Person

Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelmine_Kekelaokalaninui_Widemann_Dowsett#/media/)

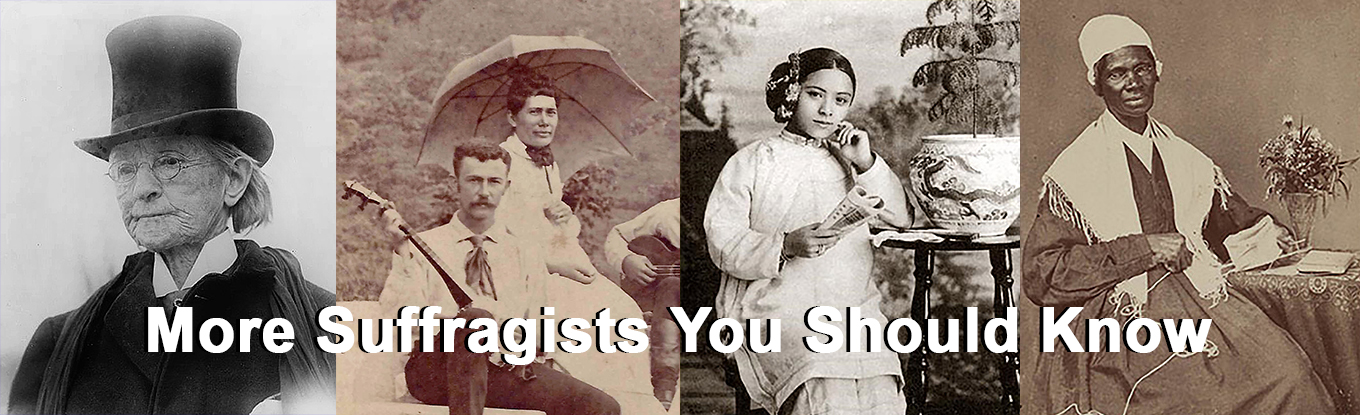

Born in 1861 at Lihue, Kauai in the Kingdom of Hawaii, Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui Widemann was the daughter of Mary Kaumana Pilahiulani, a Native Hawaiian, and German immigrant Hermann A. Widemann. Part of the Royal Hawaiian family, her father was a cabinet minister for Queen Lili’uokalani. Due to these connections, King Kalākaua and Queen Kapi’olan were present at her wedding to Jack Dowsett in 1888.

Five short years later, pro-American interests, with the assistance of US Marines, overthrew Queen Lili’uokalani and established the Republic of Hawai’i. The former island nation was annexed to the United States in 1898. With the introduction of this new territory to the Union, the mainland suffragists turned their eyes towards the Pacific to see if any progress could be made.

Written by Susan B. Anthony and other officers of the NAWSA, the “Hawaiian Appeal” of 1899 asked the US Congress to give Hawaiian women the right to vote “upon whatever conditions and qualifications the right of suffrage is granted to Hawaiian men.” While Anthony and others wanted all women to have voting rights, they were especially concerned about non-Christian Native Hawaiian men gaining that power before the white and Native Hawaiian women of the territory. The Hawaiian Appeal received criticism from almost all corners. Local women, like Dowsett, felt that petitioning the territorial government for greater civil rights was the way to go.

In 1912, Dowsett founded the National Women’s Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai’i (WESAH), the first Hawaiian suffrage organization. Modeling its constitution on that of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), they invited mainland suffragists to speak to the group. One of these women included Carrie Chapman Catt in 1918, who spoke in positive terms about the group after the meeting.

Thanks to the efforts of women like Dowsett and WESAH, President Wilson signed a bill allowing the residents of the territory to decide for themselves. Gathering both Native Hawaiian and white suffragists at the capitol building on the morning of the Senate vote on March 4, 1919, Dowsett declared:

“Sister Hawaiians, our foreign sisters are with us. Senator Wise asked us yesterday if the so-called ‘society women’ were leading us, and we told him that this was not so. We are working all together, and we want the legislature to know this. And we must also remember our Oriental sisters, who are not here today but who will also unite this great cause.”’

While many in the territory, like those on the mainland, were against granting the right of suffrage to Asian women, Dowsett included them in her vision of Hawai’i’s future. The bill passed the Hawaiian Senate that day, but a fresh battle was waiting in the House. Instead of granting women’s suffrage immediately, the House decided to put it to a vote of the Hawaiian electorate in 1920. Furious with that response, Dowsett and 500 other women of “various nationalities, of all ages” poured onto the House floor with banners demanding “Votes for Women.” Forced to reckon with the demonstrators, the House held hearings the next day for proponents and opponents to make their case. Standing alongside Dowsett were a wide variety of Hawai’ian women including Princess Kalaniana’ole and Lahilahi Webb, former lady-in-waiting to Queen Lili’uokalani’s court.

A month later, the House had not budged and the suffragists of Hawai’i were losing their patience. Regrouping, Dowsett and her group began to lobby directly to the U.S. Congress through the territorial representative, Prince Kūhiō. They also began to create grassroots groups throughout the territory to prepare women for the vote when that opportunity arrived. Hawaiian women became enfranchised along with their mainland sisters when the 19th Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution in August 1920. As residents of a U.S. territory, however, their elected representation was limited.

It would take another 39 years for Hawai’i to become the 50th state in the Union, and for the residents of Hawai’i, both male and female, to gain full US voting rights. Dowsett did not live long enough to see that day; she died December 10, 1929. She is buried next to her husband in Oahu Cemetery, Honolulu.

Bibliography

Barker, Joanne. Indigenous Feminisms. The Oxford Handbook of Indigenous People's Politics, edited by Jose Antonio Lucero, Dale Turner, and Donna Lee VanCott. Oxford University Press, published online 2015.

Choy, Catherine Ceniza, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu. Gendering the Trans- Pacific World. Brill, 2017.

“Hawaii.” US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/APA/Historical-Essays/Exclusion-and-Empire/Hawaii/

“Hawaiian Women Join with Haoles to Work for Vote.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 5 Mar. 1919.

Sneider, Allison L. Suffragists in an Imperial Age US Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870-1929. Oxford University Press, 2008.