| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

SECURING THE SURRENDER: Marines in the Occupation of Japan by Charles R. Smith Requirements for clothing, ordnance, and equipment and supplies had to be determined and arranged for from the 5th Field Service Depot. Initially, this proved to be difficult due to the secret nature of the operation and that all requisitions for support from supply agencies and the Island Command on Guam had to be processed through III Amphibious Corps. At 0900 on 12 August, the veil of secrecy surrounding the proposed operation was lifted so that task force units could deal directly with all necessary service and supply agencies. All elements of the task force and the 5th Field Service Depot then went on a 24-hour work day to complete the resupply task. The regiment not only lacked supplies, but it also was understrength. Six hundred enlisted replacements were obtained from the FMFPac Transient Center, Marianas, to fill gaps in its ranks left by combat attrition and rotation to the United States. Dump areas and dock space were allotted by the Island Command to accommodate the five transports, a cargo ship, and a dock landing ship of Transport Division 60 assigned to carry Task Force Able. The mounting-out process was considerably aided by the announcement that all ships would arrive in port on 14 August, 24 hours later than originally scheduled. On the evening of the 13th, however, "all loading plans for supplies were thrown into chaos" by information that the large transport, Harris (APA 2), had been deleted from the group of ships assigned and that the Grimes (APA 172), a smaller trans port with 50 percent less capacity, would be substituted. The resultant reduction of shipping space was partially made up by the assignment of a landing ship, tank (LST) to the transport group. III Amphibious Corps informed the task force that no additional ship would be allocated. Later, after the task force departed Guam, a second LST was allotted to lift a portion of the remaining supplies and equipment, including the amphibian tractors of Company A, 4th Amphibian Tractor Battalion. On the afternoon of 14 August, loading began and continued throughout the night. The troops boarded between 1000 and 1200 the following day, and by 1600 all transports were loaded. By 1900 that evening, the transport division was ready to sail for its rendezvous at sea with the Third Fleet. Within approximately 96 hours, the regimental combat team, it was reported, "had been completely re-outfitted, all equipment deficiencies corrected, all elements provided with an initial allowance to bring them up to T/O and T/A levels, and a thirty day re-supply procured for shipment." Two days prior to the departure of the main body of Task Force Able, General Clement and the nucleus of his headquarters staff left Guam on the landing ship, vehicle Ozark (LSV 2), accompanied by the Shadwell (LSV 15) and two destroyers, to join the Third Fleet. As no definite mission had been assigned to the force, little preliminary planning had taken place so time enroute was spent studying intelligence summaries of the Tokyo area. Few maps were available and those that were proved to be inadequate. The trip to the rendezvous point was uneventful except for a reported torpedo wake across the Ozark's bow. Several depth charges were dropped by the destroyer escorts with unknown results. Halsey's ships were sighted on 18 August, and next morning, Clement and key members of his staff transferred to the battleship Missouri (BB 63) for the first of several rounds of conferences on the upcoming operation. At the conference, Task Force 31 was tentatively established and Clement learned, for the first time, that the Third Fleet Landing Force would play an active part in the occupation of Japan by landing on Miura Peninsula, 30 miles southwest of Tokyo. The primary task assigned by Admiral Halsey to Clement's forces was seizure and occupation of Yokosuka airfield and naval base in preparation for initial landings by air of the 11th Airborne Division. Located south of Yokohama, 22 miles from Tokyo, the sprawling base contained two airfields, a seaplane base, aeronautical research center, optical laboratory, gun factory and ordnance depot, torpedo factory, munitions and aircraft storage, tank farms, supply depot, ship yard, and training schools and hospitals. During the war approximately 70,000 civilians and 50,000 naval ratings worked or trained at the base. Collateral missions included the demilitarization of the entire Miura Peninsula, which formed the western arm of the headlands enclosing Tokyo Bay, and the seizure of the Zushi area, including Hayama Imperial Palace, General MacArthur's tentative headquarters, on the southwest coast of the peninsula. Two alternative schemes of maneuver were proposed to accomplish these missions. The first contemplated a landing by assault troops on the beaches near Zushi, followed by a five-mile drive east across the peninsula in two columns over the two good roads to secure the naval base for the landing of supplies and reinforcements. The second plan involved simultaneous landings from within Tokyo Bay on the beaches and docks of Yokosuka naval base and air station, to be followed by the occupation of the Zushi area, thus sealing off and then demilitarizing the entire peninsula. The Zushi landing plan was preferred since it did not involve bringing ships into the restricted waters south of Tokyo Bay until assault troops had dealt with "the possibility of Japanese treachery." Following the conference, Admiral Halsey recommended to Lieutenant General Robert L. Fichelberger, commander of the Eighth Army, whom MacArthur had appointed to command forces ashore in the occupation of northern Japan, that the Zushi plan be adopted. At 1400 on 19 August, Task Force 31 was officially organized and Admiral Badger formed the ships assigned to the force into a separate tactical group, the transports and large amphibious ships in column, with circular screens composed of destroyers and high speed transports. In addition, three subordinate task units were formed: Third Fleet Marine Landing Force; Third Fleet Naval Landing Force; and a landing force of sailors and Royal Marines from Vice Admiral Sir Bernard Rawling's British Carrier Task Force. To facilitate organization and establish control over the three provisional commands, the transfer of American and British sailors and Marines and their equipment to designated transports by means of breeches buoys and cargo slings began immediately. Carriers, battleships, and cruisers were brought along both sides of a transport to expedite the operation. In addition to the landing battalions of sailors and Marines, fleet units formed base maintenance companies, a naval air activities organization to operate Yokosuka airfield, and nucleus crews to seize and secure Japanese vessels. In less than three days, the task of transferring at sea some 3,500 men and hundreds of tons of weapons, equipment, and ammunition was accomplished without accident. As soon as they reported on board their transports, the newly organized units began an intensive program of training for ground combat operations and occupation duties.

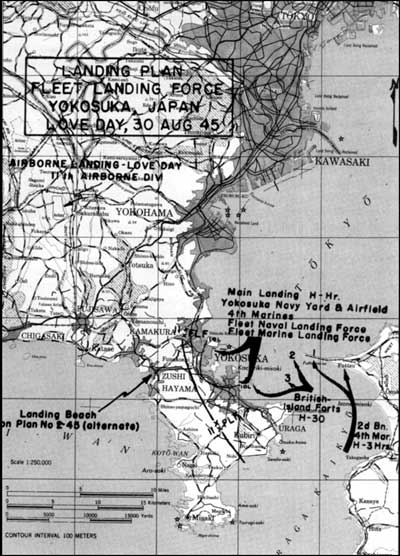

On 20 August, the ships carrying the 4th Marine Regimental Combat Team joined the burgeoning task force and General Clement and his staff transferred from the Ozark to the Grimes. Clement's command now included the 5,400 men of the reinforced 4th Marines; a three-battalion regiment of approximately 2,000 Marines from the ships of Task Force 38; 1,000 sailors from Task Force 38 organized into two landing battalions; a battalion of nucleus crews for captured shipping; and a British battalion of 200 sea men and 250 Royal Marines. To act as a floating reserve, five additional battalions of partially equipped sailors were organized from within Admiral McCain's carrier battle group. The next day, General Fichelberger, who had been informed of the alternative plans formulated by Admirals Halsey and Badger, directed that the landing be made at the naval base rather than in the Zushi area. Although there was mounting evidence that the enemy would cooperate fully with the occupying forces, the Zushi area, Fichelberger pointed out, had been selected by MacArthur as his headquarters area and was therefore restricted. His primary reason, however, for selecting Yokosuka rather than Zushi as the landing site involved the overland movement of the landing force. "This overland movement [from Zushi to Yokosuka]," Brigadier General Metzger later noted, "would have exposed the landing force to possible enemy attack while its movement was restricted over narrow roads and through a series of tunnels which were easily susceptible to sabotage. Further, it would have delayed the early seizure of the major Japanese naval base." Fichelberger's dispatch also included information that the 11th Airborne Division would make its initial landing at Atsugi airfield, a few miles northwest of the northern end of the Miura Peninsula, instead of at Yokosuka. The original plans, which were prepared on the assumption that General Clement's men would seize Yokosuka airfield for the airborne operation, had to be changed to provide for a simultaneous Army-Navy landing. A tentative area of responsibility, including the cities of Uraga, Kubiri, Yokosuka, and Funakoshi, was assigned to Clement's force. The remainder of the peninsula was assigned to Major General Joseph M. Swing's 11th Airborne Division. While Fichelberger's directive affected the employment of the Fleet Landing Force it did not place the force under Eighth Army control.

To insure the safety of allied warships entering Tokyo Bay, Clement's operation plan detailed the British Landing Force to occupy and demilitarize three small island forts in the Uraga Strait at the entrance to Tokyo Bay. To erase the threat of shore batteries and coastal forts, the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines, supported by an underwater demolition team and a team of 10 Navy gunner's mates to demilitarize the heavy coastal defense guns, was given the mission of landing on Futtsu Saki, a long, narrow peninsula which jutted from the eastern shore into Uraga Strait at the mouth of Tokyo Bay. After completing its mission, the battalion was to reembark in its landing craft to take part in the main landing as the regiment's reserve battalion. Nucleus crews from the Fleet Naval Landing Force were to enter Yokosuka's inner harbor prior to H-Hour and take possession of the damaged battleship Nagato, whose guns commanded the landing beaches. The 4th Marines, with the 1st and 3d Battalions in assault, was scheduled to make the initial landing at Yokosuka on L-Day. The battalions of the Fleet Marine and Naval Landing Forces were to land in reserve and take control of specific areas of the naval base and airfield, while the 4th Marines pushed inland to link up with elements of the 11th Airborne Division landing at Atsugi airfield. The cruiser San Diego (CL 53), Admiral Badger's flagship; 4 destroyers; and 12 assault craft were to be prepared to furnish naval gunfire support on call. Four observation planes were assigned to observe the landing, and although there were to be no combat planes in direct support, more than 1,000 carrier-based planes would be armed and available if needed. Though it was hoped that the Yokosuka landing would be uneventful, Task Force 31 was prepared to deal with either organized resistance or individual fanaticism on the part of the Japanese. L-Day was originally scheduled for 26 August, but on the 20th, storm warnings indicating that a typhoon was developing 300 miles to the southeast forced Admiral Halsey to postpone the landing date to the 28th. Ships were to enter Sagami Wan, the vast outer bay which led to Tokyo Bay, on L minus 2 day. To avoid the typhoon, all task forces were ordered to proceed southwest toward a "temporary point" off Sofu-gan, where they were replenished and refueled. On 25 August, word was received from General MacArthur that the typhoon danger would delay Army air operations for 48 hours, and L-Day was consequently set for 30 August, with the Third Fleet entry into Sagami Wan on the 28th.

The Japanese had been instructed as early as 15 August to begin minesweeping in the waters off Tokyo to facilitate the operations of the Third Fleet. On the morning of the entrance into Sagami Wan, Japanese emissaries and pilots were to meet with Rear Admiral Robert B. Carney, Halsey's Chief of Staff, and Admiral Badger on board the Missouri to receive instructions relative to the surrender of the Yokosuka Naval Base and to guide the first allied ships into anchorages. Halsey was not anxious to keep his ships, many of them small vessels crowded with troops, at sea in typhoon weather, and he asked and received permission from MacArthur to put into Sagami Wan one day early. Early on the 27th, the Japanese emissaries reported on board the Missouri. Several demands were presented, most of which centered upon obtaining information relative to minefields and shipping channels. Japanese pilots and interpreters were then put on board a destroyer and delivered to the lead ships of Task Force 31. Due to a lack of suitable minesweepers which had prevented the Japanese from clearing Sagami Wan and Tokyo Bay, the channel into Tokyo Bay was immediately check-swept with negative results. By late afternoon, the movement of Admiral Badger's task force to safe anchorages in Sagami Wan was accomplished without incident. At 0900 on 28 August, the first American task force, consisting of the combat elements of Task Force 31, entered Tokyo Bay and dropped anchor off Yokosuka at 1300. During the movement, Naval Task Forces 35 and 37 stood by to provide fire support if needed. Carrier planes of Task Force 38 conducted an air demonstration in such force "as to discourage any treachery on the part of the enemy." In addition, combat air patrols, direct support aircraft, and planes patrolling outlying airfields flew low over populated areas to reinforce the allied presence. Shortly after anchoring, Vice Admiral Michitore Totsuka, Commandant of the First Naval District and Yokosuka Naval Base, and his staff reported to Admiral Badger in the San Diego for further instructions regarding the surrender of his command. They were informed that the naval base area was to be cleared of all personnel except for skeletal maintenance and guard crews; guns of the forts, ships, and coastal batteries commanding the bay were to be rendered inoperative; the breech blocks were to be removed from all antiaircraft and dual-purpose guns and their positions marked with white flags visible four miles to seaward; and, Japanese guides and interpreters were to be on the beach to meet the landing force. Additionally, guards were to stationed at each warehouse and building with a complete inventory on its contents and appropriate keys.

As the naval commanders made arrangements for the Yokosuka landing, a reconnaissance party of Army Air Force technicians with emergency communications and airfield engineer equipment landed at Atsugi airfield to prepare the way for the airborne operation on L-Day. Radio contact was established with Okinawa where the 11th Division was waiting to execute its part in Blacklist. The attitude of the Japanese officials, both at Yokosuka and Atsugi, was uniformly one of outward subservience and docility. But years of bitter experiences caused many allied commanders and troops to view the emerging picture of the Japanese as meek and harmless with a jaundiced eye. As Admiral Carney noted at the time: "It must be remembered that these are the same Japanese whose treachery, cruelty, and subtlety brought about this war; we must be continually vigilant for overt treachery. . . They are always dangerous." During the Third Fleet's first night at anchor, there was a fresh reminder of Japanese brutality. Two British prisoners of war hailed one of the fleet's picket boats in Sagami Wan and were taken on board the San Juan (CL 54), command ship of the specially constituted Allied Prisoner of War Rescue Group. Their description of life in the prison camps and of the extremely poor physical condition of many of the prisoners, later confirmed by an International Red Cross representative, prompted Halsey to order the rescue group into Tokyo Bay and to stand by for action on short notice. At 1420 on the 29th, Admiral Nimitz arrived by seaplane from Guam and authorized Halsey to begin rescue operations immediately, although MacArthur had directed the Navy not begin recovery operations until the Army was ready. Special teams, guided by carrier planes overhead, quickly began the task of bringing in allied prisoners from the Omori and Ofuna camps and the Shanagama hospital. By 1910 that evening, the first prisoners of war arrived on board the hospital ship Benevolence (AH 13), and at midnight 739 men had been brought out. After evacuating camps in the Tokyo area, the San Juan moved south to the Nagoya Hamamatsu area and then north to the Sendai-Kamaishi area. During the next 14 days, more than 19,000 allied prisoners were liberated.

Also that evening, for the first time since Pearl Harbor, the ships of the Third Fleet were illuminated. As General Metzger later remembered: "Word was passed to illuminate ship, but owing to the long wartime habit of always darkening ship at night, no ship would take the initiative in turning their lights on. Finally, after the order had been repeated a couple of times lights went on. It was a wonderful picture with all the ships flying large battle flags both at the foretruck and the stern. In the background was snowcapped Mount Fuji." Movies were shown on the weather decks. While the apprehension of some lessened, lookouts were still posted, radars continued to search, and the ships remained on alert. Long before dawn on L-Day, three groups of Task Force 31 transports, with escorts, moved from Sagami Wan into Tokyo Bay. The first group of transports carried the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines; the second the bulk of the landing force, consisting of the rest of the 4th Marines and the Fleet Marine and Naval Landing Forces; and the third, the British Landing Force. All plans of the Yokosuka Occupation Force had been based on an H-Hour for the main landing of 1000, but last-minute word was received from General MacArthur on the 29th that the first transport planes carrying the 11th Airborne Division would be landing at Atsugi airfield at 0600. To preserve the value and impact of simultaneous Army-Navy operations, Task Force 31's plans were changed to allow for the earlier landing time. As their landing craft approached the beaches of Futtsu Saki, the Marines of 2d Battalion, 4th Marines spotted a sign left on shore by their support team: "US NAVY UNDERWATER DEMOLITION TEAMS WELCOME MARINES TO JAPAN." At 0558, the ramps dropped and Company G, under First Lieutenant George B. Lamberson, moved ashore. While Lamberson's company and another seized the main fort and armory, a third landed on the tip of the peninsula and occupied the second fort. The Japanese, they found, had followed their instructions to the letter. The German made coastal and antiaircraft guns had been rendered useless and only a 22-man garrison remained to oversee the peaceful turnover. As the Japanese soldiers marched away, the Marines, as Staff Sergeant Edward Meagher later reported, "began smashing up the rifles, machine guns, bayonets and antiaircraft guns. They made a fearful noise doing it. Quite obviously, they hadn't enjoyed doing anything so much in a long, long time." By 0845, after raising the American flag over both forts, the battalion, its mission accomplished, reembarked for the Yokosuka landing, scheduled for 0930. With the taking of the Futtsu Saki forts and the landing of the first transports at Atsugi, the occupation of Japan was underway. With first light came dramatic evidence that the Japanese would comply with the surrender terms. Lookouts on board Task Force 31 ships could see white flags flying over abandoned and inoperative gun positions. A 98-man nucleus crew from the battleship South Dakota (BB 57) boarded the battle ship Nagato at 0805 and received the surrender from a skeleton force of officers and technicians; the firing locks of the ship's main battery had been removed and all secondary and antiaircraft guns relocated to the Navy Yard. "At no time was any antagonism, resentment, arrogance or passive resistance encountered; both officers (including the captain) and men displaying a very meek and subservient attitude," noted Navy Captain Thomas J. Flynn in his official report. "It seemed almost incredible that these bowing, scraping, and scared men were the same brutal, sadistic enemies who had tortured our prisoners, reports of whose plight were being received the same day." The morning was warm and bright. There was hardly a ripple on the water as the 4th Marines, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, scrambled into landing craft. Once on board, they adjusted their heavy packs and joked and laughed as the coxswains powered the craft toward the rendezvous point a few miles off shore. Officers and senior enlisted men reminded their marines of orders given days before: weapons would be locked and not used unless fired upon; insulting epithets in connection with the Japanese as a race or individuals would not be condoned; and all personnel were to present a smart military bearing and proper deportment. "When you hit the beach, Navy cameramen who will land earlier will be there," Lieutenant Colonel George B. Bell said to the men of the 1st Battalion. "They will be taking pictures. Pictures of you men landing. I don't want any of you mugging the lenses. Simply get ashore as quickly as possible and do your job."

|