It's Not Where You Thought it Was: Fort Union, the Fur Trade, and the Birth of the National Park Idea

NPS / EMILY SUNBLADE Today, America’s national parks are icons recognized the world over; they’re among the nation’s most esteemed institutions, acknowledged by an overwhelming majority of citizens as one of the country’s greatest resources. But it wasn’t always so. Yellowstone, the first national park, wasn’t established until 1872, the National Park Service itself not until 1916. Decades before, as unlikely as it seems, the idea for “a nation’s Park” started here in the northern plains, in big sky country with its wide-open, oceanic prairies and herds of bison as seemingly numerous as then in-flight flocks of earth-darkening passenger pigeons. This land where Fort Union stands near the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers’ confluence unsettled and challenged people’s preconceptions; a landscape alive with rushing waters and peoples and a plethora of plants and animals—the very things Euro-Americans’ arrival eventually threatened—became the place where artists and scientists, fearing loss of the nation’s native peoples and bison, first appealed for a nation’s parks, for conservation.

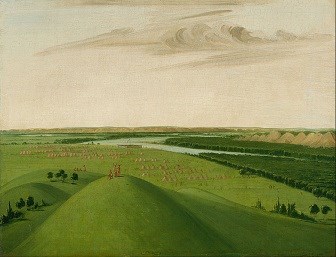

Photograph by the Google Art Project; image provided courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The original is in the collections at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. The Challenged MythIt was the summer of 1832. A young artist sought to document the West and its Native American residents and their ways of life. It's true this Philadelphian's beliefs were steeped in the mythoi of his day and upbringing. He believed, for instance, in the romantic notion of the "Noble Savage," whom he sought to see and record in journals and paintings kept and made as he steamboated West up the Missouri River to Fort Union and canoed back to St. Louis. During his weeks at Fort Union and locations farther east along the Missouri River, George Catlin met, sketched, and painted portraits of the men, women, and children from the Upper Missouri Tribes—the Assiniboine, Blackfeet, Crow, Cree, Mandan; he also observed and participated in buffalo hunts. His journey continued the witness and engagement that Meriwether Lewis and William Clark themselves had continued in 1804–1806, following as they had in the footsteps and wakes of the region's native residents and earlier Euro-American fur traders. Unlike Lewis and Clark, however, Catlin feared for the loss of the native peoples and their way of life, its innocence and purity: "Nature has no where [sic] presented more beautiful and lovely scenes, than those of the vast prairies of the West;" Catlin penned in his letters published in 1841, "and of man and beast, no nobler specimens than those who inhabit them—the Indian and the buffalo—joint and original tenants of the soil, and fugitives together from the approach of civilized man; they have fled to the great plains of the West, and there, under an equal doom, they have taken up their last abode." These people and the bison they relied on deserved "preservation and protection" "in all the wild and freshness of their nature's beauty." To ensure this, Catlin proposed creation of a "nation's Park" "by some great protecting policy of government."

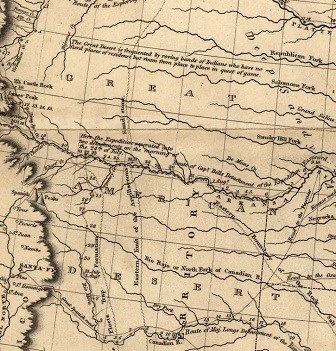

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS More important in hindsight than Catlin's proposal, first though it was, was the effect of the artwork, letters, journals, and books he and later artists and scientists produced after visiting Fort Union. Because of the Upper Missouri fur trade, the ethnologist John C. Ewers claims, "no other section of the trans-Mississippi West was portrayed so extensively and so vividly by artists during the days before the development of photography." Landscapes drawn and painted by Catlin; Karl Bodmer, a Swiss artist who visited the post in 1833; and John James Audubon and his illustrator Isaac Sprague, who spent two months at Fort Union in the summer of 1843, all contributed to viewers in the eastern United States, Europe, and elsewhere seeing and eventually accepting the American West, then the Great Plains, as something more than the great desert it had been called by the likes of Lewis and Clark, Zebulon Pike, and, most famously, Stephen H. Long. Long's 1823 expedition report had featured a map on which the plains were labeled the "Great American Desert." "It has been, heretofore, very erroneously represented to the world," Catlin would write, "that the scenery on this river [the Missouri] was monotonous, and wanting in picturesque beauty. This intelligence is surely incorrect," he proclaimed, "and that because it has been brought perhaps, by men who are not the best judges in the world of Nature's beautiful works." Long's report may, ironically, have attracted fur traders to the West. Their arrival led to Fort Union's 1828 founding and the appearance at the confluence of artists and scientists, including the geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden, where they observed, witnessed, documented, and reported on a land unlike the barren and sterile wasteland, or desert, they'd been prepared to expect. This gradual transformation in peoples' understanding of the land, in combination with technological advances in agriculture and transportation and the discovery of gold in Montana, drew ever-increasing numbers of Euro-Americans into the West. The Killing FearThe transformation in people's expectations and attitudes toward place may not have been the fur trade or Fort Union's most significant contribution to later American history. The introduction of smallpox to the northern plains peoples in 1837 and 1838 would likely rank higher; this and other disease outbreaks killed thousands upon thousands, nearly wiping out entire tribes, and in the process shifted the balance and dynamic of power on the plains. It made possible the later dispossession of lands from the Upper Missouri Tribes. With fewer people, those who survived may have become more dependent for survival on the fur trade and places like Fort Union. But even before this, as Catlin so powerfully expressed, some began to fear for the land and peoples' future. That artists and scientists' created new ways to see and imagine the land, one effect of Fort Union and the fur trade, only exacerbated the pressures they felt with the pioneers' and miners' arrivals. What the artists and scientists witnessed and documented also kindled and, like a blacksmith's forge, fanned the flames of fear. But not only, ironically, fear of the people, of the native peoples; as Catlin had, they expressed a fear of the effects of civilization. They expressed a fear of the losses to come.

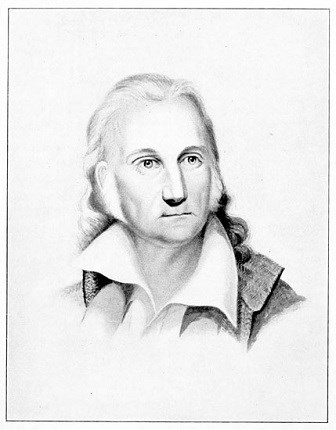

COURTESY PROJECT GUTENBERG Catlin's 1832 call to action (not published until 1841) proved less influential on white Americans' thinking than the observations of a later Fort Union visitor and his travel companions: the naturalist and artist John James Audubon, Edward Harris, Isaac Sprague, and John G. Bell. After leaving the West, Catlin had spent the better part of 30 years promoting his artwork and ideas in Europe. Audubon and party, by contrast, remained in America after their 1843 journey. Back East, they capitalized on and built additional social capital among people of influence. Audubon himself, of course, was already famous for publishing Birds of America, the most definitive work of ornithology yet produced in the United States. In June of 1843, however, he'd come to Fort Union to create a similar work to document the country's viviparous quadrupeds, its four-legged animals that bear live young. Accompanying Audubon were his illustrator, Sprague, a young artist whose only known formal training occurred under the direction of Audubon on this Fort Union trip. Sprague sketched and illustrated the plants and backgrounds in many of Audubon's prints featured in Birds of America's final volume and in the 1851 quadruped books. Their work together, like Catlin's, exposed this rich Missouri River landscape to Americans who'd thought of it before only in terms synonymous to a Biblical desert. Afterward, Sprague became America's most skilled and sought-after botanical illustrator, his sketches filling the pages of works by the likes of Asa Gray and John Torrey; in the process, though little known today, as his biographer Emanuel Rudolph writes, Sprague became a major contributor to the "professionalization of nineteenth-century American science."

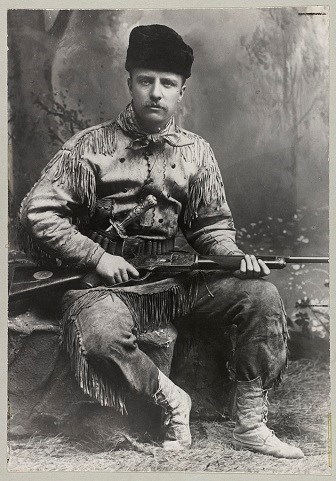

© R&L HONEYMAN As deadly as nineteenth-century scientific practices were for animals (the untold numbers of specimens killed for measurement and illustration), they led scientists and hunters, observers of the natural world, to witness first-hand the losses Catlin had feared in 1832. Audubon, like Catlin, not only participated in and observed Fort Union's daily life and activities—the routine comings and goings of Assiniboine and other tribes, trade negotiations, and nightly entertainment like fishing for wolves—he also traveled throughout the confluence area and participated in buffalo hunts. He witnessed hunters' indiscriminate killing of bison, including by members of his own party; more often than not, they'd take nothing more than a bison's tongue, the rest of the bull or cow left for wolves or to rot. "Provost [one of Fort Union's hunters] tells me that Buffaloes become so very poor during hard winters," Audubon writes in his journal for August 5, "when the snows cover the ground to the depth of two or three feet, that they lose their hair, become covered with scabs, on which the Magpies feed, and the poor beasts die by hundreds. One can hardly conceive how it happens, notwithstanding these many deaths and the immense numbers that are murdered almost daily on these boundless wastes called prairies, besides the hosts that are drowned in the freshets, and the hundreds of young calves who die in early spring, so many are yet to be found. Daily we see so many that we hardly notice them more than the cattle in our pastures about our homes. But this cannot last; even now there is a perceptible difference in the size of the herds, and before many years the Buffalo, like the Great Auk, will have disappeared; surely this should not be permitted." Three days later, writes Audubon, post hunters were "despatched [sic] with a cart to kill three fat cows but no more; so my remonstrances about useless slaughter have not been wholly unheeded." The Direct ConnectionThe effect on Fort Union's hunters of Audubon's concern for the bison, evidence of an emerging conservation ethic developed during a long career and extensive travels, was no doubt negligible and short-lived. Audubon and party departed Fort Union on August 16. But much like the waves produced when a raindrop hits a pond's surface, the sentiment no doubt spread, reaching far and wide and even into the future as he and his companions shared it once they returned to the East. In fact, although born before Fort Union's 1867 demise, a man who later became world famous as a conservationist only because he came to North Dakota never walked the post's palisade-enclosed grounds. Nor did he ever talk with Audubon, a childhood hero. That man, Theodore Roosevelt, nonetheless knew of Fort Union; he knew, too, of the work produced by the people who'd visited that Upper Missouri fur trade post. Most important of all, however, as a boy in New York he learned directly from the 31-year-old man who'd hunted and stuffed the bird and quadruped specimens that Audubon and Sprague had collected and sketched at Fort Union. John G. Bell, Audubon's taxidermist, returned to New York, where on Broadway in New York City into the 1870s he operated a taxidermy shop. It was there in that shop in 1871 and 1872 that a future president and admirer of Audubon, a childhood aspirant to a career in natural history, learned from Bell. "He was tall, straight as an Indian, with white hair and smooth-shaven clear-cut face," Roosevelt would write in 1918; "a dignified figure, always in a black frock coat. He had no scientific knowledge of birds or mammals; his interest lay merely in collecting and preparing them." From the man Audubon credited with recognizing the Western Meadowlark as a new species, Roosevelt, then thirteen or fourteen, learned "as much as my limitations would allow of the art of preparing specimens for scientific use and of mounting them." At least one Roosevelt biographer has claimed that Bell's stories of his expedition with Audubon "fired the imagination of his young student. Bell's instruction, wrote Roosevelt, 'spurred and directed my interest in collecting specimens for mounting and preservation.'"

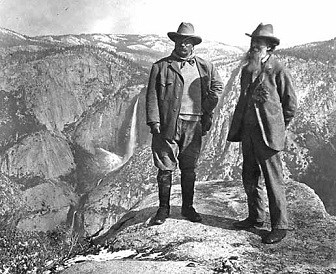

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Roosevelt EffectThe truth of Bell's influence on a young and impressionable future president may never be known, just as what happened within Fort Union's white-washed palisade walls and bastions—the conversations, for instance, that occurred in its courtyard and clerk's office or on its hearth stones in the trade room—may never be known. But they can be imagined. Was it in part because of his childhood memories of Bell's stories that Roosevelt chose to travel to North Dakota in 1883? That he chose North Dakota as a sanctuary following his wife's and mother's deaths on the same day? What else may never be known is what more than a taxidermist's skills Roosevelt learned from Bell. The taxidermist died in 1889, while Roosevelt was still a young man, and the records he left appear to be few, the thus far known references to him by Roosevelt equally few. What we know for certain, of course, is that Roosevelt came to North Dakota and afterward, because of his experiences, co-founded the Boone and Crocket Club with another Audubon admirer, George Bird Grinnell. Under their leadership, that organization led the nation in advocating for conservation and the protection of Yellowstone National Park's few remaining bison, then one of only two surviving wild herds. Later still, as president, Roosevelt led the nation in adopting and enacting conservation legislation and in preserving places known today around the world as America's pride and joy, its national parks.

NPS Roosevelt himself didn't directly create the National Park Service (NPS). He did, however, encourage and fight to create the social, political, and cultural climate in which the NPS was founded in 1916. He helped to establish the climate that not only nurtured the NPS but also, through its first directors, Stephen Tyng Mather and Horace Albright, the state parks movement. He also, as president, created the national wildlife refuge system. These movements together, influenced by Roosevelt who was influenced by Audubon and Bell who in turn were influenced by their Fort Union experiences, have culminated in the worldwide wave-like spread of the national park idea and creation to date of more than 2,000 sites around the globe that are the equivalent to America's national parks, the idea Catlin first proposed in 1832 while visiting Fort Union and the Upper Missouri River country. It's a country today threatened with resource destruction on a scale inconceivable in either Audubon's or Roosevelt's day, a desecration as much an affront to America's national character and identity as peoples' burning of the Stars and Stripes. What's at stake isn't only beautiful and significant places, places symbolic of the nation's natural and cultural heritage, but what it means to be American not simply here today but everywhere tomorrow. For Americans to continue to protect and preserve places like Fort Union for themselves and all humanity is a sign of wisdom and authority, as vital as Theodore Roosevelt in his day speaking softly and carrying a big stick. |

Last updated: April 23, 2021