MENU

![]() Response to ANCSA, 1971-1973

Response to ANCSA, 1971-1973

|

The National Park Service and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980: Administrative History Chapter Three: Response to ANCSA, 1971-1973 |

|

D. The Morton Proposals

On December 17, 1972, Interior Secretary Morton forwarded the proposed legislation to Congress. The bill, which, he said, sought to preserve some of the most "majestic territory on earth, along with lands and rivers that support some of the most exciting fish and wildlife," was the product of considerable negotiation and compromise, and sought to strike a balance between potential resource users. If this had not been accomplished, concluded Morton, "we have erred on the side of conservation." [116]

Secretary Morton proposed adding 83,470,000 acres to the National Park, Wildlife Refuge, Forest, and Wild and Scenic Rivers systems. [117] Included were additions to Mount McKinley National Park and Katmai National Monument (which would become Katmai National Park with passage of the bill), establishment of three new parks, four national monuments, one national river, and one national reserve. The total acreage recommended, which would more than double the size of the existing park system, was 32,600,000 acres:

| Mount McKinley National Park additions | 3,180,000 | |

| Katmai National Park additions | 1,187,000 | |

| Aniakchak Caldera National Monument | 440,000 | |

| Harding Icefield-Kenai Fjords National Monument | 300,000 | |

| Cape Krusenstern National Monument | 350,000 | |

| Kobuk Valley National Monument | 1,850,000 | |

| Lake Clark National Park | 2,610,000 | |

| Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park | 8,640,000 | |

| Gates of the Arctic National Park | 8,360,000 | |

| Yukon-Charley National Rivers | 1,970,000 | |

| Chukchi-Imuruk National Reserve | 2,690,000 | [118] |

Nine areas totalling 31,590,000 acres would be added to the National Wildlife Refuge system. The 18,800,000 acres of proposed new national forests were those agreed to by Secretaries Morton and Butz in October. Additions to the Wild and Scenic Rivers System (820,000 acres) would have included sixteen rivers within d-2 areas and four more—Beaver Creek, Fortymile, Birch Creek, and Unalakeet—outside.

The bill proposed joint management for four areas. The Park Service and BSF&W would manage Chukchi-Imuruk National Reserve and the two southern units of Harding Icefield-Kenai Fjords. The BSF&W and BLM would cooperate to manage Iliamna National Resource Range and Noatak National Arctic Range. [119]

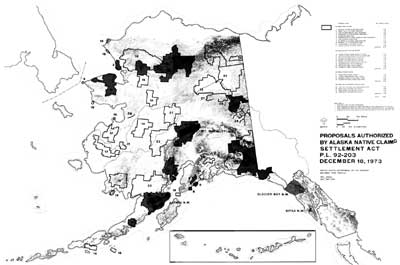

Proposals

Authorized by Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, P.L. 92-203, December

18, 1973.

(click on map for larger size)

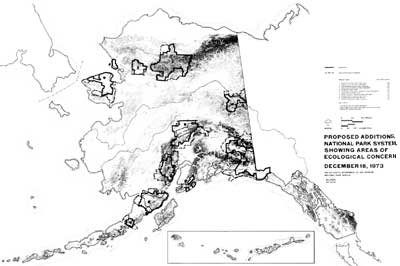

The proposal provided for continued traditional subsistence uses in all d-2 areas and withdrew all park areas except the Charley River watershed in the Yukon-Charley National Rivers from all forms of appropriation including mineral leasing laws, and provided for a three-year wilderness review. It would have allowed the Secretary of Interior to enter into cooperative agreements concerning the use of privately owned lands adjacent the park areas. These lands, known as areas of ecological concern, were not part of the system, but were critical to the ecosystem of the park. [Illustration 10]. [120]

Proposed Additions, National

Park System Showing Areas of Ecological Concern, December 18,

1973.

(click on map for larger size)

In terms of the Park Service, the most controversial provision in the bill was that which would have allowed the continuation of sport hunting in Aniakchak, Lake Clark, Wrangell-St. Elias, Gates of the Arctic, Chukchi-Imuruk, and Yukon-Charley National Rivers. Conventional wisdom in the Service suggests that the provision for sport hunting in park areas, which was included at the insistence of the Interior Department over the opposition of the Park Service, resulted from the September 1972 agreement between the state of Alaska and Secretary Morton. [121] That agreement, however, referred only to sport hunting in selected townships of the proposed Aniakchak Caldera National Monument. Provision for sport hunting in the other areas seems to have been more a response to pressure from wildlife management and hunting groups. Secretary Morton's desire to appeal to the widest possible constituency also seems a more compelling reason, although it is likely that the agreement to allow hunting at Aniakchak did make it easier to allow it elsewhere. [122]

Perhaps because Secretary Morton had tried to achieve a balance between competing interest groups, the proposal succeeded in pleasing very few. Forest Service representatives admitted that they were not completely satisfied with the way things came out. Many Alaskans, including the congressional delegation, governor, and editorial opinion in the state, opposed the proposal as one that would strangle the state's economy by "locking up" too much land in parks and refuges, rather than in multiple-use areas. In March state officials indicated that they would go to court to protest the proposals. [124]

Conservationists, on the other hand, had viewed the decision-making process leading to the proposal with growing dismay, as more and more lands they believed should be preserved as parks and refuges found their way into multiple-use categories. In May the Wilderness Society had taken out a full-page newspaper advertisement to bring pressure on Secretary Morton. On November 30, the Wilderness Society, National Audubon Society, Sierra Club, and Friends of the Earth formed the Emergency Wildlife and Wilderness Coalition for Alaska, taking its campaign to the public with advertisements in major newspapers across the country in an attempt to reverse decisions already made. By November 1973 both the Sierra Club and Wilderness Society had completed draft legislation that proposed setting aside 119,600,000 acres of land in Alaska. Included were 62,000,000 acres of national parks:

| Gates of the Arctic National Park | 12,200,000 | |

| Yukon-Charley National Park | 2,200,000 | |

| Kobuk Valley National Monument | 2,200,000 | |

| Cape Krusenstern National Monument | 300,000 | |

| Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park | 18,100,000 | |

| Lake Clark National Park | 7,200,000 | |

| Aniakchak Caldera National Monument | 800,000 | |

| Mount McKinley National Park additions | 4,200,000 | |

| Katmai National Monument additions | 2,600,000 | |

| Noatak National Ecological Reserve | 7,300,000 | |

| Chukchi-Imuruk National Ecological Reserve | 4,300,000 | |

| Kenai Fjords National Ecological Reserve | 600,000 | [125] |

For the National Park Service, the Morton proposal was a bitter-sweet one. The bill proposed to double the size of the National Park System in one fell swoop with areas of unsurpassed grandeur. [126] Yet at the same time, NPS planners were distressed over the loss of the Noatak, which Francis Williamson had called the "best all-around choice made by the Task Force" [127] The proposed 5,500,000-acre Wrangell National Forest on the flanks of Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park seemed to NPS planners to be a particularly "obscene" arrangement, leaving as it did, a park consisting primarily of "rock and ice." Equally galling to Alaska planners, was the failure to include a strong regional planning provision, something which most involved felt would be essential for the future of the Alaska parks, and loss of wilderness designation for Gates of the Arctic National Park. [128]

The provision that allowed for continued sport hunting in proposed new park units proved especially disturbing, flying, as it did, in the face of a tradition of an opposition to hunting in the national parks that dated to the earliest general statement of National Park Service policy in 1918. [129] There is some evidence to suggest, it is true, that when Interior Department officials included a hunting provision to placate hunting interests, no one seriously expected that it would survive congressional scrutiny. [130] Nevertheless, the provision concerned a great many, although by no means all, NPS employees, their allies in the conservation community, and counterparts in the Canadian National Parks. [131]

There is no doubt that the Morton proposal had serious shortcomings. It would have benefitted from additional study and planning. The Secretary had, of course, no choice but to submit the proposal on that date. Congress had mandated the date for submission of the proposals in ANCSA, however unrealistic that date might have been. In retrospect, it seems that, given the political considerations under which bureau and departmental officials worked, the need to listen to and balance all views, the state of the knowledge of the Alaskan areas, the too-limited time frame mandated by Congress for submission of recommendations, and uncertainty that existed regarding Native land selections, the Morton proposal went as far as was then possible. It defined areas upon which others would build. In the areas of ecological concern NPS and Department of the Interior officials had been able to make public what they considered to be ideal boundaries for the proposed park units. Later proposals would represent, in large part, extensions into those 1973 areas of ecological concern. [132] Lastly, the recommendation of 83,000,000 acres broke a psychological barrier, by making a clear statement that the 80,000,000-acre limitation of section 17(d)(2) did not bind the legislative recommendations of the Secretary of the Interior. It established, finally, a base below which any future administration would find it difficult to go.

Between January 1, 1972 and December 18, 1973, the Interior Department and individual bureau staffs had expended enormous amount of time in preparation of the legislative recommendations mandated by ANCSA. [133] Compromise that was often painful to agency professionals, however, characterized the decision-making process that led to the recommendations forwarded to Congress by Secretary Morton on December 17, 1973. At each stage the various interest groups had the opportunity to argue their views, and the final product was an effort to balance their interests. Yet despite the debate that had taken place and the compromises made, it became clear almost as soon as Secretary Morton forwarded the proposal that passage of any bill that provided for additions to the four systems in Alaska would come only after a long and arduous process. On January 29 Congressman James Haley introduced the Morton proposal as H.R. 12336, and the next day Senator Henry Jackson introduced the Senate version of the bill. [134] At the same time Jackson introduced, at the behest of conservationists, a bill calling for the addition of 106,094,000 acres to the four conservation systems. [135] Over the next several months other bills had been introduced to establish a cultural park in the Brooks Range (Nunamuit National Wildland) and to increase the number of wildlife refuges in Alaska. [136] Additionally, others began to work up proposals, and members of the Alaska Congressional delegation indicated that alternative legislative proposals would be forthcoming. [137]

These were only the first of a sometimes bewildering array of bills introduced over the next several years regarding the National Interest Lands in Alaska. For seven years the question would be before Congress. By the time a bill finally passed in 1980, the question had become the most thoroughly debated one of the history of conservation in the United States.

End of Chapter Three

Top

Top

Last Modified: Tues, Jan 9 2001 10:08 am PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/williss/adhi3d.htm

![]()