Last updated: April 5, 2021

Place

Yukon Island Main Site National Historic Landmark

Frederica de Laguna, 1934

Yukon Island (Ni'ka)

About a mile wide and over a mile long, Yukon Island is easily the largest island in Kachemak Bay. The island has its own springs and small streams, and is forested with Sitka spruce and hemlock, while grasses and willow grow in low-lying areas. The island is called Ni'ka or Ni'qa ('big island') by local Athabascan. The position of Yukon Island at the outlet of Kachemak Bay is an important aspect of its story. From here, you can oversee the passage in and out of Kachemak Bay, controlling access to the bay’s wealth of resources. Kachemak Bay and the Gulf of Alaska region are an intersection where Athabascan, Yupik, and Aleut territories overlap.

Kachemak Bay is a National Estuarine Research Reserve, on the south side of Kenai Peninsula. The picturesque bay is 40 miles long, rich in fish, shellfish, kelps, many sea birds, and sea mammals like whales, sea otters, porpoises, and seals. There is also moose, bears, coyotes, and smaller mammals on land. In the past, caribou herds moved through the area. The shoreline is mostly rocky, with dramatic sea cliffs and a few small islands are scattered close to the mainland shore. From Kachemak Bay, the Kenai Mountains and its ice fields are visible to the east, and volcanoes on the Alaska Peninsula can be seen across the Cook Inlet to the west.

Today, the Kachemak Bay towns of Homer and Seldovia are popular vacation destinations.

People have been living here for over 4,500 years...

The Yukon Island Main Site National Historic Landmark and Yukon Island Archeological District is made up of archeological sites that preserve the history of the bay. Archeology in Kachemak Bay represents much of the span of human history in the Gulf of Alaska and the Kenai Peninsula.

Sites as old as 9,000 years have been found elsewhere in the Gulf, like those at Amalik Bay Archaeological District National Historic Landmark. So far, Kachemak Bay sites have been found to extend back from about 2500 BC (4,500 years ago) to the more recent past. Artifacts found here encompass different archaeological periods. The technology that defines each period was developed outside of Kachemak Bay before being brought to the area.

The earliest known settlers of Kachemak Bay are of the Ocean Bay archaeological tradition- a technology that’s distinctive in style, manufacture, and period. They left behind the 4,500 year old artifacts in the area. Remnants of the Arctic Small Tool tradition show that they used the bay, too, around 2000 BC (4,000 year ago). The archeological period most studied in the area is known as the Kachemak tradition, which came to the area around 1000 BC (3,000 years ago) then stopped using the bay about 500 AD (1,500 years ago). After 500 AD, archeological evidence confirms the continuous use of the area by Athabascan and Alutiiq groups since.

Archeology of the Yukon Island Archeological District

House remains in the Landmark are a semi-subterranean style, meaning they were constructed with foundations that were dug into the ground rather than built on the ground surface. The upper portion of homes were made of wood and covered in sod. On Yukon Island the ancient sites are the Yukon Island Main Site National Historic Landmark (a village), the Fox Farm site (a seasonal camping spot), the Bluff site (another village), three other sites where inhabitants left heaps of shells and other artifacts, a small cluster of houses, and finally, a wartime refuge site.

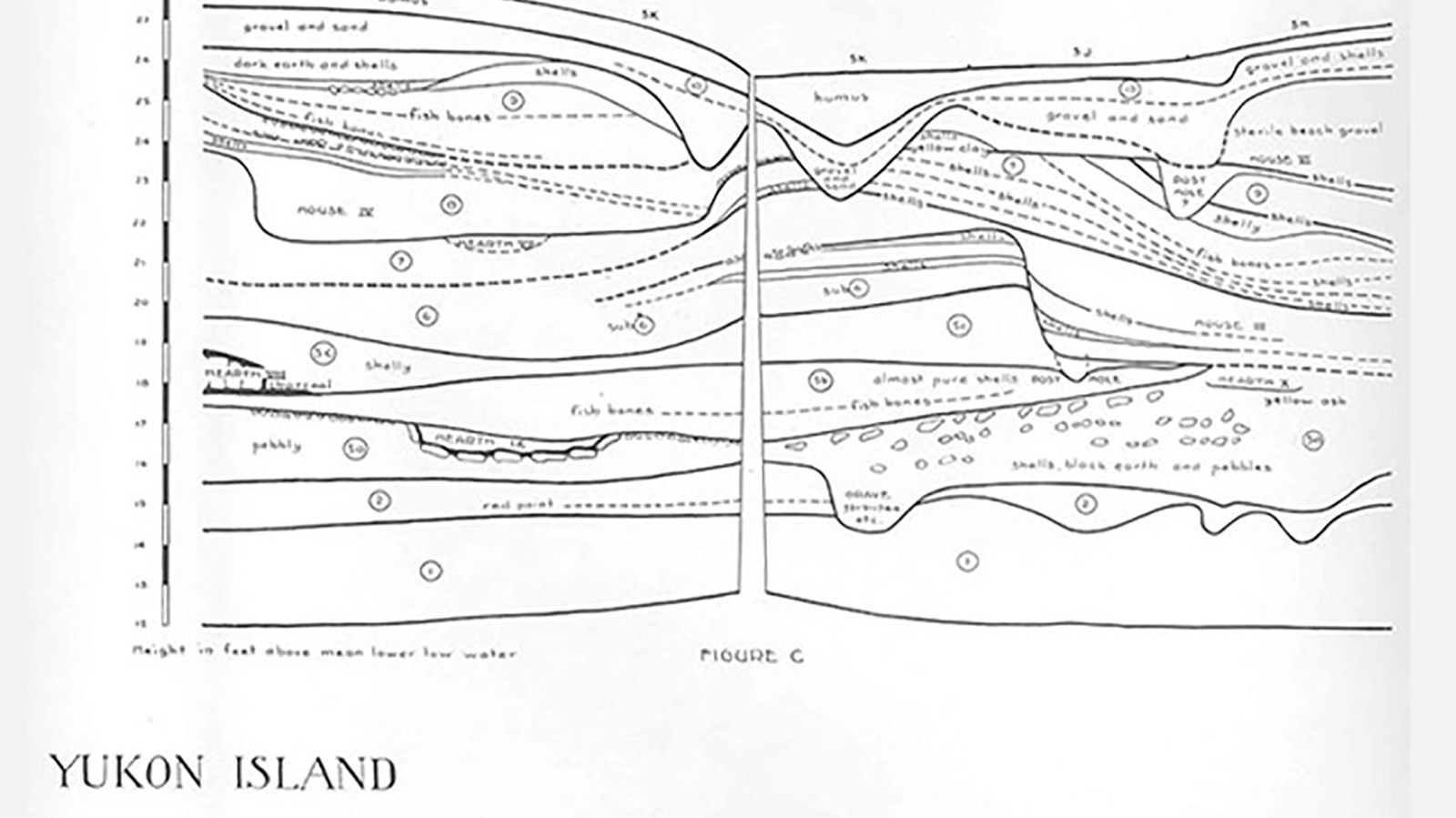

Almost the entire length of the Kachemak tradition period and some Athabascan culture is represented at these important sites. The depth of the archeological deposits, up to 12 feet deep, reflect the millennia that Alaskans have lived on Yukon Island and enjoyed the natural wealth of Kachemak Bay.

The Yukon Island Main site is a village with homes, shell and refuse piles, and burials in an area where the beach is sheltered from poor weather.

The Fox Farm site was used as a seasonal hunting and fishing camp by Late Kachemak people and later, Athabascan.

At the Bluff site is a small Late Kachemak village that has the advantage of an upland view of the ocean. People stayed here to hunt seals and porpoises.

On a high and narrow point of land, the Refuge site is the most fitting spot on the island to keep lookout and have a strategic advantage over invaders. Here, archeologists have recorded the remains of ancient houses and a shell heap.

During the shudder and sway of the 1964 Good Friday earthquake, parts of Yukon Island's archeological sites subsided (sunk) below sea level. Some of the sites remain under a consistent threat of erosion.

The Kachemak tradition and Yukon Island were first studied by Dr. Frederica de Laguna, the first woman anthropologist and archeologist to dedicate her career to Alaskan heritage. Dr. de Laguna found the Yukon Island sites on her first expedition to Alaska in 1930, bringing her brother Wallace as her only assistant and as a bear guard. Artifacts from the Yukon Island Main site were used by Dr. de Laguna to define the Kachemak archeological tool tradition. She wrote the Archaeology of Cook Inlet, Alaska (1934), the first modern monograph on Alaska culture and history about an area little understood by outsiders. Since then, we now know that the Kachemak tradition was practiced in the Kodiak Archipelago and at Amalik Bay Archeological District National Historic Landmark (Katmai National Park & Preserve).

The Kachemak tradition: life is art and ingenuity

The Kachemak tradition was unknown to archeologists before being found at the Yukon Island Main Site in the 1930s. The site is a seasonal village made up of semi-subterranean houses and deep middens filled with animal bones, shell, and broken tools. The Kachemak tradition turned out to be one of the longest lasting and most significant archeological periods in the Gulf of Alaska region. Kachemak tool users lived on Yukon Island between 1000 BC and 500 AD.

It was during this period that cultures in the gulf region began to converge on harvesting more and more fish. Through examining artifacts archaeologists define two main Kachemak periods, Early Kachemak and Late Kachemak. Early in the Kachemak period, around 1000 BC, residents began shifting focus from sea and land mammals to harvesting large amounts of fish and probably storing them for use through the rest of the year. First lots of sea fish, like Pacific cod, halibut, and herring. While in Kachemak Bay, they also targeted seals and porpoises. By the Late Kachemak, they had moved on to develop an exceptional salmon industry.

Another amazing characteristic of the Kachemak tradition is the progress of artistic expression during its time. Many works of art and personal adornment were preserved at archeological sites and in graves. These include hundreds of bone and shell beads from clothing and jewelry, labrets (lip jewelry), carved-shell eyes, elaborate masks and other carvings, and stylized bone knives. The variety of graves and their goods during this period convey a complex society of differing social or economic classes.

It is currently unknown to researchers why the Kachemak tradition abandoned Kachemak Bay around 500 AD. Archeologists speculate that some combination of overexploitation of seals, the scarcity of salmon in the bay, violent conflict over resources, or forces of nature prompted a migration out of the area.

In the Gulf of Alaska, the end of the Kachemak period is marked by a cultural transition (sometime around 1200 AD) into the Alaska Native groups that would be some of the first to encounter European prospectors in the late 1700s. While they had then, and now, a prosperous salmon enterprise, it was a broad economy that included everything available from the wealth of the natural landscape and trade with people beyond the gulf. These groups still thrive in Alaska today.

Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) and Athabascan (Dena'ina) descendents

When Russian ships arrived in the Gulf of Alaska, the southern coast of Kachemak Bay was occupied by Alutiiq (Sugpiaq/Sugpiat) and the northern shore by Athabascan (Dena'ina).

Alutiiq and Dena’ina in Alaska maintain and celebrate their traditions today through the arts of storytelling, music and dance, local cuisine, and expertise in art and craftsmanship.

The Alutiit and their traditions are an important part of the community on Kodiak Island. They are masters of the art of building custom skin boats for sea mammal hunting. In the past they hunted in skilled fleets of kayaks for seals, porpoise, and even whales.

Athabascan of Kachemak Bay are unique to their broader culture and language group because of their ocean traditions. Athabascan in Alaska are part of a large language group that extends from central Alaska to central Canada, and are also in the western plains of the United States (Apachean). Most rely on inland plants, animals, and freshwater fish. While only a few, like Dena’ina Athabascan coastal communities in southcentral Alaska and the Alaska Peninsula, incorporate some ocean resources in their cultural traditions, even today.

Additional Information

Archaeology of Cook Inlet, Alaska

By Frederica de Laguna. The Alaska Historical Society, 2nd edition, 1975.

The Early Kachemak Phase on Kodiak Island at Old Kiavak

By Donald W. Clark. Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1997.

Expanding the Kachemak: Surplus Production and the Development of Multi-Season Storage in Alaska’s Kodiak Archepelago

By Amy F. Steffian, Patrick G. Saltonstall, and Robert E. Kopperl, Arctic Anthropology, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2006.

Recent Archeological Work in Kachemak Bay, Gulf of Alaska.

By William B. Workman, John E. Lobdell and Karen Wood Workman, Arctic, Vol. 33, No. 3, 1980.

Yukon Island Bluff Site (SEL-041): a New Manifestation of Late Kachemak Bay Prehistory.

By William B. Workman and John E. Lobdell, Alaska Anthropological Association 6th annual meeting, 1979.