|

TUMACACORI

Tumacacori's Yesterdays |

|

JESUIT PIONEERING

On the extreme northern part of New Spain was a large. rugged and dangerous area which came to be known as Pimeria Alta (Land of the Upper Pimas). This land included much of what is now northern Sonora, and all of what is now southern Arizona, save for the territory east of the San Pedro River. It was bounded on the north by the Gila River, on the south by the Altar River Valley, and on the west by the Colorado River and the Gulf of California, and to the east by the San Pedro River Valley.

This was a land of ragged mountains and rocky and barren deserts, slit here and there by fertile and well watered valleys. Over the hill and mountain country of the northeastern portion roamed the nomadic and fierce Apaches, while to the southwestward were the almost equally fierce Seri Indians. In the valley bottoms were numerous villages of sedentary agricultural peoples, who were essentially of a peaceful disposition. They consisted mainly of the Papagos, Pimas, and Sobaipuris, all with a common basic language and culture, and supposedly the same ancestral stock.

|

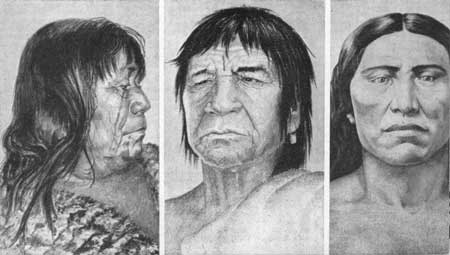

| Pima woman, Papago man, and a typical Apache man, right. |

The Santa Cruz River, lying west of the San Pedro, starts on the oak-clad western flank of the Huachuca (Wah-CHOO-kuh) Mountains, wanders southward for several miles into what is now Mexico, slowly veers westward, and then, having made up its mind, returns to Arizona, flowing northward east of Nogales and close by Tumacacori, to be lost in the sands before it reaches its apparent destination, the great valley of the Gila River.

Above the floor of the Santa Cruz the rocky foothills support a rich growth of cactus and Ocotillo, pushing upward into Oak clumps and the craggy rocks of the mountains, which spread their long and knobby arms on either side of the river's course.

|

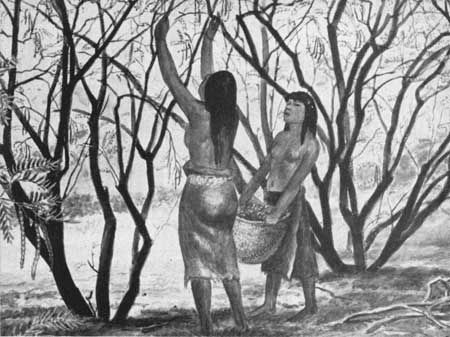

| Pima gathering mesquite beans, upper, and maize farming, lower. |

|

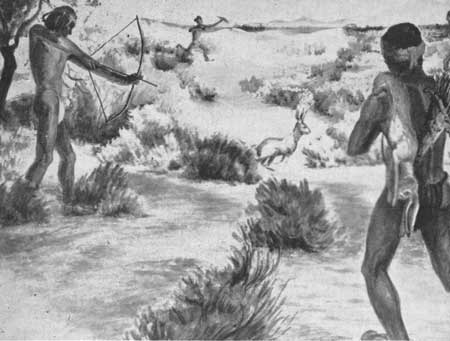

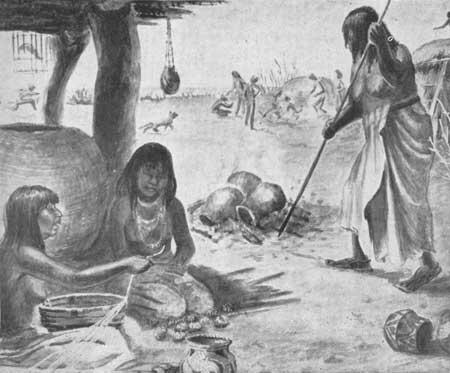

| Pima rabbit hunting, above, and making of pottery and basketry, below. |

Two hundred and sixty years ago there were several stretches along the Santa Cruz where the water ran the year around. Along its banks grew great groves of Cottonwoods and Mexican Elders. The river flats, in the lower places, supported thickets of grass and Sunflowers, and a little higher, feathery forests of Mesquite and Catclaw. It was on the flats that the Indians who lived here managed to grow their crops of corn, squash, beans, and cotton. By small dams and short ditches they could irrigate, and could build their houses close at hand, perhaps in the shade of the larger Mesquite trees close above their fields. Little is known of these people in prehistoric times, except that they did farm these crops, and lived in what must have been wattle-and-daub huts, generally gathered in clusters or villages. Apparently Tumacacori [1] was originally a Pima town, although later in Spanish times it contained a number of Papagos as well, and possibly some Sobaipuris.

On a day in January of 1691, some of the headmen of Tumacacori, in company with other men of influence from the much larger town of Bac (later San Xavier del Bac), entered the pages of history. For some time they had been hearing of the mission work of the white-skinned Europeans to the south, and especially of one man called Padre Kino, who wore a black robe and feared nothing, perhaps because he carried some shiny crossed sticks which warded off all evil. This man talked often with a strange God, and had a faculty for making friends with strange people. There was curiosity about him, and his power, and especially about the fruit trees, the wheat, and the livestock which he was reported to be giving away to the Indians.

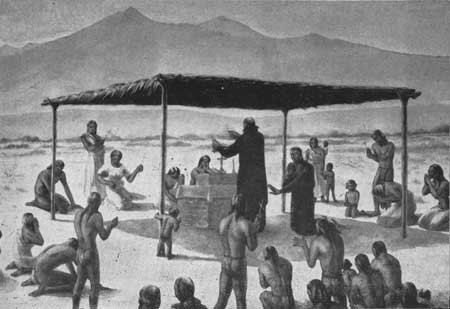

|

| As Father Kino might have looked saying Mass in the ramada at Tumacacori in 1691. (Illustration in the Monument Museum) |

The group decided the padre must be invited to come among them. So at Tumacacori they proceeded to construct a suitable guest house. They built a little shelter for him to sleep m, and one to use for a kitchen. And because they had heard that he liked to talk to his God in a special place, they made a shelter of poles with a roof over them (ramada) where he could pray. Lastly, they made some crosses. Although the crosses might not make strong medicine like those of Father Kino, they should impress him with good intentions. Then a group set forth, southwestward from the Santa Cruz Valley, up over the hills away from the river, across the divide into the Altar Valley drainage, toward the town of Tucubavia.

|

| Terrain near the site of the Dolores mission, Sonora, Mexico |

Let us introduce you to this priest. Eusebio Francisco Kino, born in Segno, Italy, in 1645, educated in Bavaria, Italy and Spain, was sent as a Jesuit missionary to Mexico in 1683. From that year to 1687 he worked to establish missions among the Indians of Lower California. Upon the temporary failure of colonizing efforts there he was transferred, in February, 1687, to Pimeria Alta, to be rector of the Indians in this vast area. On the southern fringe of this virtually unknown land, Kino established the mission of Nuestra Senora de los Dolores, near Indian town of Cosari. This was to be his headquarters for the remaining 24 years of his life.

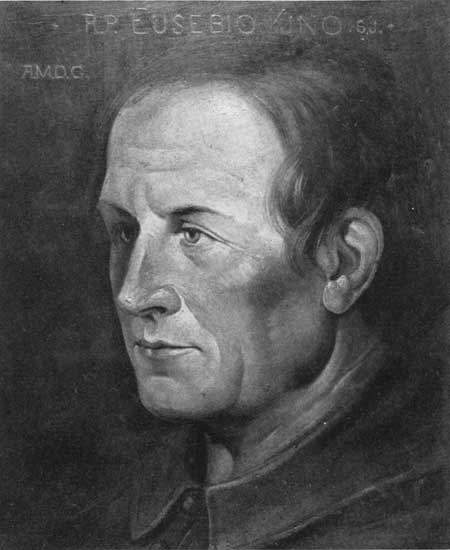

|

| Artist's conception of Father Eusebio Francisco Kino (Museum illustration) |

Kino was a man of great natural abilities, combined with zeal and enthusiasm. His character welded the contasting elements of consuming religious fervor with a very down-to-earth practicality. Single-heartedly devoted to the conversion of the Indians and the saving of their souls, he knew that religious teaching was more readily heard by primitives when their stomachs were full. So he introduced cattle and wheat and fruit trees, and taught the natives how to realize the fullest value from them. This exerted a tremendous effect on the domestic economy of his region, gaining for him many supporters and friends.

With his prestige at a high point as he travelled on horseback through his uncharted domain, he achieved great success in gaining conversions and in persuading the Indians to give the work necessary toward construction of churches. By 1691 he had already established a chain of missions along the Altar and Magdalena rivers in Sonora. At several of these, mission churches had either been built or were in process. Early in January of this year, while visiting the Indian village of Tucubavia, in company with the Father Visitor, Juan Maria de Salvatierra, a significant meeting occurred.

Quoting Father Kino: "It was our intention to turn back from El Tucubavia to Cocospera, but from the north some messengers or couriers of the Sobaipuris of San Xavier del Bac, more than 40 leagues' journey, and from San Cayetano del Tumagacori [2], came to meet us, with some crosses, which they gave us, kneeling with great veneration, and asking us on behalf of all their people to go to their rancherias also. The father Visitor said to me that those crosses which they carried were tongues that spoke volumes and with great force, and that we could not fail to go where by means of them they called us."

Accordingly, the two priests followed their new friends to the north, and arrived at the rancheria of Tumacacori, which at that time consisted of more than 40 rather closely spaced houses. Here they conferred with the Tumacacori headmen, said Mass, and baptized some infants. The seeds of Christianity had been sown in southern Arizona!

After this visit the two fathers returned southward, and it was not until late summer of the next year that Kino again came to Tumacacori, and rode 40 miles northward to make his first visit to the town of Bac. Here was a populace numbering about 800 people. After a cordial welcome, he passed on to the northeast into the San Pedro Valley, to meet other friendly, though less docile, Sobaipuris.

But our story is concerned principally with Tumacacori. Although Father Kino wanted to give the village a resident priest, and to build a mission church here, such was not to be for a long time. It was very difficult to obtain funds for sending additional priests into this remote frontier. So Tumacacori was established simply as a "visita" or place of call, to which Kino and later Jesuit missionaries came for occasional visits and services as opportunity arose.

|

| Father Kino on one of his many horseback trips, as portrayed in a diorama in the Tumacacori museum. |

In 1695 Kino commented that at Tumacacori were sheep and goats, and that there were fields of wheat and maize. Maize, or corn, was native, but wheat and livestock were introduced. He also mentioned that there were earth-roofed houses of adobe, which is our first indication that the natives were beginning to use adobe bricks for house construction.

Two years later we find our first census of Tumacacori, made by Captain Cristobal Martin Bernal. He counted 117 persons, living in 23 houses( [3]. In this year he visited the Sobaipuri villages at Kino's request, to see how peaceful these folk were. Incidentally, while on the San Pedro River the two men found some of the "peaceful" Sobaipuris having a scalp dance, after having killed a number of their deadly enemies, the Apaches. This did not break the Captain's heart, for the Apaches were a constant menace to Spain's northern New World frontier. In the same year Kino traveled to Tumacacori and San Xavier to leave "ganado mayor" (larger livestock, presumably cattle) so that by multiplying they would serve to sustain the Indians, and the missionaries who were expected. A year later there were 74 cattle at Tumacacori, which was one indication that today's great southern Arizona cattle industry was by then well started.

In March of 1699 Lieutenant Juan Matheo Manje (who had been delegated by the alcalde mayor of Sonora to accompany Kino on many of his trips) made an interesting entry in his diary. While he and Father Kino were returning from a trip to the Gila River, the padre became ill from a drenching received in a terrible storm. When they came along the west bank of the Santa Cruz River, opposite the village of Tumacaconi, the river was so high they were unable to cross it. The Indians then obligingly brought mutton across the torrent to make a stew for the sick man. That must have been a rugged crossing, and a real act of devotion!

Since the town apparently was, at the time of this entry, on the east bank, we are curious as to when it was moved across the river. It must have been on the west side long before construction began on the present church, but we can find no reference to the move.

In October of this same year Kino records, "We slept in the earth-roofed adobe house, in which I said Mass the following day." We believe this to be the "adobe chapel" referred to by later writers, and that it was the only "church" at Tumacacori in Kino' s time.

Finally, in 1701, Kino succeeded in having four missionaries assigned to Pimeria Alta. Among these was Father Juan de San Martin, who was assigned as his resident station the rancheria of Guevavi, about 15 miles upstream and southeast of Tumacacori, with Bacoancos and Tumacacori as visitas. At Guevavi they built a small house and church in the next few months, and laid the foundations of a more pretentious church and a large house. Unfortunately, Father Juan's stay was very brief, for by 1704 we find he was at work near Hermosillo.

In a report for 1706 Kino informs the Father Provincial of nine pueblos which "we three fathers . . . are actually administering." This list does not include Guevavi and its visitas, which of course means that Tumacacori was no longer receiving regular visits from a priest. Kino also asked for new missionaries, but did not seek a replacement for Guevavi. He did ask for priests for a mission at Santa Maria de Suamca, a few miles southeast of Guevavi, and for the rancheria of Quiburi, to the eastward on the San Pedro, where lived some very staunch Apache-fighters and allies. We forgive him for overlooking our neighborhood at this time, for we suspect he was finding the Apaches plenty of trouble, and had to plan limited missionary help for more strategic positions on the Apache frontier.

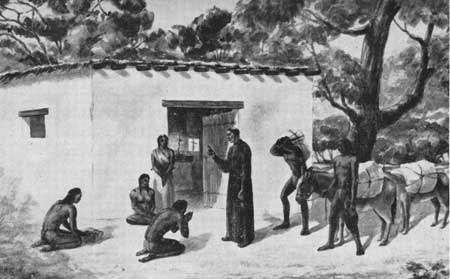

|

| Museum illustration of Father Kino blessing Indians in front of the adobe house in which he said Mass in 1699. |

During the balance of his life no new missionary came to work in what is now southern Arizona, and Kino labored alone in this area, visiting the people as often as opportunity arose. His last days were filled with disappointment, for he was unable to get any help, just promises. Spain was up to her neck in war, England was chopping away at her colonial frontiers in other areas, and other frontiers were considered more necessary for expenditure of priests and soldiers than Pimeria Alta.

Kino died in 1711, while dedicating a new chapel in Magdalena, and was buried under the chapel floor there by his loyal co-worker, Father Agustin Campos.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

jackson/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2007