Part of a series of articles titled Telling Time at Grand Canyon National Park.

Article

Geologic Timescale, Geologic Dating Techniques, and Numeric Ages

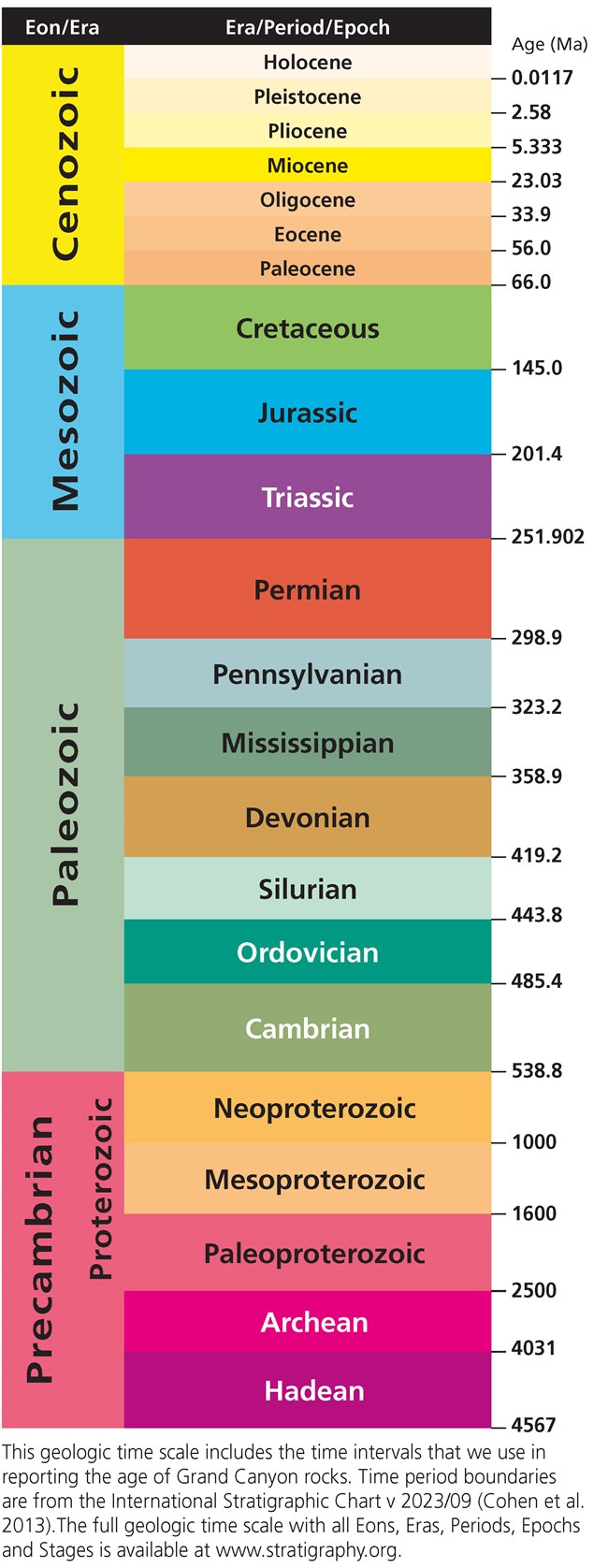

Time period boundaries are from the International Stratigraphic Chart v 2020/01 (Cohen et al. 2013, updated).

Introduction

Geologists have many different ways to tell time. Some determine the order of events and others identify specific times in the past when geologic events took place. Geologists report the age of rock units and geologic events with descriptive terms and numeric ages. An understanding of how geologists tell time is important to understanding the age of rocks exposed in Grand Canyon National Park.

Geologic Timescale

Historians identify major periods in human history and broad global eras with descriptive terms such as the Stone Age or the Renaissance that do not rely on specific dates but relate various periods of history that are more or less defined in the public’s mind. But historians have an advantage over geologists because people are more familiar with these terms and can infer the period of time from them.

Geologists have similar temporal subdivisions in the Geologic Timescale (Figure 7). The Paleoproterozoic, Mississippian, and Pliocene all define spans of time, but most laypeople are less familiar with these terms nor could they put them in chronological order.

The Geologic Timescale (Figure 7) was first constructed by geologists in the 1800s before the discovery of radioactive decay that provides the clock used in many numeric dating techniques. Hence, it was originally based entirely on relative dating and stratigraphic principles, such as the principles of superposition, lateral continuity, and the change in fossil assemblages through time (faunal succession). Geologists depend on index fossils and fossil biozones to help constrain the relative ages of sedimentary rocks containing fossils. Index fossils are fossils or assemblages of fossils that are diagnostic of a particular time in Earth history. Fossil biozones are stratigraphic units defined by the fossils that they contain. Most of the Paleozoic sedimentary rocks exposed in Grand Canyon contain a rich fossil record that provides important information about their age.

The Geologic Timescale is regularly updated and refined. This study utilizes the most recent version of the International Stratigraphic Chart (v 2020/01).

The primary subdivisions of geologic time (Figure 7) follow the major events in the evolution of life and history of the planet:

-

Hadean Eon (referring to the underworld)

-

Archean Eon (beginning life)

-

Proterozoic Eon (earlier life)

-

Paleozoic Era (old life)

-

Mesozoic Era (middle life)

-

Cenozoic Era (recent life).

Grand Canyon contains important rock records from the Proterozoic and the Paleozoic.

Geologic Dating Techniques

Scientists use two major categories of geologic dating techniques, to determine how old rocks are and identify major intervals in Earth’s history:

- Relative dating

- Numeric (or absolute) dating,

Relative Dating

Relative age dating determines the order in which a sequence of geologic events occurred (e.g., bottom-to-top sequential deposition of sedimentary strata, then carving of a geologically young canyon through those strata), but cannot determine how long ago events happened.

Numeric Ages

Numeric ages identify when in years specific events occurred. This term is used instead of absolute age because the ages are refined and updated as radiometric dating techniques improve

A variety of radioactive elements, each with its characteristic decay rate (and half life), have been used for numeric dating. Different elements can be used for different time spans, and/or to cross-check numeric dates obtained via other methods. Geologists identify these techniques by their radioactive parent and stable daughter elements and have used many of them, including uranium-lead (U-Pb), potassium-argon (K-Ar), rubidium-strontium (Rb-Sr), and rhenium-osmium (Re-Os), to determine numeric ages of Grand Canyon rocks.

Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks

For igneous rocks, radiometric age determinations directly measure when the minerals crystallized from a magma, essentially at the same time that the rock formed. For metamorphic rocks, most age determinations reflect the time when minerals formed during metamorphism or the time of cooling following metamorphism.

Sedimentary Rocks

Sedimentary rocks are harder to date because most grains within them were not formed when the sediment was deposited. But several circumstances are particularly helpful in determining the age of a sedimentary rock. Some sedimentary rocks include discrete layers of volcanic ash containing datable igneous minerals that were deposited with the sediment as ash fall deposits from a distant eruption (Figure 8A). Ash may also be reworked by rivers or oceans after its initial deposit. In these cases, the age of the ash bed indicates the maximum age for the enclosing sedimentary rock since the original ash fallout deposit must have occurred before it was reworked into the sedimentary rock. Another circumstance is when an igneous intrusion cuts across a sedimentary unit (Figure 8B). In this case, the age of the dike provided a minimum age for the sedimentary rock.

Figure 8A. Sedimentary rocks can be dated directly if they contain an igneous layer that was deposited within the sedimentary layers, like a volcanic ash. This 1-cm-thick ash bed in the uppermost Chuar Group provides a direct date of 729 ± 0.9 million years.

Photo by Laurie Crossey.

Figure 8B. The age of sedimentary rocks can be bracketed by cross-cutting igneous rocks; in this case, the black dike cuts across, and hence, is younger than the reddish Hakatai Shale. This dike is dated as 1,104 ± 2 million years old.

Photo by Laurie Crossey.

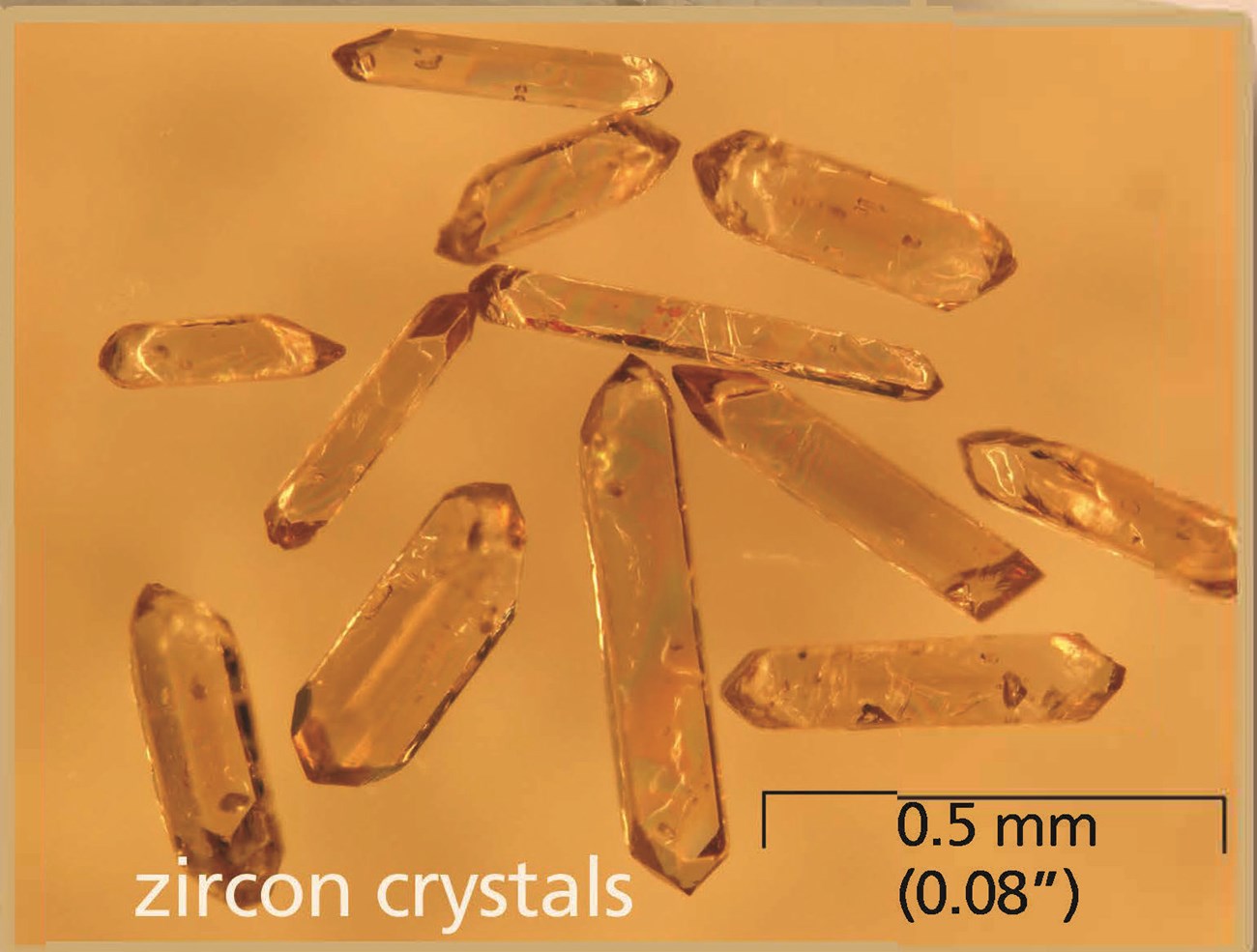

Dating detrital zircons (zircon crystals that eroded from igneous rocks and deposited in sedimentary rocks) (Figure 8C) is another technique that can help constrain the numeric age for sedimentary rocks by providing the maximum depositional age.

Figure 8C. The age of sedimentary rocks can also be bracketed by the age the youngest dated sedimentary grains (detrital zircon) within the sediment.

Every analytical method used in scientific investigations, including radiometric age determinations, has a certain analytical error or precision that is expressed as a plus or minus from the measured age. Precision is different than accuracy, which is how close the measured date is to the real or actual age. Different dating techniques have different precisions due to limitations of the analytical equipment, while accuracy depends on a variety of geologic factors as well as the soundness of the relevant geological observations and interpretations. Geologists who use radiometric age determinations strive to both accurately and precisely measure geologic events by improving laboratory methods, controlling for geologic complexities, and applying multiple dating techniques when possible. Ages reported in the more recent geologic literature are commonly more precise and more accurate than ages published in the older literature due to advances in dating techniques.

Each new numeric age within a stratigraphic sequence brackets the age of the units above and below it. Thus each new date provides cross-checks, and leads to increasingly well-known ages and durations.

Learn More

To learn more about the age of Grand Canyon’s rocks, please see:

Karlstrom, K., L. Crossey, A. Mathis, and C. Bowman. 2021. Telling time at Grand Canyon National Park: 2020 update. Natural Resource Report NPS/GRCA/NRR—2021/2246. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2285173. [IRMA Portal]

Authors

- Dr. Karl Karlstrom is a Distinguished Professor of Geology at the University of New Mexico with a specialty in tectonics; he has researched Grand Canyon rocks of all ages over the past 35 years.

- Dr.Laurie Crossey is a Professor of Geology and Geochemistry at the University of New Mexico who has worked on Grand Canyon rocks and water issues over the past 20 years.

- Allyson Mathis is a Research Associate with the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, and a geologist by training. Allyson worked for the National Park Service at Grand Canyon National Park from 1999 to 2013.

- Carl Bowman is a retired air quality specialist, formerly of Grand Canyon National Park, where he worked in various positions between 1980 and 2013.

References

-

Babcock, R. S. 1990. Precambrian crystalline core, in S. S. Beus and M. Morales, editors. Grand Canyon geology, first edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

-

Billingsley, G. H., and S. S. Beus. 1985. The Surprise Canyon Formation, an Upper Mississippian and Lower Pennsylvanian (?) rock unit in the Grand Canyon, Arizona. U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. Bulletin 1605: A27–A33.

-

Breed, W.J., and Ford, T.D., 1973, Chapter Two-and-a-half of Grand Canyon history, or the Sixty Mile Formation: Plateau, v. 46, no. 1, p. 12-18.

-

Cohen, K. M., S. C. Finney, P. L. Gibbard, and J.-X. Fan. 2013; updated in 2020. The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart. Episodes 36: 199–204. Available at https://stratigraphy.org/icschart/ChronostratChart2020-01.pdf (accessed 01 Jun 2020).

-

Dehler, C., G. Gehrels, S. Porter, M. Heizler, K. Karlstrom, G. Cox, L. Crossey, and M. Timmons. 2017. Synthesis of the 780–740 Ma Chuar, Uinta Mountain, and Pahrump (ChUMP) groups, western USA: Implications for Laurentia-wide cratonic marine basins. Geological Society of America Bulletin 129(5–6): 607–624. doi: 10.1130/B31532.1.

-

Francischini, H., S. G. Lucas, S. Voight, L. Marchetti, V. L. Santucci, C. L. Knight, J. R. Wood, P. Dentzien-Dias, and C. L. Schultz. 2019. On the presence of Ichniotherium in the Coconino Sandstone (Cisuralian) of the Grand Canyon and remarks on the occupation of deserts by non-amniote tetrapods. Paläontologische Zeitschrift online: 119.

-

Gehrels, G. E., R. Blakey, K. E. Karlstrom, J. M. Timmons, S. Kelley, B. Dickinson, and M. Pecha. 2011. Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology of Paleozoic strata in the Grand Canyon, Arizona. Lithosphere 3: 183–200. doi: 10.1130/L121.1.

-

Hawkins, D. P., S. A. Bowring, B. R. Ilg, K. E. Karlstrom, and M. L. Williams. 1996. U-Pb geochronologic constraints on Proterozoic crustal evolution. Geological Society of America Bulletin 108: 1167–1181.

-

Hintze, L. F. and B. J. Kowallis. 2009. Geologic History of Utah. Brigham Young University Geology Studies Special Publication 9, Provo, Utah.

-

Holland, M. E., K. E. Karlstrom, G. Gehrels, O. P. Shufeldt, G. Begg, W. L. Griffin, and E. Belousova. 2018. The Paleoproterozoic Vishnu basin in southwestern Laurentia: implications for supercontinent reconstructions, crustal growth, and the origin of the Mojave province: Precambrian Research 308: 1–17.

-

Ilg, B. R., K. E. Karlstrom, D. Hawkins, and M. L. Williams. 1996. Tectonic evolution of Paleoproterozoic rocks in Grand Canyon, Insights into middle crustal processes. Geological Society of America Bulletin 108: 1149–1166.

-

Karlstrom, K. E., S. A. Bowring, C. M. Dehler, A. H. Knoll, S. Porter, Z. Sharp, D. Des Marais, A. Weil, J. W. Geissman, M. Elrick, M. J. Timmons, K. Keefe, and L. Crossey. 2000. Chuar Group of the Grand Canyon: Record of breakup of Rodinia, associated change in the global carbon cycle, and ecosystem expansion by 740 Ma. Geology 28: 619–622.

-

Karlstrom, K. E., and L. J. Crossey. 2019. The Grand Canyon Trail of Time companion: Geology essentials for your canyon adventure. Trail of Time Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

-

Karlstrom, K. E., J. Hagadorn, G. G. Gehrels, W. Mathews, M. Schmitz, L. Madronich, J. Mulder, M. Pecha, D. Geisler, and L. J. Crossey. 2018. U-Pb dating of Sixtymile and Tonto Group in Grand Canyon defines 505–500 Ma Sauk transgression. Nature Geoscience 11: 438–443.

-

Karlstrom, K. E., S. S. Harlan, M. L. Williams, J. McLelland, J. W. Geissman, and K. I. Ahall. 1999. Refining Rodinia: Geologic evidence for the Australia–Western U.S. connection for the Proterozoic. GSA Today 9(10): 1–7.

-

Karlstrom, K. E., B. R. Ilg, M. L. Williams, D. P. Hawkins, S. A. Bowring, and S. J. Seaman. 2003. Paleoproterozoic rocks of the Granite Gorges. Pages 9–38 in S. S. Beus and M. Morales, editors. Grand Canyon geology, second edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

-

Karlstrom, K. E., M. T. Mohr, M. Schmitz, F. A. Sundberg, S. Rowland, J. Hagadorn, J. R. Foster, L. J. Crossey, C. Dehler, and R. Blakey. 2020. Redefining the Tonto Group of Grand Canyon and recalibrating the Cambrian timescale. Geology 48: 425–430. doi: 10.1130/G46755.1.

-

Karlstrom, K., S. Semken, L. Crossey, D. Perry, E. D. Gyllenhaal, J. Dodick, M. Williams, J. Hellmich-Bryan, R. Crow, N. Bueno Watts, and C. Ault. 2008. Informal geoscience education on a grand scale: The Trail of Time exhibition at Grand Canyon. Journal of Geoscience Education 56: 354–361.

-

Karlstrom, K. E., and J. M. Timmons. 2012. Many unconformities make one “Great Unconformity” in J. M. Timmons and K. E. Karlstrom, editors. Grand Canyon geology: 2 billion years of Earth history. Geological Society of America Special Paper 489, Boulder, Colorado.

-

Lillie, Robert J. 2005. Parks and plates: The geology of our national parks, monuments, and seashores. W. W. Norton, New York, New York.Mathis, A. 2006. Grand Canyon yardstick of geologic time: A guide to the canyon’s geologic history and origin. Grand Canyon Association, Grand Canyon, Arizona, USA.

-

Mathis, A. and C. Bowman. 2005a. What’s in a number?: Numeric ages for rocks exposed within Grand Canyon. Nature Notes XXI(1). Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona.

-

Mathis, A. and C. Bowman. 2005b. What’s in a number?: Numeric ages for rocks exposed within Grand Canyon. Part 2. Nature Notes, v. XXI(2). Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona.

-

Mathis, A. and C. Bowman 2006a. The grand age of rocks Part 1— Numeric ages for rocks exposed within Grand Canyon. Boatman’s Quarterly Review 19(1):27–29. Grand Canyon River Guides, Flagstaff, Arizona. Available at https://www.gcrg.org/bqr/pdfs/19-1.pdf (accessed 01 Jun 2020).

-

Mathis, A. and C. Bowman 2006b. The grand age of rocks Part 2—Grand Canyon’s three sets of rocks. Boatman’s Quarterly Review: Grand Canyon River Guides. 19(2):19–23. Grand Canyon River Guides, Flagstaff, Arizona. Available at https://www.gcrg.org/bqr/pdfs/19-2.pdf (accessed 01 Jun 2020).

-

Mathis, A. and C. Bowman 2006c. The grand age of rocks Part 3—Geologic dating techniques. Boatman’s Quarterly Review 19(4):19–23. Grand Canyon River Guides, Flagstaff, Arizona. Available at https://www.gcrg.org/bqr/pdfs/19-4.pdf (accessed 01 Jun 2020).

-

Mathis, A. and Bowman, C. 2007. Telling Time at Grand Canyon National Park. Park Science, 24(2): 78–83. Available at https://irma.nps.gov/Datastore/DownloadFile/615879 (accessed 07 May 2020).

-

McKee, Edwin D. 1931. Ancient landscapes of the Grand Canyon region. Northland Press, Flagstaff, Arizona.

-

McKee, Edwin D. 1969. Stratified rocks of the Grand Canyon. In The Colorado River Region and John Wesley Powell. USGS Professional Paper 669-B. Washington DC. Available at https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0669/report.pdf (accessed 11 May 2020).

-

McKee, E. D. 1975. The Supai Group — Subdivision and nomenclature. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1395-J, Washington, D.C , Washington, D.C.McKee, E. D., and C. E. Resser. 1945. Cambrian history of the Grand Canyon region. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 563.

-

Mohr, M.T., M.D. Schmitz, N.L. Swanson-Hysell, K.E. Karlstrom; F.A. Macdonald, M.E. Holland, Y. Zhang, N. Anderson. In review. High-Precision U-Pb geochronology links magmatism in the SW Laurentia Large Igneous Province and Midcontinent Rift.

-

Mulder, J. A., K. E. Karlstrom, K. Fletcher, M. T. Heizler, J. M. Timmons, L. J. Crossey, G. E. Gehrels, and M. Pecha. 2017. The syn-orogenic sedimentary record of the Grenville Orogeny in southwest Laurentia. Precambrian Research 294: 33–52.

-

National Park Service. 2017. Foundation Statement. Grand Canyon National Park. Grand Canyon, Arizona.

-

Perry, D. L. 2012. What makes learning fun? Principles for the design of Intrinsically motivating museum exhibits. AltaMira Press, Lanham, Maryland.

-

Powell, J. W. 1875. Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and its tributaries. Explored in 1869, 1870, 1871, and 1872, under the direction of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., USA.

-

Rooney, A. D., J. Austermann, E. F. Smith, Y. Li, D. Selby, C. M. Dehler, M. D. Schmitz, K. E. Karlstrom, and F. A. Macdonald. 2018. Coupled Re-Os and U-Pb geochronology of the Tonian Chuar Group, Grand Canyon. Geological Society of America Bulletin 130(7–8): 1085–1098.

-

Santucci, V. L., and J. S. Tweet, editors. 2020. Grand Canyon National Park: Centennial paleontological resource inventory (non-sensitive version). Natural Resource Report NPS/GRCA/NRR—2020/2103. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

-

Schuchert, Charles. 1918. The Cambrian of the Grand Canyon of Arizona. American Journal of Science (Series 4) 45: 368.

-

Shufeldt, O. P., K. E. Karlstrom, G. E. Gehrels, and K. Howard. 2010. Archean detrital zircons in the Proterozoic Vishnu Schist of the Grand Canyon, Arizona: Implications for crustal architecture and Nuna reconstructions. Geology 38: 1099–1102.

-

Spamer, Earle E. 1989. The development of geological studies in the Grand Canyon. Tryonia. Miscellaneous Publications of the Department of Malacology. The Academy of Sciences of Philadelphia No. 17. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

-

Timmons, J. M., and K. E. Karlstrom, editors. 2012. Grand Canyon geology: 2 billion years of Earth history. Geological Society of America Special Paper 489. Boulder, Colorado.

-

Timmons, J. M., K. E. Karlstrom, M. T. Heizler, S. A. Bowring, G. E. Gehrels, and L. J. Crossey. 2005. Tectonic inferences from the ca. 1255–1100 Ma Unkar Group and Nankoweap Formation, Grand Canyon: Intracratonic deformation and basin formation during protracted Grenville orogenesis. Geological Society of America Bulletin 117(11–12): 1573–1595.

-

Whitmeyer, S., and K. E. Karlstrom. 2007. Tectonic model for the Proterozoic growth of North America.Geosphere 3(4): 220–259.

Glossary

-

Absolute age: a numeric age in years. Numeric age is the preferred term.

-

Accuracy: measure of how close a numeric date is to the rock’s real age.

-

Angular unconformity: a type of unconformity or a gap in the rock record where horizontal sedimentary layers (above) were deposited on tilted layers (below). At Grand Canyon, horizontal layers of the Layered Paleozoic Rocks lie on top of the tilted rocks of the Grand Canyon Supergroup.

-

Basalt: a dark, fine-grained volcanic (extrusive igneous) rock with low silica (SiO2) content.

-

Biochron: length of time represented by a fossil biozone.

-

Carbonate: sedimentary rock such as limestone or dolostone largely composed of minerals containing carbonate (CO3-2) ions.

-

Contact: boundary between two bodies of rock or strata.

-

Daughter isotope: the product of decay of a radioactive parent isotope.

-

Detrital: pertaining to grains eroded from a rock that were transported and redeposited in another.

-

Dike: a wall-like (planar) igneous intrusion that cuts across pre-existing layering.

-

Diabase: a dark igneous rock similar in composition to basalt but with coarser (larger) grain size.

-

Disconformity: a type of unconformity or gap in the rock record between two sedimentary layers caused by erosion or nondeposition where the layers are parallel to one another.

-

Dolomite: the mineral calcium magnesium carbonate CaMg(CO3)2 that usually forms when magnesium-rich water alters calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

-

Dolostone: a rock predominantly made of dolomite.

-

Eon: longest subdivision of geologic time in the Geologic Timescale; for example, the Proterozoic Eon.

-

Era: second-longest subdivision of geologic time below eon in the Geologic Timescale; for example, the Paleozoic Era.

-

Epoch: fourth-longest subdivision of geologic time, shorter than a period and longer than a stage in the Geologic Timescale; for example, the Pleistocene Epoch.

-

Faunal succession: the change in fossil assemblages through time which has a specific, reliable order.

-

Foliation: tectonic layering in metamorphic rocks caused by parallel alignment of minerals due to compression.

-

Formation: the fundamental unit in stratigraphy and geologic mapping that consists of a set of strata with distinctive rock characteristics. Formations may consist of a single rock type (e.g., Tapeats Sandstone or Redwall Limestone), or a mixture of rock types (e.g. Hermit Formation, which includes sandstone, mudstone, and shale).

-

Fossil: evidence of life in a geologic context usually consisting of the remains or traces of ancient life.

-

Fossil biozone: stratigraphic unit defined by a distinctive assemblage of fossils.

-

Ga: giga annum: billion years; in this paper, our usage implies billion years before present (or ago) when used for numeric ages.

-

Gneiss: a high-grade metamorphic rock with strong foliation and light and dark bands of minerals.

-

Granite: a high silica (SiO2) pink to white intrusive igneous rock composed mainly of feldspar and quartz.

-

Granodiorite: a gray intrusive igneous rock composed of feldspar, quartz, biotite, and hornblende with less silica (SiO2) than granite.

-

Group: a sequence of two or more related formations, with a stratigraphic rank higher than formation; for example, the Chuar Group is made up of the Nankoweap, Galeros, and Kwagunt formations.

-

Igneous rock: a rock that solidified from molten material (magma or lava), either within the Earth (as an intrusive or plutonic rock) or after eruption onto the Earth’s surface (as an extrusive or volcanic rock).

-

Inclusion: a fragment of an older rock within a younger rock.

-

Index fossil: a fossil or assemblage of fossils that is diagnostic of a particular time in Earth history.

-

Intrusion: an igneous rock body that crystallized underground. Intrusions may have any size or shape; large ones are known as plutons, thin ones parallel to layering are known as sills, and thin ones that cut across layering are called dikes.

-

Isotope: one of the forms of a chemical element (with the same atomic number) that contains a different number of neutrons.

-

Lateral continuity: a geologic principle that sedimentary rocks extend laterally, and that if they are now separated due to erosion, they were once laterally continuous; for example, the Kaibab Formation on the South Rim is laterally continuous with the Kaibab Formation on the North Rim.

-

Lava: molten rock erupted onto the Earth’s surface.

-

Ma: mega annum: million years; in this paper, our usage implies million years before present (or ago) when used for numeric ages.

-

Magma: molten or partially molten rock material formed within the Earth.

-

Member: a subdivision of a formation, usually on the basis of a different rock type or fossil content; for example, the Hotauta Conglomerate is a member of the Bass Formation.

-

Metamorphic rock: a rock formed by recrystallization under intense heat and/or pressure, generally in the deep crust.

-

Monadnock: a bedrock island that sticks above the general erosion level.

-

Nonconformity: an unconformity or gap in the rock record where sedimentary layers directly overlie older and eroded igneous or metamorphic rocks.

-

Numeric age: age of a rock in years (sometimes called absolute age).

-

Numeric age determination: measurement of the age of a rock in years, often through the use of radiometricdating techniques.

-

Orogeny: mountain building event, usually in a collisional tectonic environment.

-

Parent isotope: the radioactive isotope that decays to a daughter isotope.

-

Pegmatite: a type of intrusive igneous rock usually of granitic composition with large crystal size.

-

Period: third-longest subdivision of geologic time shorter than an era and longer than an epoch in the Geologic Timescale; for example, the Permian Period.

-

Plate tectonics: theory that describes the Earth’s outer shell as being composed of rigid plates that move relative to each other causing earthquakes, volcanism, and mountain building at their boundaries.

-

Pluton: large intrusion of magma that solidified beneath the Earth’s surface.

-

Precambrian: the period of time before the Cambrian Period that includes the Proterozoic, Archean, and Hadean eons and represents approximately 88% of geologic time.

-

Precision: measure of the analytical uncertainty or reproducibility of an age determination.

-

Proterozoic: geologic eon dominated by single-celled life extending from 2,500 to 541 million years ago; divided into the Paleoproterozoic (1,600–2,500 Ma), Mesoproterozoic (1,000–1,600 Ma), and Neoproterozoic (541–1,000 Ma) eras.

-

Radioactive decay: the process by which the nuclei of an unstable (radioactive) isotope lose energy (or decay) by spontaneous changes in their composition which occurs at a known rate for each isotope (expressed as a half life); for example, the parent uranium (238U) isotope decays to the daughter lead (206Pb) isotope with a half life of 4.5 billion years.

-

Radiometric dating: age determination method that uses the decay rate of radioactive isotopes and compares the ratio of parent and daughter isotopes within a mineral or rock to calculate when the rock or mineral formed.

-

Regression: geologic process that occurs when the sea level drops relative to the land level; for example, by sea level fall and/or uplift of the land, causing the withdrawal of a seaway from a land area.

-

Relative time: the chronological ordering of a series of events.

-

Rift basin: a basin formed by stretching (extension) of the Earth’s crust. Rift basins are linear, fault-bounded basins that can become filled with sediments and/or volcanic rocks.

-

Rodinia: a Neoproterozoic supercontinent that was assembled about 1.0 Ga (during Unkar Group time) and rifted about 750 Ma (during Chuar Group time).

-

Sedimentary rock: a rock composed of sediments such as fragments of pre-existing rock (such as sand grains), fossils, and/or chemical precipitates such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3).

-

Schist: a metamorphic rock with platy minerals such as micas that have a strong layering known as foliation or schistosity.

-

Silica: silicon dioxide (SiO2), a common chemical “building block” of most major rock-forming minerals, either alone (i.e., as quartz) or in combination with other elements (in clays, feldspars, micas, etc.).

-

Sill: a sheet-like igneous intrusion that is parallel to pre-existing layering.

-

Snowball Earth: a hypothesis that the Earth’s surface became completely or mostly frozen between 717 and 635 million years ago.

-

Stage: a short subdivision of geologic time in the Geologic Timescale often corresponding to the duration of a fossil assemblage.

-

Stratigraphic age: the era, period, epoch, or stage a rock is assigned to based on its fossil biozones or numeric age.

-

Stratigraphy: the study of layered rocks (strata), which usually consist of sedimentary rock layers, but may also include lava flows and other layered deposits.

-

Stromatolite: a fossil form constructed of alternating layers (mats) of microbes (algal or bacterial) and finegrained sediment.

-

Subduction zone: a plate boundary where two plates converge and one sinks (subducts) beneath the other.

-

Supergroup: a sequence of related groups, with a higher stratigraphic rank than group; for example, the Grand Canyon Supergroup consists of the Unkar and Chuar groups.

-

Superposition: principle of geology that the oldest layer in a stratigraphic sequence is at the bottom, and the layers get progressively younger upwards.

-

Tectonics: large-scale processes of rock deformation that determine the structure of Earth’s crust and mantle.

-

Trace fossil: a sign or evidence of past life, commonly consisting of fossil trackways or burrows.

-

Transgression: a movement of the seaway across a land area, flooding that land area because of a relative sea level rise and/or land subsidence.

-

Travertine: calcium carbonate (CaCO3) precipitated by a spring; most travertine deposits also contain some silica.

-

Unconformity: a rock contact across which there is a time gap in the rock record formed by periods of erosion and/or nondeposition.

-

Volcanic ash: small particles of rock, minerals, and volcanic glass expelled from a volcano during explosive eruptions. Volcanic ash may be deposited great distances (even hundreds of miles or kilometers) from the volcano in especially large eruptions.

-

Yavapai orogeny: mountain building period that occurred approximately 1,700 million years ago when the Yavapai volcanic island arc collided with proto-North America.

-

Zircon: a silicate mineral (ZrSiO4) that often forms in granite and other igneous rocks and incorporates uranium atoms, making it useful for radiometric dating.

Photos and Illustrations

Related Links

-

Grand Canyon National Park (GRCA), Arizona—[GRCA Geodiversity Atlas] [GRCA Park Home] [GRCA npshistory.org]

Last updated: January 30, 2024