|

VOYAGEURS

Eighty Years in the Making A Legislative History of Voyageurs National Park |

|

CHAPTER 2

DEVELOPING A PROPOSAL FOR VOYAGEURS NATIONAL PARK

INITIAL STUDIES

1962—EARLY 1963

With NPS Director Wirth's authorization for advanced studies in hand, NPS personnel began laying the framework for detailed field investigations of the Kabetogama area. The scope of the study was outlined in a June 21, 1962 memorandum addressed to Midwest Regional Director Howard Baker from Assistant Regional Director Chester C. Brown. [49] The objective of the memorandum was to provide background information to Director Wirth who was scheduled to visit northeastern Minnesota during the last week in June. Wirth was to be the honored guest of Governor Andersen at the dedication of Minnesota's newest park—Bear Head Island State Park near Tower.

Following the dedication, Andersen and Wirth would be joined for a reconnaissance journey through the Kabetogama-Rainy Lakes area by naturalist and writer Sigurd Olson, Russell Fridley, director of the Minnesota Historical Society, Judge U.W. Hella, director of the Minnesota Division of State Parks, and George Amidon, senior official with the M&O Paper Company, the largest landowner on the Kabetogama Peninsula. Arrangements for this three-day event were made in the governor's office and were planned to acquaint and impress Director Wirth the beauty of the area and, more importantly, to publicly announce NPS interest in the Kabetogama area as a potential site for a unit within the National Park System.

The memorandum prepared by the assistant regional director turned out to be more than just an informative piece for his superiors. Careful study of its contents reveals some very important concepts and opinions about Kabetogama based on over twenty years of NPS experience in the region. As we have seen, the NPS was no stranger to northeastern Minnesota. It had assisted the Minnesota State Parks Division in its initial park and recreational plan (1939) and returned again in the 1950s to help with the update of that plan. The Brown memorandum shows that the NPS did not view the Kabetogama Peninsula in isolation but rather as Brown observed, "an integral part of the total northern Minnesota border complex—the voyageurs route, if you will. In our study, we hope to recognize this, pointing our report specifically at the general Kabetogama area perhaps, but making complementary recommendations on other portions of the border country." [50]

The memorandum is also specific in designating for detailed study the "whole area east of International Falls to the Quetico-Superior/BWCAW region including Kabetogama Lake, the Kabetogama Peninsula, Namakan Lake, Sand Point Lake and Crane Lake." [51] Thus it is clear that national park planners saw an excellent opportunity to complete a federal recreation corridor from Lake Superior to International Falls. The Crane-Rainy Lakes section was the last large missing segment in that corridor.

The reference in the Brown memorandum to the voyageurs route also recognized the historical significance of the border lakes region. In this they were strongly influenced by Sigurd Olson, northern Minnesota's most outstanding authority on the "voyageurs highway" and one of the most articulate advocates for public control of the entire border waterway region.

The memorandum also stressed that the study area included some scenic, geologic, archeological, and ecological features and characteristics not then included in the NPS and that the water-based orientation to recreational opportunities would also give it unusual status within the system. However, this document also expressed some reservations about the Kabetogama area's qualifications for national park status. The stability of the water levels of all the lakes in the proposed study area—Rainy, Kabetogama, Namakan, Sand Point and Crane, are to a greater or lesser degree affected by two dams that were built at Kettle Falls early in the century. Chester Brown, in noting this alteration of natural conditions in his June 1962 memorandum to the regional director, said it presented some difficulty for him in considering the area for national park status. John Kawamoto, the NPS's key planner for Voyageurs, said that later on this situation presented a problem for some park officials as they moved toward a formal position and proposal for the park. [5]

Some thoughts regarding NPS management of the Kabetogama area can also be found in Brown's memorandum. The suggested management strategy assumed a federally-managed area stretching from Crane Lake to and including the Kabetogama Peninsula, and recommended the national park formula for development. It stressed the importance of limiting access to just two sites—Crane Lake and Kabetogama Lake—and proposed a development and interpretation strategy that would "encourage leisurely enjoyment by water and by trails...arrive by car, park it, and lock it up." [53] Finally it envisioned an area that would fill the recreational opportunity gap between the wilderness experience of the canoe country to the east and many commercially developed lake areas in northeastern Minnesota.

In retrospect, Brown's report is important because it reveals the very earliest thinking of the NPS planners regarding the following subjects so important in shaping final proposals for Voyageurs National Park: The Kabetogama area's physical and cultural amenities; its strategic position in the emerging federal recreation corridor along the Minnesota-Ontario border; its potential as a "recreational alternative" in the region and the state; and the uncertainty of park planners regarding its categorical place as a unit in the National Park System. It would be almost two years before the NPS shared many of these issues and concepts with the general public.

On June 28, 1962, the International Falls Daily Journal carried a front-page report on the Kabetogama trip hosted by Governor Andersen for Director Wirth and other NPS and state officials. This was the first official public acknowledgement that state and federal officials were seriously interested in seeing the area become a national park. The article included excerpts from a press release written by Governor Andersen in which he announced, "consensus" of opinion that the Kabetogama Peninsula was an enormous recreational resource to a great degree still in its natural state. "It should be made available for use by more people while preserving its wilderness character for posterity." [54] In making this statement and on other occasions, Governor Andersen never hesitated to express his respect for and confidence in the professional expertise of the NPS. [55] The Andersen statement also noted that a national park in the Kabetogama area would add historical, recreational, and wilderness values not then represented in the National Park System. Recognizing the area's strong ties to the French voyageurs and the fur trading era, the statement concluded with a suggestion, generally attributed to Sigurd Olson, that the park be called "Voyageurs Waterways National Park" and that federal, state, and private parties, "should cooperate in detailed and comprehensive studies to determine whether a national park should be established in this area." [56]

National Park Service planners were preparing for comprehensive studies in the Kabetogama area even as Governor Andersen and his guests were enjoying the beautiful scenery on Rainy and Kabetogama Lakes. On June 28, one day after the excursion led by Governor Andersen, NPS Director Wirth, Midwest Regional Director Baker, and Sigurd Olson flew over the entire border lakes region. What they saw convinced Baker and Wirth of what Olson and others on the Quetico-Superior Council had maintained for years—that the "entire complex of the Voyageurs Waterway from the Northwest Angle to Grand Portage should be tied together through a coordinated program..." [57] This meant, of course, public control of much of the area with federal agencies having jurisdiction over the border waterway region from International Falls to Lake Superior.

The study team from the Midwest Regional Office of the NPS worked in the Crane Lake to International Falls area from July 30 to August 10, 1962. For part of that time Minnesota State Forest division people and K.W. Udd, a staff person from the Superior National Forest office in Duluth, accompanied them. Udd was invited because much of the study area from Crane Lake to Kabetogama Lake fell within what was officially designated a National Forest Purchase Unit. Udd said that the National Forest Reservation Commission in 1956 authorized this unit with prospects for formal inclusion within Superior National Forest at a later date. An earlier state policy opposing expansion of Superior, had been set aside and considerable acreage within the purchase unit had already been acquired through trades and purchase agreements with the state and Superior National Forest.

In late summer of 1962, personnel at Superior National Forest fully expected that the westerly boundary of the forest would soon be extended to include these lands. Upon returning from his trip with the NPS study team, Udd prepared a report which noted that the NPS was not confining its study to the Kabetogama area but had expanded its range to include lands already in Superior and other potential USFS lands as well.

Udd's report regarding the geographic extent of the NPS study alarmed USFS personnel and especially George James, the regional forester in Milwaukee. James immediately expressed his concern in a letter to the NPS's Midwest Regional Director in Omaha. In his letter he said, "I was under the impression that this area of interest [National Park Service interest] was outside the adjusted National Forest Purchase Unit boundary west of Crane Lake...We are surprised and perturbed to now learn that the study under way at the present time includes a portion of the area already within this adjusted National Forest Purchase Unit boundary extending down to and including the Crane Lake area." [58] He went on to say that the Development Program for the National Forests sent to Congress and the president in 1961 clearly spelled out USFS concerns for the protection, public use, and recreation environment of lands managed by the USFS. He closed by asking for a meeting with NPS staff before they scheduled any further work in the Crane-Namakan Lakes area. [59]

Regional Director Baker informed Director Wirth of the conflict with the USFS and suggested an NPS response that would urge extension of the boundaries of Superior National Forest into the Crane-Namakan area, "be delayed until the study is completed and there is then the opportunity to weigh the several resource use potentials against the overall public interest." [60] Perhaps looking for some assistance from a neutral party in arbitrating this matter, the Baker letter further noted, "Since this area involves federal interests crossing departmental lines as well as state and local interests, it appears to fall within the sphere of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR)." [61] Newly established in April 1962 as a coordinating agency, the BOR played a minor role in the formulation of plans for Voyageurs and no significant role in dealing with the interagency squabble over USFS lands in the initial NPS proposal for Voyageurs.

Developments in the fall of 1962 quickly revealed that the USFS would have nothing to do with a delay in extending the boundaries of Superior National Forest to include the Namakan-Crane Lakes area. Instead they began to plan an offensive to protect what they felt were their legitimate rights and interests in the area. Historically the creation or extension of national parks often ate into surrounding national forests, and the proposal for Voyageurs was seen as no exception. To the USFS, this proposal if adopted, would represent yet another violation by the NPS of the territorial integrity of a national forest. The staff at Superior National Forest realized they would have to move rapidly if they were to prevent such an incursion into the Superior.

Ironically, just as they prepared to do battle with the NPS and defend their interests in the Crane-Namakan area, they learned that at its fall meeting in Hawaii, the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historical Sites, Buildings and Memorials (Advisory Board) had voted to submit a formal recommendation to the Secretary of the Interior Advisory Board in which it noted that the Crane Lake-Rainy Lake region was, "superbly qualified to be designated the second national park in the Midwest." [62] (Isle Royale in Lake Superior, became the first national park in the Midwest when it was authorized in 1931.)

|

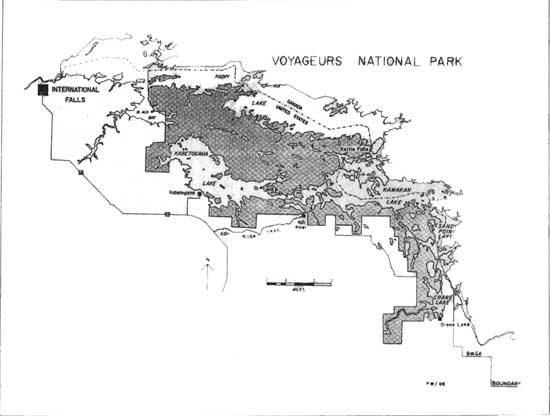

| Figure 5: First Proposal for Voyageurs National Park, 1963. (click on image for a PDF version) |

In language that clearly captured one of the fundamental objectives of the Quetico-Superior Council more than thirty years before, as well as describing a remarkable and strategic opportunity for the NPS, the Advisory Board declared, "With Grand Portage National Monument at the gateway of the region, 200 miles to the east, and a National Park at the West Entrance, the two areas of the National Park System would hold between them the Boundary Waters Canoe Area of the Superior National Forest and the adjacent Quetico Provincial Park of Canada. They would stand as inviolate bastions at either end and give added protection and significance to the entire complex of waterways on both sides of the border." [63]

The Advisory Board's recommendation on Voyageurs came after considering Director Wirth's report to them on NPS studies of the entire Minnesota-Ontario border waterways. Wirth's report emphasized the more detailed study of the Kabetogama Peninsula and Crane-Namakan Lakes area that the NPS was now advocating as the site of a new national park. (A policy decision had apparently been made late that summer to drop reference to the site as a "national area" and call it a "proposed national park.") Governor Andersen and Sigurd Olson had made it very clear that they would only support a national park proposal. It is interesting to note that in what must have been a departure from normal procedure, the Advisory Board made its recommendation in the absence of a completed draft proposal. That proposal was still in preparation and would not be ready until March 1963. It is quite possible that the Advisory Board was aware of the pending westerly extension of Superior National Forest's official boundary to include the Namakan-Crane area, and they wished to get their position on the record before that event occurred.

Another boost to the Voyageurs cause came from Governor Andersen in a speech at the Rex Hotel in International Falls on September 19, 1962. In a story reported the following day in the International Falls Daily Journal, the governor, who was campaigning for reelection and traveling with a Republican state candidate's caravan, gave a progress report on the national park proposal.

Apparently unaware of the deepening rift between the two agencies over the NPS intent to include the Namakan-Crane area in its proposal, Governor Andersen said that the two agencies were working together to, "get a plan going for the Forest Service to exchange land with the National Park Service." [64] He said that consolidating land ownership was a necessary first step in securing a national park for Minnesota. Following that would come NPS recommendations to the National Parks Advisory Board, which in turn would recommend to the secretary of the Department of the Interior, and then to Congress for authorization.

In fairness to the governor, it would have been impossible to provide details relative to the process for gaining approval of a national park proposal in a brief campaign speech. Nevertheless, it does give some insight as to the ideal path to final approval that many supporters had in mind when the park idea was first presented. For some, what transpired over the next few years to distort that path was wholly unexpected.

As November 1962 began, the NPS could take a measure of satisfaction that their recommendation for a national park along the border lakes region from Rainy Lake to Crane Lake had the strong support of the governor of Minnesota, the Minnesota Department of Conservation, some prominent conservationists in the region, and the recommendation of the National Parks Advisory Board. However, any hopes for early congressional action on their proposal were diminished by three events that occurred before the year was out.

The first of these events was Elmer Andersen's defeat for reelection to a four-year term as governor. The race between Andersen and Democrat Karl Rolvaag was so close that a statewide recount was ordered—a procedure that took nearly five months. Rolvaag was eventually declared the winner in March 1963. [65] Although both candidates favored the establishment of a park at Kabetogama, Governor Andersen's support was predicated on first-hand knowledge of the natural resources of the region, its cultural significance, and the firm conviction that its preservation was in the national interest. [66] Losing his bid for reelection was truly a serious blow to the park cause. It meant that Andersen no longer had the power of the governor's office in his quest for a national park and was required to continue his efforts on behalf of the park cause as a private citizen. He assumed a leadership role in the movement for park status and for the next seven years worked tirelessly for authorizing legislation. Without his organizational skill, his ability to energize park advocates during the long campaign, and his dedication and enthusiasm over the ensuing eight years, there would be no Voyageurs National Park today.

The second event that worked against speedy authorization for Voyageurs was the emergence of determined USFS opposition to the relinquishing of lands in the Namakan-Crane Lakes area to the NPS. This became apparent during a November 15, 1962 meeting in Duluth attended by NPS and USFS personnel along with the commissioner of conservation and the state parks director for Minnesota. This was the meeting George James had asked for in late August. During this conference, NPS Assistant Midwest Regional Director Chester Brown presented the NPS plan for the entire border lakes region. The proposal included the Namakan-Crane Lakes area in a proposed national park stretching from near International Falls on Rainy Lake to Crane Lake.

L.P. Neff, supervisor for Superior National Forest, responded by noting that the Namakan-Crane Lakes section was already appropriately managed by the USFS and saw no reason for its inclusion in the proposed national park. Neff's position, of course, was contrary to Brown's position, which was that the entire stretch of the proposed park be managed by a single agency. As the meeting broke up, Brown asked the USFS to send him their management plan for the Namakan-Crane Lakes segment so that it could be appended to the NPS report on Voyageurs, which would be completed in early 1963. [67]

In the weeks following the November 15 meeting, the USFS went on the offensive to protect what it felt were its legitimate interests and mandate in the Namakan-Crane Lakes area. Historically, the creation or expansion of national parks frequently ate into existing national forests, and the proposed Voyageurs National Park, as initially planned, would represent yet another violation by the NPS of the territorial integrity of a national forest. [68] Forest Supervisor Neff and his staff were determined to retain control of their holdings in the Namakan Crane Lakes area by countering with a recreation plan of their own. In a letter to the regional forester, Neff emphasized that the fight to retain the Namakan to Crane Lake area under USFS management would be difficult mainly because of the lack of USFS development. He proposed an aggressive course of action, including reordering budget and planning priorities so as to complete a five-year development plan as soon as possible and to put administrative personnel in the area no later than May 1, 1963. He further urged the USFS to "do everything possible to have the unit proclaimed as part of the National Forest as soon as possible." [69]

Neff's position was supported by the report of a special task force assigned to look into the matter. The task force leader said that moving the forest boundary westward, to include Namakan-Crane Lake, would be the "most positive action that could be taken to strengthen our position." (He also suggested that the BOR be called in to review the proposal given the conflict between the two federal agencies rather than "letting the National Park Service roll along with their proposal.") And, because the largest landowner in the proposed area was the M&O Paper Company, he suggested contacting M&O to remind them of the "long-term future prospects of what might happen to this entire stretch of country with respect to future availability of timber products and that the national position of the wood industry has generally been to disfavor further extensions of federal ownership and reductions in areas available for multiple use management." [70]

The file copy of the task force report found in Superior National Forest office files, had the following handwritten comment that actually became the official position of the USFS regarding the NPS proposal for Voyageurs. "I think we cannot afford to be 'against' a national park in Minnesota and I think we should go slow in attempting to scotch the Kabetogama proposal. Believe our best bet is to hold fast to our line at Junction Bay on Namakan and stand on our management of this area." [71]

Anticipating early presidential action on westward extension of the forest boundary to include the Namakan-Crane Lake segment, Neff's call for quick action on a recreation and management plan was approved at the regional level and rushed to completion in early 1963. It was a hastily prepared document that included several new roads providing two access points to the south shore of Namakan Lake and another to the northwest of Crane Lake. [72] Such road penetration was just the opposite of the NPS plan to develop a water-based park with highway access at only four locations throughout the entire park. [73] Nevertheless, the commitment and energy displayed in preparing the plan served notice that the USFS had no intention of giving up their claim to the Namakan-Crane Lakes area.

Forest Supervisor Neff and his staff didn't have to wait long for federal action on expansion of Superior National Forest. On December 28, 1962, President Kennedy signed the executive order incorporating the Kabetogama Purchase Unit (Namakan to Crane Lake) within the official boundaries of Superior National Forest. This action produced yet a third major obstacle to quick action on the NPS proposal for Voyageurs. The Namakan-Crane Lake segment, now securely within the forest, could be included in future planning. Through this action, USFS officials had already realized their principle objective, which was so clearly stated in November by Neff and again in early December by Bacon, the task force leader—get official action on the boundary extension as soon as possible!

Sometime in mid-1963, the USFS abandoned its hastily prepared Namakan management recreation plan in favor of one more sensitive to the wilderness character of the region. This plan, entitled, "The Crane Lake Recreation Area," stressed the primitive nature of the unit, expressly prohibited public roads or the use of motorized vehicles, and encouraged the use of power boats as the principle means of access to scenic areas and prime fishing locations. [74] In fact, the overall recreational objectives of this revised plan were essentially the same as those proposed by the NPS for the same area as part of its proposal for Voyageurs.

This correlation with the NPS plan was deliberate. The USFS was determined that higher officials and eventually, the general public, see their proposal for the Namakan-Crane Lake area as one that effectively complemented the NPS plans for the unit, thus making it unnecessary to include it within the proposed park boundaries. [75] This determination to hold fast to the newly won addition to Superior National Forest became all too apparent to the NPS and Voyageurs proponents during the first months of 1963.

Governor Andersen, concerned that the vote recount may go against him, sought to move the park proposal forward while he still retained the power of the governor's office. In January, he asked his conservation commissioner to contact the regional offices of the NPS and USFS regarding progress on USFS land transfers that were required to meet the recommendation of the NPS proposal for Voyageurs. Andersen realized that given the mix of land ownership in the proposed park, timely resolution of the land exchange and transfer questions would greatly facilitate early authorization of Voyageurs. Unfortunately, Mr. Andersen was not encouraged by the responses to Commissioner Prout's queries. [76]

Having stated their positions at the November 15 meeting in Duluth, the two agencies proceeded to follow paths consistent with those positions. The USFS began the new year with the Namakan-Crane Lakes segment now solidly within the boundaries of the Superior National Forest, and the NPS continued to work toward completion of its draft proposal for Voyageurs hoping to get some accommodation from the USFS so that they could include the unit in their plan. However, their task was made far more complicated by an interagency agreement made on January 28, 1963.

Debate centering on the establishment of a new national park seldom takes place without reference to past issues or controversies involving similar circumstances or questions of policy. Voyageurs National Park was no exception. At the time planning began for Voyageurs, serious disagreements over management jurisdiction between the NPS and USFS were occurring in the Cascade Mountain region of Washington state. A bitter interagency wrangle had developed over USFS territory proposed for a North Cascades National Park. Such disagreements were of course, not new, but they were inevitably confusing to the public which found it hard to understand how two agencies, who were both charged with the responsibility of managing and protecting public lands could engage in such acrimonious jurisdictional disputes. Because these "family" squabbles were also proving embarrassing to the Kennedy administration, something had to be done.

So it was in the course of the debate over North Cascades National Park that the top administrators in the two affected departments came forward with an agreement that they believed would alleviate the situation. On January 28, 1963, the secretaries of the Department of Agriculture and the Department of the Interior sent a letter to President Kennedy that spelled out their agreement. The press quickly dubbed the agreement the "Treaty of the Potomac." In the secretaries' statement to the president they said, "Neither department will initiate unilaterally new proposals to change the status of lands under the jurisdiction of the other department. Independent studies by one department of lands administered by the other will not be carried on. Joint studies will be the rule." [77]

When Judge Hella received a copy of the agreement, he wrote to Sigurd Olson noting his disappointment with the accord. "It, in fact, entrenches the Forest Service more firmly in the recreation business in a major way and at the expense of the National Park Service. Obviously, the Kabetogama proposal will now end up as a recreation area under the dual administration of the two services." [78] In his reply, Sigurd Olson, who was very close to policy makers in the NPS, said, "The National Park Service has no intention of giving up its hopes for a Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota. It may be necessary to whittle down our acreage some, but it also may be possible in view of the agreement between Agriculture and Interior to work something out. I do not intend to go for any joint recreational area and I am sure no one else feels otherwise, including Governor Andersen." [79]

Governor Andersen, continuing his quest for specifics on the status of the Voyageurs proposal, asked key administrators from the two federal agencies to meet with him and his conservation department staff on February 8, 1963, in St. Paul. What he learned was certainly not encouraging. Regional Director Howard Baker explained the NPS proposal using a map that showed the proposed park extending from Black Bay on Rainy Lake to the mouth of the Vermilion River at the south end of Crane Lake. [80] USFS Regional Forester George James took exception to the inclusion of the Namakan-Crane Lakes area in the proposal and proceeded to reaffirm the USFS stand against any intrusion into Superior National Forest. [81] He also stated that there could be no discussion of land exchanges until legislation authorizing the park clearly defined its boundaries. (This reference to land exchanges pertained to scattered parcels of USFS land on the Kabetogama Peninsula.) James knew well that the USFS position had been strengthened by the recent executive order extending Superior's western boundary and also by the "Treaty of the Potomac" that was aimed at avoiding jurisdictional disputes involving competing recreational management proposals.

Andersen expressed irritation that the USFS boundary adjustment was made without his being informed. Then, addressing both parties, he stated that his primary objective was to secure a proper national park for Minnesota and that in pursuing that goal the national interest should prevail over agency objectives. [82] But as the meeting progressed, he could see that the USFS would not budge on the Namakan-Crane Lake area, and so the governor turned to Baker and suggested that they (the National Park Service) accept a "compromised" area if Minnesota was to get a national park. Baker replied, "In order to propose an adequate national park we must include the Namakan-Crane areas." [83] He also said that the Advisory Board had already endorsed the proposal with the Namakan-Crane Lake segment included, and he felt compelled to submit the full proposal in its first draft to NPS Director Wirth on March 1. [84]

This report, entitled, The Voyageurs Route and a Proposed Voyageurs National Park was circulated internally at the NPS, and copies were sent to the USFS and state officials in Minnesota. It dealt with the entire border area from Lake Superior to the Northwest Angle and contained a special section proposing a Voyageurs National Park. That section included USFS lands in the Namakan Crane Lake area thereby fulfilling Baker's strongly felt obligation to present the full report. The USFS predictably objected to that part of the NPS proposal that incorporated USFS land within its proposed boundaries.

The interagency squabble as to how to present the Namakan-Crane Lake area in the official Voyageurs proposal was kept in-house except for the governor, some top staff people at the state level, and a few Minnesota conservationists, most notably Sigurd Olson. In the absence of public knowledge about the proposed park, rumors and distortions about Voyageurs began to circulate in the International Falls area. The delay certainly did not help Governor Andersen in his quest for something substantial that he could carry to the public for their support.

In International Falls, local businessman Wayne Judy, an early and staunch supporter of a national park for the border area, became concerned over ill-founded rumors and local misunderstandings about the park and expressed these concerns in a letter to Judge Hella in St. Paul. He asked the governor and NPS people to meet in International Falls in late April and conduct a public information meeting. [85] (Unfortunately for Mr. Judy, other park supporters, and the citizens of the International Falls area, more than one and one-half years would pass before such a meeting ever took place.)

Meanwhile, Governor Andersen and others close to the issue sought to resolve the differences between the two federal agencies. Andersen, miffed by the slow pace of events and possibly facing defeat in the voting recount, tried his hand at speeding things up. He knew that the untimely extension of Superior's boundaries and the subsequent jurisdictional dispute over the Namakan to Crane Lake area could go on for many months. He therefore decided to work through the NPS for a solution. Early in March he called Director Wirth and repeated the suggestion he had made to Howard Baker at the February 8 meeting in his office. He suggested to Wirth that the NPS, "Try to reduce the dimensions of the proposed park to the limits of the Kabetogama Peninsula." [86]

Unmistakable evidence that the USFS was not going to budge on the Crane Lake issue was contained in a late March letter to Wirth from the USFS Chief Edward P. Cliff. Cliff said that it was his understanding that the NPS proposal for Voyageurs would include the Kabetogama Peninsula and adjacent lands. He endorsed that proposal and stated that the USFS would cooperate by transferring any USFS lands in that area to accommodate the NPS and its proposal for Voyageurs National Park. But any lands east of that were in Superior National Forest. In the same letter the chief forester explained that the USFS would be developing a management plan for the Namakan-Crane Lake area that would "complement" the proposed national park at Kabetogama. [87]

Before the end of March a meeting was held in Washington to discuss the impasse over inclusion of the Namakan-Crane Lake segment in the Voyageurs proposal. Attending the meeting were personnel from the Bureau of Reclamation, NPS, USFS, and Sigurd Olson from Minnesota. In a letter to Interior Secretary Stewart Udall summarizing the results of the meeting, Olson said it was decided to "go ahead with the park proposal for the reduced area, and that in any legislation drafted, should be a statutory provision for a joint study of the controversial area." [88] Given the USFS intransigence on the Namakan-Crane Lake issue and pressure from prominent supporters in Minnesota, the NPS felt compelled to prepare a revision of the preliminary draft that would seek to comply with the provisions of the "Treaty of the Potomac," which required joint studies in such cases, and also mollify the USFS.

In a revision dated September 1963 and again circulated in-house, the NPS recommended that, the "Namakan-Crane Lake area within Superior National Forest containing scenic and natural values of national significance be designated a study area to be jointly studied by the USFS and NPS to determine the most practical means of assuring that the values found in this area are adequately preserved in the public interest." [89] Park advocates in Minnesota considered this proposal a compromise position. But advocates, including Sigurd Olson, who personally advanced it in a letter to Udall in May 1963, reluctantly supported the compromise. [90]

In his letter, Olson recommended going ahead with a park proposal that identified a reduced area (Kabetogama Peninsula) and that authorizing legislation should contain a provision for a joint study of the controversial area. Olson believed that a required future joint study of the contested area would lead to preservation management policies close to or the same as those that the NPS would develop for a national park on Kabetogama. But his very close identification with the initial planning for a Crane Lake to Rainy Lake Voyageurs National Park revealed his strong preference for the concept of a single-agency administration. He wanted NPS officials to stress the physical unity of the "voyageurs highway" in the revised report and even wrote the introduction to the report incorporating the unity theme and the need to complete the protective pattern for the voyageurs route along Minnesota's border lakes region. [91]

For its part, the USFS was no doubt pleased to see that the revised draft for Voyageurs excluded the Namakan-Crane Lake section. However, they took exception to the joint study recommendation, and they were offended by the claim implied in the request for a joint study that the USFS management would not adequately protect and preserve the scenic resources of the area. Therefore, in its final draft, released to the public in September 1964, the NPS removed the offending implication regarding USFS management standards and softened the language recommending a joint study. [92] Even this language bothered the USFS. The official USFS response to the NPS was contained in a letter from the Chief Forester Edward Cliff to NPS Director Wirth just before the report was released to the public. In his letter he expressed the opinion that reference to a joint study was unnecessary and then noted his preference for cooperation on an informal basis regarding the management strategies for the Namakan-Crane Lake area. He also objected to maps in the report that highlighted the proposed study area. [93]

The NPS addressed the chief forester's concerns in a revision to the 1964 report that was dated September 1965. [94] Although this 1965 report was never formally produced for public use, it did reveal a revision in national park policy—complete abandonment of the notion that it might someday become a part of Voyageurs National Park or an area jointly managed with the USFS. Future reports on Voyageurs would show a park restricted to the Kabetogama Peninsula and the adjacent lakes, Kabetogama and Rainy.

Over two years had passed since Governor Andersen had written his statement announcing NPS intentions to do detailed field studies for a proposed Voyageurs National Park. The 1964 report described a much smaller and, according to some park professionals, a less meaningful park than originally envisioned. The general public was never aware of the maneuvering that took place between the two federal agencies over the disposition of the Namakan-Crane Lake segment. For the next five years all of the literature, audio-visual material, and speeches devoted to the promotion of the park proposal carefully excluded any reference to the area southeast of the Kabetogama Peninsula. The USFS continued to develop its plans for the "Crane Lake Recreation Area" and the official position of the NPS was to work for the establishment of a national park whose territory lay wholly outside the boundaries of Superior National Forest. [95]

The NPS pullback over the Namakan-Crane Lake issue was clearly a victory for the USFS. Unlike similar situations in the west, the USFS in this instance was able to prevent the transfer of lands for the purpose of achieving an NPS objective. The only way the NPS could restore this territory to its original proposal would be through congressional legislation. The delays between 1962 and 1964 proved costly to any hopes for quick approval of a Voyageurs National Park.

There is no question that pulling the Namakan-Crane Lake area out of the proposed park boundary troubled park professionals and supporters who were best acquainted with the area. Some, like Judge Hella, director of state parks, feared that removal of Namakan-Crane Lake area weakened the proposal for Voyageurs and that the NPS might even settle for a national recreation area. In a memorandum to the conservation commissioner, he stated, "I doubt that Kabetogama Peninsula by itself will qualify as a National Park and I believe that we would have little to gain if it were established as a National Recreation Area—a National Recreation Area would command no more attention than would a major State Park in this region." [96] Hella's concerns turned out to be prophetic as public debate over Voyageurs progressed during the 1960s. The concept of a national recreation area as a more logical management strategy for Voyageurs was frequently offered by public officials at both the local and national level, and it would always be vehemently opposed by leading advocates for the park.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

voya/legislative_history/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 23-Jan-2009