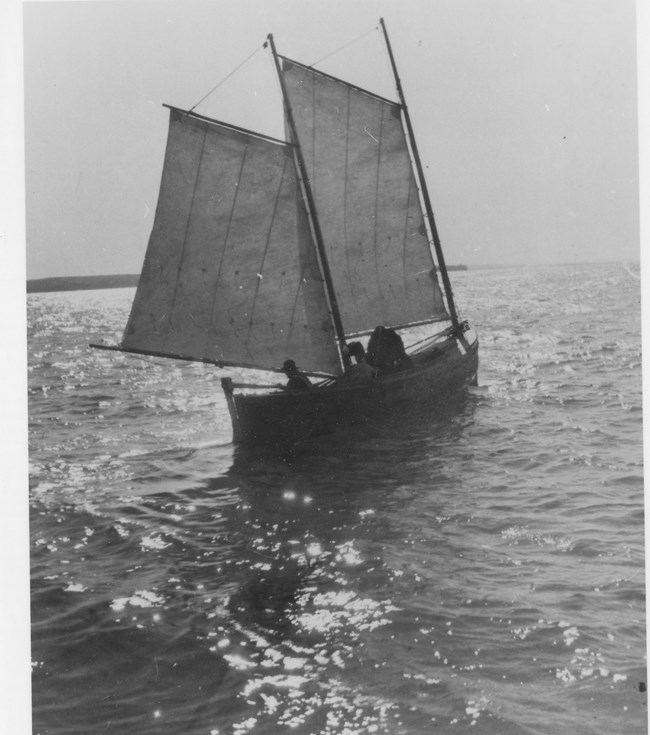

NPS Photo/M. Carlson Navigating Great WaterThe Ojibwe called the big lake Gitchigumi, or, “Great Water,” in deference to the lake they believed had the power to provide ample harvests of fish or to cast a storm upon them capable of destroying entire villages. It was believed a great sea monster lurked underneath the surface, a sort of lynx-like creature known as Mishi Peshu which represented the raw power, mystery, and most importantly, the innate danger that came from challenging the sacred waters. The beast demanded respect and like the lake itself, was not to be taunted or provoked. Only the bravest, or perhaps the most insane warriors set out in their canoe without first paying homage to the lake’s Great Spirit.

NPS Photo Theodore Karamanski, author of Great Lakes Navigation and Navigational Aids Historical Context Study, wrote “Nothing better symbolizes the drama of American history than a lighthouse on a storm-washed shore.” It is lighthouses, Karamanski believes, which have played a vital and irreplaceable role in American history. By 2013, more than 400 lighthouses stood upon the international shores of the five Great Lakes with more than 262 structures located on the American side. From the earliest days of Great Lakes shipping to the present, sailors of all skill levels have had to be concerned with delivering cargo and passengers safely from one port to another on the big lake. Before the advent of lighthouses, mariners sailing Lake Superior’s waters relied on simple, crudely drawn maps or simple celestial navigation as a means of conducting a safe journey from one port to another.

NPS Photo/N. Howk

Ashland Harbor Breakwater Lighthouse |

Last updated: September 24, 2021