NPS Photo by John Kuehnert At Home in the BadlandsFor centuries people have lived around and sometimes in the lava country. Ancient Indian civilizations crossed the lava flows with trail cairns and related to the landscape with stories and ceremony. Spanish empire builders detoured around it and gave it the name used today. Homesteaders settled along its edges and tried to make the desert bloom. The stories of all these people are preserved in the trail cairns, petroglyphs, wall remnants, and other fragments that remain in the backcountry.

Photo by John Kuehnert. The jagged volcanic landscape of what is now El Malpais National Monument has challenged many cultures as they have interacted with it through the years. Native American Cultures have had a long and continuous tradition with this landscape, and continue to call it home thousands of years later.

Photo by John Kuehnert. A Living HomelandThe lands of El Malpais have played an important role in the cultures of Acoma, Laguna, and Zuni for thousands of years. Puebloan Cultures and their ties to the land are still evident today in places like the Zuni-Acoma Trail, which was established as a way to connect Acoma Pueblo to Zuni Pueblo.

NPS Photo. The Area is NamedEarly Spanish explorers came into what is now western New Mexico and El Malpais in search of wealth and new lands. When they encountered the rugged lava flows, they named this area El Malpais, Spanish for "the badlands" or "bad country." The phrase "el malpais" (pronounced ehl MAHL-pye-EES) already existed at the time, referring to rough and barren-looking landscapes typically formed from past volcanic activity.

Photo by Edward Curtis. New NeighborsThe Navajo, an Athabaskan-related people originally from northern Canada and Alaska, began to settle in the southwest around the 1300s. Already a hunter-gatherer society, their adoption of Spanish horses helped to dramatically expand their range. As such, their interactions with other tribes and explorers quickly increased.

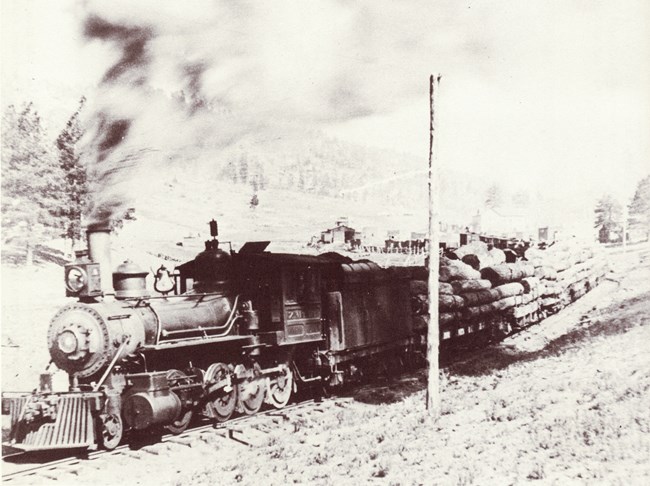

NPS Photo. Timber and Railroad TiesBy 1881, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad forever transformed the malpais area. A small settlement soon grew up around the station which took the name of Grant. With the coming of the railroad and the establishment of Fort Wingate, the sheep and cattle industries flourished. As the railroad moved further west, new towns sprang up along the right of way. Logging in the Zuni Mountains soon began in earnest to supply the railroad, Fort Wingate and the new towns along the way.

Photo by John Kuehnert Great Depression HomesteadsThe Great Depression of the 1930s drew more newcomers to the area in search of new opportunity. Western New Mexico was one of the few remaining places to build a homestead under the Homestead Act. While some families were able to make a living, others moved away and left their homesteads behind. Numerous structures still dot the El Malpais today, telling the story of people seeking to find a better life.

NPS Photo Volcano Target PracticeAlthough the El Malpais landscape witnessed historical events around it, McCartys Crater bears the scars of when the landscape was involved.

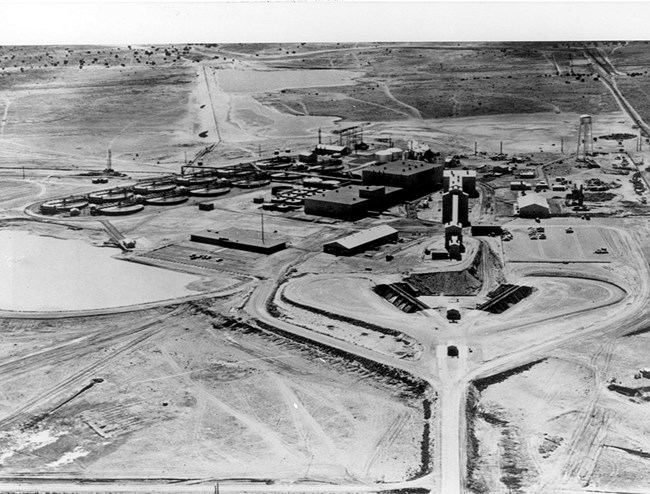

NPS Photo. Another Regional BoomThe 1950s ushered in one of the biggest changes to the malpais since the coming of the railroad: uranium. Large quantities of this chalky, yellow mineral were discovered around Grants. As demand grew during the Cold War, the town expanded rapidly to accomodate the new mine workers and their families.

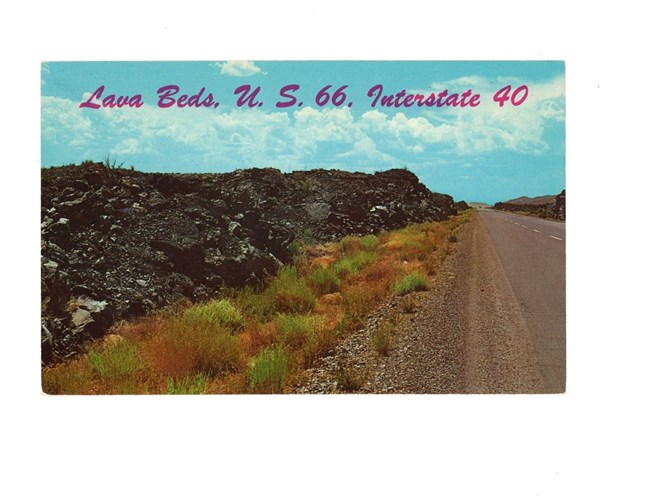

NPS Photo. Getting KicksRoute 66 contributed to the growth of many communities its path, including Grants. Just as the Tanscontinental Railroad vastly improved transportation in the 19th century, Route 66 opened much of the American west as the nation's first all-weather highway linking the midwest to California. It also allowed millions of travelers to experience the scenic beauty and human history of western states like New Mexico.

Photo by John Kuehnert El Malpais TodayBy the early 1980s, the market and demand for uranium waned. As it had many times before with different industries, this boom finally ended. In late 1987, after many years of negotiation, the malpais area finally became El Malpais National Monument.

|

Last updated: May 6, 2025