Notes on the Origins and Evolution of African American Language

© Annette Kashif Ph.D. Associate Professor, Humanities Department, Bethune Cookman College, Daytona Beach Florida

The North American language contact situation into which Africans were plummeted was initiated in the 15th century and continued at least until the formal abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807. During this the establishment and entrenchment of the profoundly oppressive system of life-long chattel slavery dominated the colonial era of African American cultural expression. Having arrived from coastal regions covering west, central and even east Africa, the Africans in America created new ways to communicate based on the old ways back home in the “Motherland.” They came from places named Abomey, Bonny, Congo, Djenne, Gizzi, Gola, Kanem, Mande, Mina, Ngola, Oyo, Segu, Whydah, and hundreds more. They had been the literate and illiterate, peasant and artisan, bureaucrats and soldiers, royalty and subjects, aristocrats and commoners, skilled and unskilled. Their back-breaking labor and know-how were at the foundation of the development of the “new” Americas (Kashif 2001:17–19). Wherever conditions afforded, African Diasporans formed distinctive cultural complexes via their social networks and communities; through these, distinctive language and communicative practices emerged. Some of the most important sites for the development of the African Diaspora cultural complexes were plantations and maroon settlements (especially the “mountainous, forested or swampy regions of South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama (Aptheker 1939:152).”)

African Languages the 17th and 18th century Chesapeake and Low Country

As was common in all the slaveholding colonies that were serviced by the “triangular trade,” the indigenous languages spoken by the Africans enslaved in Virginia and the Low Country during the colonial period belonged overwhelmingly to the Niger-Congo family of languages. The Niger-Congo family is a large historically related group of more than 1400 languages. It extends across all regions of the Continent, south of the Sahara. To a lesser degree, Nilo-Saharan and Hamitic-Semitic, also known as Afroasiatic, language families were also present represented in colonial Virginia.

Niger-Congo is the largest, not only of the African phyla, but also of all language groups worldwide. Its most widely shared characteristics include, for example, use of mostly prefixes to classify or mark singular vs. plural nouns and verb suffixes that designate multiple action. Frequently Niger-Congo is divided into the linguistic subgroups: Atlantic, Benue-Congo, Kwa, Mande and Voltaic. From the Nilo-Saharan family, the Nilotic, Central Sudanic and Songay are subgroups; and Hamitic-Semitic has the major branches, Chadic and Cushitic.

- Atlantic branch, Fulfulde cluster with Fula, Fulani and Peul (Guinea-Cameroon), Wolof (Gambia, Senegal) and Kisi (Guinea, Liberia, Sierre Leone)

- Mande branch, Manding cluster with Bambara (Mali) and Dyula (Ivory Coast), Mandinka, Vai and Mende (Liberia and Sierre Leone)

- Kwa branch, Akan cluster with Ashanti, Fante and Twi (Ghana, Ivory Coast) and Gbe cluster, Ewe (Ghana), Aja and Fon (Togo, Benin)

- Songay branch, Songhai cluster (Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger)

- Chadic branch, Hausa (Niger, Nigeria and surrounding regions)

Africans arriving in the Upper Chesapeake and Lower James River region, in the earliest period of importation of Africans calculated that “40% were speakers of Benue-Congo languages; 40%…Mande and West Atlantic, and 10%…speakers of Kwa (Wade-Lewis 1988:110). ”Over time enslaved people in this region were imported from West African areas that are present day Senegal, Gambia Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone speaking a vast but surely-related array of Niger-Congo languages. These people probably spoke some form of the Bambara, Wolof and the Mande languages. Other Africans arriving from the area of present day Ghana and other parts of the Ivory Coast probably spoke some form of the Akan languages Ashanti, Fante and Twi.

The situation was different in the Lower Chesapeake and the Low Country where Africans arrived mostly from regions of present day eastern Nigeria to West Central Africa. These Africans would have primarily spoken languages of the Benue-Congo (Cross-River and Bantoid branches) and the Kwa subgroups of the Niger-Congo family.

From Pidgins to Creole

The language of African descendants in the Americas began shifting first, from an African polyglot status in the first generations of arrival to a period of bilingualism between a pidgin and each person’s African mother tongue. Then subsequent generations incorporated elaborated and restructured features into the pidgin, forming deep and more stable regional creoles. A creole is a pidgin or jargon that has become the native language of an entire speech community, often as a result of slavery or other population displacements. A pidgin becomes a creole as eventually people are born who use that language as their first language. Creole languages combine the language spoken by those in power, or superstrate language, and the substrate language or the language spoken by those subordinated in a cross-cultural contact. In the case of enslaved Africans coming into contact with Europeans in Africa and subsequently in the Americas, the European languages became the superstrate language, contributing most of the vocabulary to the creole languages that evolved and the African languages became the substrate languages.

These creoles were characterized mostly by mixture of English-Irish vocabulary and Niger-Congo phonology and syntax (a.k.a., grammar); they persisted throughout the centuries of enslavement. All the while, of course, a smaller number of African descendants would have frequent access to non-African speakers which afforded them opportunities to learn other languages. This is not only true for those more frequently in contact with prestige dialects of English, but also those affiliating with Native Americans. Additionally, the continuous arrival of Continent-born Africans right up until the Civil War reinforced the persistence of African languages spoken as well as the inclusion of African words in the lexicon of the evolving Creole that came to be called "Black English" and later African American English and Ebonics.

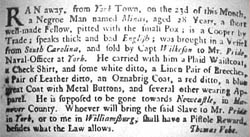

The distinctive language exhibited by African Diasporans was sometimes noted in newspaper advertisements for recapture of runaways which often described their level of English proficiency, using terms such as “broken”, “thick” and “ bad” English as in this advertisement in the Virginia Gazette (Parks), Williamsburg, July 24 to July 31, 1746.

RAN away, from York Town, on the 23d of this Month, a Negroe Man named Minas, aged 28 Years, a short well-made Fellow, pitted with the small Pox; is a Cooper by Trade; speaks thick and bad English; was brought in a Vessel from South Carolina, and sold by Capt. Wilkeson to Mr. Pride, Naval-Officer at York. He carried with him a Plaid Waistcoat, … (Costas, Virginia Runaways Minas 1746).

South Carolina records of ethnic origins of slaves are believed to be relatively accurate. Slaves were imported into South Carolina directly from Africa beginning in the late seventeenth century continuously until around 1807 when the slave trade officially ended (Curtin, 1969). The earliest wave of South Carolina slaves were Akan-Ashanti people brought in the seventeenth century by colonists from Barbados. By the late eighteenth century the preponderance of slaves around Charleston were of Kongo-Angola origins. The responses of Africans to slavery such as suicide among “Callabar negroes” (Igbo) and rebellion and insurrection among the “Coromantees” and Kongo-Angolas, resulted in a preference for slaves from Dahomey (Ewe, Fon) and the Windward Coast (Kwa, Mande and Gola speaking peoples) by the end of the slave import period (Creel, 1988-29–44). The Niger-Congo substrate language thesis for Gullah relates to historical evidence of the provenance of South Carolinian slaves.

The language of enslaved people began shifting first, from an African polyglot status in the first generations of arrival to a period of bilingualism between a pidgin and each person’s African mother tongue. Then subsequent generations incorporated elaborated and restructured features into the pidgin, forming deep and more stable regional creoles. These creoles were characterized mostly by mixture of English-Irish vocabulary and Niger-Congo sounds and grammar; they persisted throughout the centuries of enslavement.

On the North America British mainland, English-derived Atlantic Creole developed from the pidgin spoken by Africans and the British in trade contact situations much but not all of which involved slave trading. Africans sold into slavery in the West Indies first spoke a pidgin influenced by European languages, their native African languages, as well as the various Creoles spoken by Caribbean-born people of African descent. Later, Africans might be sold from the West Indies to the North American British mainland in the Chesapeake and Low Country where their language was further influenced by the English dialects spoken by the overseers on these plantations. In this fluid language environment some Africans became multi-lingual, others spoke in what the slave holder planters described as “bad English.”

Along the southeastern coast of the United States in Low Country especially the Sea Islands is a region linguists and dialect geographers refer to as the Gullah Area. The Gullah area extends from around Jacksonville, North Carolina to Jacksonville, Florida, and inland for about one hundred miles. “Gullah,” attained Creole status during the mid 1700s, and was learned and used by the second generation of slaves as their mother tongue. Presently there are African Americans living in this area who are descendants of the tribesmen brought to the New World during the time of the Slave Trade. These people still speak variations of the original creole language known as Gullah (Geraty 1997).

Contrary to the belief still held by some, Gullah is not poor or broken English. It is not a dialect of any other language, neither is it Black English. Gullah possesses every element necessary for it to qualify as a language in its own right. It has its own grammar, phonological systems, idiomatic expressions, and an extensive vocabulary.

Oral Arts and Speech Events

How people use language is often as distinctive as the grammar and vocabulary of a language. Historically and in the present, the ways Africans and African Americans use language have similarities. Scholars note that from eras as early as the Ancient Nok and Nile Valley civilizations, Africans revere and delight in the power and beauty of words/speech performance. These affinities emerged in the oral arts and speech events that African Diasporans crafted during America’s colonial era. They consoled, informed and regaled themselves through tales, rhymes, proverbs and songs.

In the present, African continuity is often evident in the verbal expressions. The “trickster” tales are among the best preserved, having been retold by Joel Chandler Harris in the “Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit” series, then through Disney’s “Songs of the South” films.

Other tales, such as the “Legend of John Henry” may be analyzed as reflexes of powerful African spiritual precepts such as Ogun. This carved plaque of the priest of Ogun, the god of war and of woodcarvers, holds a warrior’s sword and a carver’s axe.

One of the most inventive methods of communication among African Diasporans in this era was the dual code system. The hostile environment made their sincerest concerns about their freedom, humane treatment and familial relations invisible and anathema to the white ruling class; this state of affairs precipitated a system whereby such concerns could be expressed in plain view or earshot of hostile forces while masking the concerns at the same time. When they wanted to warn each other not to travel to other plantations to visit relatives or friends when a “paddy roller” (i.e., patrolman) was about, they would chant “Old Bill Rolling Pin” Georgia Sea Island Singers have preserved such songs in the repertoire.

This masking has also been documented in slave spirituals such as “Wade in the Water” and in hung appliqued quilts to notify those interested about dates, times and conditions for escaping to freedom from enslavement.

Masking itself became the subject of comical satires, known as “Puttin’ On Ol’ Massa.” The one below was told to this writer by her mother, a native of Polk county, FL:

“Ole Black Joe is hoeing a strip of land in the heat when he looks up to see clouds beginning to rumble across the sky- sighing with relief a little too loudly, he utters, “Whew, more rain, mo’ res[t].” Ol Massa walks right up on him, indignant, “What’s that you say boy?”… you know they never wanted to call a black man a man. But Old Black Joe was clever, and answered, ‘Mo rain, mo grass boss!!’