NPS/E. Leonard In only fourteen months of operation, approximately 45,000 Union prisoners of war were held in the Confederacy's Camp Sumter military prison at Andersonville. In the 150 years since the Civil War, the experiences of the men confined here continue to resonate with each succeeding generation. Documenting the lives of these prisoners, and preserving their experiences, is an important and ongoing process. This research is largely carried out by descendants of the prisoners, making Andersonville National Historic Site a unique place where visitors help tell the complex stories of what happened here. Where to Begin The first place to begin your research is at the National Prisoner of War Museum. In the lobby of the museum, park staff maintains a computer database of more than 42,000 names of men who are confirmed or possible prisoners of war at Andersonville. This database is only available in the museum lobby and is not published online. There are several older versions of our database that are online at other sites, however the staff at Andersonville does not maintain or control these. If you are unable to visit the park to search the database personally, please contact us, and a member of our staff can search the database for you. For a limited number of prisoners, the park has resource files stored in the library, that contain copies of service records, pension records, and in a few cases even copies of letters, diaries, and photographs. In the event that the park does not have a file on a soldier or only has a name in the database, visitors to Andersonville can help tell their story. Generally the next step is to begin to contact the National Archives or the appropriate state archive.

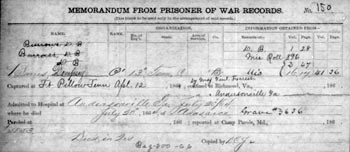

What do I need to find? In order to identify a soldier as a confirmed prisoner of war at Andersonville you will need to find the soldier's service records. These records usually consist of muster rolls, which would provide confirmation of when and where the soldier went missing. For most prisoners of war, these records may also include a "Memorandum From Prisoner of War Records," which would list the prisons that the soldier was held in. Not all Union prisoners of war were sent to Andersonville, and these records provide the best confirmation that a soldier was held at Andersonville. Another valuable source of information on former prisoners is pension records. For solders that died at Andersonville, their spouses and families were eligible for pensions. Survivors were granted pensions as well. These records often contain affidavits and statements that attest that a soldier was held at Andersonville and can sometimes even include stories from their captivity. Although valuable sources of information on soldiers, pension records are not always definitive. Because veterans could get more money if they were a prisoner at Andersonville, fraud was commonplace. As a result, pension records alone cannot provide confirmation that a soldier was held at Andersonville. Letters, diaries, memoirs, newspaper articles, and photographs are also useful in helping tell a prisoner's story. Where can I find these things? The best source of service records and pension records are the National Archives. Copies can be requested by visiting www.archives.gov. Military service records can be requested using form NATF86 and pension records can be requested using form NATF85. If the National Archives has the records you are looking for, they will charge a fee to make copies. The National Archives website has further information on these fees and services. In addition, some states maintain records of soldiers who served in Civil War. Increasingly some records are being made available online through genealogical research companies. These companies charge a fee for membership and there is no guarantee that they will have copies of the records that you are looking for. In most cases they are simply providing records held at the National Archives. The most prominent of these sites are www.ancestry.com and www.familysearch.org, which are basic genealogical research assistance sites, and www.fold3.com, which specializes in military records*. Both Ancestry and Familysearch's prisoner of war records include original hospital and burial records from Andersonville. Fold3 has digitized service and pension records for many, but not all, Union and Confederate soldiers. What do I do once I find these records? Andersonville National Historic Site uses records collected by visitors to create and maintain the database and prisoner research files. Records that the park is interested in are, in order:

If you acquire these records and would like to provide the park with copies, they can be emailed or mailed to: Andersonville National Historic Site Keep in mind that the park collects information as it relates to the prisoner of war experience. Please do not submit family trees, family histories, or documents that are unrelated to the prisoner of war experience. In addition, print outs of message board threads from genealogy websites are not considered reliable sources and are not needed for our resource files.

Hugh Peacock What does the park do with these records? Records submitted are used to update and maintain the database that is accessible in the museum lobby. Please note that the database is intended to simply be a research assistance tool, and is not intended to be a "Roll of Honor" or any other means of memorialization. The records are then placed in resource files that are housed in the research library in the National Prisoner of War Museum. Park staff and volunteers often use these records in order to develop education programs, living history portrayals, and other public programs. In addition, historians sometimes utilize these records as they conduct academic research on the history of Andersonville Prison. These records are also available to researchers conducting either academic or genealogical research. The library is open for public research by appointment only. Appointments must be made at least two weeks in advance. The library may be reserved for research Monday through Friday from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Use of the library may be limited on specific days throughout the year. Please note that the park library is closed on all Federal holidays. Bear in mind that for most genealogical research inquiries, a visit to our library is not necessary, as we do not have records on the majority of prisoners held here. For more information on scheduling a research appointment in the library, e-mail us.

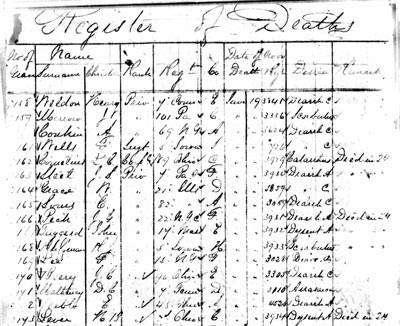

What If I Think I Found an Error Typographical errors are very common for Civil War records, and especially those from Andersonville, GA. Many errors aren't actually errors at all – rather they reflect how a name might have changed spelling over time. For example, this was especially prevalent amongst German immigrants who served in the Union army. They might have spelled their name one way, but during and after World War I the family changed the name or spelling to look or sound less German. In other cases as literacy evolved, name spellings changed as well. Just because a descendant spells a name one way does not necessarily mean that their ancestor spelled it the same way. However, there are many examples of misspellings and misidentified states throughout the limited Andersonville Prison records, especially within the Death Register. The Death Register was maintained by paroled prisoners; most famous among these was Dorence Atwater, who published the list after the war. Typically when a soldier died his friends would record his basic information on a scrap of paper that would be affixed to his body. This information was recorded in the Death Register and assigned a number that corresponded with a grave location. Due to the inconsistency of these primitive "dogtags" and the hurried nature of recording this information, many errors were made at the time. These errors were not corrected after the war and, further complicating matters; the published Death Register was then used to compile regimental rosters after the war. This led to the listing of men on regimental records who didn't exist at all. These errors of transcription, most of them dating to the time of the prison's operation, are a reflection of the history of the place and tell a story. The Civil War headstones, especially those with errors, reflect the limitations of record-keeping of the era, and the remarkable efforts over a century and a half to document and remember those who died while held in captivity here. Although it is the policy of the National Park Service not to change historic headstones, the museum database will be updated in order to reflect correct or other information, as needed.

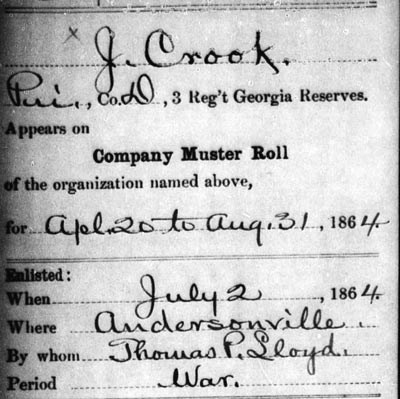

What about Confederate guards? The mission of the Andersonville National Historic Site is to tell the story of American Prisoners of War. As a result, documenting guard staffs at individual camps is not the park's highest priority. However, we are happy to assist those seeking to document the service of a Confederate soldier stationed at Andersonville. If you are conducting research on a soldier who may have been a guard the first thing to check is the soldier's unit. Just because a soldier was from the local area does not mean he was a guard. The units that served as guards were the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Georgia Reserves, and elements of the 55th Georgia and the 26th Alabama Infantry. A battery of Florida artillery was also stationed at Camp Sumter. If a soldier was not a part of one of these units, he was probably not a member of the guard force at Andersonville. The National Archives maintains limited Confederate service records, which may be accessed by contacting the National Archives directly or through www.fold3.com*. Most records from various Confederate units are maintained by their respective states. At the end of the war many states' records were lost or destroyed, so there is significant inconsistency in the availability of Confederate service records, especially among reserve and militia units. To obtain service records of Confederate soldiers you should contact the appropriate state archives and request Service & Pension records: Georgia Archives, Alabama Archives, and Florida Archives If you are able to obtain these records you may send photocopies to the park so that they may be included in our research library. Other Online Resources Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System (CWSS) is a database containing information about the men who served in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War. The CWSS is a cooperative effort between the National Park Service and several public and private partners whose goal is to increase Americans' understanding of this decisive era in American history by making information about it widely accessible. This database was intended as a starting point for people beginning their research, and is not considered a "roll of honor." As such, this database is not being updated, and Andersonville National Historic Site does not have any control over the content published in the CWSS. A List of the Union Soldiers Buried at Andersonville The Andersonville Death Register was published in the New York Tribune in 1866 by former prisoner Dorence Atwater. For many families, this was the first notification that their loved ones had died at Andersonville. This record, although imperfect, reflects how names were spelled and labeled in the original records. Atwater's list is what was used to identify the dead at Andersonville and to label the markers in the cemetery.

*The National Park Service neither sponsors nor endorses these sources. |

Last updated: July 9, 2023