Library of Congress People, Places, & Stories

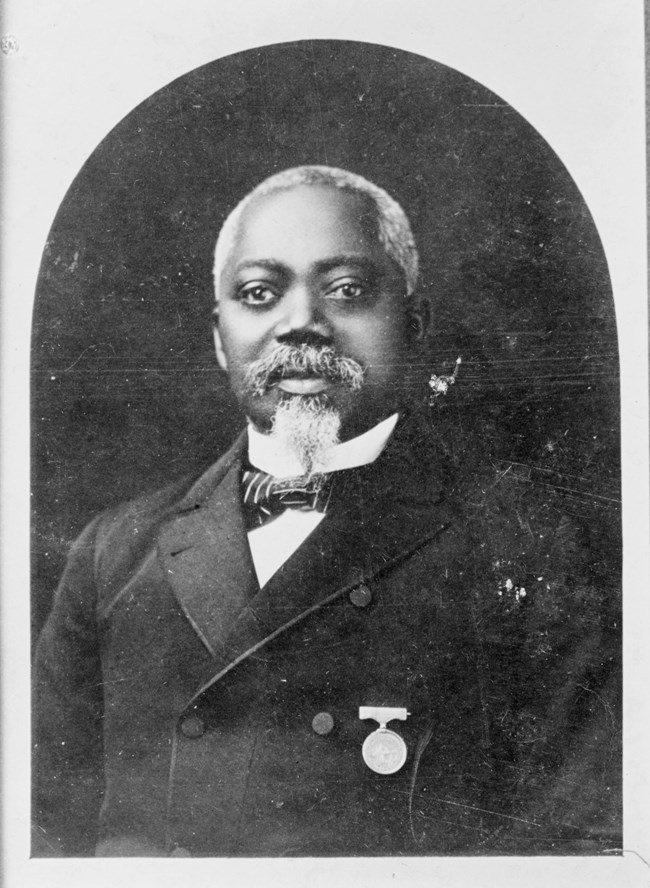

Library of Congress From Freedom Seeker to Medal of Honor Recipient: Sergeant William Harvey CarneyThe Medal of Honor is America’s highest and most prestigious medal for valor in combat that can be awarded to members of the armed forces. The medal was first authorized in 1861 for sailors and marines, and the following year for soldiers. The medal is normally awarded by the President in the name of Congress at a White House ceremony. According to the US Dept. of Defense website, over 3,490 Medals of Honor have been awarded to service members, only one has been awarded to a female service member. Sgt. William Harvey Carney, 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, was an early recipient of the medal and the first African American to receive the honor. (more later on that point) Carney was born into slavery in Norfolk, Virginia in February 1840. At the age of 14, he learned to read and write by attending a secret school sponsored by a local minister. Both Carney and his father sought their Freedom and self- emancipated via the Underground Railroad network arriving in the whaling post of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Initially, Sgt. Carney wanted to be a minister however, after the American Civil War started he heeded the “Call” of the Union Army. In the November 6, 1863, edition of The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper Carney stated “ Previous to the formation of colored troops, I had a strong inclination to prepare myself for the ministry; I felt I could best serve my God serving my country and my oppressed brothers. “ Enlisting on February 17, 1863, Carney joined the newly formed 54th MA Infantry. His regiment was the first African American military unit organized in the northern states. Newspaper advertisements and recruiting posters encouraging men of African descent to enlist, drew volunteers from far and near. One-fourth of the regiment’s volunteers came from slave holding states, others from the Caribbean and Canada. Famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ sons Charles and Lewis traveled from Washington, DC to Boston in-order to join the 54th Massachusetts. By May 14, 1863, 1,000 men had volunteered for the regiment. On May 28, 1863, the regiment departed Boston, Massachusetts on the DeMolay steamer for the coast of South Carolina under the leadership of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. The 54th regiment saw its first military combat on July 16, 1863 in a skirmish on James Island, South Carolina. On July 18, 1863, after several days without sleep, food or water the 54th regiment was directed to lead the attack on Fort Wagner. Adequate reconnaissance had not been conducted and the 54th MA was unaware that 1,800 Confederate soldiers were awaiting inside. The 54th regiment had only 624 soldiers. At 7:45pm, Colonel Shaw raised his sword as he stood by the Stars and Stripes color barrier and lead the charge of his men down the beach toward Fort Wagner. After shouting “Forward 54th!“ Col Shaw received three fatal wounds. Sergeant William Carney was in the midst of fighting when he noticed the soldier bearing the American flag stumble and fall, he too had been mortally wounded. Carney threw away his musket, raised the flag keeping it from touching the ground and struggled up the parapet, though now wounded in the legs, chest, and arm. Carney was able to plant the flag at the top of the foot wall. Despite his wounds and the gunfire around him, Carney was able to keep the flag aloft. Carney and the rest of the 54th Massachusetts were pinned down. Only after reinforcements arrived was the decimated unit able to withdraw. Struggling back to the Union lines Carney collapsed saying “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground.” “During the American Civil War, the job of color bearer was one of the most hazardous as well as important duties in the Army. Soldiers looked to the flag for direction and inspiration in battle and the bearer was usually out in front, drawing heavy enemy fire while holding the flag high.” After the battle Carney was discharged from the military on June 30, 1864, due to his wounds. Several months later Sgt. Carney on a cane due to the injuries to his right leg, posed for a picture (depicted here) holding the very flag he had risked his life for that day at Fort Wagner. Carney returned home to New Bedford, Massachusetts becoming the city’s first African American postal employee and a public speaker, often times speaking at events for veterans. In 1865, he married Susannah Williams, a local school teacher who was one of Massachusetts first African American public school teachers. They had one daughter, Clara Heronia. On May 31, 1897, Sgt. Carney received a standing ovation while attending the unveiling ceremony for the monument to Col Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th MA. Carney led 75 veterans of the regiment into the event carrying the flag used in the attack at Fort Wagner in 1863. The monument was sculpted by Augusts Saint Gaudens and is featured in the film’’ Glory.’’ The principal speakers for the dedication ceremony were Booker T. Washington, President of Tuskegee University and Charles W. Eliot, President of Harvard University. Though Sgt. Carney was the first African American to have conducted an act deemed worthy of the Medal of Honor during the American Civil War, he did NOT receive his medal until May 9, 1900, a gap of 37 years. Robert Blake, a Contraband Union Navy sailor, actually received his Medal of Honor medal first. Blake received his medal in 1864, a mere four months December 25, 1863 heroic actions. Sgt. Carney retains the title of the first African American recipient due to his military combat actions occurring first. While Dr. W.E.B. Dubois and Sgt. Major Christian Abraham Fleetwood, a Civil War veteran and Medal of Honor recipient were preparing an exhibition for the 1900 Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair held in Paris, France, it was discovered that Sgt. Carney had not received his Medal of Honor medal. Fleetwood believing Carney had already been awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Fort Wagner, asked if he could borrow Carney’s medal to display it along with his own medal in the [Negro] exhibition section of the American exhibition. The [Negro] Exhibition section was designed to show the economic and social progress of African Americans since emancipation. Carl J. Cruz, a descendant of Carney, states it was Sgt. Major Fleetwood, 4th USCT who actually completed the required paperwork needed for Carney to receive his Medal of Honor. Over the years Carney’s story inspired song, sculpture, prints, and paintings. In 1901, Carney’s actions inspired a patriotic song written by James Weldon and Rosamond Johnson, “Boy the Old Flag Never Touched the Ground.’’ The Johnson brothers also wrote and arranged the popular “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” The Carney tribute song was featured, in the Broadway musical “Shoo Fly Regiment,” the musical opened June 3, 1907. Upon Carney’s death in 1908, the Massachusetts governor ordered the flag at the state house flown at half-mast. This was an unprecedented act of honor formerly reserved for presidents, governors, and members of Congress. He is buried at Oak Grove Cemetery in New Bedford, Massachusetts. In 1920, Norfolk, Virginia, the city of Carney’s birth authorized a statue honoring Sgt. Carney and other soldiers of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) to be placed in Section 20 of West Point Cemetery.

Library of Congress. Araminta Ross, Known to Most as Harriet Ross TubmanFreedom seeker, military commander, cook, nurse, railroad conductor, scout, and spy all are words which describe the various roles Harriet Ross Tubman played during the American Civil War.Harriet Tubman was born Araminta Ross in 1822 in Dorchester County, Maryland, to Ben Ross and Harriet Greene. One of nine children, Tubman was nicknamed “Minty” by her Mother. Over the years Tubman endured harsh plantation living, including seeing several of her sisters sold, never to see them again. Enslavers often viewed the hiring out of the enslaved persons, even children, as an attractive alternative to selling them. Tubman was subjected to this process and was removed from her family members. Harkless Bowley, Harriet Tubman’s great nephew, recalled in a 1939 interview that Tubman told him that she was “shamefully beaten by a person who “rented her”. She showed me a knot in her side from being struck by one cruel man with a rope with a knot in one end for some trivial offence. The woman [wife of the renter] attempted to whip her, but Harriet would not submit to her. Later when [the woman’s husband] returned home and was informed of Harriet’s actions he beat her. He broke her ribs and may have lacerated her internal organs and Harriet could no longer work. Half- starved and unable to work, Tubman was returned to Edward Broadess, her original enslaver.” In approximately 1844, she married John Tubman, a local free man. It was at this moment Tubman changed her name to Harriet, possibly in honor of her Mother. In October 1849, at the age of 27 years old, Tubman successfully self- emancipated by fleeing to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She left behind her husband who was unwilling to leave the area. Once she arrived in Philadelphia, Tubman became very active in the abolitionist movement. Over the years, Tubman utilized the Underground Railroad network, returning to the South approximately 13 times to lead enslaved family members and others to freedom in the North. Tubman usually worked during the winter months and departed with freedom seekers on Saturday nights, because enslavers would not be able to publish runaway notices in newspapers until Monday. In May 1862, Tubman traveled to Port Royal, South Carolina, where she served as a nurse, treating wounded soldiers and” Contrabands” using home remedies she developed. “Contraband” was a military term commonly used in the American Civil War to describe a new status for certain escaped enslaved persons or those who affiliated with Union forces. Tubman also assisted Major General David Hunter, US Commander of the South Carolina Sea Islands, with recruiting men of African descent for a newly formed military regiment. On the night of June 2, 1863, Harriet Tubman made US military history by becoming the first woman commander of a military operation. With knowledge she had obtained through her work as a scout throughout the South, Tubman led members of the Second South Carolina Volunteer Infantry on a raid. The raid by Union soldiers of the Combahee River area plantations In Port Royal, South Carolina freed more than 750 enslaved persons In the spring of 1865, while traveling in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Tubman encountered a group of nurses who worked for the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC). The USSC was a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to aide sick and wounded Union soldiers. The agency was comprised of thousands of volunteers who raised nearly $25 million to support the cause. The organization was similar to the American Red Cross of today. A USSC agency representative persuaded Tubman to travel with them to Virginia in order to work in some of the Union hospitals along the James River. There was a great need to find someone willing to work at the segregated military hospital at Fort Monroe in Hampton Roads. Tubman agreed to serve and was placed at Fort Monroe’s Colored Hospital to treat wounded and sick African American soldiers and “Contrabands.” However, after observing the inferior medical care being provided by doctors to African Americans soldiers and the lack of adequate medical supplies, Tubman left Fort Monroe in July of 1865 after only serving several months. Tubman had the unique experience of being both in Charleston, South Carolina when the war started at Fort Sumter and of being in Virginia when the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia surrendered at Appomattox Court House. After the war ended, Tubman returned to Auburn, New York, where she opened a home for the aged and infirmed. The home became a National Historic Landmark in 1975. Tubman later became an advocate for Women's Suffrage, even joining the National Woman Suffrage Association. She was also a philanthropist who raised funds to help support new schools in the South and gathered clothing that was shipped to assist the” Contrabands." In 1859, Tubman purchased a home for $1,200 from William Henry Seward, then a US States Senator from New York and a strong abolitionist. Property ownership by women was uncommon in this period of time. In 1869 Tubman married Nelson Davis, an American Civil War veteran over twenty years younger. In 1874, Tubman and Nelson adopted a daughter, Gertie. Though Tubman provided three years of service to the military, she received a total of $200.00 in payment for her service. In 1865, Tubman made her first appeal for military back pay due to her. She claimed the government owed her $966 for her service as a scout from May 25, 1862 to January 31, 1865. That would have been $30. a month for 32.5 months. However scouts and spies were paid $60 a month and army soldiers $15 a month. Even though Tubman was giving the government a discount regarding her back pay, she did not receive payment. Tubman waged a more than 30 year battle to receive her military pension. Congress passed the Dependent Pension Act of 1890, legislation which authorized more general support for veterans and their widows. This action would now allow Tubman to receive a pension. However, it took until October 1895 for Tubman to be granted a widow’s pension of $8.00 a month. She was awarded the pension for the service of her second husband, Nelson Davis. Davis served with Company G, Eighth US Colored Infantry (USCI) during the American Civil War. Harriet Tubman died on March 10, 1913 and was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York. For a woman who played a vital role in US History, it was fitting that she died during the month of March, the month now designated as Women’s History Month. During World War II, The US Maritime Commission named its first Liberty ship the SS Harriet Tubman. The National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), an influential women’s civic organization headed by Dr. Mary McCleod Bethune, had requested that a ship be named in Tubman’s honor. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt launched the SS Harriet Tubman on June 3, 1944, at the New England Shipbuilding Company in South Portland, Maine. The NCNW used the ship’s launching to launch their own US War Bonds Campaign. The NCNW sold $2 million worth of bonds, the cost of the SS Harriet Tubman. On October 29, 2003, US Congress finally passed legislation granting Harriet Tubman her military pension for service rendered during the American Civil War. A payment of $11,750 was allocated to help preserve the historic Harriet Tubman Home located in Auburn, New York. In 2016, the US Treasury Department announced that abolitionist Harriet Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson as the portrait on the redesigned $20 bill slated to be released in 2030. Two National Park Service sites now interpret the life of Harriet Ross Tubman Davis, the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park in Auburn, New York, and the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historic Park in Church Creek, Maryland. Additional information and artifacts of Harriet Ross Tubman Davis can found in the newly opened Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

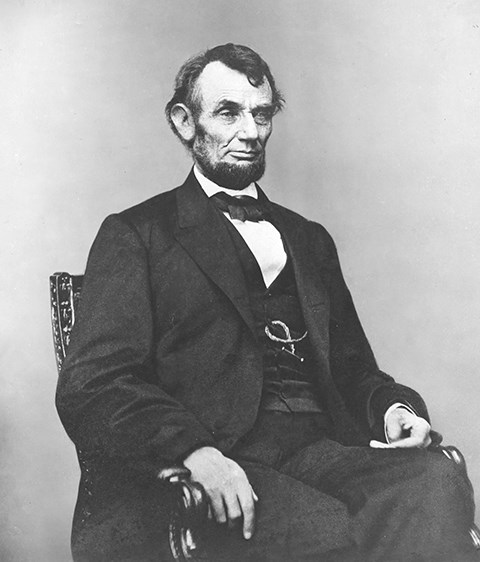

Library of Congress. Presidential Visits to Fort MonroeMany Presidents of the United States have visited Fort Monroe over the years since construction on the fort began in 1819, either before, during, or after their time in office. Andrew JacksonPresident Andrew Jackson frequently visited Fort Monroe and Fort Calhoun, later renamed Fort Wool, during the summers of his presidency, in 1829, 1831, 1833, and 1834. Both forts were under construction at the time. Broken-hearted after the death of his wife, President Jackson spent a lot of time at Fort Calhoun. According to historian Mike Cobb, he made it his “White House.” John TylerPresident John Tyler took sanctuary on nearby Fort Calhoun, later renamed Fort Wool, after the death of his first wife in 1842. He returned in 1844 for a month long honeymoon. He and his new wife Julia Gardiner also spent their first anniversary at the Hygeia Hotel on Old Point Comfort. Millard FillmorePresident Millard Fillmore visited on June 21, 1851. Abraham LincolnPresident Abraham Lincoln stayed as a guest in Quarters No. 1 during his visit May 6-11, 1862. During his visit, President Lincoln, Major General John E. Wool, and Commodore Louis M. Goldsborough planned the attack on Norfolk, Virginia. On February 3, 1865, President Lincoln returned to Old Point Comfort for a peace conference with Secretary of State William Seward, Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens, Confederate Senator Robert Hunter, and Confederate Assistant Secretary of State John Campbell. They met on a riverboat. It was known as the Hampton Roads Peace Conference, and did not result in ending the war, but it helped shape the nature of the later surrender and reconstruction. Ulysses S. GrantFuture president Ulysses S. Grant ended a three-day military conference on April 3, 1864 at Old Point Comfort. Rutherford B. HayesPresident Rutherford B. Hayes delivered a speech at a Naval Review at Fort Monroe, July 4, 1879. James A. GarfieldPresident James A. Garfield met with Brigadier General George W. Getty at Fort Monroe on June 5, 1881 before traveling to the Soldiers' Home in Hampton, VA. Theodore RooseveltPresident Theodore Roosevelt visited Fort Monroe several times before and during his presidency. He visited in 1897, 1906, 1907, and 1909. His visit to Hampton Roads in 1906 included a Memorial Day speech in Portsmouth, VA to Union and Confederate veterans of the American Civil War, which he delivered to a crowd of 50,000 (estimated by the Richmond Times-Dispatch).

On this visit, Roosevelt also privately addressed African American and American Indian students at what was then Hampton Institute. William Howard TaftPresident William Howard Taft visited Fort Monroe on November 19, 1909, at the end of his cruise to Panama to inspect the dam and locks. He returned on June 3, 1912, when the US Navy met the arrival of the German Moltke-class battle cruiser SMS Moltke on its visit to the United States. Woodrow WilsonFrequently overworking himself, President Woodrow Wilson was prescribed forced rest and relaxation by a physician. Golf was President Wilson’s pastime and tonic, and the Hampton Club was located close to Old Point Comfort’s Hygeia Hotel and Chamberlin Hotels, leading health resorts of the day. May 16, 1915, was his first visit to the Hampton Club. It is believed he returned the next year and at other times, but was able to do so without fanfare. When he was in the area, he often visited the Chapel of the Centurion. On February 12, 1916, President Wilson visited Fort Monroe with his new bride, Edith Bolling Wilson, and they were permitted to tour the grounds without an escort. Herbert HooverPresident Herbert Hoover delivered a radio address on October 18, 1931, from the Commandant’s House at Fort Monroe. He spoke on the topic of unemployment relief and began a six-week campaign to raise local relief funds. Franklin D. RooseveltPresident Franklin D. Roosevelt visited Fort Monroe on July 29, 1940, while touring military installations. He arrived at the wharf next to the Chamberlin Hotel and then observed a firing demonstration at Wilson Park. Dwight D. EisenhowerBefore entering politics and being elected president Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wife Mamie Eisenhower attended the wedding of their son, Capt. John Eisenhower to Barbara Jean Thompson, at the Chapel of the Centurion on June 10, 1947. Harry S TrumanFormer President Harry S Truman made frequent to his cousin Gen. Louis W. Truman from 1960 to 1962. There are many tales of “Uncle Harry” visiting Fort Monroe, often incognito. Residents on post were occasionally startled when he appeared unannounced during his famous early morning walks. He also attended at least one meeting of the Masonic Lodge housed in Casemate 20.

Women at Fort Monroe: Before the American Civil WarPeople often associate military history primarily with men, but women have always played a vital role as well, even when officially prohibited from serving in the armed forces. The history of women at Fort Monroe goes back to before the construction of the current fort, but unfortunately this history is often buried more deeply than the stories of the men who served here such as Robert E. Lee and Edgar Allan Poe. Women of Fort Monroe: Army Women in World War IIWomen have played an important role in the history of Fort Monroe over the years, but World War II was especially important as it was the first time in US Army history that women were officially allowed to serve in the Army, instead of simply as auxiliaries or “with” the Army, but not in it. This affected the status of both Army nurses and members of the Army Women’s Corps stationed at Fort Monroe. Women had unofficially filled many roles in the army for years. During World War I they were allowed official roles outside of the realm of nursing for the first time. However, in WWI the women serving with the Army, both as nurses and in other roles, still were not officially members of the military, and therefore did not receive benefits such as equal rank, pay, or veterans benefits.This all changed during WWII. The Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps was established by Congress in 1942 as an auxiliary unit to the army, but in 1943 a new law was passed dropping the “Auxiliary” and women for the first time became full members of the army as part of the Women’s Army Corps in September 1943. (The Navy and Marine Corps had enlisted women during WWI). Thus by the time the first WAC officers arrived at Fort Monroe in late 1943, they were officially in the Army. According to Defender of the Chesapeake, “three second lieutenants [were] placed on duty with the post and two with the Coast Artillery School.” The first enlisted WACs arrived in January, 1944. It seems that all the enlisted women at the fort were assigned to the Coast Artillery School. There were also Army nurses stationed at Fort Monroe. These women had to wait slightly longer than the WAC to receive equal status to army men. They only received equality of rank, pay, and benefits in 1944, even though the Army Nurse Corps had been in existence since 1901. In 1944, there were twelve nurses stationed at Fort Monroe to staff the 139 bed station hospital according to an article published in the Altoona Tribune that May. The chief nurse was Lieutenant Elizabeth Steindel. She had entered the nurse corps with the (relative) rank of second lieutenant in July 1942, and was promoted to first lieutenant in October of that year. She served as chief nurse at Fort Monroe from April 6, 1943 to January 7, 1945, when was relieved by Captain Helen Jacobs in January 1945 in anticipation of being sent overseas. Steindel was still at Fort Monroe when she was promoted in Captain in April 1945. It is unknown if she was sent overseas before the war ended. Some of the other nurses at Fort Monroe during WWII were Anna P. Heistand, Margaret W. Henninger, and Lillian B. Westerfield, who all received promotions to first lieutenant in April 1945, and Lois V. Ketran, who was promoted to first lieutenant in January, 1945. Ketran was from Philadelphia and worked in the operating room at the fort’s station hospital. Steindel was from Altoona, Pennsylvania. The article mentioned above described the physical exercises Steindel had her nurses participate in so that they would be ready for both the stress of their work at Fort Monroe and the rigors of potential deployments overseas. Although women at the time were officially barred from combat, nurses realized they were likely to be in harm’s way when sent overseas and wanted to be prepared. In September 1943, nurses at Fort Monroe started participating in “military drill and calisthenics,” and also had the use of tennis courts behind their quarters, a volleyball court, and an archery set. Although the tennis court is long gone, the nurses’ quarters, Building #167, still stands on Patch Road across from the hospital. The nurses also had access to the officers’ clubs, which at the time were the Casemate Club, located in the Flagstaff Bastion, and the Beach Club, with beach access and a swimming pool, where the Paradise Ocean Club is today. The clubs also offered other off-duty activities, and the nurses were usually allowed a half day a week off post. However, with only 12 nurses, the hospital would have kept them plenty busy as well. Each nurse had a daily seven hour shift, with about one full day off a month, and the possibility of leave every four months. Although there were nurses at Fort Monroe before the WAC arrived, once they came, the WAC soon outnumbered the nurses. Although all nurses were granted officer ranks, the WAC included both enlisted and commissioned personnel. The first WACs officers arrived in late 1943. Eleven enlisted women arrived at Fort Monroe in January 1944. By the end of May, the contingent had grown to 58 WACs working for the Coast Artillery School, led by Lieutenant Mary E. Slack. The WAC was housed and fed separately from the men, and the unit included a staff of cooks, bakers, clerks, and others to make up a “normal company household” as a May 1944 Daily Press article termed it. Other women worked in “almost every non-combat duty to which soldiers are assigned… clerks and typists… artists and draftsmen … welders, parts clerks, drivers and a dispatcher in the motor pool; dark room technicians, a blueprint machine operator and motion picture projector operators.” Other positions open to them were listed to include “typists, draftsmen, artist, proofreaders, truck drivers and clerk-typists.” A February 1945 article, from the Hazelton, Pennsylvania, Plain Speaker listed other positions available in the WAC Detachment at the Coast Artillery School at Fort Monroe including linotype operator, photographer, photoengraver, retouch artist, stenographer, chauffeur, auto, file clerk, proofreader, message center clerk, messenger, and supply clerks. Fort Monroe was not the only local post to have WACs. The Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation, in Newport News, Virginia, and Fort Story, near Cape Henry, also employed WACs, while Fort Lee near Richmond was a major WAC training center. Most of the WACs at Fort Monroe were enlisted, but they still had access to recreation opportunities on post including “a modern theater [that] plays first-run motion pictures; two libraries,[…] a beach and tennis courts.” The article also specified that “two day rooms for recreation has [sic] been set up, one solely for the women’s use, and one to which they may invite their friends.” Although Fort Monroe did not receive a WAC detachment until fairly late in WWII, the women clearly made an important impact on the fort, and, as advertising slogans of the day pointed out, each one also helped to “free a man to fight.” Army WACs, wherever they were stationed, helped break down gender stereotypes by taking jobs often previously held only by men. For example, women draftsmen, who were mentioned in both newspaper articles about the WAC at Fort Monroe, were extremely rare before WWII. Fort Monroe continued to have a WAC detachment until the Women’s Army Corps was disbanded in the 1970s and women were integrated into the army. Army nurses were also breaking new ground during WWII. Even their physical fitness training at Fort Monroe was hammering away at gender stereotypes, due to the reasons given for the training described in the Altoona Tribune. The article was published only one month before D-Day, when US Army nurses were banned from landing on D-Day itself because of fears of bad press and the effect on homefront moral if a nurse was killed or wounded that day (in contrast US Army nurses had landed on D-day in North Africa the year before, and British nurses went ashore on D-Day in Normandy in British sectors). However, the article frankly admits that “Army nurses, who in this war customarily minister to the wounded under fire and take the bumps of a combat soldier in anything from jeeps to transport planes, need and are getting more physical conditioning than ever before.” It later states that “if [Lieut.] Steindel has her way they will be in condition mentally and physically to go wherever the war may take them.” Women played many important roles at Fort Monroe during WWII, from the more traditional role of nurse to newer jobs such as truck drivers and draftsmen. They contributed to both the work of Fort Monroe during WWII and to the opening of new opportunities for women. Civilian women also played important roles at Fort Monroe during World War II, such as with the fort’s YMCA and with the American Red Cross, and will be discussed in a future article.

NPS Photo Old Point Comfort LighthouseThe Old Point Comfort Lighthouse was built upon a peninsula, whose location made it pivotal in Early American History. The site is located at the entrances of the Nansemond, James, and Elizabeth Rivers. The entire peninsula, also known today as Fort Monroe, was once simply called Old Point Comfort. A quick survey of the landscape would reveal that it is riddled with structures of historical significance. The largest and most ominous being the stone and earth work known simply as Fort Monroe. While larger in size, it certainly is not the oldest structure on-site. A neighboring structure, The Old Point Comfort Lighthouse is one of the oldest standing structures found on the peninsula today. The lighthouse stands as a navigational beacon on Old Point Comfort and was thought to be active as early as 1775. Upon the formation of the United States government, lighthouses were identified as critical to the economy. The young republic starting the construction projects, one of which was being a permanent navigation aid on Old Point Comfort. Hampton Fire of 1861Following Major General Benjamin Butler’s "Contraband Decision," Fort Monroe was not only a stronghold for the Union but was also a destination of enslaved people seeking to liberate themselves at “Freedom’s Fortress.” Local Confederate forces were growing uneasy at the close proximity of the army and growing number of contrabands. By June, Confederate defenders along with most of the local population abandoned the city entirely. For a short time, Hampton was occupied by Union forces, but following a Confederate victory at Bull Run, Union soldiers were called away from Hampton and nearby Camp Hamilton. With nearby Union forces depleted, Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder sent troops to challenge the Union encampment at Newport News. He then discovered the Union’s intentions of housing "contrabands" in the abandoned homes of Hampton. Magruder realized that the proximity of Fort Monroe would prevent the Confederacy from keeping Hampton, even if it could be regained, and he was determined that Union would not benefit from Hampton’s buildings and resources. On August 7, 1861, led by Capt. Jefferson Curle Phillips, a mostly local Confederate detachment of 500 men burned the city of Hampton, leaving a desolate forest of brick foundations and chimneys. On the ruins of the once picturesque town, Union armies created camps to house contrabands from Fort Monroe. After the war, many of those men and women remained and helped rebuild the city of Hampton. |

Last updated: February 14, 2025