|

NEW RIVER GORGE

PROCEEDINGS New River Symposium 1984 |

|

LIFE ON THE NEW RIVER FIFTY YEARS AGO

Murray Shuff

In the fall of 1983, on a sunny Sunday afternoon, I made a journey to the site of what was once a small coal mining community in West Virginia. It was to be a special journey for me, because I was returning to the banks of the New River to visit the town of my youth—Stone Cliff. I had lived there, in the town of Stone Cliff, from 1930 to 1938, and, during those eight years, I was very much a part of . . .

As I parked my car and walked back across the bridge above the New River, it was with a sense of anticipation. I knew the town had long since been abandoned, and I was prepared to see ghost-like remnants of an old mining town. But, as I looked down into what had been the town, no tumbled-down, deserted buildings greeted my eyes. Instead, as I gazed down, I saw nothing at all. The town of Stone Cliff was gone . . . a wilderness now . . . reclaimed by nature. Only hazy silhouettes of a few old ruins could be glimpsed among the tangled vegetation (and then, only if one knew exactly where to look).

Stone Cliff, the town of my youth, had essentially vanished, and the sights I had stored in my memory had been blotted out . . . erased by time and nature. With a deep sense of regret and loss, I realized I was too late to revisit the scenes of my childhood.

Gradually, though, as I continued looking down upon the wilderness that had once been a busy little mining town, I became aware of a sound. It was the sound of the New River below me. And, as that sound penetrated my thoughts, it became familiar . . . and I realized, while familiar sights may have disappeared from my view, the sound of the river had remained. Unchanged, it was the same today as it had been fifty years ago.

I listened to the sound of the river, and let it carry me back . . . back over those fifty years. Memory after memory returned, and, as I stared at the scene below, it began to change. Excitedly, I began to pick out where the coal haulage incline must have worked its way down from the mountain top to the tipple below, where the company store must have stood . . . and the signal tower, and the schoolhouse, and the black church and the white church, the boarding house, the depot and the power station. And, yes, where our house had been.

And so, with the familiar and unchanging sound of the New River filling my ears, I was able to bring the little town of Stone Cliff, West Virginia, back to life.

Stone Cliff During the Depression: The Year is 1930

Stone Cliff was a typical coal mining community in 1930. Life centered around earning a living in the mines and going to church on Sundays. Its citizens worked for the company, lived in company houses and shopped at the company store. Gardens were carefully tended to supply food necessities and household chores were endless.

Wages ran close to $100 a month (if you worked full-time), and the company took about $12.50 off-the-top for company housing, company doctoring, company coal for heating and cooking, the company blacksmith's services, the company hospital fund and the company burial fund.

My father was a coal miner. He followed his work and we moved with him to each new location — in 1930, the new location was the town of Stone Cliff.

There were no frills, no electricity in the homes, no running water, no indoor plumbing. Drinking water was carried from the spring, household water was carried from the river. Outhouses sat over shallow unlimed pits, had no screens, were not whitewashed and provided fertile breeding grounds for many diseases.

While life was harsh, it was endurable. No one knew, in 1930, that life would soon become almost unendurable for many . . . because no one knew that America was sinking into what would later be called "the Great Depression."

###########################

My life, though, was just fine. I was too young to be concerned with economics or to worry about hard times. I was but a happy, curious boy of five as my family traveled by railroad motor car from Rainelle, West Virginia, to Meadow Creek on New River and transferred to the local passenger train for the last leg of our journey to our new home in Stone Cliff.

And, as that curious boy of five, I immediately set off to investigate. My first day in Stone Cliff, I discovered by looking up you could see snow on the tops of the mountains and by wandering down to the river you could find flowers blooming on its banks. You see, spring came earlier at the bottom of the gorge. And I threw a rock, the first of many, into the New River . . . and wondered where the river came from and where it went. And I listened to the New River . . . and the sound of the river, new to me that first day, soon became a part of my life.

Other sounds became a part of my life too . . . the sounds of the trains that vibrated our house day and night.

Our house was a company house. It sat in the middle of a row of other company houses between the C&O mainline tracks and the river. There was only about 60 feet between our house and those tracks . . . and our house shook from top to bottom almost all day as the trains carried their heavy burdens of coal out of the railroad yard.

You see, the coal company hauled coal up out of the mines in cars that carried about a ton-and-a-half of coal each. An electric motor, driven by power from the power station, lifted the coal up out of the mines . . . then each car was weighed and dumped, and the coal was transferred to a big steel monitor that would haul about five tons of coal down what was called the coal haulage incline. The monitor came down the incline on a railroad track under the control of a cable. (It was a counterweight system, with a loaded monitor going down pulling an empty monitor back up. Miners rode these empty monitors to work.) Once the coal was down the mountain and at the tipple, it was processed and loaded into railroad cars for shipment.

This process went on all day and filled railroad car after railroad car. Those cars would strain against their heavy loads, gather up speed and rumble off down the tracks . . . keeping pace with production . . . and vibrating every house and building in town.

It was a way of life, a routine, repeated in coal town after coal town in the early 1930's. And, as long as the railroad cars full of coal were moving, families were assured of work . . . and wages.

No relief from the vibrations of the trains at night either . . . because passenger trains continued to run throughout the nighttime hours. They'd roar through Stone Cliff, waking everyone in town . . . and, when you woke up, you'd know three things . . . the time (they were always on time), the name of the train (they all had names or numbers) and how long you'd be able to sleep before the next one came through.

Two of these nighttime trains were very special to me . . . the #2 (going through about midnight, headed east to Washington) and the #1 (passing our house about 3 in the morning, headed west to Cincinnati). They were special because if you waited and watched until the last car passed you would get to see a big illuminated picture glowing back at you through the night as the train disappeared. On the back of the #2, George Washington looked back at you, and on the #1, his wife, Martha Washington, did the same.

Day and night the trains moved. Their sounds were inescapable, and those sounds which might annoy a person, or rattle a dish off a shelf, or wake one from a sound sleep, were tolerated, gotten used to, and, after a while, ignored . . . as the routine of life went on.

And the sounds of the trains blended with the sound of the New River and became part of my life too.

Another powerful sound in Stone Cliff, fifty years ago, was the sound of the power station whistle.

Oh, it was loud! And it sounded three times a day . . . at 6 o'clock in the morning to signal power was ready to go for the mines, at noon, and again at 5:30 in the evening to let the miners know power would be shutting down in 30 minutes.

If the power station whistle blew at any other time, it meant an accident had occurred at the mines. Then the power station would blow a series of whistles . . . and all the women and dogs would run to the tipple to await the answer to the question on everyone's lips . . . "Who was hurt?" . . . or . . . "Who had died?"

That series of whistles also alerted the Thurmond railroad yard (the east end of which ran into the west end of Stone Cliff) . . . and a yard engine was dispatched, with a caboose, to take the injured to the McKendree Hospital (located about 10 miles east of Stone Cliff) . . . or worse, to take the dead to the Thurmond morgue.

One of my brothers was seriously injured in one of those mine accidents and wears a silver plate as part of his skull to this very day.

Our house was directly across the tracks from the power station, and the power station's whistle became another sound that was very much part of my life . . . along with the sound of the river and the sounds of the trains.

###################

While not a very large town (the population ran between 200-300), Stone Cliff had its share of very interesting . . . and functional . . . buildings.

First, there was the power station (with its whistle). Inside the power station were huge coal-fired boilers which turned water to steam . . . and the steam turned generators which produced electricity (but only for use by the mines) .

Then, of course, there was our house, a company house, sitting directly across the tracks from that power station.

Now there was a distinct advantage to living in such close proximity to the power station. You see, one way to get hot water for washing clothes and bathing was to carry water from the river and heat it on the stove. But, you could also go to the power station and run hot water off those big boilers! And that's what we'd do . . . one of our daily chores was to scamper across the tracks and bring hot water home . . . just in time to have the big galvanized tub full and ready for our father to bathe in when he came home in the evenings from the mines.

The company houses were, structurally, all the same. They had four rooms, two up and two down . . . with a lean-to across the back. In our house, the two upstairs rooms were bedrooms . . . one for boys (there were four) and one for girls (there were three). The downstairs rooms were my mom and dad's bedroom and a general purpose room. The kitchen and laundry room were in the lean-to area. We ate in the kitchen and bathed in the laundry room. There was a two-story chimney in the center of each house . . . with four fireplaces (one opening into each of the four rooms). The houses were heated with coal bought from the company store.

And then, there was the most outstanding building in town! . . . the company store.

What a place! It was the grocery store, a dry goods store, a hardware store. It was also the post office and the doctor's office. And a railway express agency and a ticket office for the local passenger train. And, it was run by one man . . . the company store manager.

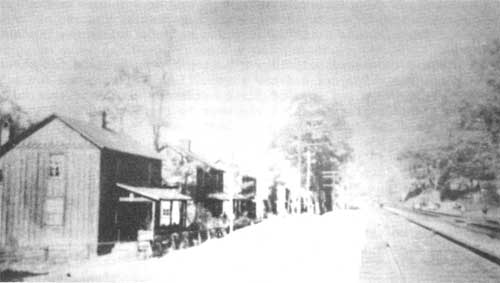

STONE CLIFF, WEST VIRGINIA: 1933

AS VIEWED FROM STONE CLIFF BRIDGE

Left of Railway — corner of company store, depot and

homes. Right of Railway — tipple, power station and school

AS VIEWED FROM THE DEPOT — CLOSEUP OF THE COMPANY HOUSES

Rent was $6.00 per month and coal was $1.00 per month

He stocked the shelves, ordered supplies, dispensed mail . . . and dozens of other things that kept the town's daily business affairs on an even keel. If he ever got into a real pinch for an extra hand, there was only the bookkeeper to help out (the company had a small office in the store, where the company's other employee, usually a local girl, kept the company hooks).

Then there was the one-room schoolhouse. Multiple uses here too . . . eight grades of school for the town's white children (the negro children walked a mile to the black school in Claremont), church for the town's white folks and the civic center for town meetings.

On the east end of town stood the negro church. A two-story building, its top floor was used for special events. Two I recall, with great delight, were when the district's negro singers would come to town and we'd all attend their performance . . . and the other was the annual minstrel show of Silas Green From New Orleans . . . a show that traveled by special railroad car and arrived each spring in Stone Cliff to bring its music and magic to the townspeople.

The boarding house provided room and board to railroad people and to miners who worked in Stone Cliff during the week and returned home on weekends. The company would withhold room and board from these miners' wages and give it to the lady who ran the boarding house . . . who would, in turn, spend the money on food at the company store.

The depot was just a shelter for people to wait in for the passenger trains . . . just a few seats under a little roof.

On the west end of town was the railroad's signaling tower and switching station . . . known by the interesting initials of "CS". You see, in railroad lingo, the place where trains were signaled and switched was referred to as a "cabin". These "cabins" were responsible for supplying power to signal lights, switching devices and the railroad's telegraph system. These "cabins" were known, telegraphically, by their initials (rather than by numbers or by full-length names). Hence, Stone Cliff's cabin was referred to as the CS Cabin.

CS Cabin was a two-story building. The top floor was used for observing activities in the railroad yard and the bottom floor was reserved for a battery room. In this room, rows and rows of glass batteries were kept charged . . . a full-time job. These batteries supplied power to run the signals, some of the motors that switched the trains and the telegraph.

CS Cabin was manned twenty-four hours a day, its employees worked for the railroad and usually lived at the boarding house.

And so, as a boy of five, I led quite an exciting life. As the next few years passed, I became part of Stone Cliff . . . listening for the power station whistle, partaking in the adventures of shopping and doctoring at the company store, attending school in the one-room schoolhouse, going to church, eagerly awaiting the special shows at the negro church, visiting the mysterious switch gear and battery room at CS Cabin, peering out my window at night to catch a glimpse of George and Martha Washington as the crack trains, #1 and #2, passed through at night . . . and wandering along the banks of the New River.

#####################

As I grew older, I began to do more with the river than just explore it, look at it and listen to its sound . . . I began to be involved in how the river was used.

Of course, the river supplied all our household water . . . and I carried many a heavy pail of water from its banks to our house.

And the river made all the difference in our "river" garden. Each family in town had two gardens, a river garden and a mountain garden . . . and everyone helped in the gardens because those gardens were important sources of food. (I know now just how important they were to each family's survival in those depression years.) The gardens supplemented store-bought food stuffs, supplied families with fresh food, contributed mightily to our nutritional intake, provided us with food to can or preserve for winter use . . . and enabled families to stretch precious dollars . . . dollars that were becoming harder and harder to come by as the depression deepened.

The river helped by depositing valuable topsoil along its banks as the spring floods receded each year . . . topsoil that may have washed all the way from the mountain tops of North Carolina and Virginia found its way to our river gardens. (Dams had yet to be built along the New River, so a significant amount of mud, silt and debris was left behind each spring as the flood waters went down.)

These river gardens yielded beautiful crops . . . due to a combination of hard work and their annual renewal of "fertilizer" supplied by the New River.

Another memorable use of the river also occurred when the spring floods were over . . . and the waters of the New River became clear and warm again. It was the spring baptism! And, at Stone Cliff, on a sunny Sunday afternoon each spring, as many as 200-300 people would gather on the south side of the river . . . at what was called "the old sand bar" . . . singing and baptizing. Yes, the whole town participated in this event . . . and the old hymn "Shall We Gather at the River" had special significance . . . because we did gather at the river.

Bright Spots During the Depression: Bridge Talks

People all over the world like to get together and share stories, swap tall tales and exchange tidbits of gossip. It matters little that these stories, tales and tidbits become exaggerated in the telling . . . this only makes them more interesting as they pass along from one person to another.

And the people in Stone Cliff were no different . . . they, too, enjoyed pausing in their daily routine . . . to talk, to listen, to share, to mull over the latest bit of news.

And where did the people of Stone Cliff go to nail down a rumor? to check out the details of the latest story? to share the news? . . . why, to the Stone Cliff bridge. The bridge seemed the likely place to gather dependable information, as many of Stone Cliff's citizens crossed the bridge daily in the course of their routine affairs. (The bridge had been built in 1928 to replace a ferry boat crossing.)

And so, it was on the bridge that the people of Stone Cliff polished the fine art of what my mother labeled "bridge talk". And some of this bridge talk survives to this very day.

Three of the more famous bridge talks are recorded here:

**********************

The "Big Fish Deal" began shortly after the lady who ran the town boarding house dropped by the company store about closing time on a Saturday afternoon.

It seemed the company store manager had overbought fish that week and still had one left in the bottom of the big fish barrel. No one had wanted it, it was too big (it was a 20 pound trout). You see, in those days before refrigeration, food had to be eaten fast (before it spoiled) and there was a limit to how much fish one could eat that fast!

But, as the store manager gave her a very, very bargain-basement price, she bought the big fish and took it back to the boarding house.

Then she started out on Monday morning with fish for breakfast. And, when she packed her boarders' dinner pails . . . in went fish sandwiches. For supper, she cooked up a delicious fish chowder.

Now, for a day or two, this would have gone relatively unnoticed. But, the fish for breakfast, fish for lunch and fish for supper menus continued through Thursday . . . with no letup in sight!

On Friday morning, as the story goes, one of her boarders came down the stairs with a suitcase in his hand. She, looking very disappointed, said "You're not going to leave me are you?" "No Mam," he said, with an absurd twinkle in his eye, "I'm just having this terrible urge to go upstream and spawn!"

The telling and embellishing of this "true story" was bridge talk for many years.

************************

The bridge talk about "Stanley and His Bicycle" concerned a young man named Stanley who worked for the railroad company at CS Cabin.

Now Stanley's claim to fame in Stone Cliff was the fact that he owned the only bicycle in town! (To keep the record straight, Stanley was also a bachelor and resided at the self-same boarding house described in the "Big Fish Deal" bridge talk above.)

It seemed that Stanley had fallen in love with a local girl, and, in due time, a wedding was held. During the ceremony, when the preacher asked Stanley to repeat after him the words "My earthly treasures to thee I endow . . .", one of the prominent local gossips, punched another of her kind, and was heard to exclaim in a loud voice . . . "Well, there goes poor ole Stanley's bicycle!"

This was the stuff bridge talks were made of . . . and another "true story" was added to the Stone Cliff bridge talk repertoire.

*******************

The annual spring baptism led to many a bridge talk. The one recounted here could be titled "When the Very Large Lady Was Baptized".

It was a sunny day, the annual spring baptism was in full swing, several hundred people were standing along the banks of the New River and a young, very large lady (weighing in at about 250 pounds) stepped forward.

Well, the preacher, who was a rather small person in stature, bravely attempted to carry on . . . but he could not get both ends of the lady under the water at the same time. You see, as he would push one end under the water, her other end would bob up out of the water. Finally, an elder stepped out into the river to help the preacher, and, together, they were able to submerge her completely.

Now, if this event had ended right there, it would have turned into an oft-repeated bridge talk in itself . . . but the story didn't end there . . . it continued . . .

It seems as the lady was brought up out of the water, she was shouting with glory and calling out "I saw my Jesus! I saw my Jesus!"

Needless to say, the crowd lining the riverbank was stunned by this revelation (baptisms being taken very seriously). There was a profound silence as they pondered her words. Then, all at once, the town drunk, who was standing right by the river's edge, shouted out in a loud voice "You're a liar! I saw it myself! It was a big mud turtle!"

That local drunk was quickly handcuffed and hauled away by the town constable . . . and, as the car passed over the Stone Cliff bridge, he could be seen through the window . . . grinning from ear-to-ear.

And so another local legend was born . . . and was passed along as "just the plain truth" during pauses on the Stone Cliff bridge.

************

Bridge talks, then, were an interlude in the daily life of the people of Stone Cliff. And bridge talks became just as much a part of that life as the sounds of the trains, the power station whistle and the river.

The best bridge talks were repeated over-and-over, and became bright spots in an otherwise dreary existence . . . as the depression's grip tightened.

The Depression Worsens: The Year is 1932

Back in September 1931, my father's pay, for two-week's work in the coal mines, had been $44.16. For that amount of pay, he had loaded 68 tons of coal and moved 13 cubic yards of slate.

But the problem was, in 1932, that the men were not working year-round. As the depression worsened, and industry-after-industry folded, orders for coal diminished proportionately. Soon, coal was only mined during the winter months . . . to heat homes in the north (around the Great Lakes and in the New England States). Once spring came up north, orders were discontinued and the men were out of work (from May through September).

Of course, the company had credit to extend, to help the miners through the spring, summer and fall months . . . but the credit could only be applied to purchases at the company store. This credit was scrupulously added up, and, when the men returned to work, was deducted from their pay.

With that in mind, let's look at my dad's $44.16 (two week's wages). First, the company deducted $3.00 for rent . . . for the company house we lived in. Then, $1.00 came out for coal . . . for heating and cooking in our homes. There was 50¢ for the company doctor and another 50¢ for the company hospital fund. Take out another $1.00 for the company burial fund and 25¢ for the company blacksmith . . . who sharpened and repaired the miners' tools. This left a total of $37.91 . . . against which my father drew $28.00 worth of script . . . to purchase groceries at the company store. And, the remaining $9.91 was applied to reduce his debts to the company . . . run up during the summer when the mines were not working. So, out of the $44.16 . . . my father brought no money home.

In times such as these, and under conditions such as these, the miners were left with nothing . . . they did not own their own homes, they owed all they could possibly make to the company store and they could not pick up and leave because there was no work anywhere else.

The river garden and the mountain gardens became increasingly important. As money grew almost nonexistent and debts rose to the company store, those gardens became one of the coal miners' most valuable assets . . . and those gardens literally kept starvation from the doors of many a miner's home.

##########################

The people of Stone Cliff, like the rest of the country, did without a great deal during this period of our Nation's history . . . and it was a real and bitter daily struggle to keep hope alive.

During this time, we shared an experience that no one in Stone Cliff would ever forget . . . the town met the World War I veterans who journeyed to Washington in 1932 to petition Congress for their "bonus money".

It seemed that, back in 1920, Congress had voted what it called "bonuses" to all World War I veterans . . . but Congress had also voted not to begin paying those bonuses until the year 1945 (twenty-five years later).

Well, with the depression wiping them out, in 1932, and nowhere else to turn, the World War I veterans wanted their bonus money . . . now.

It was never really an organized march on Washington . . . just one that gathered momentum as the World War I veterans and their families piled onto trains and into boxcars . . . all across America . . . headed for Washington.

As I recall, thousands of these veterans and their wives and children passed through Stone Cliff . . . and the people of Stone Cliff tried to help them. (The veterans were forced to subsist mostly on handouts from well-wishers.) The trains would stop for the night and the railroad detectives would let the people out to sleep along the river banks. With little of their own, the people of Stone Cliff took food and clothing to the veterans . . . offering what comfort they could, and wished them well.

Eventually, the same veterans returned . . . on their homeward journeys . . . empty-handed. They told stories of what had happened in Washington . . . how they had set up a temporary campground and organized a march to petition Congress for their bonus money . . . and how the House of Representatives had passed a bill for immediate payment . . . but how when the Senate failed to act on the measure before Congress adjourned, the War Department, under General Douglas MacArthur (going against the wishes of President Hoover), had burned their camp, crushed their movement . . . and literally driven them out of the city.

The people of Stone Cliff once again listened, shaking their heads, passing out what food and clothing they could spare and offering, once again, what little comfort they could

#####################

Stone Cliff Participates in the New Deal: The Year is 1933

Then, almost overnight, the depression ground to a halt. On March 4, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt became President of the United States and launched America into his recovery plan for the country . . . the New Deal.

Economic reforms were initiated on all levels of life . . . and acronyms like CCC, WPA, NRA and REA became household words.

And, in Stone Cliff, we too were caught up in the country's economic recovery. Yes, Stone Cliff participated! and the town changed!

First, a big new sign went up in the company store window. It was an NRA (National Recovery Act) poster. It had the great big red letters "NRA" printed on the top . . . and a big blue eagle spread its wings under the letters . . . and, under the eagle, the NRA pledge WE DO OUR PART was inscribed.

Now it should be noted that all companies were advised (during the first 100 days of the new administration) to sign the NRA pledge, as this would indicate to the government that the OUR companies were willing to comply with the new NRA policies. For instance, they would pay their workers a minimum wage, require only a maximum number of hours of work and allow workers to form unions.

To encourage the immediate signing of the NRA pledge, companies were also advised that if they did not sign the pledge, no one would be allowed to buy their products.

And so, the WE DO OUR PART pledge was duly signed by the coal company in Stone Cliff . . . and the NRA poster, acclaiming that fact, went up in the company store window.

######################

Under one of the New Deal programs, families received groceries . . . called "commodities". These commodities, however, were not free . . . a minimum number of hours had to be worked before a family was eligible to pick up their allotted commodities (usually flour, butter, rice, potatoes, cheese, etc.)

I remember one particular day when each family received a new kind of commodity . . . a big bag of grapefruit! Having never seen grapefruit before, there was a great deal of speculation as to how to cook them.

I overheard a lady ask my mother, "How in the world do you prepare these grapefruits? My, they're so bitter! I have tried to boil them, I have tried to brown them, I have tried everything I can think of and they still taste so bitter!"

|

STONE CLIFF, WEST VIRGINIA: 1933 |

|

C&O RAILWAY'S Signal and Switching Tower (east end of Thurmond yard)  L: Bonnie Shuff Whitener, age 2, both in Stone Cliff R: Sister Freda Shuff Menefee, age 15 |

VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE Company store, depot, coal haulage incline and tipple

|

So, my mother took up the challenge of "cooking" grapefruit . . . and, at the same time, removing the bitter taste. She won too, and to this day I use her recipe . . . cut them in half, remove the seeds, add brown sugar or honey and place them in the oven allowing the sugar to melt into the grapefruit.

####################

Thinking back about how miners were required to work a minimum number of hours to be eligible to receive commodities, reminds me of another interesting change that occurred during the early New Deal days in Stone Cliff . . .

Now, if a miner worked his minimum number of hours in the mines, he received his wages . . . and no commodities. But, if a miner did not work the minimum number of hours in the mines, he could complete his hours by working on an approved government project . . . and then receive commodities.

Well, in Stone Cliff, the government's project, which kept miners working the required number of hours, was to build outhouses . . . yes, outhouses.

But these were not just ordinary outhouses . . . oh, no! These outhouses were built to government specifications! and were sanitary! They had concrete floors over deep pits, the pits were limed to kill germs, the houses were white washed . . . inside and out! Bug screens covered the windows!

Yes, these outhouses were a wonder to behold. They were pleasant to use too. An added benefit was that these santiary outhouses played a key role in the decline of the spread of sanitation-related diseases all across the United States.

###############

Another part of the WE DO OUR PART pledge had assured the miners the right to unionize (with government protection). A local was formed in Stone Cliff, my father was a member, the new union rented out the top floor of the negro church for a meeting hall . . . and one of the first agreements they negotiated with the coal company was that, if a miner was injured, the company would provide ambulance service from the mines to the hospital. Thus doing away with whistling for a yard engine and caboose from the Thurmond railroad yard when an accident occurred.

#################

The school changed too. The New Deal also had a program which supplied fresh milk to school children . . . every day . . . if the school met New Deal standards.

So, our one-room schoolhouse was closed, and we walked part-way and took a bus part-way to the Claremont school . . . where we had two rooms and the classes were separated (four grades to a room instead of eight). And each day, about noon, a train would stop and set off a pint of fresh milk for each school child.

As progress continued to roll on, we changed schools again. This time we went to a four-room school in Thurmond. We'd ride a bus from Stone Cliff to the bridge, walk across the bridge and then on to school.

##################

In the fall of 1936, we were let out of school one day for a very special treat . . . the Presidential race was in full swing and Alfred Landon was running against Roosevelt. Landon, and his running mate Knox, were traveling across America, on a railroad train they called "the campaign train" . . . giving speechs and trying their best to persuade Americans to vote Republican.

That day, we school children were part of one of Alf Landon's whistlestops. Oh, it was glorious! . . . Landon made a speech from the rear platform of the train, people cheered, flags waved . . . and buttons, shaped like sunflowers, were thrown to the crowd by Landon's aides.

Of course the local Democrats, not to be outdone, had plenty of FDR buttons to distribute too! (I still have those two buttons as keepsakes of my very first encounter with a Presidential candidate.)

#####################

Before the New Deal, only the mines had been supplied with electric power (from the power station). But, with the New Deal came electricity for the rest of the town and we now had electric lights in our homes . . . and coal oil lamps disappeared (along with the daily chores of cleaning and filling them). Eventually, the power station closed altogether and was replaced by the Appalachian Power Company.

We bought our first radio . . . from Montgomery Wards . . . and life in the evenings changed even more as we sat by the fireplace listening to Lowell Thomas, Kate Smith, Amos and Andy . . . and on Saturday nights, the Grand Old Opry from Nashville, Tennessee, brought to us by radio station WSM. While we listened to these programs, we played checkers, or read . . . and had snacks.

With electricity . . . came telephones . . . and life changed even more.

####################

In town after town, all across America, people were pulling themselves out of the great depression and entering the era of the New Deal. And the little town of Stone Cliff, a small coal mining community on the banks of the New River in West Virginia mirrored this progress and change . . . many old ways were set aside forever . . . new ways were taken up . . . and people looked ahead, again, to the future.

And those World War I veterans who had been treated so harshly just a few years earlier . . . well, their story, too, had a new ending. Under FDR's administration, they were treated kindly, listened to . . . and received their bonuses earlier after all.

######################

In 1938, when my dad took a job with another coal company, we moved away from Stone Cliff. I remember saying goodbye to the town when we left . . . it was a sad day for me . . . so many memories packed into those eight years. I had been five years old when we came to Stone Cliff . . . I was thirteen when we departed. I would miss it.

Stone Cliff Today: The Year is 1983

Now, in 1983, fifty years later, I had returned to Stone Cliff. Closer inspection along the mainline tracks revealed a few old crumbling gravestones . . . Stone Cliff had had two cemetaries, one for white folks and one for black folks, one on each side of the tracks. These graves and a few old masonary foundation corners of long-gone buildings were all the physical evidence I could find to tell of the people who had lived and died at Stone Cliff.

And, as I stood again on the bridge, looking down at what was once the busy little mining town of Stone Cliff, West Virginia, I thought how history repeats itself along the banks of the New River . . . you see, Indians lived along the New River, they are gone, the river remains. So, too, did the French fur trappers live along the New River, they are gone and the river remains. The same is true of the early English settlers. Then America's early mining industry took up residence along the New River . . . and built a town and mined coal. That town is gone and the river is, once again, the only surviving landmark.

Yes, the whistle of the power station is silenced forever, the buildings have decayed and vanished, the people have died or moved away . . . but the river and its sound remain . . . unchanged.

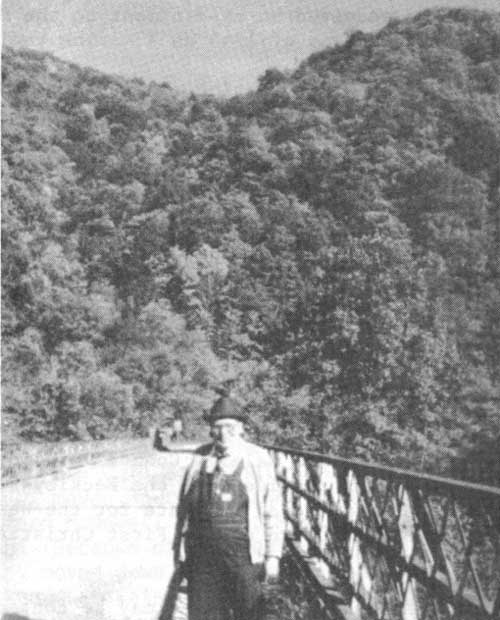

The Stone Cliff Bridge and vicinity after nature has reclaimed the area of the coal haulage include and tipple — Murray Shuff returns to the town of his youth after fifty years and finds only memories.

Stone Cliff

West Virginia

1983

|

Showing the wilderness scene that was once the

location of the town of Stone Cliff — Clara Shuff Ashley

relaxes at the scene of the "bridge talks." |

About the Author:

Murray Shuff was born in the town of Thayer, on New River, in 1925. He attended school at Stone Cliff, Claremont and Thurmond. After serving in the Navy during World War II, he received an appointment to the Merchant Marine Academy and graduated with the class of 1945 as a marine engineer.

Signing on with the Gulf Oil Corporation, in research and development and foreign service, his worked carried him to many countries, including Venezuela, Columbia, Iran, Iraq, Oman, Arabia, Egypt, Brazil and Argentina. He was called back to Naval service during the Korean conflict and served with the Atomic Energy Commission.

In 1959, he returned to West Virginia, to Beckley, and was employed by the Meadows Lumber Company — he now serves as president of that corporation.

Some of his civic activities have included being past area governor of Toastmasters International (where he received the highest honor of distinguished toastmaster) and serving as youth leadership training advisor for 4H Clubs for twenty years and advisor and director of Future Farmers of America for Raleigh County for twenty years. Mr. Shuff also helped organize the first Raleigh County Historical Society Chapter and has served as its president, and has been an advisor, for fifteen years, to the Raleigh County Vocational Education Board. In addition, he is a past president of the Beckley—Raleigh County Chamber of Commerce, has been a national delegate for the West Virginia Lumber Association and a chairman of the board of the First Christian Church of Beckley.

Mr. Shuff currently resides in Beckley and may be contacted at P.O. Box 1638, Beckley, West Virginia, 25802.

Acknowledgements:

Grateful acknowledgements are extended to:

Mamie Thompson (long-time bookkeeper at Stone Cliff and various other coal companies) and Clara Shuff Ashley (sister of the author and long-time resident of Stone Cliff) — for the use of their historical photographs which make the story of Stone Cliff seem so much more real.

Walter Ignatovich and the Central Printing Company in Beckley — for their valuable technical assistance with the photography and printing of this article.

Irene Engelhaupt of Beaver — for her assistance in compiling and editing the manuscript.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

newriver-84/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 08-Jul-2009