Changing Times Challenge Native FishIn a quiet cove on Lake Mohave, a few fish group together near the sandy bottom. They don’t have the streamlined shape of striped bass or the recognizable whiskers of catfish. Instead, they look almost prehistoric, with bony humped backs and squared-off snouts. They’re razorback suckers, one of the few species of native fish in Lake Mead and Lake Mohave. Under the careful watch of scientists and conservation workers, they’re making a stand in the face of extinction. Historically, millions of razorbacks thrived along the Colorado River from Wyoming to Mexico1. Back then, the ecosystem was a dynamic waterway that constantly moved sediment and water downstream. But after the construction of the Hoover Dam (and other dams along the Colorado) things changed, and a single, uninterrupted river was broken up into separate reservoirs2. Instead of churning with raging flows every spring, then reducing to a series of slow, still pools every summer, the water flowed more consistently. The dam changed the flowing river into a system where muddy sediment settled to the bottom, with no strong current to keep it churning.

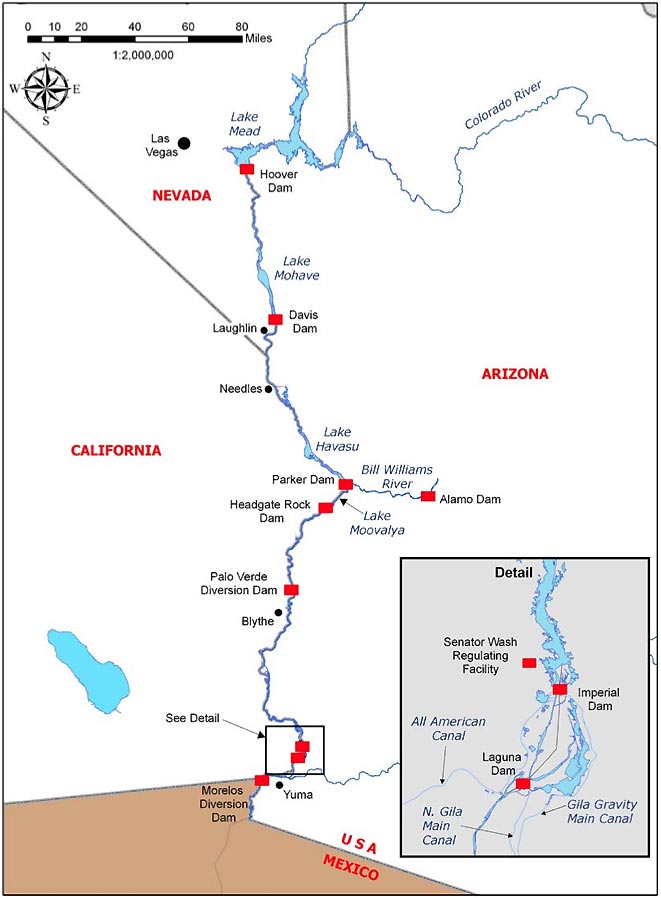

Many dams have been built along the Colorado River, transforming a flowing river into several reservoirs. Big, sudden changes like these can be challenging for species. After nearly a million years in the Colorado River, razorbacks were supremely adapted to this dynamic habitat. But without sediment clouding the water, young razorbacks couldn’t hide from predators like they had done in the past. Fish looking for a mate had a much smaller selection to choose from, since the population was splintered between the lakes. Also, the new, colder water temperatures harmed developing eggs. Other changes spelled trouble too, like the chemicals flowing into the lake from growing human settlements and industries nearby. But the biggest challenge for razorbacks was yet to come. By 1980, more than fifty new fish species had been introduced into the Colorado River Basin. Some arrived by accident, but many were stocked intentionally, including sport fish like bass and trout. These new arrivals turned the native fishes’ habitat into a fiercely competitive zone. Not only did the razorbacks have to compete for food and space, but the sport fish began feeding on native fish, causing populations to plummet even further. By 1991, it was clear that razorbacks were in trouble. While there were still over 40,000 razorbacks in Lake Mohave, they were all older fish that had hatched prior to the creation of Lake Mohave in 1951. These fish were still spawning, but none of the young fish lived to adulthood to reproduce. It was decided that without action, loss of this population within 20 years was likely. Other populations along the Colorado River were in similar situations, so the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the species as endangered, giving razorback suckers special protection through the Endangered Species Act and setting aside critical habitat. Since then, biologists and conservation workers from many agencies, including the Bureau of Reclamation3, National Park Service, Nevada Department of Wildlife, Arizona Game and Fish Department and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have worked together to prevent loss of the razorbacks.

An adult razorback sucker swimming in Lake Mohave. This collaborative work involves collecting newly hatched larval fish4 from the spawning beds, and growing them in hatchery and pond facilities to a size capable of avoiding predation. The program involves not only protecting and monitoring the razorbacks that currently inhabit the waterway, but also breeding these fish in captivity to give the population5 a boost. Scientists are constantly studying water quality, habitat characteristics and fish behavior to develop new ways to help the species thrive. In the 1970s, razorbacks were believed to have disappeared from Lake Mead. A small population of fish was discovered in the 1990s, spawning in one location near Las Vegas Wash. More intensive monitoring since then has discovered6 additional spawning locations scattered around Lake Mead, with an estimated population of 400 adults. This population, however, is unique among razorback populations along the Colorado River for continuing to spawn and survive without any management. Thanks to these efforts, local razorback populations are starting to show signs of improvement. Lake Mohave numbers appear to be stabilizing at sustainable numbers.7 For instance, more than 3000 razorbacks call Lake Mohave home, and captive reared fish are now growing into reproducing adults. The significant genetic diversity in the Lake Mohave population has been retained. The numbers in Lake Mead, while still low, represent a population that has adapted to the changing environment and reproduced several generations. While numbers in Lake Mohave have contained to drop as the last of the older population has died off, recent improvements are significant and illustrate how collaborative and intensive management can help a native fish survive in a changing landscape. Why save a species?

The desert tortoise is one of several threatened and endangered species that call Lake Mead NRA home. Many people love to see wildlife, whether it’s flowers in a nearby field or bighorn sheep clambering over a rocky cliff. But it’s becoming harder and harder for plants and animals to thrive in the wild – the United Nations Environment Programme estimates that as many as 200 species of Earth’s plants and animals disappear every day. Locally, several threatened and endangered species call Lake Mead National Recreation Area home, like the razorback sucker and desert tortoise. While large scale efforts are underway to protect these species, it’s only natural to ask why we should spend money and a great deal of time to protect them at all. Read MoreFish Followers

An NPS employee holds a razorback sucker for research before it is released. Imagine a scientist that needs to find, observe and count a specific species of study animals, but this species is extremely rare, lives underwater and is often on the move. This challenging scenario is the tough reality for the biologists that study razorback suckers in lakes Mead and Mohave. However, when it comes to saving these slippery species, scientists have figured out some clever tricks. |

Last updated: April 7, 2017