|

Parks, Politics, and the People

|

|

|

Chapter 9: Mission 66 and the Road to the Future Following is a quick checklist of construction accomplishments of Mission 66: Park roads—1,570 miles of reconstructed roads, 1,197 miles of new roads, mostly in new areas, or a total of 2,767 miles. Trails—359 miles of reconstructed trails, 577 miles of new trails, a total of 936 miles. Airport runways—30 miles of runways, all outside the parks. Parking areas—330 parking areas with a total vehicle capacity of 10,868 were reconstructed and repaired. 1,502 new areas with a capacity of 49,797 vehicles were added, giving us a total of 155,306 vehicle capacity in the national park system. Campgrounds—575 new campgrounds increased camping facilities by 17,782 campsites, giving a total, as of 1966, of 29,782 campsites. Picnic areas—742 new picnic areas, which included 12,393 new picnic sites, were added, and thousands of old picnic sites were reconstructed and improved. Campfire circles and amphitheaters—82 campfire circles and amphitheaters with a seating capacity of 30,252 were built, and 6 older campfire circles and amphitheaters with a seating capacity of 4,645 were reconstructed, making a total available seating capacity, in all the areas, of 41,037. Utilities—535 additional water systems, 521 new sewer systems, and 271 power systems were provided. Additions were made to 301 old water systems, 223 old sewer systems, and 126 old power systems. This makes a total of new or additional for the concessionaires of 836 water systems, 744 sewer systems, and 397 power systems. Administrative and service buildings—221 new administrative buildings were constructed, making a total of 1,917 available. Also 36 new service buildings were constructed, making a total of 164, or a total of all administrative and service buildings in the service of 2,081.

Utility buildings—218 new utility buildings were constructed, making a total of 1,152. Historic buildings—458 historic buildings were reconstructed and rehabilitated, costing a total of $15,100,954. Employee residences, dormitories, apartments, etc.—743 additional single and double housing units and 496 multiple houses, or a total of 1,239 structures, were constructed. Comfort stations—584 new comfort stations were built, and 17 were rehabilitated, for a total of 601. Interpretive roadside and trailside exhibits—we built new, replaced, or rehabilitated a total of 1,116 roadside or trailside exhibits. Marina improvements—50 marinas, boat launching ramps, and beach facilities were built and boat docks were constructed or reconstructed. Other facilities—9 new fire lookout towers, 39 new entrance stations, and 37 new trailer sanitation disposal systems were built.

Training facilities—We established two training centers, one on the south rim of Grand Canyon and one at Harper's Ferry, West Virginia. The one at Harper's Ferry, named the Stephen T. Mather Interpretive Training and Research Center in honor of the service's first director, not only is a training center for rangers and administrative employees but recently has been enlarged to include offices and shops for the planning and construction of interpretive services and devices. The main building is part of the old Stover College, which had been closed for several years before it was purchased and developed for its present purpose. The Horace M. Albright Training Center, named in honor of the service's second director and located in Grand Canyon National Park, was built at a cost of $331,000 primarily for the training of new rangers, though it is also used for advanced training of rangers and other personnel. Visitor centers—Mission 66 studies indicated that the museums that existed in the parks were not adequately serving the public. The Park Service decided to change its visitor facilities from small, museum-type buildings to structures of open design that would include information and interpretive facilities, exhibits, and rest areas. The resulting "visitor center" concept is being used widely in the parks. It has been adopted by a number of federal and state agencies and also by private enterprises, such as power plants, to inform the public of their services. The more elaborate centers in larger parks have souvenir sales, food services, and complex audiovisual equipment; a few have small auditoriums. In some instances the visitor center and park administrative offices are under one roof. During Mission 66, 114 visitor centers were built.

Generally speaking, we greatly improved the operation of parks by giving them adequate facilities and by giving maintenance high priority. Further, Mission 66 was able to stimulate better cooperation between the concessionaires and the government through such arrangements as providing utilities on a rental basis. The concessionaires invested more than $33 million of private funds during the Mission 66 period for new and improved cabins, lodges, motels, stores, curio shops, service stations, marinas, and other installations. An example was the building of the new Canyon Village and Grant Village in Yellowstone National Park and removal of the Old Canyon Lodge Hotel and cabins from the rim of the colorful Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone.

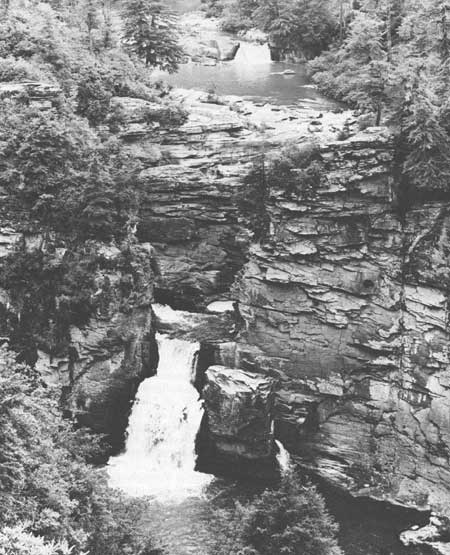

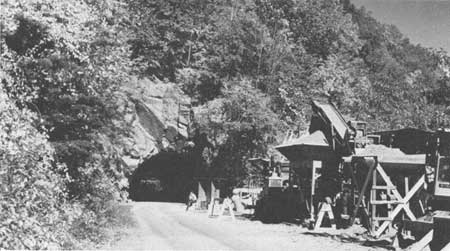

One of the major projects undertaken by Mission 66 was the 469-mile Blue Ridge Parkway, connecting Shenandoah National Park, in Virginia, with Great Smoky Mountains National Park, in North Carolina and Tennessee, via North Carolina. This project was suggested by the late Senator Harry F. Byrd, of Virginia, early in 1933 when President Roosevelt made his first inspection of some of the CCC camps in the national forests and national parks of Virginia. Roosevelt thought well of the parkway idea, and shortly afterwards construction was started under the National Industrial Recovery Act of June 16, 1933. Specific legislative authority was enacted by Congress in 1936. Work proceeded as the land was acquired, all through the thirties, with Public Works Administration funds. As World War II approached, funds were diverted to needs related to the war. By the time Mission 66 was started only about one-third of the distance of the parkway had been completed and made usable. Most of the work had been in places where construction was less difficult. Under Mission 66 funds were included to complete the parkway. The Forest Service worked in cooperation with the National Park Service on this project. We fully intended to complete the Blue Ridge Parkway during Mission 66 and came very near doing it, even though some of the contracts were not completed until a few years after 1966. The one unresolvable issue was a ten-mile stretch on the slopes of Grandfather Mountain for which the state could not get the right-of-way. The owner, Hugh Morton, was quite a political power in North Carolina, and he did not want us to scar up the mountain. We and the state spent a lot of time negotiating with him, to no avail. In the end, Mission 66 provided better than 75 per cent of the cost of construction of the entire Blue Ridge Parkway.

|

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

| ||

Parks, Politics, and the People ©1980, University of Oklahama Press wirth2/chap9d.htm — 21-Sep-2004 Copyright © 1980 University of Oklahoma Press, returned to the author in 1984. Offset rights University of Oklahoma Press. Material from this edition may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the heir(s) of the Conrad L. Wirth estate and the University of Oklahoma Press. | ||