Whether he hunted in the park is a matter open to debate.

Goreson, who hailed from New York, was one of hundreds of GI's who landed in Seward and served at Fort Raymond. After the war ended, he remained in town as a guard at the mothballed camp until October 1947, when the camp passed into private hands. Goreson then went into the guiding business, and in 1950 he heard about a Fish and Wildlife Service plan to transport goats from the Seward area to Kodiak Island. For two years, agency staff tried and failed to capture any goats; Goreson then stepped forward and volunteered. To the surprise of agency officials, Goreson was able to collect at least five mountain goats, more than enough to successfully initiate a Kodiak Island goat herd. [87] Several local wildlife experts have suggested that Goreson captured at least some of these goats within the boundaries of the present park. Available research, however, suggests that most if not all of his goat gathering took place either on the slopes of Mount Alice (northeast of Seward), near Day Harbor (east of Resurrection Bay), or at South Beach (near Caines Head). [88]

When a national park was being considered for the area in the early 1970s, the state (which favored the status quo) and the National Park Service (which backed a plan that would prohibit hunting) had widely divergent opinions on historical hunting levels. The state, citing the existence of an airstrip (built in 1965) at the head of Beauty Bay, noted that "the lands surrounding Beauty Bay have had a long history of seasonal use by hunters and fishermen because of ... its proximity to Homer." But NPS officials disputed that assertion and countered that "access [to the proposed park] for hunting is limited by the rugged terrain, weather conditions and general accessibility;" for that reason, "relatively few people would be affected" if a park was established. The agency noted that "the wild coastline and the lack of interest generally has kept sport hunting down. Harvest ticket counts ... show relatively low use." Citing ADF&G records for 1973, for example, the NPS noted that nine goat hunters had canvassed the coastline that year and bagged four goats. The NPS further noted that "only one full-time guide out of Seward hunts the fjord coast for mountain goat and black bear, the only two big game species represented in the proposal," and it was quick to point out that most of the guide's income was from non-hunting sources. [89]

In the Resurrection River valley, the NPS recognized that hunting opportunities were more favorable. A government report stated that "hunting of mountain goats also occurs [in the valley], where a few moose may also be taken." The state, however, closed the area along the newly constructed Exit Glacier Road in the early 1970s, probably to enhance wildlife viewing opportunities for tourists (see section below). It reportedly did so "at the request of the Seward Community who wished to encourage the viewing of unhunted wildlife in their natural habitats." [90]

Throughout the quarter-century that followed World War II, Seward itself was a relatively minor tourist draw. As noted above, the completion of the road to Anchorage made Seward accessible to rubber-tire travelers, and out-of-towners to an increasing degree flocked to Seward for the Fourth of July (for the Mount Marathon race and associated activities) and in August (for the Silver Salmon Derby). Except for those two events, however, the town had few tourist attractions. Seward promoters trumpeted that its Fourth Avenue had "the second brightest street in America" (only Chicago's State Street was brighter), and in the mid-1960s the town proclaimed itself the "Fun Capital of Alaska." Those claims, however, did little to change the town's overall perception; as a 1975 article noted, "When you mention Seward, most Alaskans think of a sleepy little town at the end of the highway." [91]

Oil Exploration and Kenai National Moose Range Management

One of the most significant events in Kenai Peninsula's history was the discovery of oil along the Swanson River, northeast of Kenai, in the summer of 1957. Because of the widespread period of oil exploration that preceded the find–and particularly because of the rush of activity that followed it–thousands of people descended on the Kenai, and thousands of acres of wilderness were converted to residential, commercial, and industrial purposes. Paradoxically, however, the only effect that this activity had on land in or near the present park was a blanket prohibition on oil and gas development. The following paragraphs explain how these developments were manifested.

As noted above, President Roosevelt had signed an executive order establishing the Kenai National Moose Range in December 1941. The range had remained intact and generally undisturbed during the war years; shortly after the cessation of hostilities, however, three privately-owned townships in the present Soldotna and Sterling areas were homesteaded and subsequently eliminated from the range. In 1947, a fire started by road workers destroyed 400,000 acres of wildlife and wildfowl habitat on the 2,000,000-acre range; on the heels of that fire, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service set up a headquarters for the range (in Kenai) and dispatched two men there to staff it. [92]

Before long, oil company representatives began to eye the range, and in 1952 seismic exploration began. Exploration, most or all of it taking place north of the Sterling Highway, continued at an increasingly hectic pace for the next several years, in large part because of the pro-development policies of Interior Secretary Douglas McKay. The frantic level of activity slowed in June 1956 when Fred Seaton succeeded McKay; Seaton halted any new oil and gas exploration until impact studies could be completed. But the pressure for development skyrocketed on July 23, 1957, when the Richfield Oil Company announced that one of its wildcat wells had struck a significant oil deposit more than two miles underneath a Swanson River moose pasture. [93]

|

| Map 10-3. Kenai Moose Range Boundaries, 1941-1971. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Interior Department was soon inundated with requests that would have opened most of the Kenai Moose Range to oil-development activity. Congress reacted to the pressure by holding hearings in Washington because it wanted to know how the agency could simultaneously protect wildlife and permit petroleum development. Those hearings took place in December 1957. In the face of such development pressure, all the agency could realistically hope to do was shield a reasonable portion of the area from petroleum development. Secretary Seaton, therefore, decided in late January 1958 to close approximately half of the range to oil and gas leasing "because such activities would be incompatible with the management thereof for wildlife purposes." [94] Seaton, however, did not issue a Secretarial Order with that language until July 24 (see Map 10-3). The order declared that most of the range's southern half–including all of the land in the high-elevation country overlooking Skilak and Tustumena lakes–would be off-limits to oil and gas leasing. [95]

Pro-development forces, both inside and outside of government, demanded that Seaton open up more of the moose range to oil development. The agency, worried about a sharp drop in the area moose population, initially refused to budge. Eventually, however, the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (part of the Fish and Wildlife Service) agreed on a land swap with the Bureau of Land Management and the Alaska Division of Lands. The various agencies agreed that the boundary realignment was "necessary in order to facilitate administration of the Range and as a basis for the survey of adjoining selections by the State of Alaska." The land trade entailed the removal of 310,000 acres of existing refuge land–most of which lay on the Harding Ice Cap and thus had low wildlife values–and added 40,115 acres of land in the Caribou Hills, adjacent to the refuge. On May 22, 1964, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall signed a Public Land Order that codified the land swap. The 270,000-acre reduction was not enough for the Alaska Congressional delegation, which attempted to eliminate another 270,000 acres. (Senator Ernest Gruening, part of the delegation, went so far as to urge that the entire moose range be returned to the public domain.) That move, however, was squelched, and the boundaries that were established in 1964 remained until the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in December 1980. [96]

The agency's early plans for the refuge (and in particular its plans for the Kenai Mountains portion of the refuge, adjacent to the present national park) were by necessity inseparable from the ongoing, petroleum-dominated political atmosphere. Agency officials nevertheless recognized that the range's ecological diversity demanded two different management objectives. Biologist Will Troyer, who wrote an early management document for the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (BSF&W), stated that the refuge had been created to "support large populations of moose, as well as quality trophy animals." The lowlands, he noted, were managed for high moose populations. The range also, however, had more than 500,000 acres of "spectacular mountain country" that the agency planned to manage for "trophy purposes and high quality hunting enjoyment." He recognized that nearly all hunting in the refuge took place in the lowlands. The managing agency, however, was also "obligated to manage a portion of this area for trophy animals," particularly of Dall sheep. [97] Because most hunting pressure took place in the lowlands, the agency had a largely laissez faire attitude toward the higher elevation areas of the refuge; so far as is known, it conducted no research projects in the highlands portion of the moose range.

During the 1960s and on into the 1970s, the BSF&W's management attitude toward the southeastern portion of the moose range remained consistently protective. In February 1960, for example, the agency released a recreational management plan for the refuge. The plan stated that "a management approach forcefully directed at a wilderness concept is required to preserve a resemblance [sic] of natural conditions caused by the inevitable forces of progress." The plan proposed numerous recreational improvements for the refuge, but none in the southeastern uplands. [98] In April 1971, the Fish and Wildlife Service released a wilderness plan for the refuge; it proposed more than a million acres of wilderness, including a huge Andy Simons Wilderness Unit encompassing all of the refuge's high country. (Simons, at noted above, was a famous, long-time guide who had died just a few years earlier.) [99] That plan was not implemented. Most of the acreage in the Andy Simons Wilderness proposal, however, became congressionally designated wilderness nine years later with the passage of ANILCA.

The Exit Glacier Road

As noted in Chapter 5, Seward citizens had been lobbying off and on since the 1920s for a road that would connect Seward to the Cooper Landing area via the Resurrection and Russian River valleys. Neither Federal nor state funding authorities had ever seriously considered these proposals. The completion of the Sterling Highway, and the connection of the Kenai Peninsula road network to Anchorage, largely negated the need to build such a road. But road-based tourism, which consistently increased during the 1950s and early 1960s, spotlighted the need to develop new area attractions, and the devastation wrought by the 1964 earthquake underscored the critical need to diversify Seward's economy. Herman Leirer, whose family had operated the local dairy since the mid-1920s, was acutely aware that far too many people "drove down the highway into town, then turned around and headed back because there wasn't anything to do." [100]

Leirer, Jack Werner, and other residents felt that "Resurrection Glacier," eight miles northwest of town, would be an excellent new sightseeing destination. In order to access the glacier, they decided to build a road there. By October 1965, they had convinced Seward City Manager Fred Waltz and the city council to take up the cause; they, in turn, organized a committee to complete the seven-mile access road. Many Seward residents, including some of the trainees at the local Skill Center, immediately set to work; the city helped by loaning them graders, loaders, and other equipment. Work continued until cold weather forced a cessation of activity. The following year, work was furthered by a grant from the Alaska Purchase Centennial Commission; efforts continued throughout the warmer months, primarily on weekends. [101]

Work continued at a slower pace until 1970. By that time, four miles of road had been roughed out and the state had expended $58,000. In July 1970, Governor Keith Miller announced that the state would provide an additional $125,000 for road construction; this was intended to be sufficient to complete the road. By the end of the 1971 construction season, a gravel road that was "generally too rough for many passenger cars" had been largely completed from Seward Highway to the east bank of the Resurrection River. West of the river, a 1.75-mile road was bladed out in 1970 between the river and a site 0.2 miles east of Exit Glacier. All that was needed to complete the 9.3-mile road between Seward Highway and the glacier was the construction of two bridges, one of them over the Resurrection River. [102] A decade, however, would pass by before a pedestrian bridge was constructed, and another five years would elapse before vehicle access to the Exit Glacier area was a reality. [103]

Few tourists traveled the rough, unpaved road during the 1960s or 1970s. One user group, however, was the U.S. military. Since 1950, Seward had been home to an Army Recreation Center; the center's primary purpose was to provide deep sea fishing opportunities for troops from Whittier and Fort Richardson. But in 1970, the recreation center–and the Exit Glacier road–became part of rigorous outdoor training program. Twice a week, fifty-man platoons from Fort Richardson were dropped off at the Kenai River-Russian River confluence; from there, they hiked up the trail to Upper Russian Lake, then bushwhacked over the drainage divide and down the Resurrection River valley to the road terminus near Exit Glacier. The four-day hike gave the soldiers practice in survival, patrolling, camouflage, land navigation, and communications. It is unknown whether the military conducted these hikes in other years. [104] The Resurrection River valley remained isolated until the 1980s, when crews under contract to the U.S. Forest Service completed a 16-mile trail that connected the Exit Glacier road with the Russian Lakes trail. [105]

Mountaineers Explore the Harding Icefield

As noted above, Seward residents generally ignored the huge icefield west of town before 1922. The construction of the Spruce Creek trail that year, however, made it possible to view the upper portions of the icecap, and President Harding's promise to visit the territory was sufficient to bestow his name on the feature. Between the mid-1920s and the early 1930s, the increasing popularity of aviation had given a lucky few the opportunity to soar over the icefield. Up to this point, however, people had walked only on the icefield's margins. [106]

In early 1936, a 27-year-old Swiss immigrant named Yule Kilcher disembarked in Seward. He was headed for Kachemak Bay, where he intended to take up residence, but he was so intrigued by the icefield he had seen from the steamship that he vowed to cross it before long. Unwilling to wait two weeks for a coastal steamer, Kilcher walked to the Homer area, probably by way of the Resurrection River valley. After securing a homestead, he returned to Seward, and in late July he hiked up the Lowell Creek drainage toward the icefield. Conditions on the icefield overwhelmed him, however, and a week later he was back in Seward. [107]

About 1940, two Kenai Peninsula residents, Eugene "Coho" Smith and Don Rising, apparently were successful in their attempt to cross the icefield. They hiked from Bear Glacier west to Tustumena Glacier. The men, however, told no one of their intentions, and once they returned, Smith's wife was the only one that was aware of what they had done. Their trip remained a virtual secret for more than twenty years after they completed it. [108]

Two parties attempted to cross the icefield in the mid-1960s. In 1963, a party consisting of Don Stockard, Tom Johnson, and Carl Blomgren tried a westbound crossing. Three years later, J. Vin Hoeman, Dave Johnston, and Dr. Grace Jansen made an eastbound attempt. Both attempts were unsuccessful. [109]

In the spring of 1968, the first documented mountaineering party succeeded in crossing the icefield. Ten people were involved in the crossing, which went from Chernof Glacier east to Exit Glacier. Expedition members included Bill Babcock, Eric Barnes, Bill Fox, Dave Johnston, Yule Kilcher and his son Otto, Dave Spencer, Helmut Tschaffert, and Vin and Grace (Jansen) Hoeman. As noted above, Yule Kilcher, Dave Johnston, Vin Hoeman, and Grace Hoeman were veterans of previous attempts; of the ten, only four–Bill Babcock, Dave Johnston, Yule Kilcher, and Vin Hoeman–hiked all the way across the icefield. The expedition left Homer on April 17, bound for Chernof Glacier; eight days later, they descended Exit Glacier and arrived in Seward. Along the way, the party made a first-ever ascent of Truuli Peak, a 6,612—foot eminence that protrudes from the northwestern edge of the icefield near Truuli Glacier. [110]

|

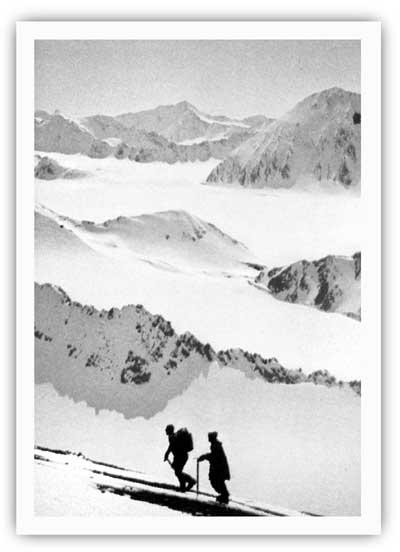

| Eric Barnes and Helmut Tschaffert during their ascent of Truuli Peak in April 1968. David Spencer photo, Alaska Magazine, May 1971, 47. |

|

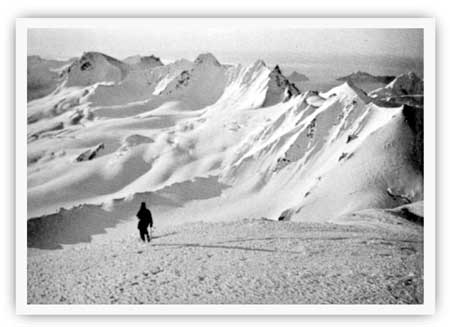

| Bill Babcock looks out from a nunatak on the morning of April 25, 1968. Dave Spencer photo, Alaska Magazine, May 1971, 46. |

After the 1968 success, the icefield was crossed with increasing frequency. The Seward newspaper reported that two parties crossed during the summer of 1970, and during the early 1980s an NPS report stated that "1 to 2 Harding Icefield expeditions per year have taken place over the last five years." Most of those traverses began at Exit Glacier and ended in Homer. [111]

The Harding Ice Field Snowmobile Development

During the 1960s, when mountaineers were showing an increasing amount of interest in crossing the Harding Icefield, local entrepreneurs were beginning to envision the commercial possibilities of taking tourists up to the icefield on short-term excursions.

Commercial interest in the icefield apparently began in the spring of 1966 when Seward resident William C. Vincent made his first visit. Vincent, who ran a plumbing and heating shop, had lived in Seward since 1950; he was a Chamber of Commerce member and a two-term city councilman. [112] Vincent quickly became enthusiastic about the icefield; by January 1967, he had assembled a four-person development team and publicized a five-year icefield development scenario. As his granddaughter later noted, the team "proposed to make the Harding Icefield a visitors resort with glacier skiing, snowmobile tours, summer ski racing camps, mountaineering, outward bound camps, and cross-country ski touring." The first development project would be the construction of a small dock at Bear Glacier. [113]

|

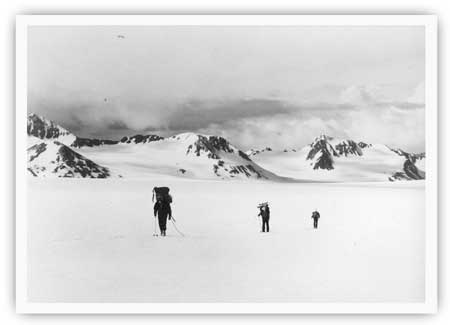

| A trio of skiers crossing the Harding Icefield during the 1970s. M. Woodbridge Williams photo, NPS/Alaska Area Office print file, NARA Anchorage. |

Vincent's development project was never realized, but others shared his dreams and decided to act. Jim Arness, who operated a snowmachine rental shop in North Kenai, "dreamed up" the idea of establishing a snowmobile touring operation on the icefield near Seward. He therefore teamed up with Joe Stanton, the head of Harbor Air Service, and in the summer of 1969 the two constructed a "shack" on the icefield–reportedly "somewhere near the headwaters of Exit Glacier"–and brought three ski-doos up to the site. The operation that year apparently lasted for only a short time; snows that autumn came so quickly that both their building and one snowmachine were buried before they could be removed. The items were never recovered. [114]

Undaunted, the pair returned the following spring and began constructing a 16' x 20' equipment shed and warming hut. Soon afterward, they flew ten ski-doos (nine single-tracks and one double-track) and three ski-boos (sleds) up to the icefield. [115] In May, amid much fanfare, local residents and tourists began flocking to the site; some came to ride the snowmachines, but others wanted to ski, snowshoe, or merely sightsee. By early June, approximately 100 people had been flown up to the icefield, and by late July an estimated 200 to 300 had made the trip. To judge by contemporary accounts, reaction to the operation was overwhelmingly positive; local resident Dot Bardarson noted that her flight and snowmachine ride was "the best $70 I ever spent." The project's backers, sensing that it would be a long-term success, laid plans to increase the size of their operation. They envisioned a $1.5 million construction project that would include a gondola lift system (to take people to the top of Exit Glacier), a summit station, a lower terminal, and a T-bar lift near the warming hut. [116]

But in early July 1970, the operation hit a major snag when Bureau of Land Management officials in Anchorage read newspaper accounts about it. They quickly learned that the operation was being held on BLM land–and thus needed an agency-issued Special Land Use Permit–but Arness, the operation's organizer, had not applied for one. Making the situation far murkier was Interior Secretary Stewart Udall's 1966 land freeze order. This action withdrew the Harding Icefield (along with most of Alaska's unreserved public land) from entry; as a result, Arness would not have been approved for a permit even had he applied for one. BLM official Sherman Berg drove to Kenai on July 9 and discussed the matter with Arness; Berg personally expressed hope that a satisfactory resolution could be worked out, but he could promise nothing. Meanwhile, the agency handed Arness a tresspass injunction. He was given thirty days to quit his operation and vacate the area. [117]

Seward area residents, predictably, were saddened by the BLM's decision. The Seward Phoenix Log, in an editorial, said "Let us hope that something can be done to see that the Cap development continues–it means a lot to Seward and the rest of the Kenai Peninsula." H. A. "Red" Boucher, who was running for governor at the time, visited the icefield on July 20; he vowed to keep it open and wrote a lengthy letter to BLM officials protesting the planned expulsion. [118]

The actions of Boucher, Arness, and local officials gave the operators a little breathing room; the operation's deadline to vacate was extended from August to November. But on the larger question, the BLM could not budge, perhaps because of the precedent that such an action would have had on other Alaska public lands. Given that scenario, the operation continued in business until September 1970, perhaps later. The operators, however, were forced to leave so quickly (perhaps because of a heavy, late-season snowstorm) that, as in 1969, they left their warming hut in place where it was engulfed by the winter's snowfall. As for the snowmobiles, several more were lost. One account states that two were buried near the warming hut, while another avers that the operators attempted to drive three off the icefield but became stuck in the crevasses of Bear Glacier. [119]

Bill Vincent, who fully supported the Arness-Stanton operation, refused to give up. He recognized that the icefield was an attraction that "would offer something strangely unique to visitors regardless of where they may have come from." Comparing the area to Columbia Icefield in Canada's Jasper National Park, he furthermore noted that the icefield could be put to any number of uses, including "a military testing area for arctic equipment and survival and an international type hotel." As late as February 1971, he wrote that his group "still plan[s] on seeking private capital to develop the field." [120] The continuing land freeze and the long battle over Alaska's national interest lands, however, prevented any such plans from being implemented, at least in the short term.

One positive spinoff of Vincent's publicity and the Arness-Stanton operation was a revival of interest in Seward-based tourist flights over the icefield. As noted above, flights over the icefield had been advertised, primarily to Seward residents, for short-term periods in both the 1920s and 1930s. In the decades that followed, some tourists doubtless arranged for overflights with Seward- or Homer-based pilots. But no one, so far as is known, advertised such a service. Beginning in 1970, however, the Milepost–a well-known tourist publication–began to advertise the beauty of the Harding Ice Cap in its Seward section and also urged tourists to see the Ice Cap "via charter plane trips." This verbiage, often accompanied by advertisements from local air taxis, remained in future Milepost issues as well as in other local promotional literature. [121]

kefj/hrs/hrs10b.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002