Where Hides and Beads Changed Hands: The Upper Missouri Fur TradeFor hundreds, maybe thousands, of years before Euro-American trappers and traders reached the Upper Missouri River, intertribal trade networks crisscrossed the mountains and prairies and extended from coast to coast. With their arrival, Euro-Americans' capitalized on what flourished already among the Upper Missouri peoples: their social networks and desire for new, different, convenient, and sometimes exotic foods, clothing, crafts, tools, and other commodities. Like their new trading partners, who desired furs and food, the native peoples sought materials and goods they themselves couldn't procure or manufacture.

Like many of us today, the Upper Missouri peoples appreciated fine craftmanship and beautiful goods made from quality materials; they also wanted the best for making their own clothing, jewelry, arrowheads, and tools. Prior to the 1800s, the trade for items such as Knife River flint, dentalium shell, and pipestone (or Catlinite) commonly occurred at formal gatherings or "trade fairs." During these gatherings—they often took place in the area of the Mandan-Hidatsa villages in present-day North Dakota—people renewed family ties and other social bonds. Even after Euro-Americans arrived, these social practices continued; in fact, they proved vital to the fur trade's eventual success.

NPS The Beginnings of BusinessThe first Euro-Americans arrived on the northern plains as early as the 1730s. As independent entrepreneurs, these French-Canadian and -American men traded with their tribal counterparts, and, to secure trade relationships, often married into the tribes. The many tender familial ties and new Métis culture that these marriages created benefited the traders and brought prestige to the wives' families. The women's knowledge of local cultures and languages, most not spoken by their trader-husbands, made wider communication possible, expanding family networks and community obligations as well as business opportunities. International rivalries also influenced the fur trade's formation and practices. After the United States purchased Louisiana from France in 1803, Britain's Hudson's Bay Company and John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company, among others, competed for regional dominance and tribal loyalties. By the 1820s, as part of this process, the opposing companies built trading posts that supplanted the Upper Missouri peoples' trade fairs. First built in 1828 and later enlarged, Fort Union, then the American Fur Company's westernmost post, dominated the Upper Missouri fur trade for decades to come. By the time it closed in 1867, the fort had become the nation's longest-functioning fur trade post. Where Trade and Culture ConvergedAs an outpost in a global venture, the fur trade, Fort Union functioned as a place of convergence and commercial as well as cultural exchange. In trade for beaver pelts, brain-tanned bison robes, and other furs sold nine months to a year later to urban American and European consumers, the Upper Missouri peoples received firearms, textiles, foodstuffs, and innumerable manufactured goods. The American Fur Company and Fort Union's successive owners, the Upper Missouri Outfit and Northwest Fur Company, imported these trade goods from countries around the world, including France, England, Belgium, and China. Among the most popular of trade items were colorful glass beads imported from Italy and Austria. The post's traders often gave these beads and shoulder arms such as the North West rifle as gifts to Assiniboine and other tribal leaders who brought in for trade hides of the highest quality.

NPS Not all trade goods brought to Fort Union by horse-drawn wagon or steamboat were finished products. Fur traders in some cases discovered it was easier and less costly to ship to the post raw materials such as sheets of tin instead of finished manufactured goods. This is one reason why so many craftsman—tin- and blacksmiths, carpenters—lived and worked at the post either seasonally or year-round. While tinsmiths, for instance, made cups and plates, blacksmiths forged items such as chains for animal traps and iron arrowheads.

The Transformation of Everyday LifeJust as new technologies today transform our everyday lives, the introduction of manufactured goods and international products altered the Upper Missouri peoples ways of life and standard of living. Metal projectile points and firearms made hunting easier, meaning individuals and tribes could hunt more game from which to supply traders with pelts and robes. Personal adornment also changed. In addition to the porcupine quills and shells they traditionally used, native peoples increasingly acquired "trinkets"—tinklers and bells, for instance—made with imported metal. Beads, meanwhile, replaced porcupine quills. Not all imports improved the Upper Missouri peoples' lives, however. European diseases such as smallpox decimated local populations. As a result, the balance of power within and between tribes shifted, making possible the Lakota peoples' eventual rise to regional dominance. Alcohol traded illegally at Fort Union and opposition posts also proved to be a disruptive and destabilizing influence.

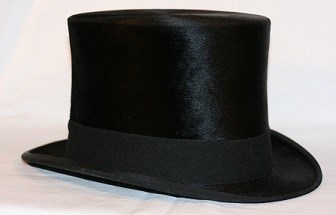

NPS The Assiniboine and other tribes, meanwhile, boasted that whites labored to serve their needs. From the fur traders' perspective, however, the Upper Missouri peoples were the suppliers and consumers whose desires created opportunities for realizing handsome profits, at times as much as $100,000 a year. As the Assiniboine and neighboring tribes annually traded pelts and robes at Fort Union, shipments sent downriver to St. Louis earlier were sold at auction for manufacture into clothing sold eventually on the domestic and foreign markets, where consumers valued the hides for their warmth and as symbols of wealth. Members of the American and European upper classes, for instance, wore stylish and waterproof beaver-pelt hats. Buffalo robes, meanwhile, served as warm winter bedspreads, coats, or lap covers during chilly sleigh rides. Today, the fur trade has ceased to be a major economic activity on the Upper Missouri River. Nonetheless, the global trade it once was a part of has continued and accelerated. A significant percentage of the food, clothing, and appliances the region's present-day residents rely on for survival and enjoyment originates far from their homes, in Asia and South America. The northern plains concurrently export crude oil, wheat, corn, and agricultural technologies and equipment to countries around the world, including those with historic trade ties to Fort Union and the confluence country, among them, Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and China. It is these and other local and global connections that Fort Union's visitors continue to discover and experience as they follow in the wakes and footsteps of their ancestors and countryman, citizens of the world. American Indians and the Fur TradeAt least seven Upper Missouri tribes came to Fort Union to trade, with the primary trading partner being the Assiniboine. The stories of these and the region's other native peoples date back to their long-ago origins. Although these mostly oral histories are ones that can't be told in an hour or a day, they're ones that can be heard and learned over time. In the meantime, artifactual evidence of these peoples' origins, beliefs, cultures, and ways of life can be seen in Fort Union's museum collections and at nearby places such as Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site and Writing Rock State Historic Site. River TransportationFor fur traders, the Missouri River was a principal route of travel. Keelboats were a major mode of river travel until 1832, when the first steamboat, the Yellow Stone, docked at Fort Union. Mackinaw boats were another mode of river transportation made and used by the post's worker's, while the region's tribes constructed circular bull boats from green willow branches and a single bison bull's hide. |

Last updated: April 24, 2021