|

Kenai Fjords

A Stern and Rock-Bound Coast: Historic Resource Study |

|

Chapter 10:

RECREATION AND TOURISM (continued)

Visitors to the Southern Kenai Coast,

1900-1940

Early Sightseers and Hunters

Both sightseers and hunters have been attracted to the Seward area since the earliest years of the twentieth century. Tourists, to be sure, were few and far between during the first decade after Seward's founding. Most of the visiting hunters, moreover, were merely passing through on their way to the western gamelands.

Seward's earliest residents were well aware of Resurrection Bay's tremendous scenic attributes, and less than a year after the town's founding, the bay was being used for recreational sailing trips. [25] These trips probably continued, on an intermittent basis, for years afterward.

Relatively few people sailed along the outer coast during the twentieth century's first decade, but some of those that did were well aware of its scenic beauty and tourist potential. Ulysses S. Grant and D. F. Higgins, Jr., two government geologists, sailed the Kenai coast in 1909 and were thunderstruck at what they saw. In a 1913 monograph they wrote, "It is hoped that this publication may attract attention to some of the most magnificent scenery that is now accessible to the tourist and nature lover." [26]

During this period, Alaska tourists were seldom seen outside of the southeastern "Inside Passage" route, and those who sailed "to the westward" were a rare sight indeed. The decision to build a government railroad, and the line's subsequent construction, however, took place at the same time in which tourists were showing an increased interest in Alaska as a destination. As a result, tourism became increasingly evident in Seward and other southcentral ports during the years that immediately preceded World War I. Beginning in 1912, the Alaska Steamship Company advertised trips into the area. The advertisements apparently met with some success, and when the Pacific Steamship Company–the successor to the Pacific Coast Steamship Company–began operations in 1916, it too advertised for tourists. The World War I years were particularly successful for Alaska tourism because European travel was prohibited. Thus, it is highly likely that an increasing number of tourists during this period visited Seward, Kodiak, Seldovia, Anchorage, and other southcentral ports. [27] The route for some of these ships–both from "Alaska Steam" and from "the Admiral Line"–undoubtedly paralleled the outer Kenai coast. The route for the large steamships, however, took passengers on a more southerly route, away from the coast. Clouds and storms, moreover, often obscured the view. For these reasons, the few tourists who may have been aboard these ships saw only an occasional, distant glimpse of the outer Kenai coast. [28]

Hunters were also attracted to the area. As noted above, hunters from around the world passed through Seward each spring and fall on their way to the famed western Kenai gamelands. But others hunted locally. In February 1907, lands within the present park received favorable publicity when an article by local hunter Edwin Lowell was published in Recreation Magazine. The article concerned a moose hunt that he and a fellow Sewardite had taken "around the head of the Resurrection River" the previous September. [29]

Hunting was a popular pastime among Seward residents, and in October 1910 sufficient numbers of them gathered to organize the first of several "big game hunts." In this activity, local hunters were divided into teams; the teams received points according to the species of game that they obtained during the restricted time of the contest. Upon hearing of the contest, eastern big game hunters howled in protest, fearing a wholesale slaughter of game. The protesters were told, however, that the participants all adhered to the game laws and that all meat obtained was either consumed or put into storage for future use. The Seward Outing Club, which may have been an outgrowth of those hunts, was well established by 1914; it was one of a series of organizations that had been formed in the early twentieth century in towns along the southcentral Alaska coast. [30] Available evidence suggests that the vast majority of hunting by Seward residents during this period took place within a few miles of town or near the railroad right-of-way. As has been detailed below, an insignificant amount of sport hunting took place within the present park boundaries.

Rockwell Kent's Visit to Renard Island

|

| Rockwell Kent, a budding author and artist, spent the winter of 1918-1919 at a fox and goat farm on Renard Island in Resurrction Bay. Current Biography, 1942, 447. |

In August 1918, a relatively obscure writer and illustrator named Rockwell Kent and his nine-year-old son sailed into Seward and checked in at the Sexton Hotel. The elder Kent, aged 36 at the time, had studied architecture and art; upon leaving school, he became an adventurer. When he arrived in Seward, he was not a tourist. Instead, he came to Alaska, in part, because he was a free-hearted spirit. And because he loved German literature and culture, he also sought a refuge from the jingoistic, anti-German sentiment then rampant in the United States. In addition, he noted,

I came to Alaska because I love the North. I crave snow-topped mountains, dreary wastes and the cruel Northern Sea with its hard horizons at the edge of the world where infinite space begins. Here skies are clearer and deeper and, for the greater mystery of those of softer lands. [31]

More specifically, Kent chose to visit Seward because he "did have a love for the isolation and wonder of island life," and he ideally sought a location "that combined the quiet dignity of the primitive forest with the excitement of the ever-changing ocean." [32]

He found such a location soon after he arrived. While rowing in the bay, he and his son met a 71-year-old fox and goat farmer named Lars Matt Olson. During the course of their conversation, Olson invited the two to visit him on Renard (Fox) Island, and on August 28, the two moved into a cabin near Olson's residence. Kent and his son remained on the island for more than seven months; the elder Kent spent much of that time writing, drawing, and enjoying a simple, primitive existence. The illustrated narrative of his experience, which he called Wilderness; A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska, was Kent's first published book–and one of his best. The New York Times called it a "very beautiful and poignant record of one of the most unusual adventures ever chronicled;" it has also been called "a unique book and [an] unrecognized classic in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau's Walden." The woodcuts with which he illustrated the volume were notable as well; the public reportedly "gobbled up his work" when it was exhibited in New York. One biographer has noted that "With the appearance ... of his 64 Alaska drawings, Kent suddenly became one of the top-notch illustrators. His illustrations, in subsequent years, ... have become collectors' items." Critics also praised the book for its deft interplay of text and illustration; according to Frank Getlein, "many critics consider [Wilderness as one of] the best American books ever produced in terms of harmonious balance between text and pictures." [33]

|

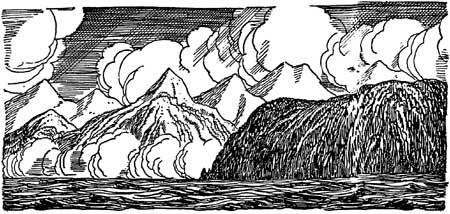

| Illustration by Rockwell Kent from his book Wilderness: A Journal of a Quiet Adventure in Alaska, 1920. Courtesy The Rockwell Kent Legacies. |

Kent appears to have savored his life on Renard Island during most of his sojourn, and he wrote extensively about the snow, wind, cold, isolation, and other elements of his immediate surroundings. The book made no attempt to soft-pedal the surrounding climate and topography, elements that were far more similar to the fjord country to the west than of Seward and the surrounding railbelt. (Caines Head, for example, was "a merciless shore without a harbor or tending place;" Bear Glacier was a place from which "the winds blow forever fiercely and ice cold;" and Renard Island itself was "warmer and much wetter [than Seward], and even the wind blows there when Seward's waters are calm.") Kent, during his stay, never ventured within the boundaries of the present park; the closest he came was a yearning to visit Bear Glacier that manifested itself during a visit to nearby Sunny Cove. He did, however, complete paintings of the present park coastline; one features Bear Glacier, while another looks from Renard Island toward Resurrection Bay's western shore. [34]

Kent, artistically and spiritually, appears to have embraced his experience on the island. Shortly after leaving, he exulted, "Know, people of the busier world, that there on that wild island in Resurrection Bay is to be found throughout winter and summer the peace and plenty of a true Northern Paradise...." [35] The popularity and the positive tone of Kent's reminiscence, however, did not result in increased tourism to either Alaska or the Seward area, for two reasons. Kent's book, successful as it was, appealed primarily to a small, literary audience. [36] In addition, almost everyone that visited Alaska during this period demanded the modern-day amenities that steamship travel provided; tourists thus had little interest in emulating Kent's strenuous, primitive experience.

Renard Island, and other points in southern Resurrection Bay, were fairly popular visitor destinations both before and after Rockwell Kent spent his winter there. Several visited the island, either on day trips or on overnight camps, while others sailed "down the bay" without disembarking. Several Sewardites, to be sure, paid social calls on Kent (and Olson) during the winter of 1918-19, but few latter-day tourists were so captivated by Wilderness that they felt the need to visit the island where they had resided. The cabin in which Kent and his son lived eventually collapsed. Today, there are almost no physical remnants of the cabin where the Kents stayed, and a tourist lodge was built in the mid-1990s on the Olson cabin site. [37]

Seward Becomes a Tourist Node

After World War I, the Alaska tourist trade boomed. The number of tourists increased almost every year from 1918 (when the war ended) through the late 1920s. Although there area few statistics that describe the industry during this period, the number of tourists that sailed to Alaska each year probably doubled, and may have tripled, during the decade that followed the cessation of World War I.

One of the most dramatic tourist growth areas was southcentral Alaska. Prior to the war, the only maintained routes in the region were the Valdez-Fairbanks Trail, the Copper River and Northwestern (CR&NW) Railroad, the Alaska Northern Railroad (which operated, on an intermittent basis, for only 72 miles), and a broad network of sled roads and winter trails. But by 1919, the trail between Valdez and Fairbanks had been improved into the Richardson Highway; and, as noted in Chapter 5, the U.S. government purchased the Alaska Northern line and extended the railhead hundreds of miles northward. With the exception of a bridge over the Tanana River, the so-called Alaska Railroad was completed all the way to Fairbanks in early 1922. Most tourists, however, did not begin to travel over the line until the summer of 1923. [38]

The completion of the line gave the prospective visitor to southcentral and interior Alaska an increasing variety of tour choices. A few tourists, as before, remained on board the coastal steamers, disembarking only for day trips in the vicinity of ports. Most people, however, chose to head inland. Tourists opting for a short trip inland disembarked in Cordova, took the CR&NW north to Chitina, boarded an auto stage and rode to Willow Creek on the Richardson Highway. They then continued on to Thompson Pass and Valdez, where they resumed their steamship journey. [39]

Those opting for a longer trip in southcentral and interior Alaska chose the Golden Belt Tour. Passengers on this tour rode the CR&NW north from Cordova to Chitina, where an auto stage awaited them for a trip north to Fairbanks. (Others began their inland trip in Valdez and took an auto stage all the way to Fairbanks.) Once in Fairbanks, tourists boarded the recently completed Alaska Railroad and rode south to McKinley Park, Anchorage, and Seward. Some tourists took this tour in reverse order; in either direction, it was a popular tour for almost twenty years. Those who wanted to avoid the travails of the Richardson Highway opted for the All-Rail Tour, an excursion on the Alaska Railroad from Seward to Fairbanks and return. [40]

Those who hoped to see the north country in a more leisurely manner–and could afford to do so–chose the Grand Circle Tour. Tourists taking this tour package disembarked at Skagway, rode the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad to Whitehorse, and sailed down the Yukon River on a WP&YR boat to Dawson. From there, tourists continued down the Yukon on an Alaska-Yukon Navigation Company steamer to Tanana and Fairbanks, and then rode the Alaska Railroad south to Seward. This tour required more than three weeks of inland travel. It could be taken in reverse order as well, although that option was longer (and more expensive) because of the slower pace of upstream travel. [41]

Because it was a leading Alaska port, Seward had been dealing with visitors ever since its founding. Hunters, most of whom hailed from Outside points, had been streaming through town for years; they used local accommodations, and some of them bought their outfits in Seward as well. The spate of tourists that invaded after World War I, however, had different needs and expectations than any previous group; they made local citizens aware, many for the first time, of the area's tourist attractions and facilities.

Seward residents, to be sure, had been enjoying outdoor pastimes for years; available activities included bear and moose hunting, berry picking, water sports, picnicking, vacation cabins, and mountaineering. Tourists, however, were less willing to "rough it" than locals, and most needed guides and a large-scale form of transportation. But because tourism was such a minor industry, the only local tour was a rail excursion north to Kenai Lake, which had been offered on an intermittent basis (to hunters and fishermen as well as tourists) since the days when the Alaska Northern operated the line. [42] By the early 1920s, tourists were also given the option of taking an auto stage north on the as-yet-uncompleted road to Kenai Lake.

In 1922, Seward development interests investigated a new way to stimulate local tourism. Before this time, local residents had ignored the huge, unnamed ice cap located west of the city. But in March 1922, it was announced that the "monster glacier near here" would "be used as an attraction for tourists this summer." In order to stimulate interest, the Seward Gateway asked local residents to name the feature. One suggested that it be named after Warren Harding, the current chief executive. Harding had made no secret of his interest in Alaska; he had publicly expressed his interest in visiting the territory as early as April 1921 and still planned to do so. Gateway editor E. A. Rucker therefore concluded that "some honor could be shown him by naming this great glacier after him." By April 1922, someone in Seward–perhaps Rucker himself–had decided on the name Harding Icefield. [43]

At first, locals were given few hints about how the nearby ice cap would become a tourist attraction. But in late April, acting mayor Harry E. Ellsworth announced that local businessmen would fund the construction of a trail from Seward south to Lowell Point, and from there up Spruce Creek. The trail would continue over the drainage divide to the eastern edge of Harding Icefield. Promoters felt that the so-called Spruce Creek Trail would have economic benefits because at its terminus, "one hour and fifty minutes walking time" from Seward, tourists could "actually stand on a glacier and be carried across the great body of snow and ice in dog teams. [This would be] a novelty they cannot enjoy anywhere else in the summer time," an attraction that would "prove a great drawing card for tourists." [44]

Local resident Eric Nelson began constructing the trail in mid-July, and by August 12 the trail was complete. Several hikers assayed the route that summer, at least as far as the drainage divide. [45] By all accounts, the trip was awe-inspiring. Local resident D. C. Mathison, who ascended the trail in late July, positively gushed about the glacier as viewed from the ridgeline:

But it is to the west, that ever mysterious west, [where] the greatest attraction lies. Near at hand are deep gorges, glacier-torn mountains, heaved and twisted ridges, smooth and placid lakes, whose shores when not covered with snow are literally strewn with vari-colored stones and pebbles.... In the not too great distance is the vast expanse of Harding glacier.... I am perfectly sure that anyone obtaining a view under the ideal conditions which obtained when I was there, whose very soul was not stirred, who fails to bow in humble acknowledgement of the puniness and insignificance of man, is bereft of one of Nature's greatest gifts — appreciation! Its gigantic size, its monstrous shape, its forbidding appearance, whose frigid bosom only the most rugged and uncompromising peaks have dared to defile.

But I am wasting time in attempting to describe. You should have been where I sat, have this great panorama before you, which to be appreciated must be seen. Only a geologist could tell what has caused the topsy-turvy appearance of the whole country. None but an artist could, with the delicate strokes of his brush and the blending of his colors, do justice to its beauty. No one but a poet endowed with the descriptive language of Shakespeare, the weird imagination of Poe, the rollicking language of Burns or the wholesome simplicity of Edgar Guest, could describe its wonders and its beauties. [46]

The trail remained in use for years afterward. By the spring of 1924 a shelter cabin had been built at the trail summit. That summer, local resident Jo Hofman "arranged dog sled rides ... so tourists could enjoy a unique outing on the glacier." There is little evidence, however, that tourists braved the long, steep trail to ride on dog sleds. Most of those who hiked up the Spruce Creek Trail, in fact, were probably local residents; after 1926, tourist materials no longer advertised the trail. [47]

A more popular way to ascend the slopes west of Seward was the Mount Marathon trail. Since 1916, Mount Marathon had been the site of a July 4 race; a few participants each year, all from Seward, had scrambled up the slopes to Race Point before sliding and tumbling back into town. With the growth of tourism, however, locals began to recognize that non-racers would also like to ascend the mountain because it offered the climber a magnificent view of the town, Resurrection Bay, the outer islands, and the nearby mountains and glaciers. In June 1925 a visitor from Seattle, Ben Poindexter, suggested that he and a group of volunteers blaze such a trail. A trail up the face of the mountain was roughed out that year; it proved popular, both with visitors and local residents. [48]

During the 1920s, many Seward-area tourist attractions were developed in addition to the two trails noted above. In November 1923, for example, the road from Seward to Kenai Lake was completed, and in the years that followed, many Seward visitors took the half-day excursion out to Kenai Lake. [49] In downtown Seward, civic authorities established a waterfront park; complete with fountains and a Russian cannon, its purpose was to ensure that "visitors would find a pleasant scene when arriving by ship or train." Seward residents were proud of the new tourist amenities. Historian Mary Barry notes that on some sunny summer days during the 1920s, "Seward was practically deserted ... as beautiful weather lured the residents to the forests–some to hike the Spruce Creek trail, others to climb Mount Marathon, and the rest to motor to Kenai Lake." [50]

In the summer of 1923, Seward was briefly in the world spotlight when President Harding visited the port as part of his Alaska tour. On July 13, Harding arrived in Seward on the Navy cruiser Henderson; he mingled briefly with the townspeople, then headed inland on a waiting train. At Nenana, he paused long enough to tap in the "golden spike" commemorating the Alaska Railroad's completion (a feat that had been accomplished several months before), then continued on to Fairbanks. By July 17 he was back in Seward; two days later, the presidential party steamed down the bay and headed toward Valdez. [51]

|

| In July 1923, President Harding and his wife visited Seward. Harding is shown in a light-colored coat at the top of the gangway; his wife is in front of him. Neville Public Museum, photo 5658.4 |

Beyond the publicity it shed on Alaska in general and Seward in particular, the trip was notable to the project area in several respects. Harding was particularly impressed with both Seward and Resurrection Bay. He called Seward "a rare gem in a perfect setting." As to the bay, Governor Scott Bone advised Harding that Alaskans wanted to bestow his name on some physical feature. Bone suggested naming a glacier or mountain after him, but Harding, after entering Resurrection Bay, told him that "of all the beautiful scenery and interesting objects we have passed, I would rather have this entrance perpetuate my name than anything else I could imagine." Within an hour, Bone issued a proclamation naming it the Harding Gateway. [52] In addition, the Seward Gateway named the huge icefield west of town in his honor (an action that, as noted above, had first been accomplished several months earlier). Harding himself probably saw no more of the icefield than a glimpse of Bear Glacier, but the Henderson crew saw the icefield in greater detail. The crew spent several days in port while the President's party toured the Alaska interior; on one of those days, local resident Mel Horner guided the crew, a few townspeople, and several tourists south on the newly-constructed Spruce Creek trail. Judging by contemporary press reports, the party hiked to the watershed divide and continued all the way to Harding Icefield before returning to town. [53]

The Alaska Railroad, in conjunction with the various tour packages, developed several Seward-based tourist excursions during this period. In 1926, it revived its Kenai Lake rail tour, using as its northern destination a visit with Nellie Neal Lawing at the Lawing wildlife museum. That same year, rail tourists were given the opportunity to take a day trip to Spencer Glacier, 52 miles north of Seward; the glacier here was within easy walking distance of the train. And in 1927, tourists on a two-day Seward layover were given an opportunity to visit Anchorage. The popularity of these excursions was mixed. The Lawing excursion lasted until 1931, and the Spencer Glacier trip remained until 1935. These two side trips, and the Anchorage excursion as well, had the practical effect of diminishing prospects for Seward-area tourism development. [54]

Relatively few Alaska tourists prior to World War II traveled independently (that is, apart from an advertised tour package). For that reason, relatively few out-of-state tourists had more than a few hours' free time while in Seward. Despite that limitation, it appears that some tourists, as well as some Seward-area residents, enjoyed taking boat trips on Resurrection Bay. In 1923, for example, local resident Howard Long advertised his motor boat as being available "for hunting or pleasure trips." The following spring, an article advertised boat trips on the bay for tourists, and a self-styled vacation guide issued in August 1926 urged Seward visitors to "take a motor boat ride to Fox Island." [55] In all probability, small numbers of visitors, primarily from Seward, continued to take Resurrection Bay boat rides each summer from the mid-1920s through the late 1930s.

|

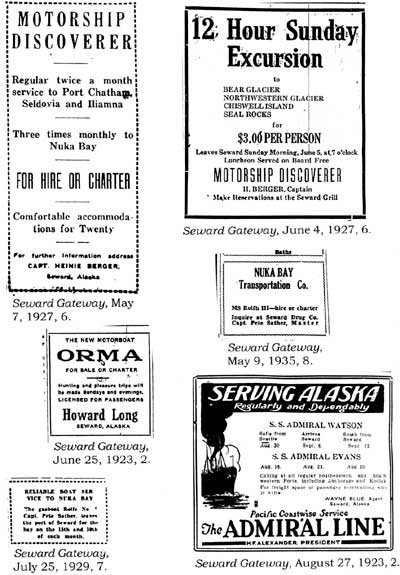

| Advertisements such as these lured early adventurers to the fjord country. |

Tourists and Hunters Visit the Coastal Fjords

As noted above, visitors have been passing through Seward ever since the town's founding in 1903. Hunters, furthermore, have been prominent since early days as well; Outside hunters headed through town on their way to Kenai Lake and the western Kenai gamelands, while Seward residents hunted on the outskirts of town and north within a few miles of the road or railroad. So far as is known, tourists and hunters prior to World War I largely ignored the southern reaches of Resurrection Bay, and virtually no recreationists spent time within the present park boundaries.

The first known recreational visit into park waters ended in tragedy. In October 1917, William G. Weaver and Benjamin F. Sweazey, the latter a licensed game guide, headed toward Aialik Bay on a bear hunt. When they did not return as scheduled, search parties were formed. Before long, the men's boat was found, bottom up, near Bear Glacier. No trace of the men was ever located. [56]

Over the next few years, a few Seward residents began to hunt in the coastal fjords. Charles Emsweiler, a local guide whose reputation was well established by 1913, took clients to the western peninsula gamelands. On his own, however, he hunted in a wide variety of locales, and in June 1919 he and his wife concluded a hunt in Nuka Bay, where they harvested three black bear. Three years later, the couple repeated their adventure. [57]

During the early to mid-1920s, occasional hunting parties–perhaps just one per year or even fewer–hunted within the present park boundaries. In May 1921, for example, local resident Jack Matsen headed down to Bear Glacier on what turned out to be an unsuccessful bear hunt. Two years later, the Gateway noted that "a party composed of Mrs. J. H. Flickinger, Andy Simons and wife, Frank Revelle and Milton Noll left today for down sound points where they will engage in a bear hunt." Occasional hunters also headed up into the Resurrection River valley; in August 1920, three Army privates ascended the valley at least as far as Redman Creek. [58]

Tourists–that is, recreationists who were not interested in hunting–were not known to frequent the present-day park until the mid-1920s. In August 1923, local residents Earl Mount and Mr. and Mrs. Otto Schallerer reportedly spent a pleasant Sunday on a boat "at the entrance to Resurrection Bay and at Bear Glacier." [59] So far as is known, no further pleasure trips to the park took place again until 1927. Captain Heinie Berger that year began operating his M.S. Discoverer between Seward and nearby points. In order to publicize his service and to create some community good will, Berger announced that for a mere $3, he would take local residents on a daylong scenic tour to Bear Glacier, Chiswell Island [sic], Seal Rocks, and Northwestern Glacier. The day set for the tour was Sunday, June 5. Poor weather, however, descended on Seward that day. The trip was cancelled, and the excursion was never rescheduled. [60]

For the remainder of the 1920s, and on into the 1930s, occasional tourist and hunting parties ventured into park waters. In 1927, for example, Seward police and fire chief Bob Guest headed off on "a sea voyage ... which will take in Seal Rocks and Nuka Bay." Two years later, a large party composed of the Seward Chamber of Commerce and their families cruised down the bay and got as far as Cape Resurrection and Bear Glacier before returning home. That same year, businessman Mel Horner shot a black bear at Bear Glacier, and in 1933 a Seattle physician named Frederick G. Nichols and his son spent almost two months in and around Nuka Bay engaged in fishing, hunting, and prospecting. [61] Nuka Island resident Pete Sather, the well-known Nuka Island resident, was glad to convey several of these parties. It should be noted, however, that Sather himself apparently found little enjoyment in the scenery that surrounded his daily travels. As Kenai Peninsula historian Elsa Pedersen has noted, Sather "did not notice the sure-footed mountain goats or the glossy black bears except as possible quarry for hunting parties he occasionally transported." [62]

|

| The coastal littoral has long attracted a small corps of hunters on the lookout for mountain goats and black bear. Marilyn Warren photo, in Alaska Regional Profiles, Southcentral Region, July 1974, 147. |

In 1925, Seward witnessed a new form of recreational opportunity–aviation–that quickly put the previously inaccessible fjord and icecap country west of town within easy reach. That August, aviators Russell Merrill and Roy J. Davis flew from Anchorage down to Seward, and for the next several days the pair offered rides to all comers. The Alaska Road Commission, reacting to the growing popularity of aviation, roughed out an airfield in 1927-28, and in May 1928, Merrill and Davis "took three local passengers ... for a short flight over the bay and mountains." Aviation quickly caught on with Alaska's trappers, game guides and other outdoorsmen, but few tourists signed on, at least in Seward. [63]

Additional attempts to fly tourists took place during the 1930s, with mixed results. In 1932, Alaskan Airways began offering tourist flights from Seward to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. In all likelihood, few responded to this offer. The following June a new pilot, Art Woodley, began offering a series of flights out of Seward. The news article announcing his flights spared few adjectives in describing the surrounding countryside:

Seward, the Kenai ice cap and the marvelous scenic wonders of Resurrection Bay from the air is the temptation Pilot Arthur Woodley will toss to local residents Sunday when he will be prepared to provide a series of airplane flights beginning early in the afternoon, weather permitting.

The flights will be made in the handsome six-seated, 300-horse power Bellanca plane.... The flights will be divided into two divisions for local air excursions. Ten dollars will be charged for a cruise over the great eternal ice cap of the rugged Kenai Peninsula, from which vantage point the marvels of hundreds of miles of scenic grandeur will be unfolded from Prince William Sound to Cook Inlet.

There will be the lesser flight out over Resurrection Bay, with the broad Pacific laving the rugged shoreline, another treat of thrilling scenic wonders. For this flight a fee of $5 will be charged....

Lastly, there will be the Russian River fishermen's cruise, down where the 30-inch Rainbow trout sport in the crystal pools and challenging the angler. For this cruise a fee of $15 will be charged for the round-trip.

These cruises should have a strong appeal to all who have never beheld Alaska's scenic wonderland from the ethereal heights, from which to look down upon a world shedding its chaste garments of winter for the verdure of spring, its mighty glaciers and Brobdingnagian pinnacles reaching upward to greet the air-minded. [64]

Despite the favorable publicity, Woodley was unable to fly that day, "pea-soup weather" being the culprit. A few days later, however, the weather cleared. [65] His operation that summer evidently had some success, because he offered a similar variety of flights the following year. Three years later, John Littley established Seward Airways, which evidently lasted only a short time; two years later, Seward Airways, Inc. commenced operation. Neither of these carriers appears to have advertised scenic or recreational flights as a primary aspect of their operation. [66]

kefj/hrs/hrs10a.htm

Last Updated: 26-Oct-2002