The middle and upper portions of the extensive John Day strata can be conveniently divided into four major fossil-bearing units deposited between 30 and 18 million years ago. From oldest to youngest, they include the Bridge Creek Flora, Turtle Cove, Kimberly, and the Haystack Valley.

More fossils are found in the John Day strata than in any other layers in this area. This period continues the general trend of cooling and drying in North America. Early in the John Day time, when the Bridge Creek and Turtle Cove units were formed, the climate was temperate and humid. By the time the later Kimberly and Haystack Valley units were deposited, it was cooler and drier.

Watch for indications of changes in climate and landscape as you proceed on your journey through the units of the John Day strata.

The Bridge Creek assemblage Many layers of fine-grained shales preserve evidence of a large number of lakes in this area. Periodically, these bodies of water filled with sediments from ancient volcanoes to the west. Over time, successive layers buried millions of leaves, and occasionally fish, insects, frogs, and salamanders. The different colors of the rocks containing the Bridge Creek Flora, such as the brightly colored Painted Hills, represent alternating layers of lake-bed sediments and wildly varied paleosols – fossilized soils – which accumulated over millions of years.

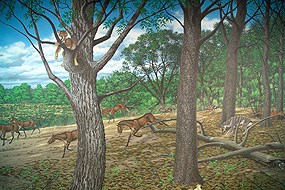

The Turtle Cove assemblage Over millions of years, volcanoes more than a hundred miles to the west spewed out material that became the Turtle Cove rock layers. Welded ash flow tuffs – hard rock formed from flows of superheated gases, ash, and pulverized rock – were left behind. Thick sequences of blue-green claystone formed from redistributed ash. Within each of these colorful layers is an impressive variety of unusual fossils, many unique to the Pacific Northwest. They were entombed in ash-rich sediments that were deposited on a wide variety of environments.

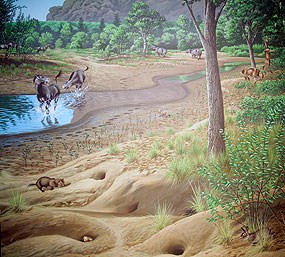

The Kimberly assemblage Above the striking green beds of the Turtle Cove are the buff-to-pink volcanic sediments of the Kimberly. Like the Turtle Cove, much of the strata of the Kimberly represent ancient floodplains with fossil soils and stream channels. These light pink or gray-to-buff layers are very similar in mineral composition to the Turtle Cove beds they typically cover, but do not contain the blue and green minerals, clays, and zeolites that give the Turtle Cove its distinctive color. In many places, the Kimberly consists of thick sections of redistributed volcanic ash with abundant fossils.

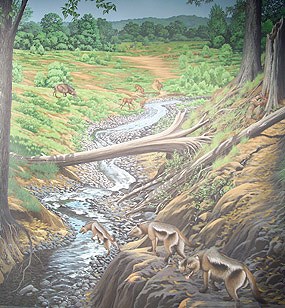

The Haystack Assemblage The Haystack Valley rock layers are a complicated series of sands, gravels, ash-beds, and paleosols. During the Haystack Valley time, low-lying areas were uplifted. As the elevation of the area increased, numerous valleys were carved by streams that cut deeply into underlying Kimberly paleosols. These processes formed sequences of sandstones and conglomerates – pebbles and cobbles cemented together by other minerals – as additional airborne ash from volcanoes settled.

The Haystack Valley assemblages are found in the youngest rocks deposited prior to the flood of basalts. Hardwood forests still dominated the land, but grasses gained headway as the climate continued to cool and dry. The Haystack Valley time period featured cottonwood trees, alders, shrubs, and shallow rivers. These trees and leafy plants supported rhinos and chalicotheres – horse-like creatures with claws. These massive browsing animals were joined by smaller grazers such as camels and horses who were more suited to the developing open grassy ranges. |

Last updated: January 3, 2018