Excerpt from "In Full Glory Reflected." Grace Wisher was a free African American woman who was indentured as a child to the famous Star-Spangled Banner flag seamstress, Mary Pickersgill. As an African American living in the early 19th century, Grace’s story remains mostly unknown, but her role in making the flag was just as critical as those who are better represented by the historical record. African American ApprenticesGrace had been indentured as an apprentice in 1809, when she was about 10 years old, by her mother, Jenny Wisher, who was a free African American. Indenture contracts were usually signed by the child’s father, but most free African Americans in Baltimore at that time had come from rural slavery, so it is possible that Jenny’s husband was still enslaved elsewhere, or she could have been a widow. Jenny may have chosen to bind out her daughter to help with family expenses, or in hopes of providing her a better future. Economic opportunities for free African American women in Baltimore at that time were extremely limited. Most found work in domestic services, or by providing unskilled labor. An apprenticeship would offer Grace the opportunity to learn skills and a trade during a time when no formal schooling for African American children existed. Additionally, the ability to sew was a sought-after skill by employers looking for domestic help, and it also provided the possibility of self- employment.

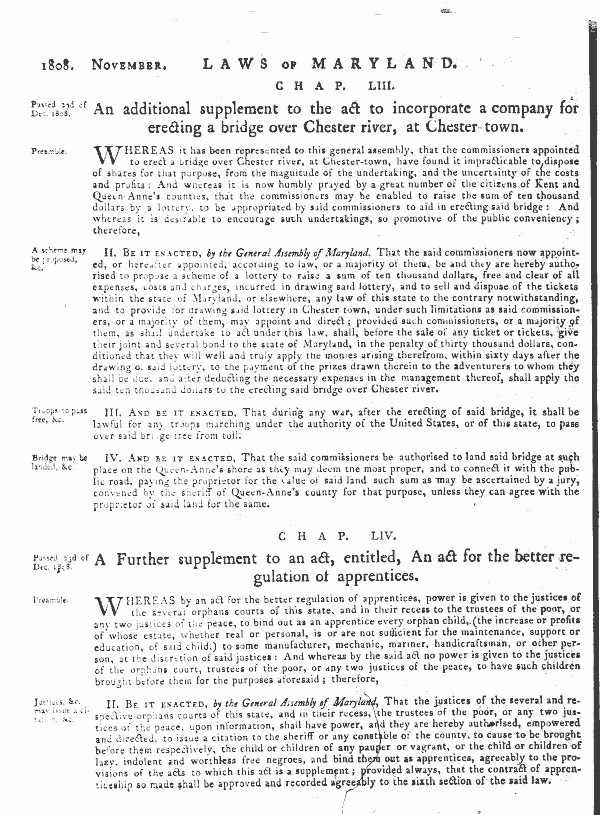

Maryland State Archives The terms of Grace’s indenture are fairly standard, with Mary promising to provide food, shelter, and clothing, and to teach Grace “the art of Housework and plain sewing.” Mary also promised to pay Grace’s mother $12 at the beginning and end of the indenture, and in exchange, Grace promised to faithfully serve and obey Mary for six years. Up until 1817, the law required that apprentices receive at least a rudimentary education during their indenture, but this provision was often ignored when it came to African American children. Additionally, some indenture arrangements substituted a cash payment in the place of educational instruction. Grace’s indenture contract did not require Mary to provide reading and writing instruction. In contrast, Mary Pickersgill did promise to provide such an education to her white apprentice in 1814, 13-year-old Mary Ann Martin. Living in Two Worlds

|

Last updated: January 5, 2021