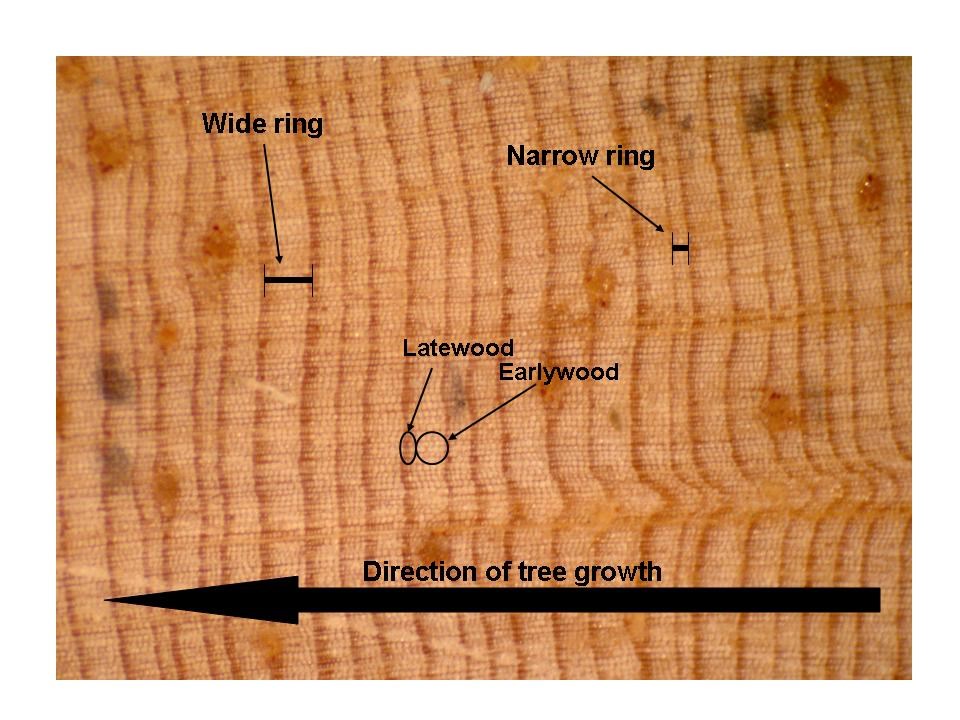

Nicoletta Browne, NPS The Present is the Key to the PastThe study of tree rings in order to obtain historical dates is known as dendrochronology. The term comes from the Ancient Greek words dendron and khronos which mean "tree" and "time," respectively. Thus, appropriately, dendrochronology involves telling time from trees! The process involves counting tree rings and comparing the patterns in these rings across different trees in order to obtain dates in a scientific manner. Trees are excellent indicators of the conditions in the environment in which they grew, and they provide researchers with decades or even centuries of "annual ecological reports" in the form of their yearly growth rings. Dendrochronology of trees and of the logs used to build structures can help us to answer important questions, such as when a structure was built, how long it was inhabited, when people left, and what environmental conditions might have caused those people to leave.As you tour the site, take time to look at (but not touch!) the remarkably intact wood beams in the Great House, still in the exact same places where ancestral Pueblo builders put them 900 years ago. The dry climate of the area has helped preserve the site remarkably well, and Aztec Ruins National Monument has more original wood than any other ancestral Pueblo site in the Southwest. This has made dendrochronology studies here especially important to constructing a timeline of human habitation in the southwest. Astronomer Andrew E. Douglass, often considered the "father of dendrochronology" due to his work correlating tree ring patterns with sunspot cycles, was in fact the first person to date beams from this site. He described Aztec Ruins as the structure "whose beams began the ancient tree-ring calendar". How a Tree Ring FormsMost of us probably learned in elementary school that the number of rings in a tree trunk corresponds to its age. Wood, like the human body, is made of cells, and every year that a tree is alive it adds a ring of new wood cells on the rim of its trunk as it grows. Little-to-no growth occurs in winter, but as soon as spring comes, a wide layer of lightweight and light-colored cells grows rapidly, producing what is known as "earlywood." As a tree nears the end of its growing season, before winter comes again, growth slows and the tree produces a thin layer of bulkier, darker colored cells that form a layer known as "latewood". One "annual ring" includes both the earlywood from the start of the growth season and the latewood from the end. In order to count tree rings, it's easiest to count the thin layers of "latewood", but you will get the same result if you count the earlywood layers; however, if you count both the light and dark layers in the same round, you will end up with a number that is twice the tree's real age!

NPS Graphic

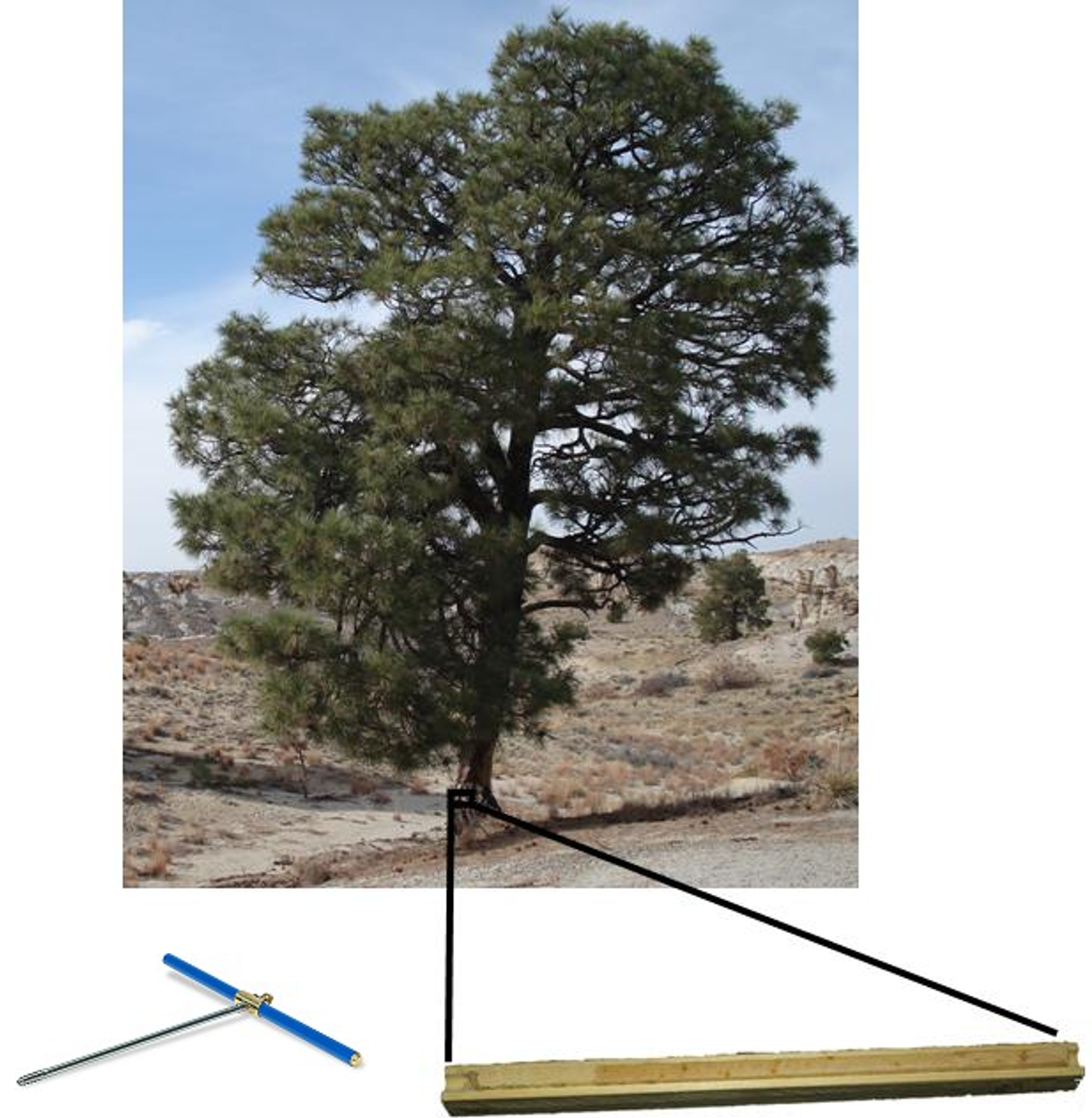

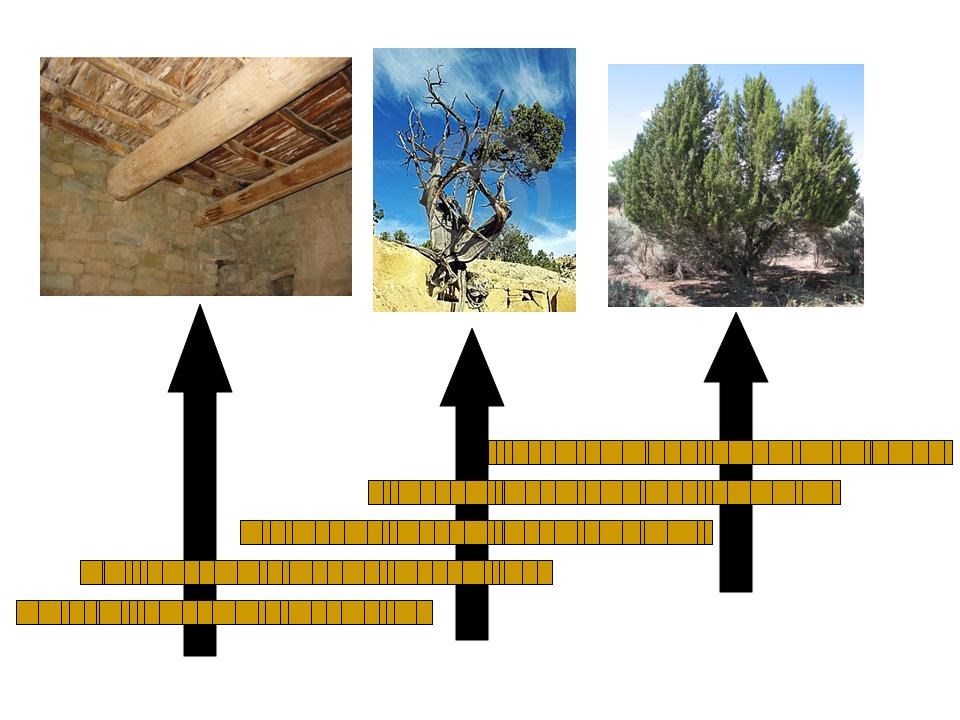

NPS Graphic Tree Rings as Environmental IndicatorsIn order to study tree ring patterns, dendrochronologists will drill and extract a "tree core" from the beam, log, or tree trunk. The tree core that is removed has the diameter of a pencil, but it runs all the way from the outer edge to the center of the trunk. This gives scientists the entire "library" of information from the oldest to the most recent times, but it avoids having to lose a large amount of the tree to destructive testing. Coring sites can be observed on the beams along the archeological trail at Aztec Ruins National Monument, as well as in the visitor center.Tree rings, in addition to providing the age of the plant, also serve as an excellent record of changes in our natural environment throughtout the years. The size of a tree ring reflects the growing conditions the tree experienced during that particular year. In warm and wet years, trees grow more, resulting in a wide ring; conversely, thinner rings usually indicate colder and drier years, when growth was more limited. Temperature and precipitation (rainfall and snowfall) are the two most important factors that influence tree ring width, but other environmental stressors can affect the pattern as well. Forest fires, insect outbreaks, nutrient availability, and competition from neighboring trees play a role in influencing the size of the rings. CrossdatingBecause tree ring patterns are influenced by climate and weather, two trees that grow in the same area under similar conditions will exhibit similar growth patterns. When studied together, patterns from living trees, dead trees, and ancient wood in the same region allow scientists to build a "chronology" that can stretch back hundreds or even thousands of years. This process of matching the ring patterns in one tree to those in another is known as "cross-dating", a method developed in the early 1900s by Andrew E. Douglass.Douglass' technique of crossdating involves matching the patterns in the oldest rings in living trees with the youngest rings in older trees, and then repeating this process with successively older lumber. The youngest rings on a dead tree or a beam will correspond to the approximate date that tree died or was cut down. This technique was a huge breakthrough, because it allowed dendrochronologists to assign dates to wooden beams from ancient structures whose exact age was previously unknown.

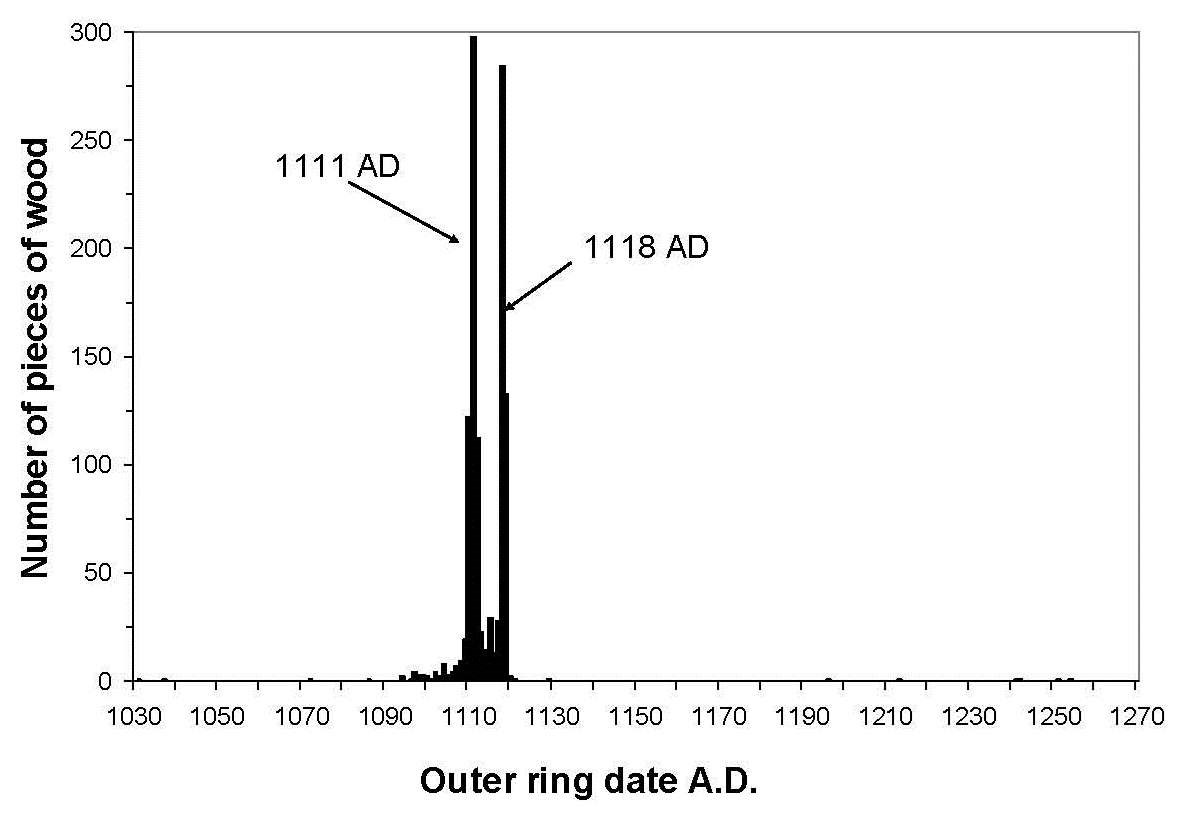

NPS Graphic Aztec Ruins Tree RingsTree rings from wood found here at Aztec Ruins can tell us about many aspects of ancestral Pueblo life. To determine the year in which a structure was built, for example, dendrochronologists examine the outermost ring of the tree beams used to build this structure, such as the roofs at Aztec West. This outermost ring represents the year the tree was cut, the last year that it was growing and alive, and this likely is the year that it was used for construction.The graph below displays the outer ring date of beams recovered from this site. The graph indicates that Aztec Ruins was built in two phases: one around 1111 AD, and another around 1118 AD. Tree rings also indicate that the structure was inhabited for about 200 years. During the 1100s and 1200s, when people lived here, they were constantly replacing broken beams in the structure. Dendrochronology records indicate that the last tree used in construction at Aztec Ruins was cut in 1269 AD. Ring patterns not only tell us what year the tree was cut down, but we can also learn during which season the ancestral Pueblo people harvested their wood. In the rooms that mostly contain beams dated at 1118 AD, we find a few that give a date of 1119 AD. This indicates that harvesting actually took place during the early spring of 1119 AD, before most trees had begun to produce a growth layer that would correspond to the year 1119 AD. The very few trees that would have started growing for the season do show this ring. Why would they have harvested trees in the early spring? That is before sap starts to flow, and harvesting trees before sap flows results in stronger and more durable beams. Tree rings from ancient wooden beams contain valuable historic climate data. By studying which tree rings are wide and which ones are narrow, for example, we have learned that the ancestral Pueblo people weathered many droughts of several years during the two centuries in which they lived here. Two especially severe droughts occurred. The first began around 1130 AD and lasted between 50 and 60 years; this drought may have encouraged people to migrate from Chaco Canyon, where there is relatively little water, to the Animas River valley. The second one began around 1276 AD and persisted at least for 24 years. There is evidence of crop failure and depletion of food supplies during this time. This second severe drought is thought to have been a major factor in the departure of the ancestral Pueblo peoples from the Four Corners by 1300 AD; since that time, their descendents have lived on the Hopi Mesas in Arizona, in central and central-west New Mexico, and (in one case) near present-day El Paso, Texas.

NPS Graphic

NPS Photo The Past as the Key to the FutureDendrochronology is an interdisciplinary science, meaning that it employs techniques and methods from seveal different scientific fields. In addition to archaeologists, it has also been very useful for ecologists, foresters, climatologists, and historians. Tree rings are, for example, used to reconstruct how forests looked like in the past and provide educated guesses as to how often forest fires, insect outbreaks, and other natural disturbances occurred. This analysis not only reveals what past conditions were like, but it also provides scientists with ideas about how changes in environmental conditions and processes may play out in the future.Even today, archaeologists at Aztec Ruins continue to uncover ancient remnants of the wood used to build these impressive structures. Who knows what tree rings still have yet to teach us about the lives of the people who once lived here! National Parks in the History of Science VideoAztec Ruins, along with Chaco Culture and Mesa Verde, was the site of many foundational developments in the field of geochronology. You can view a video on these developments below.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Trees are living archives of information. Scientists around the world use tree rings to understand past climates, ecosystems, and cultures. |

Last updated: September 17, 2022