From Appendix I of a Survey of Historic and Prehistoric Resources in the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

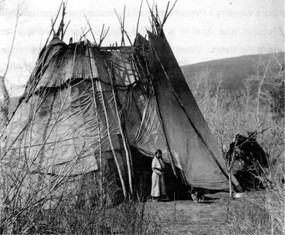

The Northern Paiute were the main Shoshonean speaking culture in Oregon. The Bannock also spent some time in the area which is now Oregon. There is much confusion when studying these groups, especially the Northern Paiute, because many of the early explorers and anthropologists were not clear in their use of terms such as Shoshoni, Bannock, Snake, (Steward 1938:271) and, the less than complimentary term, "digger." Those usually called the Shoshoni were Bannock and other Shoshonean groups to the east. Snake probably refers to the Walpapi, a division of the Northern Paiute (Berreman 1927:47; Swanton 1952:475). Digger was probably a descriptive term applied to [American] Indians of the general area. Northern Paiute When looking at the Northern Paiute one encounters two separate systems of classing them into bands or villages. It is extremely difficult to talk of separate bands or villages since they moved very much and tended not to inhabit permanent sites on the scale the Plateau peoples did. One system used more recently are those names supposedly given groups by the Northern Paiute based on what resource they exploited at a certain time of the year. This system has difficulty because membership was fluid in these bands from season to season, and year to year. Not every area of the Northern Paiute territory was occupied either. Beatrice Blyth (1938:396, 403-404) has mapped these resource exploiting groups. South of the Tenino were the Juniper Deer Eaters (Wadikishitika), on the Upper John Day were the Hunibitika (Hunibui - a root), to the northeast of them were the Elk Eaters (Agaitika), south of them were the Tagu Root Eaters (Tagutika), south of the Hunibui Eaters were the Wada Root Eaters (Wadatika), around Lake Albert and Summer Lake were the Epos Eaters (Yapatika), at Warner Lake were the Groundhog Eaters (Gidutikad), and to the east and south of them were the Gwinidiba (meaning unknown). These names do not represent political units, since they split into smaller family and friendship groups when not exploiting their particular resource. The Northern Paiute groups generally divided up into smaller kin and friendship units. These units consisted of two or three families not necessarily related. Kinship was bilateral since one married and chose residence usually on the basis of what was most feasible (Fowler 1966:59). This was because resources were scarcer in the Great Basin than elsewhere in Eastern Oregon. The people traveled about on foot in these small units most of the time and only came together into larger-groups for short periods where some resource was especially abundant (the band name). Perhaps these groups traveled only in their particular drainage system and there was no appreciable band movement over time, since there was no reason to cross barren wasteland (Davis 1966:151). The family or small group was the basic political unit, and nearly the only social or cultural unit. Their houses were of brush and usually very temporary in design. They commonly ate seeds, roots, insects, and small animals, but they prized game animals and fish, eating them when they were able to obtain them. The Sahaptian speaking people to the north were their traditional enemies; According to Berreman (1937) they raided these people, but it is more likely that the Plateau peoples raided them (Ray 1938). Lohim The existence of a group of Shoshonean speakers on Willow Creek in the middle of a group of Sahaptians, the Umatilla, is questioned. Berreman (1937:61) states that the group in question, the Lohim, were Northern Paiute, while Steward (1938:407) says they were a band of Lemhi, from the Bannock, who arrived from Idaho after 1856. The second theory seems more plausible. The U.S. government never recognized them and some scholars doubt their existence. Bannock The Bannock Indians are also a group of Shoshoneans of which part of them occupied Oregon for a time according to some anthropologists. They hunted large game animals on a larger scale than the Northern Paiute and are generally considered with the [American] Indians of Idaho. Wasco-Wishram and Watlala The speakers of the Chinookan linguistic stock stretched from the mouth of the Columbia River to around the region of Celilo Falls near The Dalles, Oregon. The Upper Chinook lived on most Chinook territory and were the only Chinook east of The Cascades. The Wasco on the Oregon side of the Columbia and the closely related Wishram on the Washington side were the easternmost of the Upper Chinook. They lived east to Celilo Falls and the Five Mile Rapids area. More anthropological study has been done on the Wishram than the Wasco, and much information about the latter is inferred from the former (French 1961:339). Below the Wasco, from Hood River to The Cascades, was the Watlala (Barry 1927:53) or Hood River of which little is written. The Wasco-Wishram were intermediate between the Plateau and Northwest Coast cultural areas. They maintained trading partnerships with both Northwest Coast groups and those of the Plateau. From the Klamath they obtained slaves that were raided from northern California, from the east they received skins and Plains traits, from the west seafood and shells, and they traded with peoples from the north. As middlemen in a vast trade network they were extremely important. Salmon was the staple item of trade and their main food source. Perhaps the most excellent spot on the Columbia River for these anadromous fish was at Celilo Falls in the midst of the Wasco-Wishram. The Wasco-Wishram kept slaves, who were the lowest "caste" in a three or four caste system. One big notch above the slaves were the commoners, and above them were the rich and/or chiefly classes. This class system and the common practice of keeping slaves were typical of the Northwest Coast. Chieftainship was hereditary, being passed from father to son if the son was worthy. The same system held for subchiefs as well as for heads of wealthy families. Duties of the chief were advisory and judicial. They often served as intermediaries in village disputes, as there appears to have been no council. In Eastern Oregon, as for the whole Northwest, there was really no such thing as a tribe in the terms of political networks that stretched beyond the individual villages. Except under extreme conditions a chief was only a leader of a local group, and the culture, or aggregate of villages speaking the same dialect, was held together by cultural and social bonds rather than political bonds. The above was true of the Wasco-Wishram (French 1961:361) who lived in villages each with its own leaders. The winter village was near the river and permanent or semipermanent in nature, with the houses constructed of cedar planks (Curtis 1907:8:91; French 1961:358). In the summer they moved from camp to camp fishing, hunting, berrying, and digging roots. This temporary abandonment of winter villages has led many anthropologists astray, since to the early explorers it appeared that the [American] Indians of the Columbia River had fled from the area (Ray 1938:394). |

Last updated: August 25, 2024