|

Women's Rights

Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER ONE:

HISTORIC SETTING — SENECA FALLS IN 1848

To comprehend the significance of the 1848 Women's Rights Convention, it is necessary to understand the milieu in which it occurred. The event was not an aberration, but the natural outgrowth of local conditions and concerns. In 1848, Seneca Falls was in the midst of a major social and economic change. From the small agricultural processing center it had once been, it was becoming a bustling manufacturing center, inundated with new ideas, new businesses, and new people. The old vision of slow moving canal boats loaded with barrels of locally produced flour was being rapidly replaced by the sight of pumps, tools, and machinery speeding from the area by train. Accompanying this economic acceleration had been the usual influx of new populations and novel ways of thinking. Elizabeth Cady Stanton's call for women's rights was as much a response to local conditions as it was a personal conviction.

A. Transportation Systems

Seneca Falls' fortuitous location at the hub of several important transportation arteries has played a major role in its growth and development. The first white settler in the area, Job Smith, stayed in the Flats because he saw a living for himself in the business of portaging settlers and their goods around the mile long series of rapids on the Seneca River. He arrived in the area in 1787, just in time to take advantage of the sizeable westward migration then passing through New York State. [1]

In 1782, the state legislature had designated some 1,680,000 acres of territory in western New York as bounty land for veterans of the Revolutionary War. The area, known as the Military Tract, was comprised of the present day counties of Cortland, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and parts of Oswego, Wayne and Tompkins. [2] For the next 50 years, thousands of settlers streamed through this territory along the natural pathways of the rivers and lakes. In the early years, most of these pioneers were from the New England states and followed the Mohawk Valley trail out to the western lands. Later, New Jersey and Pennsylvania natives entered the territory along the Hudson and Susquehanna Rivers. [3]

Wishing to encourage and facilitate this migration, the State of New York appointed a commission in 1794 to lay out a road "as straight as possible" to run from Fort Schuyler on the Mohawk River to Canawagas on the Genesee. [4] As surveyed, the Great Western Road crossed the Seneca River near the Seneca Falls rapids and continued westward on the northern side. As expected, settlements and way-stations began to appear everywhere along the highway's route, as people prepared to profit by selling goods and services to the many travellers who would soon be wending their way westward. The land agent in Geneva paid tribute to the enterprising spirit of the early New Yorkers by reporting that "The line of road having been established by law, not less than fifty families settled on it in the space of four months after it was opened. It now bides fair to be, in a few years, one continuous settlement from Ft. Schuyler to the Genesee River." [5]

Seneca Falls was no exception to this observation, and the earliest village properties sprang up along the turnpike's route, present day Seneca and Fall Streets. The south side of the river was virtually ignored as tavern and shop keepers concentrated on lining the highway on the northern side. Other settlers in the area made their living through the "carrying trade," transporting the still heavy river traffic around the rapids, or ferrying people across the upper end of Cayuga Lake so they could avoid the stretch of road which passed through the difficult Montezuma Swamp. Nearly all of the pre-1825 settlers in Seneca Falls earned their living by catering to the heavy volume of traffic which passed along the road.

As the migration continued without abatement through the early decades of the 19th century, further improvements were made along the highway. In 1800, the first of three bridges was constructed across Cayuga Lake, replacing the old ferry run. Built at the enormous cost of $150,000, the bridge was more than a mile long and said to be the longest in the world. It was also said to have the highest toll in the world, at 25¢ for a man and horse, and proportionally higher fees for vehicles and freight. This first bridge lasted only seven years before its mud sills collapsed and the ferry service had to be resumed. A new pile bridge was constructed in 1813, but it too fell prey to the lake and the weather and had to be replaced. [6] The third and last bridge was abandoned in the 1850s and was never rebuilt as the railroad and new highways had by then superceded the old turnpike as the primary means of travel across the state. [7]

Another improvement on the highway was the establishment of the Seneca Road Company in 1800 whose purpose was to improve and maintain the state road from Utica to Canadaigua in return for the right to collect fees. Tollhouses were established every 10 miles along the route, and the portion of the road which passed through Seneca Falls came to be known as the Seneca Turnpike. It served as the main east-west artery across the state and the gateway to the northwest territories for well over a hundred years. People, ideas, and products flowed through Seneca Falls in a nearly constant stream. A regular coach service was soon instituted, and later, early residents remembered how the twice weekly mail coach would sound its horn at the corner of Seneca and Washington Streets just below the Stanton House before crossing the bridge into town.

As farmers and businessmen began to settle in the area, they began searching for an easy, economical way to transport their surplus products to eastern markets. The heavy tolls on the turnpike made that option unreasonable, but the many rapids on the Seneca River made water transport equally difficult. Hoping quite literally to get around the problem the Bayard Company, owners of most of Seneca Falls' valuable real estate, formed the Seneca Lock Navigation Company in 1813. Their intention was to build a series of locks to open navigation between Cayuga and Seneca Lakes so as to do away with the laborious portage around the Seneca Falls rapids, which was a serious economic drain on their operations. Between 1801-1806 the pilots at the portage point had taken in nearly $1,500, nearly all of it from portaging products from the Bayard Company's two mills which held a virtual monopoly on processing and exporting local grain products. Although they had the best of economic reasons for wishing to build the canal, the company fell short of the requisite cash, and work on the Seneca-Cayuga Canal lagged until the state stepped in with an additional $21,000 grant. In 1817, the first canal boat came through the locks, providing Seneca Falls with yet another link in its transportation network. [8]

Although the early canal provided an important transportation route, both in and out of the Finger Lakes region, it was not until 1828 that the canal reached its full potential. In that year, the state took over responsibility for the waterway, and proceeded to link it with the great Erie Canal system at Montezuma. Andrew Tillman, a local businessman, was awarded the contract for the canal improvement. Under his direction the locks were rebuilt, the channel widened, and the first towpath added. [9] Seneca Falls now had an inexpensive direct outlet to all of the eastern markets, and incoming settlers had a convenient water route from the coastal cities.

The modernization of the Seneca-Cayuga Canal and the concomitant freeing of the village water rights by the liquidation of the Bayard Company, had an enormous impact on the settlement. The 1830s were a period of enormous growth for the village, particularly along the south side of the river. Dozens of new mills appeared along the waterfront, hundreds of new residents joined the town, and an energetic boat-building industry appeared. The primary commercial activities in the village at this time included the processing of local agricultural products (milling, tanning, distilling), boat building, coopering, and canal tending. All of the major economic activity depended directly or indirectly on the canal. The annual toll figures for several years show the phenomenal increase in the number of goods being shipped in and out of the area.

1829 — $ 8,643.49

1833 — $ 18,130.43

1841 — $ 23,583.37 [10]

Passenger traffic also greatly increased with the introduction of packet boat service in 1828. It brought regular transportation service, comfort, and excitement to the town. One early resident recalled that before their introduction "our village was indifferently connected with the outside world . . . the packet wrought a decided improvement, brought us in close touch with other communities and converted us into a canal town with something of cosmopolitan features." [11] Demand for the packet service was so great that at one time, two rival companies competed for business with raucous brass bands, fancy uniforms, and free rides, all to the great delight of the village residents. [12] It was on one of these packets that Thomas McClintock and his family travelled from Philadelphia to Waterloo in 1835-1836.

On July 4, 1841, the first Auburn-Rochester train arrived in Seneca Falls and foretold the demise of the canal. The Seneca Falls Democrat reported that on the historic occasion, "The Cars were filled to over flowing: and their approach to this village was announced by the roaring of cannon, and the shouts of a vast multitude of citizens and strangers, who had collected in the neighborhood of the depot to welcome 'the steam horse' and his load." [13] The coming of the railroad had a great impact on the village, as it did for all the settlements along its route. No longer did one have to wait for the lumbering stagecoach to bring mail over the turnpike, it could now be whisked away by rail Passengers and goods could now be in Buffalo or Albany in a matter of days rather than a week or more. News, people, and products began to travel faster and more efficiently, linking the small rural village to the outer world. Amelia Bloomer's The Lily owed much of its success to the railroad which allowed it to be quickly distributed across the state and the nation. Without that outlet, it would necessarily have remained a local, village journal.

The railroad also made possible the extensive trips made by the many reform lecturers and organizers. While speakers had previously made the circuit by coach and horse, the railroad vastly increased their mobility and availability. Elizabeth Cady Stanton's letters are full of references to meeting friends and sympathizers at the rail depot in Seneca Falls. We know for instance that the Motts and Martha Wright arrived at the Convention by train, as presumably did many others. Lucretia Mott wrote to Stanton a few days before the gathering, "We shall go from the Cars directly to the Meeting . . . . Give Thyself no trouble about meeting us." [14] The train made it possible for news of the convention to be quickly spread across the area, as well as bringing participants to the gathering itself.

In addition to facilitating the movement of people and ideas, the train made it possible for local manufacturers to have national markets for their goods. It was at precisely the same time that the railroad first arrived in town, that Seneca Fall's industrialists began to shift from a processing oriented economy to one dependent on heavy manufacturing. In the early 1840s, the tide of migration through New York began to slow, and the major grain producing area shifted westward to Ohio, Illinois, and Iowa. No longer were farmers bringing in wagonloads of wheat to be processed in the village mills and then shipped to local markets by canal boat. As the demand for milling decreased, so did the dependent trades of coopering and boatbuilding.

Seeking new economic opportunities, the various mill owners began diversifying and shifted their operations over to manufacturing. Abel Downs led the way with the establishment of the first pump factory in 1840, and others soon followed suit. Such an industry would not have been possible 10 years earlier. The local market would soon have been glutted with pumps, with no system for transporting the surplus elsewhere. It was only with the coming of the railroad and a nationwide system of rapid transport that such industries could become viable concerns. The local pump and manufacturing industries were also fortunate in that their rise coincided with the opening of the western prairies, creating a huge market for their various pumps, plows, and tools.

One by-product of the railroad was the revitalization of the business district on the north side of the river. Although it was the oldest part of town, it had been overshadowed by the south side during the 1830s when that area had been heavily developed by Ansel Bascom, Andrew Tillman, and Gary V. Sackett in conjunction with the improvements on the Seneca-Cayuga Canal. The location of the new railroad depot on the north side of the river shifted the transport and passenger emphasis from the canal on the south side to the railroad on the north side.

Although the coach, canal, and turnpike continued to be used in Seneca Falls throughout the 1840s and 1850s, the days of their supremacy were definitely over by 1845. The village inhabitants were now connected to the larger world by a more rapid and efficent means of transportation, and they were eager to embrace it. The 1840s and 1850s witnessed a period of great energy and experimentation as Seneca Falls attempted to analyze and utilize the new opportunities and problems presented by the railroad.

B. Industry, Commerce, and Labor

The 19th century industrial development of Seneca Falls divides itself easily into three distinct phases: 1787-1826, a frontier economy based on trade and mill center with regional markets; 1825-1850, a developing trade and mill center with regional markets; and 1850-1890, a thriving industrial and manufacturing town with national and international markets. As can be seen, the Women's Rights Convention occurred during the transitional period when Seneca Falls was transforming itself from a rural mill village to a booming industrial center. The stresses, energies, and opportunities which attended this shift all played a part in the emergence of the women's right movement.

The first white settlement of the area around Seneca Falls occurred in the 1780s when families began establishing themselves at the Seneca River rapids, hoping to make a living by portaging travellers and their goods around the mile long stretch of rough water. Business was fairly good as more and more settlers began moving westward to claim land in the newly opened Military Tract of western New York. From the first day of its settlement, Seneca Falls' economic development would be intimately connected with the water power available along the shore of the Seneca River.

An energetic surveyor named Elkanah Watson first recognized the potential of the area when he visited it in 1791. He quickly began acquiring the title to land lying adjacent to the river, and a few years later formed a company with three friends to raise the necessary capital to develop it. Through a series of shady transactions, political favors, and outright purchase, the Bayard Company managed to procure the sole right to all of the water power along the rapids, and eventually owned nearly 1500 acres on both sides of the river. In 1795, Wielhelmus Mynderse arrived in Seneca Falls to act as the agent for the company and proceeded to erect several mills on the rapids, the first of many which would later line its banks.

Though extravagant in the amount of land it owned, the Bayard Company was extremely conservative in its management. Adamant about maintaining their monopoly of the milling rights in the area, they refused to lease any of their property for other operations. Population growth in Seneca Falls fell far behind that of neighboring settlements, as the only livelihood available other than farming was tavern keeping, portaging, or coopering for the mills. Mynderse later established a saw mill, a fulling mill, a blacksmith shop, and a tannery, but any profits these concerns generated went directly into the Bayard Company coffers. All of these operations were centered around processing the raw materials brought to the mills by the neighboring farmers (grain wool, hides, wood), and then distributing them to a local market. This short sighted reliance on one type of activity soon spelled the doom of the Bayard Company.

With the opening of the first Seneca-Cayuga Canal in 1817, neighboring settlements along the river began to establish mills of their own. Mynderse's two Red Mills began to lose business as customers took their grain to cheaper and more convenient mills at Waterloo and The Kingdom. While other villages began experiencing a minor economic boom, Seneca Falls stagnated. A comparison of figures between Waterloo and Seneca Falls for 1824 tell the story:

| Seneca Falls | Waterloo | |

| houses | 40 | 80 |

| stores | 3 | 7 |

| inn (taverns) | 2 | 6 |

| inhabitants | 200 | 500 [15] |

Finally bowing to the inevitable, the Bayard Company cut their losses in 1826, and divided up the property among the three remaining stockholders who immediately sold most of it to local entrepreneurs who had been eagerly awaiting the demise of the monopolistic company. Mills, factories, homes, and businesses sprang up with astonishing rapidity, and until the depression of 1837 slowed progress, Seneca Falls enjoyed a major burst of growth and economic activity. The riverfront was soon lined with mills, distilleries, tanneries, and factories. Within only seven years, the population grew from 200 to 2000, and the number of manufacturers had increased from five to more than 25. The newspaper reporting this information in 1832, assured its possibly skeptical readers that for "those who have not known the village for four or five years, the above statement may appear extravagant, but it is strictly true." [16] In keeping with its newfound status, the village was incorporated in 1831 with Ansel Bascom as its first President. Schools, churches, newspapers, and meeting halls began to appear as the village matured. (See Appendix A.)

A detailed recital of all the businesses established, renovated, merged, or failed during this period is much too complex for a report of this nature, but generally speaking, flour milling continued to be the major type of activity. In 1845, the nine mills then in operation produced a total of 2000 barrels of flour each day. [17] Textile mills also emerged as a successful enterprise, as did small factories producing paper, window sashes, carriages, and tools. The reason that the town was able to diversify so quickly from the simple processing plants of the Bayard Company was due largely to the Seneca-Cayuga Canal.

Although the canal had been in operation since 1817, it was poorly constructed and rapidly fell into disrepair. In 1828, however, the state purchased the canal from its private company and proceeded to renovate it and link it with the Erie Canal system. This opportune involvement by the state gave Seneca Falls the outlet it needed for its products, and contributed greatly to the economic growth of the village. The improvements of the canal also spawned a vigorous boat building industry in the village which peaked around 1840. Fortuitously situated along the major highways of the canal and the turnpike, and the natural advantage of the falls, Seneca Falls quickly became a thriving market and manufacturing center.

Instrumental in orchestrating Seneca Falls' new prosperity was a small energetic band of local entrepreneurs. In contrast to the methods of the absentee stockholders of the Bayard Company, these men lived in the village and did everything in their power to facilitate and encourage its economic and social growth. They served on every civic board imaginable, supported every public improvement, and served as the unofficial village elite. Such individuals included Ansel Bascom, Gary V. Sackett, Andrew Tillman, the Metcalfs, the Lathams, and the Bayards. Many of these and other prominent village figures were connected to Elizabeth Cady Stanton by either ties of marriage or friendship. Their support and high standing in the community helped lend legitimacy to the Convention in which several of them participated.

The most obvious economic contribution of these town boosters was the development of the south side of the river during the 1830s. When the Bayard Company liquidated its holdings, Bascom, Tillman, and Sackett each purchased large pieces of property on the south side. After reserving portions for their own use, they subdivided the remainder into commercial and residential lots and offered them for sale. Prior to this point, there had been almost no development at all on the south side. An early resident described it in 1828 as limited to farming with only "an old Log House and Frame Barn." [18] During the next decade it experienced an explosion of growth and rivaled the northern side of town for commercial prominence until the coming of the railroad in 1841 once again shifted attention to the north side of the river.

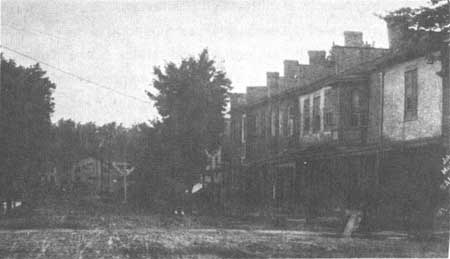

James Sanderson, who moved to Seneca Falls as a boy in 1829, recalled that Sackett and Bascom had a healthy rivalry going to see who could do the most toward developing the south side of the river. "They both had high ideals and both were going to make their own locality the business center for the north end of the county—Mr. Bascom at the south end of the Ovid street bridge and Judge Sackett at the south end of the Bridge street bridge." [19] Their competition was all to the gain of Seneca Falls, for Bascom built Union Hall and the three-story American Hotel on the corner of Bayard and Ovid, while Sackett commissioned an L-shaped block of commercial buildings and the Franklin Hotel on the corner of Bayard and Bridge (the last two developments are still standing). (See Illustration 1.) These substantial structures did much to draw people and investments across the river. Union Hall was described as "the center of village life," [20] hosting everything from temperance lectures to firemen's balls, gospel revivals to wax work exhibits. [21] Amelia and Dexter Bloomer were given a gala reception here in 1853 before their departure from Seneca Falls. Sackett's commercial block was described as "the first row of buildings in the village" [22] and the principal mercantile center of the town, containing dry goods stores, a druggist, and a hardware store among others.

|

| Illustration 1. Undated 19th century view of the Sackett Commercial Block on the corner of Bayard and Bridge Streets. Photograph taken from Revivalism, Social Conscience and Community in the Burned-Over District, Altschuler and Saltzgaber. Original at the Seneca Falls Historical Society. |

Beginning in the 1840s the town began a noticeable shift toward the mercantile-manfacturing emphasis that characterized it in the late 19th century. As the major grain producing areas moved westward toward Ohio and Illinois, the Seneca Falls millers found there were fewer farmers bringing their grain to be ground. The owners began selling the mills or renovating them to serve as small furnaces and manufacturies. A great flurry of activity was occurring along the waterfront in the 1840s as the old traditional businesses went under and new ones took their place. With the coming of the railroad in 1841, manufacturers could produce goods for a national market and not have to rely solely on the local or regional demand. A new breed of industrialists entered the village scene, quite different from the somewhat paternalistic group of early developers. Interested in tapping the new markets open to them, industrialists in the 1840s established such concerns as Down's Pumps, Cowing's fire engine factory, and Washburn Race's stove regulator business. This trend toward industrialization continued unabated in the next few decades, producing in the end, a vigorous, manufacturing oriented economy for the village. In the 1840s and early 1850s though, this process was just beginning, and the changes it brought to the commercial activity, lifestyle, and population of the village help to explain the unsettled conditions which produced the first Women's Rights Convention. (See Appendix H and Appendix L.)

One of the first indicators of this switch from a milling to a manufacturing economy was the introduction of cash payments for goods and services instead of the previous barter system. As the agricultural activity in the area began to taper and more and more people made their living through commerce or industry, the barter system became uneconomical and impractical. Previous to the 1840s, nearly all commercial activity in the area had been on a trade system. Money was scarce, and farm products always in demand. James Sanderson described how in the late 1820s the local farmers would come into Hoskins' store on Fall Street and exchange their produce for shoes or medicine:

The country customers from far and near would come and rummage over the piles of shoe leather and rattle around among the tinware, have a smoke in the meantime, sit round in everybody's way, and go home at night, having had a nice visit, disposing of their eggs at six cents a dozen and their butter at 12-1/2 cents per pound, with their pay in what they ransacked the store for. [23]

By 1848, many businesses were beginning to insist on cash payments for their products. As town dwellers and eager capitalists, they had no need for extra eggs and butter. Traditionally minded concerns like S.S. Gould's might reassure their customers in their newspaper ads that they were "always glad to exchange for Butter, Eggs, Cheese, Pork, Poultry, Dried Fruits, Fethers [sic] Good Paper or Gold dust," [24] but new businesses like the "Empire Cash Store" made no apologies for accepting cash only.

The new factories also began to institute cash wages for their employees. Prior to this time, many of the mill owners had paid their help partly in currency and partly in goods from the mill. Workers at Richard Hunt's Woolen Mill in Waterloo received only half their wages in cash, the remainder in bolts of broadcloth. [25] A young Welshman who worked in a similar mill in Skaneateles from 1848-1854, was very unhappy with this non-cash system, and described his six years in the mill as

the dullest period of my whole life. The daily schedule of labor began at five o'clock; breakfast at six-thirty, work again from seven o'clock until twelve noon; begin again at one o'clock and leave off for the day at six-thirty p.m., making a total of seventy-two hours a week." [26]

Hoping to get ahead in the world, young Bailey travelled to Seneca Falls and secured employment in one of the many factories there. Here, too, employees were not paid in cash. His reaction to this situation was typical of the new breed of mill hand appearing in the mid-19th century.

No cash payments were made to the employees of the . . . firm. There were no pay days; the men were given script orders which were accepted at all the stores and boarding houses in payment for all necessaries at a discount of from 2% to 15% according to the urgency of the needs of the holder. I endured this treatment for about eleven months. I then secured a position in the works of Cowing and Co., the firm consisting of John P. Cowing and John A. Rumsey. This firm paid their help in currency, monthly. As a machinist, I looked upon pump work as a little below me, but the cash payments did away with these notions." [27]

Bailey's unwillingness to accept the paternalistic script system which effectively tied him to one factory and one town, was symptomatic of the changes in the laboring class at this time. Mill hands were no longer the sons of local farmers helping a family friend run a small milling operation. Most were now strangers, foreign-born as often as not, with no traditional ties to a particular locale. Many were highly motivated and ambitious, working to save enough money to set themselves up in businesses of their own. Cowing's new firm with its cash wages was infinitely more attractive than the traditional, restrictive script system.

Like Bailey, many other individuals were attracted to Seneca Falls by the opportunities available in its burgeoning mills and factories. In the 18 years between 1824 and 1842, the village's population grew from 200 to 4,000, and the number of houses increased from 40 to 400. [28] We do not as yet have any definite statistics on who these new residents were, but hopefully careful study of town and census records will help us to learn who exactly was keeping all of the villages' many factories in day-to-day operation.

Scattered references in available letters and documents indicate that this mid-century influx of newcomers was heavily Irish. This would certainly coincide with the documented pattern in other upstate villages. After the Irish Potato Famine of 1847, millions of Irish migrated to America, with a large proportion ultimately settling along the various canal routes. Initially hired as laborers to build the canals, many of the Irish stayed on to settle in the villages which sprang up alongside them. This pattern would seem to fit the Seneca Falls situation. A local history states that the first permanent Irish settlers arrived in 1827 and were named Thomas Sullivan and Patrick Quinn. [29] The first Catholic church was built in 1835, but "so rapid was the increase of the Catholic population of the village" says another history, that a much larger church had to be built in 1848. [30]

The years of the heaviest Irish-Catholic influx into the village coincide exactly with the years when the Seneca-Cayuga Canal was being extensively renovated and rebuilt. Although we lack any firm documentation to prove this, it seems probable that the initial Irish settlement in the village occurred as a result of the need for unskilled laborers to help with the construction of the canal. Once the canal had been finished the booming economic condition of the village, combined with the many practical inducements of such promoters as Gary V. Sackett, probably convinced many to settle in Seneca Falls permanently. Their numbers rapidly increased through the 1840s and 1850s as word spread regarding the many opportunities in the town's new factories and mills. By 1862, the number of Irish-Catholics in the village was estimated to be 1,500. [31]

Some of these new Irish immigrants were of course women, but we know even less about them than the men. We have yet to discover any personnel books for any of the factories in this period, so we have no clear indication how many women, Irish or otherwise, might have been working in the mills. The census records do not generally record the occupations of females, even in cases where we know they were earning money. We do know that some women were working at the mills, as Elizabeth Cady Stanton notes in an 1859 letter that, Mary, her cook "went into the factory, as she was tired revolving round the cook stove." [32] What she did there or how much she earned is a mystery.

Other scattered references seem to indicate that many women worked for the factories by doing piecework in their homes, rather than in the factory itself. Charlotte Woodward, one of the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments, earned extra money for her family by sewing gloves which were sent to her home in Dewitt from a factory in Gloversville. [33] An 1860 abstract for the Seneca Knitting Mills lists 350 employees and 3000 "finishers" doing outside work. [34] These 3000 finishers may very well have been women working, like Charlotte Woodward, in their homes.

Even if a woman did not go into a factory to work, or labor over piecework at home, the growing industrialization in the village nevertheless had a profound impact on her life. If nothing else, it somewhat eased the daily burden of living. With factories churning out such items as candles, baskets, stockings, and mattresses by the thousands, women no longer had to spend hours making their own by laborious hand techniques. One local resident remembered how thrilled his mother was when the textile mills opened in the area and she no longer had to produce all her own wool and linen at the farm. Instead, she would exchange raw wool at the mill for "a piece of factory" as she called it, and have it fashioned into clothing for the family by travelling "tailoresses." [35] The pumps for which Seneca Falls was to be so famous also vastly improved the quality of most women's lives. Having an indoor kitchen pump was vastly superior to drawing water for washing, bathing, and cooking from an outdoor well.

Although many women welcomed the material benefits of industrialization, and the opportunity to gain some economic independence, the process often did much to worsen their situation. Although the opportunity to work in a factory was theoretically liberating, in actual fact it often placed a double burden on women. Many were forced to work at uncongenial jobs to earn money which immediately went into the hands of husbands and fathers, and they often had to continue performing the traditional female housekeeping tasks in addition to their factory work.

The change from a family oriented rural lifestyle to one where the male members of the household now worked long hours away from the home, also served to buttress the idea that a woman's sphere was in the home, while a man's natural place was in the vigorous business world. Far from giving women equal economic opportunities, the new industrialization often only served to further circumscribe their lives and aspirations. Part of the frustration that induced women like Charlotte Woodward to attend the Convention was produced by these new stresses which industrialization had brought in its wake.

C. Community Development and Neighborhoods

As with any growing community, Seneca Falls began to organize itself into clearly definable residential and commercial neighborhoods in the 1830s and 1840s. The earliest settlement (1787-1826) had been almost entirely confined to the riverfront near the rapids, and the edges of Fall Street where stores and taverns cropped up to cater to the travellers on the turnpike. With the freeing of the water rights and the opening of the south side after 1826, however, new patterns of settlement emerged. The industrial activity continued to be concentrated around the river frontage, but new commercial and residential areas appeared to support the increasing number of new residents arriving in the village.

It must be emphasized that most of the conclusions in this section of the report were drawn from a very limited study of assessment records, census rolls, maps and personal papers, and can in no way be considered definitive. Further research must be completed in this area before we can be absolutely certain of the village's settlement pattern, but this preliminary study does seem to indicate basic trends and allows us to make some generalizations. Most of the records that were available for this study date from the early to mid-1850s (1850 Census, 1851 Assessment Records, 1852 and 1856 Maps), but as Seneca Falls experienced no great socio-economic upheaval between 1848 and 1856, we can probably safely assume that the trends which appear in these records were the continuation of forces which had certainly begun by 1848.

Local histories and census records indicate that Seneca Falls' population in the 1840s and 1850s was in the 3000-4000 range. The obvious question arises as to where these people were living. Most of them were apparently factory workers, living on fixed incomes. We do not have the personnel records of any of Seneca Falls' early industries, but we do know for instance that in 1862, the Seneca Knitting Mills employed about 400 workers in the factory, with 3000 others doing "finishing work" in their homes. [36] Taking this as a general guideline, we can obtain some idea of the number of people needed to run Seneca Falls' numerous mills and factories. Further study of local gazetteers and business records at the Seneca Falls Historical Society will hopefully provide more information.

A look at the 1851 real estate assessment records shows that a fair number of these people owned their own homes. Approximately 650 separate names appear on the assessment list as property owners. [37] This indicates that there was a house for about every five persons, suggesting a high rate of home ownership given the size of the average mid-19th century family. Assuming that the factory workers had a limited supply of ready cash and would be living in fairly inexpensive housing, a list was made of those individuals whose property was assessed at a value between $100 and $300. These homes would have been decidedly modest, as an unoccupied or abandoned house was usually valued at $100, and many homes in the village were well up into the double figure range. The Stanton House for comparison was valued at $1,500. Fifty-six homes fell into this $100-$300 category, with a high concentration in the south side area bounded by Haigh, Toledo, and Bridge Streets.

This orientation supports the traditional belief that Judge Gary V. Sackett was very active in promoting settlement in the property he owned on the south side of the river. It was said that after he divided the land into lots in 1827, he offered the property on exceptionally easy terms to facilitate the settlement of the area by the Irish-Catholic laborers then flooding into the area. A study of any existing deeds would have to be done to verify this claim, but it certainly appears plausible. The vast majority of small property owners, most of whom had Irish surnames, were indeed located in the Sackett district.

Sackett's enterprising community spirit is well documented through his various commercial, political, and social activities. The fact that he donated the property at the corner of Toledo and Bayard Streets for the new Catholic church in 1848 [38] is a further indication that he was actively promoting Irish worker settlement in the area. At a time when anti-Catholic prejudice was exceedingly strong, Sackett, himself an Episcopalian, was making a strong goodwill gesture by this action. By providing low interest housing loans and familiar community and religious amenities, Sackett was attempting to create a stable and congenial neighborhood for Seneca Falls' newest citizens.

Sackett's activities in this area were suprisingly ahead of their time, and not at all the usual practice among early 19th century real estate barons. Most Yankee citizens were rather frightened by the flood of Irish immigration which engulfed them in the 1840s and 1850s. Suspicious of their religion, and disapproving of their lifestyle, they generally left the Irish to their own devices when it came to finding homes and jobs. The results were often unpleasant, both for the incoming immigrants, and for the old residents who were scandalized by the untidiness and overcrowding which characterized many early Irish communities. As a proud community leader, part of Sackett's motivation in encouraging Irish settlement on his property was no doubt an effort to avoid a similar slum development in Seneca Falls. Simple economic sense also dictated that if he wanted to sell his land, he had to do it to the newcomers, who just happened to be Irish. His intense personal involvement in the neighborhood, however, implies that he was interested in more than just a quiet town and a full pocket.

Sackett himself lived in the area in a large limestone house which he built on Sackett Street across from the Catholic church. His efforts in developing the neighborhood resemble nothing so much as a concentrated effort to create a well-planned, self-contained community specifically for the laboring classes around the Bridge Street artery. A contemporary of Sackett's recalled that the Judge and Ansel Bascom were rivals of a sort in developing the second ward, with Sackett concentrating on the west end, and Bascom on the east. [39] A glance at the 1856 map shows that Sackett won out, at least in the number of residents he attracted. The large commercial block he built at the corner of Bridge and Bayard Streets anchored the neighborhood and added greatly to its prosperity and stability.

This development of a carefully planned working class neighborhood was rather unusual in early mill towns. Although many mill owners did erect housing specifically for their workers, these developments were often tied to one particular factory, with the workers as often as not obliged to live there because the company script they received as wages could be used as rent nowhere else. Seneca Falls never developed this type of factory housing system. Instead, it offered Sackett's traditional neighborhood development with private lots and individual home ownership. The opportunity for a mill hand to actually own his own home and piece of land was extremely rare in the early 19th century. It is a tribute to Sackett's open-mindedness and community spirit that it happened in Seneca Falls.

Not every new worker in the village of course could afford even one of Judge Sackett's reasonable lots. We know that there were boarding houses in the village at this time, as a young machinist mentioned in his memoirs that they would all accept the factory script he received as pay in return for rooms. [40] Unfortunately, we do not know how many there were or where they were located. Interestingly enough, the assessment records seem to indicate that at least some of them might have been situated in the neighborhood of the Wesleyan Chapel.

The 1851 assessment records show that a number of individuals owned multiple modest houses on Mynderse, Clinton, Jefferson, Chapel, and Troy Streets. In almost every case, they also owned a much more substantial house elsewhere in the village. Josiah Miller for example, owned a $1,200 house on Cayuga Street and a $300 house on Mynderse. Joseph Metcalf owned a house and barn valued at $11,000, in addition to a $600 house on Mynderse Street and a house under construction on Jefferson Street. Since these and the dozen other men who owned several houses in the Chapel area could not live in all of them at once, some of the properties must have been rented. Assuming that the owners would be using their most substantial house as their private residence, this leaves a fairly high number of available rental properties surrounding the Chapel. The 1851 assessment roll shows that there were at least 17 houses in the immediate neighborhood of the Chapel, presumably available for rent. Because the assessment records did not always list the location of multiple properties, there may well have been more. The records do seem to indicate that it was a popular area for real estate investments. (See Appendix B.) The 1856 map of the village shows that this trend continued; Josiah Miller and others having acquired several more properties in the area in the intervening five years.

We do not know if these houses were being used as single family dwellings or multiple occupancy boarding houses. Generally speaking, they seem to have been quite modest, only a small step above the houses in the Sackett neighborhood. Most of them fell into the $300-$400 range, with an occasional $600 or $800 house. The census records seem to indicate that there was not a large transient population of unattached adults in the village, most of the workers settling there with their families. Given the presumed size of the rental properties, it appears unlikely that they were run as high occupancy boarding houses, although some of the larger ones certainly might have been. The general impression is that the houses in the vicinity of the Chapel were rented as single family dwellings by members of the working class. Some of the homes may have been shared by more than one family. Duplexes were not unknown in the village as the assessment records indicate that there was a double house in the Sackett district at the corner of Haigh and Swaby Streets. Besides the investment rental properties, the Chapel area was characterized by numerous small property owners much like the Sackett district. Here and there would appear a more substantial house in the $600-$700 range, indicating that at least some of the residents were working their way up the economic ladder.

There seems to have been a small amount of commercial activity in the area as well, as the assessment rolls list one or two unspecified shops connected to homes in the area. These were probably very modest operations, as the maps and records seem to indicate that this was a predominately residential neighborhood. It is interesting to note though, that one local history states that there used to be a brickyard where the second Methodist church now stands on the corner of Clinton and Fall Streets. [41] The 1856 map shows the entire western half of the Clinton/Mynderse Streets block as unsurveyed and undeveloped. Is this the old brickyard? It apparently was no longer in operation in 1856, as the map fails to label it. Although no one has ever mentioned a brickyard next to the Chapel in conjunction with the Convention, it is theoretically possible that one was located there and in operation in 1848. We know that Joseph Metcalf, the founding father of the Wesleyan Chapel, had a brickyard and supplied all the brick for the Franklin House and Sackett's commercial block. He supposedly had a yard at his farm 1-1/2 miles north of the village, but he also owned a building directly behind the Chapel, and may have operated another brickyard operation from there. [42]

The view south from the Chapel was less obstructed in 1848 than it is today. There were several large mills along Water Street, but none of the commercial development along Fall Street which would come later. William Arnett's textile mill (1844) was visible directly to the southeast. Still in operation today is the Seneca Woolen Mill (now known as the Seneca Knitting Mill), the only remaining evidence of the once extensive mill and factory complex which stretched along the riverfront.

D. Stanton House Neighborhood

The chance bit of fate that placed Elizabeth Cady Stanton on the corner of Washington and Seneca Streets in 1847 was instrumental in the development of her women's rights philosophy. By her own admission, her isolated situation and exotic neighbors were part of the stimuli that compelled her to call the Convention. Her particular location in the village provided her with certain opportunities and insights she probably would not have experienced elsewhere.

Stanton was correct when she said that her home was on the outskirts of town. Although living alongside the major east-west axis of the Seneca Turnpike, she was inconveniently far from the south side commercial district which was centered between Bridge and Ovid Streets, and which was a major center of community activity in 1848. The real cause of her isolation was probably her lack of neighbors. For a garrulous energetic woman like Stanton, her situation was decidedly isolated when compared to the cozy neighborhoods her friends lived in throughout the rest of the village. Exactly why the Locust Hill area remained so sparsely settled when businesses and homes were popping up like weeds everywhere else on the south side is unknown. The Seneca Falls Historical Society has an 1853 map in its collection (#A6) which was prepared for an auction sale of the lots lying in the triangle formed by Washington, Seneca, and Bayard Streets. A look at the 1856 map seems to indicate that only two of the 42 lots were sold, if indeed the sale were ever held. Perhaps the owners were asking exorbitant prices, or perhaps that portion of town was simply considered undesirable for one reason or another. In any case, Stanton spent her years in Seneca Falls largely marooned by herself on top of Locust Hill.

She does mention that "there was quite an Irish settlement at a short distance," [43] and the records do indeed show that there were about a dozen families living within the immediate vicinity, most of them along Seneca Street. The assessment records show that most of them, at least by 1851, owned their own homes. (See Appendix C.) Because we lack any other documentation, we can only assume that the individuals who appear on the 1851 list were the same ones who were living there in 1848. As with the Sackett neighborhood and the area around the Chapel, most of the homes have very modest appraisal values ranging from $200-$350. Joseph Payne's brick home was valued at $500.

There is an indication that some type of commercial activity was being pursued along Seneca Street, for an O. R. Wickes, whose property was just below the rear of the Stanton lot, is listed in the assessment rolls as having a house and shop there worth $700. There is no indication what sort of shop it might have been, or whether it was in active operation. James Luce is listed as the owner of the "old sash factory" on Seneca Street, but we do not know whether he was just living there, operating it as a business, or leaving it vacant.

It would be interesting to find out when these dozen, mostly Irish, families moved into the area and why they tended to congregate along the north side of Seneca Street. Might it have had something to do with work on the turnpike which ran in front of their houses, or was it somehow connected with the distillery located behind them on the river? Why did they settle here on the outskirts of town and not in the Sackett district where the majority of Irish were making their homes? At this point we neither know when they settled there, why, or how they made their living. That they were of the working class appears fairly certain, judging by the value of their homes and Stanton's oblique references to them. This, probably more than anything made Stanton feel somewhat isolated. Though the well-to-do Chamberlain family lived at the foot of Seneca Street, Stanton was used to being surrounded by a large number of well-educated and liberal-minded companions, not first generation Irish laborers.

Her unexpected interaction with her neighbors resulted in a valuable eye-opening experience for her. Initially, her relations with them were strained as her children insisted on throwing rocks at their houses and livestock, but as they began to get used to one another, "amicable relations were established." [44] Stanton became something of the neighborhood umpire and midwife, arbitrating her neighbor's squabbles and delivering their babies. Her midnight excursions into their small homes had a profound impact on her, enabling her to see with her own eyes how alcoholism and poverty adversely affected the lives of many women. If she had settled in a comfortable middle class neighborhood among friends and relatives, she would most likely have never set foot in an Irish laborer's home, and learned how harsh life could be for poor women.

Stanton's open, generous nature soon led her to make friends with her neighbors, something many another privileged woman would not have done. She lent them newspapers, gave the children toys and clothing, and shared the family's fruit and produce with them. That her friendship with them was genuine seems certain. Before she ever moved to Seneca Falls she attacked those who were deploring the large Irish immigration caused by the potato famine. "What indescribable suffering the poor Irish must now be undergoing," she wrote her cousin, "The best way to relieve them is to bring them here to our land of plenty. I think instead of mourning over the increase of migration, we should rejoice for surely their condition is improved." [45] She tried to keep in touch with them as well after she left Seneca Falls, once writing to a friend, "I wish you would go down some day and inquire about my neighbors, Old Ann Dunnigan especially, I wish you would read Theodore's letter to her and say that we wish to hear all about her, about Michael, Mary and the dog." [46]

Except for these dozen Irish families, the Chamberlains, and the schoolhouse down the road on Washington Street, there was no other development in the immediate area. Although we cannot know this for certain, it is likely that the area to the south and west of the house was fairly open country. It is not very likely though that the neighborhood enjoyed anything like country quiet. Although the heyday of the turnpike was over by the time the Stantons moved to Seneca Falls, the road ran just alongside their property and was still the major thoroughfare for east-west traffic entering and leaving the village. A fairly steady procession of people and goods must have passed the house each day. Boats still plied the nearby canal as well, with all their attendant noise and confusion. Perhaps the most annoying intrusion was the large mill complex behind Seneca Street. Originally a flour mill, it was converted into a distillery sometime between 1852 and 1856. Less than pleased with the resultant change in the local air quality, Elizabeth Cady Stanton published a note in The Lily thanking the owners "for the magnificant bouquet just presented to her by that firm at a cost of ten thousand dollars." [47]

Figuratively and physically, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was positioned between the pastoral world of the early 1800s and the increasing industrialization of the post-1850 years. She could look out her back door and see fields and fruit trees, and gaze out the front upon churning millwheels and smoking chimneys. Across Bayard Street were the proud scions of old Yankee families, but down the hill were the vigorous families of recent Irish immigrants, struggling to make ends meet. Recognizing the old problems of society, and discovering some new ones along the way, she set in motion a movement that would address them all, and in the end, attempt to redefine society's conception of human worth and expand its notion of justice.

Important Sources of Information and Suggestions for Further Research

1. Seneca Falls Historical Society Collections.

The local Historical Society has a veritable treasure trove of information on the village which to date, has largely gone untapped. Time constraints allowed only a quick survey for this report, but further concentrated research should be done in this area. Important collections include:

Seneca Falls Historical Society Papers—These are papers written or collected by members of the early Historical Society on all aspects of life in the village. They are an incredibly rich source of information, containing many first person narratives from residents who lived here in the early 19th century. Most, if not all, have been bound in a series of books at the Historical Society.

Family Records—The Society has a large collection of papers documenting village families. Though some may contain only one or two items, they provide a wealth of miscellaneous material on the social, economic, and religious life of the community.

Business Records—The collection does not represent all of the industries once active in the village, but does contain early ledgers, accounts, and other business books. No personnel records have yet been found, but they may exist somewhere within the collection.

Assessment Records—Further study of these may help us identify neighborhoods and trace community development.

Newspapers—The Society has a sizeable collection of early 19th century newspapers on microfilm. They provide excellent insight into early community life through advertisements, descriptions of social events, editorials, and human interest stories.

Map Collection—Includes village maps from all time periods. Very valuable for determining when the various historic properties were built or altered.

Photographic Collection—Contains thousands of prints and glass plate negatives of village people, places and events.

2. United States Census Records.

More work should be done with these to help us get a better sense of the community composition. It would be useful to know for instance, exactly how many people were in the Irish families on Seneca Street. Stanton implies that they were overrun with children. Was this really the case?

3. ""Woman's Rights and Other "Reforms" in Seneca Falls:" A Contemporary View" by Mary S. Bull, edited by Robert E. Riegel New York History Vol. XLVI, No. 1 (Jan. 1965). Copy at the Seneca Falls Historical Society.

This particular article is full of information on Stanton, Bloomer and Seneca Falls in the 1840s and 1850s. It was written by Ansel Bascom s daughter who attended the Convention as a girl of 13. First published in the magazine "Good Company" in 1880, it describes the characters and reform movements of Seneca Falls in an engaging, entertaining fashion. Although allowances must be made for Bull's own prejudices, it is a valuable first person account of activities in Seneca Falls. When the article first appeared in 1880, Amelia Bloomer took exception to certain statements in it and wrote a rebuttal. This was printed in the Seneca Falls Revielle on July 30, 1880, and is available at the Historical Society on microfilm. It too contains important information on The Lily and Bloomer's relationship with Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

4. "A Century of Seneca Falls History—Showing the Rise and Progress of a New York State Village." A paper prepared by Edward C. Eisenhart as part of his B.A. degree work at Princeton, 1942. Copy available at the Seneca Falls Historical Society.

A good overview of the village's development in the 19th century. Manages to make sense out of all the complex commercial and industrial activities which characterized the village during that period. Goes beyond the usual listing of factories to which most Seneca Falls histories seem to be addicted.

5. As We Were and Lost & Found, Photographic collections published by the Seneca Falls Historical Society. Contain many early 19th century views of Seneca Falls, including such items as the Stanton House and the Sackett commercial block.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

wori/shs/shs1.htm

Last Updated: 10-Dec-2005