The War of 1812 represented the first time in its history that America declared war on another nation. But that declaration did not indicate national consensus on the conflict. From the beginning, partisan quarrels in the legislative branch reflected deep and ominous differences of opinion over the War of 1812.

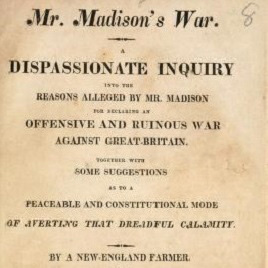

“An offensive and ruinous war.” John Lowell, an outspoken critic of the conflict

John Lowell, Mr. Madison’s War (Boston: Russell and Cutler, 1812)

As they grew increasingly frustrated by the failure of President Jefferson’s and Madison’s policies of economic sanctions to win concessions from the British, a faction of congressmen known as the War Hawks began calling for more decisive and aggressive measures.

On June 1, 1812 President James Madison sent his war message to Congress. That message outlined what he believed to be America’s chief diplomatic grievances with Britain: impressment, the British Orders in Council, and Britain’s incitement of Indian warfare on America’s western frontier.

The Constitution gives the power to declare war to Congress. No Congress had exercised that power in the country’s nearly 25-year history. But in June 1812, the House and Senate narrowly approved the measure declaring war on the British. President Madison signed the Congressional war measures into law on June 18, 1812, marking the official commencement of the hostilities.

But enthusiasm for war against Britain was hardly unanimous. The vote in the House was 79 to 49; nearly four in ten representatives voted against the measure. The vote in the Senate was even closer, with 19 senators in favor and 13 opposed. It remains the closest vote in America’s five formally-declared wars.

And the vote occurred along strictly partisan lines. All 98 of the congressmen who voted for the war were Republicans. (Even within the Republican party, support for the war was hardly unanimous: one-quarter of Republicans either voted against the measure or abstained from the vote.) Not a single Federalist voted for the war. The partisan divisions led critics to later pronounce the War of 1812 "Mr. Madison's War."

Those critics might have had a point. Madison’s principal grievances were with the British. But in defining the war’s stakes, Madison and the Republicans also had domestic and partisan interests in mind. For one, Republican leaders hoped that war would help unite their own increasingly divided party, unity they calculated as vital to keeping the Federalists in check. Republicans hoped that by unifying the country, war would silence Federalist opposition once and for all silence.

As it turned out, the war did more to inflame than tame the Federalists. Party members grew increasingly strident in voicing their dissent against Madison and the Republicans for declaring what they viewed as an “offensive and ruinous war against Great Britain.”

Last updated: May 24, 2016