The ability to capture a moment in time has fascinated us ever since an image was first produced in 1839. First a novelty, then a powerful medium of information and emotion, photography and photojournalism came of age during the American Civil War. No other conflict had ever been recorded in such detail. Nowhere else is this truer than at Antietam, the first battlefield photographed before the dead were buried. It started with just a few, but by 1865 dozens of photographers were hauling glass plates and volatile chemicals across the war-torn countryside. Today, because of their work, we can still look into the faces of soldiers and visit the locations of tragic events. Photography Comes to America The initial problem with glass plates was keeping the light-sensitive chemicals on the glass. Archer overcame this problem by using a sticky transparent liquid called "collodion." For this new process a puddle of collodion was poured onto a glass or iron plate. Then the plate was tilted so that the collodion flowed over the entire plate leaving an even coating. When the coating began to set, the plate was then taken into the "darkroom" and then lowered into a bath of silver nitrate where it received its light-sensitive coating. The plates had to be sensitized just minutes prior to making the exposure and then developed before the coating dried - thus the name "wet plate" photography. After exposing the plate – "taking the picture" – the photographer had to quickly fix and wash the plate thoroughly. Then the finished image was dried over an alcohol lamp and coated with a varnish for protection.

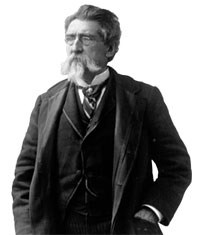

Samuel Morse, inventor of the telegraph, was in Europe and he helped bring the magic of photography to the United States. One of his students was Matthew Brady. Brady opened his photographic studio in New York City in 1844 where he became almost as famous as the notables who sat for their portraits. Brady’s gallery was still using the Daguerre silver plate process. In 1856, glass plate photography made it to the States and no one perfected its process, or used it more effectively, than Brady’s employee Alexander Gardner. Alexander Gardner at Antietam It wasn’t until September of 1862 that the first true images of war were produced. Antietam was the first battle to depict the grim and bloody truth of civil war through the lens of photographer Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson. Gardner made two trips to Antietam. The first was just two days after the battle, the second, two weeks later when President Abraham Lincoln visited the battlefield. Antietam Stereo Image and the Published Woodcut

|

Last updated: September 15, 2023