|

Stories in Stone

|

|

CHAPTER X

A NEW METHOD OF OBSERVATION

AN interesting account might be written of the methods of obtaining geologic and geographic information. The geologist goes into every available nook and cranny of the earth, with eyes open and mind alert, to note each object of interest and to mentally grasp every significant relationship. He explores hill and plain, river and lake, bay and ocean. He descends into mines and caves; he traverses canyons and climbs mountains. Where he cannot go, he sends self-recording instruments. By bucket and cable he sends these instruments to the bottom of deep wells, and by balloons he sends them high in the air to altitudes greater than those of the highest mountain peaks.

The manner of his going is as varied as his methods of travel, for he uses every available means of transportation. He travels on foot and on horseback, by steamship and canoe, by camel, caravan, and dog team, and even by airplane.

Many a book has been filled from cover to cover with tales of travel, and many another has been devoted to descriptions of the methods and results of scientific observation. It is useless to attempt even the most condensed account of methods of geologic exploration in the space here at my disposal, and for this reason I shall confine my attention to the newest method of travel—that by means of aircraft.

Near the close of the World War I was engaged in geologic and geographic work along the Atlantic coast. Much of the area that I wished to examine is marsh land. Examination of it on the ground was slow, laborious, and generally unsatisfactory. It seemed to me that some of the information desired as to the character of the surface could be obtained by observation from airplanes and by the use of cameras adapted to taking views of the land from high in the air.

In order to test this method of observation I spent about a year making flights in airplanes and in hydroplanes, collecting photographs taken from the air, and studying the character of the surface, both by observation from the air and by the inspection of these photographs. This work was made possible by a cooperative arrangement between the United States Geological Survey and the Army and Navy air services. The Army Air Service placed airplanes at my disposal at Boiling Field in Washington, D. C., at Langley Field in eastern Virginia, and at Mineola on Long Island. The Navy Air Service gave me similar privileges at Washington and at Rockaway, Long Island.

What is it like to mount high in the air and look down on the surface of the earth as one bends over a map spread out on a table? We hear conflicting stories of the sensations experienced by those who have taken trips in airplanes. Let me digress for a moment and tell you of one of my first flights, made from the aviation field at Mineola.

An Experience in the Air

The morning selected for the ascent was fair, but clouds that hung low on the horizon looked threatening. I had spent the night at the Officers' Club in order to lose no time in reaching the field in the morning, for we were to hop off as soon as the light was strong enough to permit us to take photographs.

We scanned the weather chart, noted the velocity and direction of the wind, and reached the decision that the storm promised by the weather man need not delay our trip in the air. But we lost some time in getting into flying togs and in warming up the motor.

|

|

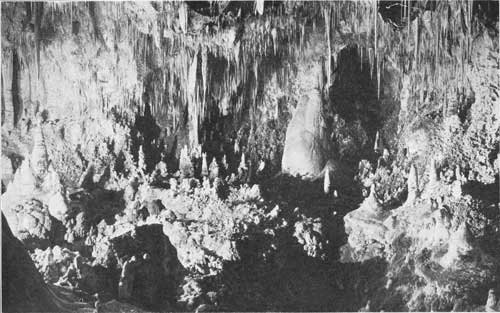

PLATE XL. HEART OF

THE BIG ROOM, CARLSBAD CAVERN, NEW MEXICO.

An illustration of the intensive decoration of the cavern. Floor, ceiling, and walls are completely covered with cave marble in infinite variety and form. For size, note the people standing in the center of the scene. Photograph by Willis T. Lee. Courtesy of the National Geographic Society. |

|

|

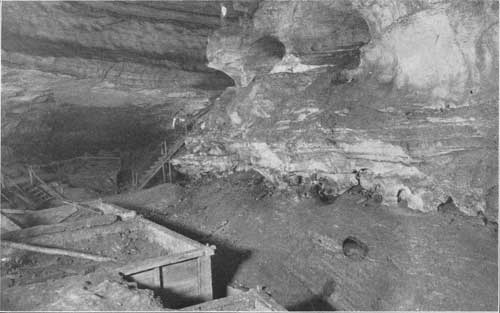

PLATE XLI. A CHAMBER

IN MAMMOTH CAVE.

Limestone walls and saltpeter vats in Booth's Theater. The nitrate-bearing earth, which had accumulated through long ages on the floor of the cave, was here leached out for the manufacture of gunpowder in 1812. Photograph by Willis T. Lee. |

The biplane that carried me on this, my first, air journey was called Sky Pilot. I smiled at the name painted in large letters on the body of the plane, but on second thought that name did not seem wholly humorous. I was willing to be piloted away from earth for a little time but not permanently. I think I should have felt more comfortable had the biplane carried a less suggestive name.

I looked the machine over with critical eye. It had an awkward appearance. Like an eagle, which appears awkward and unattractive while on the ground, a biplane in repose can scarcely be called a thing of beauty. But when, like the eagle, it leaves the ground and rises easily and gracefully into the air it becomes an object of fascinating interest.

As we take off, we give little attention to appearances. Who cares for looks when deeds are all important! Onlookers may admire if they so desire; or they may smile at us if they please. Just now things of much greater import demand attention.

During the delay the clouds have approached, and even as we leave the ground the vapory forerunners of the storm are scudding past. We carefully adjust our goggles, for no unprotected eye can endure the blast of an airplane propeller, and take off, heading into the wind. For several moments we rise on a straight course in order to gain altitude. This course brings us close to a bank of heavy clouds. The dark masses look ominous as they threaten to engulf us. But our mechanical bird ignores the threat, wings its unobstructed way between two dark masses of vapor, and rises into a clear, brilliantly sunlit space above the clouds.

How different now!

A moment ago cloudy troubles darkened our sky; the silver linings seemed thin and lacked comfort, but now we gaze down on white, billowy masses that glow brilliantly in the sunlight. From above we can see nothing of the cloud except the silver lining.

As Sky Pilot mounts higher into the clear space the cloud that had threatened us for the moment seems to shrink and lose its impressiveness, and my attention suddenly returns to earth. But where is the flying field we left a few moments ago? I can not distinguish it. And what is that great, even surface that stretches endlessly beyond the reach of vision? I try to ask the pilot, but the roar of the engine is so deafening that no sound produced by human voice can be heard. Instead of words coming from my opened mouth a blast of air from the propeller goes into it and expands my cheeks like those of a puff adder. An airplane is an excellent place in which to learn to keep one's mouth shut. I have certain acquaintances who might take trips in the air frequently, with profit to themselves and others.

But sign language can be used, and, as if in answer to my bewildered look, the pilot makes a sign indicating waves of infinite number. Then I understand that I am gazing out over the Atlantic Ocean. Hastily I look down for dear old terra firma. I like water, but not too much at one time! I am not an expert swimmer!

But my faith in good old Sky Pilot is unshaken. There is no danger of falling into the water. Yet, some time ago—but of course there is no danger now! Oh! no. Nothing can happen today—but some time ago, something did happen and an airplane fell. I reflect that perhaps one might alight in water more easily than on land, for in most places land is hard. I signal to the pilot that the waves are very interesting—oh, very!—but there is no variety of scenery. They look much alike to me, and I have already seen enough of them. Things on land are more varied and in every way more interesting.

But where is the land? I look over one side of the airship and see only waves; then over the other side and see only blue, limitless sky. After a startled moment, I understand that in making the turn, the plane banked or tilted. My pleasure in this matter had not been consulted. But before I have opportunity to complain, good old Sky Pilot gracefully rights itself and recovers its former standing in my estimation, as sky and earth again appear in the relation that I have always assumed was proper for them.

The pilot now points to a white strip of land which stretches uninterruptedly as far as eye can reach. It slowly dawns on me that beach sand is white and that there are considerable quantities of it on the south shore of Long Island. The white strip is the sandy beach, on which the surf is breaking in white foam.

We now fly westward over the beach. Here lies Rockaway beneath us, and there is Coney Island. But these places look like little toy towns, composed of play houses. Toy boats appear out at sea—ocean greyhounds from over the water coming into New York Harbor. Other toy boats are leaving the harbor, destined for the ends of the earth.

To our right are cities and towns, orchards, and cultivated fields. A wormlike object is creeping along a dark trail—the Express headed for New York. Small, dark specks looking like ants on a white pathway must be automobiles on the cement turnpike. But what is that light strip beyond the dark land? Is it possible? Yes, that must be water. It must be Long Island Sound. A minute speck on it from which trails a long black streamer of smoke is a steamboat, and the dark land beyond must be Connecticut.

In answer to a signaled inquiry the pilot points to the altimeter, which registers 8,000 feet. One who flies a mile and a half above the ground can see a long way. Yes, I am really looking across Long Island and over the Sound far away into Connecticut.

On we go—for go we must, if we would stay in the air. No signs forbidding loitering are needed along the airways. The rule is go on or go down. So, on we go!

Brooklyn now lies beneath us. Doubtless there are people on the streets, but we can see none. The minute moving dots we see are busses and street cars.

|

|

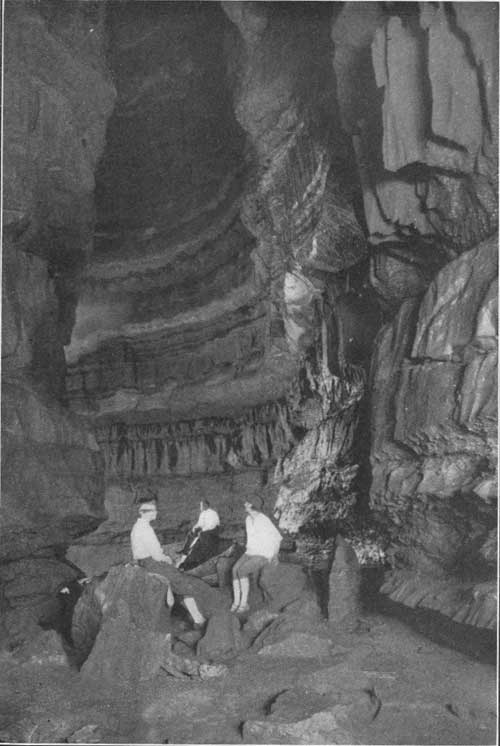

PLATE XLII. A DOME

IN MAMMOTH CAVE.

Cathedral Dome, about 60 feet in diameter and 200 feet high. This dome was formerly approached through Mammoth Cave proper but is now reached through the new opening to the cave. Photographed by Willis T. Lee. |

Objects now flash into view so rapidly that I become bewildered. East River, with its great bridges and with its ferry boats coming and going; the harbor, with great steamers churning up the mud as their powerful propellers force them here and there; the enormous skyscrapers—but hold! are they so enormous? As we look down upon them, one is scarcely distinguishable from another. Height is not gaged from above. A five-story building and a fifty-story building may look much alike.

Suddenly the pilot points to the clouds rolling in from the sea in dense masses and signals that we must return before the storm breaks.

Looking a Thunder Storm in the Face

Then I recall the storm promised by the weather man. As we head eastward toward the rolling mass of clouds my attention is riveted on the difficulties ahead. All the wonders beneath us are forgotten for the moment. In spite of reason, I find it impossible to suppress the feeling that we are about to smash head foremost into a mountainous mass of solid matter, as we approach the thunder cloud.

How one's thoughts race at such a moment! In a flash I have a plan all worked out and supported by unanswerable arguments: rather than plunge into that cloud, where we may collide with thunderbolts, it will be much better to fly over into New Jersey ahead of the storm and land in some lady's flower garden, or perhaps in a soft cabbage patch, even if I have to pay for the ruined cabbages.

However, the pilot shows no concern and does not consult my wishes. But he glances sharply through every rift in the clouds, and his practiced eye picks up familiar objects on the ground.

Suddenly Sky Pilot swerves, circles about for a moment, and dives through a break in the clouds like a bird of prey swooping down upon its victim. Through this rift we pass suddenly from the dazzling brilliance of a perfectly clear sky to the somber shadows beneath the storm clouds and reach the landing field well ahead of the rain.

I have never told the pilot about my plan to visit New Jersey, nor of my willingness to compensate irate owners of ruined cabbages, but I have had the pleasure of assuring him that he gave me an experience that I can never forget. Never before, nor since, have I been so close to a thunder storm in action.

This adventure, novel as it seemed at the time, was by no means my only unusual experience. Adventures in the air are all novel, but as I grew accustomed to the unusual sensations my attention became fixed more completely on the things that I was there to see and on the consideration of methods for presenting the results of the observations.

|

|

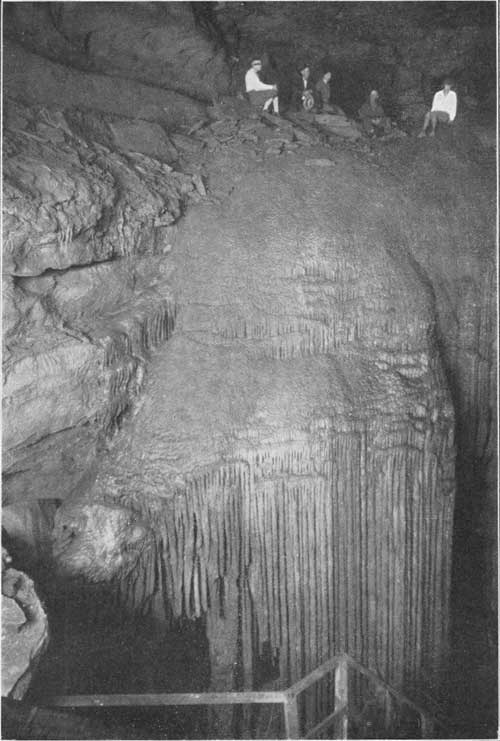

PLATE XLIII. FROZEN

NIAGARA. DECORATIONS OF ONYX MARBLE IN THE NEW ENTRANCE TO MAMMOTH

CAVE.

|

Commercial and Scientific Uses of Airplanes

Many others are interested in the face of the earth as it is seen from the air, and many are devoting time and thought to the adaptation of the airplane to scientific study. I was obliged to abandon this work, but others are continuing it, and much has been done to adapt the airplane and the camera to use as instruments for mapping. Considerable has also been done toward the adaptation of the airplane to use as an instrument for prospecting. It has been used by those who make search over broad stretches of country for prospective oil fields. Planes have been used for this purpose in Canada, Central and South America, and elsewhere.

The value of this commercial use of airplanes depends on the fact that from the air we may obtain a broad view of an area or an object, unobstructed by other objects in the foreground. This fact suggests other uses. The employment of airplanes by sightseers has long been advocated, and in some measure they have been used for viewing landscapes. Thus far their use has been confined chiefly to professional air men. But since these pioneers have blazed the trail, that trail will be followed by multitudes, unless in this instance the ordinary trend of history is reversed. The possibility of viewing landscapes from the air and of studying them from any point of view is illustrated by many of the photographs reproduced in this volume.

As airplanes and the cameras used in them are among the newer instruments to be adapted to the mapping of the surface of the earth and to delineating its features, it seems appropriate to point out here some of the obvious advantages gained by the use of these instruments.

It is a well-known fact, that in viewing an object, the part of the object that is close to the observer seems more prominent than equally large parts at a greater distance. In order that all parts may be seen in proper proportion, the object must be viewed from some distance. The larger the object, the farther away must the observer be in order that its constituent parts may appear in proper proportion.

In viewing places from the ground great difficulty may be experienced in selecting the best point for observation. Much time is spent in the national parks selecting scenic points and building trails to them. By use of an airplane any desired point of view may be occupied easily. Furthermore, when the landscape is viewed from the ground there are often unattractive objects in the line of vision which interfere with the view desired. In an airplane we rise above all petty obstacles and reach a position from which our view is unobstructed.

The ability to choose one's viewpoint is useful in many ways. Geographic information obtained from photographs taken from airplanes has been of great value to the landscape architect whose duty it is to lay out city parks in artistic pattern and to the engineer engaged in city planning. The most detailed map of a given area may fail to show the location of some object which the mapmaker regarded as unworthy of notice but which is of great interest or importance to the user of the map. The camera is no respecter of objects. It depicts every object with equal faithfulness.

The Picture Map

When a picture is desired of an area too large to be photographed on a single film a composite picture is made, which some call a mosaic and others a picture map. A mosaic is made up of photographs taken at regular intervals of time by a camera carried over such an area in an airplane. The pictures are then corrected for distortion, difference in scale, and other imperfections, and fitted together to make a continuous picture map. Great difficulty is experienced in making the corrections, and although the mosaics serve many useful purposes the methods of making them have not yet been perfected to a stage where they may replace other kinds of maps. They have, however, reached a stage where maps made from the pictures supplemented by ground surveys are more accurate than maps made from ground surveys alone.

Mosaics have been made of many of the well-known parts of the country, such, for example, as Boston (including the harbor and surrounding land), New York and neighboring parts of Long Island and New Jersey, Chicago, San Francisco, and many other cities. Unfortunately, the picture maps are so large that they can not now be used as illustrations in books like this one.

Before me as I write is a picture map of an area of about 400 square miles in California, including Los Angeles. The map is about 5 feet square. Its scale is too small now to show distinctly objects much smaller than city blocks. A further reduction in size would obliterate much that is desired on such a map. It is to be hoped that ways may soon be found to publish such mosaics at a reasonable cost. They are too useful to lie in obscurity.

In viewing a landscape from the air one gets an impression of it similar to that obtained from a map of the country. My first impression of this kind is one never to be forgotten. I had been making observations in eastern Virginia for some time and was familiar with the geographic features as they appear from the ground and as they are represented on the map.

Then one day at Langley Field, the flying station north of Norfolk, Va., I stepped into an airplane and was lifted several thousand feet into the air, where I spent three hours looking at the country from this new point of view. The flight took me over Dismal Swamp and westward nearly to Richmond and northward to the Potomac River. Then we turned eastward to the shore of Chesapeake Bay and flew southward over the numerous streams, bays, and marshes of eastern Virginia. During the entire flight I gazed down on familiar scenes with a feeling that I was looking at a map. Every stream, town, and road was clearly visible and plainly recognizable.

Air Journeys Over Difficult Places

Observation from an airplane is particularly useful in areas difficult of access, such as marshes, swamps, and mud flats, and in tracts cut by streams and inlets into an intricate complex of land and water. Many of the marshes and mud flats in eastern Virginia are impassable and can be seen only from above.

Some parts of the West are equally impassable, but for a very different reason. There are badlands cut by deep, narrow arroyos. There are sun-parched deserts like that of Death Valley. There are precipitous walls which have never been scaled, like those of the Grand Canyon. But the flier soars over mud flat and mountain alike and looks down with the same equanimity upon unscalable wall and impenetrable marsh.

A peculiar advantage is gained by use of airplanes in mountainous districts. This advantage is obvious to anyone who has tried to illustrate mountain scenery by photographs or by other means. From such a distance that a large mountain appears in proper proportion all details may be lost. From nearby points we are likely to see only undesirable foreground. By use of an airplane we may select our point of view, look a mountain peak squarely in the face (Plate XXXIII), or gaze down into the very throat of a volcano, such as that shown in Plate III.

Much work has been done in constructing relief maps and plaster models, and in devising other means of representing mountainous areas, for the purpose of showing clearly the interrelations of mountain and plain and of ridges and canyons. Pictorial representations of these things can now be obtained from the objects themselves by means of air photography.

Seeing Things Under Water

An advantage of a still different nature is obtained along the seashore and in areas of shallow water. From a distance above the surface we are able to look down through a considerable body of water and to distinguish objects on the bottom. During the World War submarines were "spotted" and followed by observers in aircraft.

In the course of my airplane work along the Atlantic coast I found that I could see on the bottom not only such objects as sunken boats but submerged land forms like the terraces and sand banks off Pensacola, Fla. (Plate XLVIII), and the channels, both natural and dredged, in rivers like the Potomac (Plate XLIX). Little has been done toward adapting this method of observation to the study of geology and physical geography, but it seems to offer great possibilities of usefulness.

Another way in which the airplane may be found useful to the geologist is in the examination of rock formations and the search for bodies of minerals. I have no thought of suggesting that this method of observation will ever entirely supplant the slow, laborious methods of work on the ground, but there are many ways in which a rapid survey of an area made by flying over it may be useful.

Each kind of rock has recognizable characteristics. Some are red, others gray, and still others brown or black. Certain kinds of plants thrive on limestone and not on sandstone. Some rock formations weather into cliffs, others into broken surfaces, and still others into smooth level surfaces. These characteristics may be seen from high in the air and recognized from air photographs. Geologists of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during the World War were able to identify geologic formations from air photographs and after ascertaining the characteristics of these formations where the rocks could be examined they were able to map the same formations in areas behind the enemy's lines and so to point out favorable routes of march along which firm road beds might be found.

An intensely practical use of geology to fliers came to my attention some time ago. The geologic formations of England have long been studied, and a complete geologic map of the country has been made. Each kind of rock has a special color and habit of weathering. Certain types of trees and shrubs thrive on it which do not thrive on neighboring rocks of other kinds. Aviators who had studied the geology of England with a view to recognizing the surface from aloft found that, with a small geologic map before them, they were able to determine their location.

The official who developed this method of observation said that in flying across the Channel from the continent he often ascended to great altitudes to avoid unfavorable flying conditions, and was frequently above clouds which obscured the ground. On descending through the clouds somewhere over England he could first recognize by the general aspect of the country the geologic formation he was over. By reference to his geologic map he ascertained his approximate position. By the time he had approached the surface near enough to recognize towns and smaller objects he had headed in the general direction of his destination and was able to recognize the smaller objects which served as more exact guides.

Airplanes and Charts

There is probably no way in which an airplane is of greater use to the geologist than in making maps and charts. Since the great development of the airplane during the World War as an instrument for observation, methods of using it for making maps have been developed rapidly. From the many adaptations that might be mentioned, two may be selected as representative—the charting of coast lines and the mapping of such features of an area as fields, forests, towns, roads, and streams.

It is necessary for the safety of ships that coast lines be accurately charted, and that the charts be revised when changes take place in the relation of land and water. In many places the coast line may be notably shifted during a storm. In a large country like the United States, which has more than 52,000 miles of coast, the problem of maintaining up-to-date charts is difficult. Revision of a chart of the shore line where it has been changed can be made readily from airplane photographs.

The airplane has already abundantly proved its worth as an effective instrument for making maps, and new ways are being devised for still further increasing this kind of usefulness. It is quite impossible to describe in the limited space of this brief chapter the methods by which the results of observations from the air are transferred to paper in the making of a map. I must be content with the statement that the several mapmaking organizations have found that the use of the airplane has materially reduced the cost of mapping, hastened the process, and greatly increased the accuracy of the maps. In a recent report, the committee on photographic surveying of the Federal Board of Surveys and Maps states that an average saving of 25 per cent in the cost of its maps is made by the United States Geological Survey through the use of air photography.

The speeding of the output of the mapmakers is timely in view of a recent law that provides for the completion of the map of the United States within twenty years, although Congress has made no appropriation that will expedite the work now being done. In order to accomplish this task great speed would be necessary, for less than half the area of the United States, which includes more than 3,000,000 square miles, has been mapped in the way contemplated by the United States Geological Survey.

I may add that this committee states that in 1924 the Army Air Service supplied to the Geological Survey air photographs covering nearly 900 square miles for the purpose of making standard topographic maps, and that in 1925 photographs of 9,300 square miles were supplied for this purpose. For 1926 photographs have been requested for 36,000 square miles in the United States proper and for 20,000 square miles in Alaska.

|

|

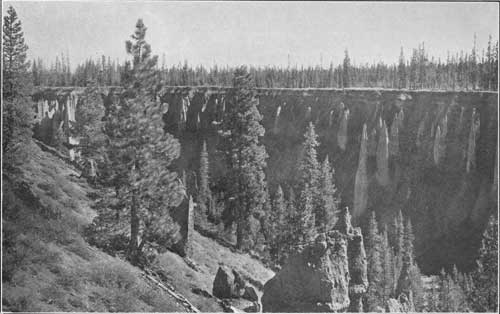

PLATE XLIV. RAIN

EROSION IN SAND CANYON, CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK.

The needle-like pinnacles in the side of the canyon are remnants of recent erosion in the lava beds of an old volcano. Photograph by Fred Kiser. Courtesy National Park Service. |

|

|

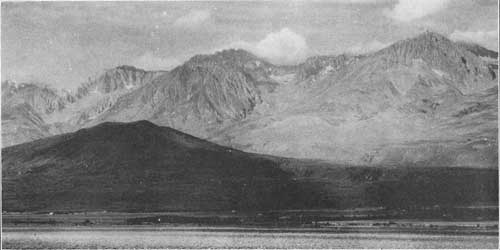

PLATE XLV. VIEW OF

THE EASTERN FACE OF THE HIGH SIERRA, CALIFORNIA, SHOWING A GREAT FAULT

SCARP AND A VOLCANIC CONE AT THE FOOT OF THE SCARP.

The floor of Owens Valley, shown in the foreground, consists of sand and gravel, which supports a sparse growth of desert vegetation, chiefly sagebrush. The buildings and trees in the middle distance mark the course of Owens River, which now supplies water for the City of Los Angeles. The great dark mass at the foot of the high mountains consists of igneous rock. The higher of this mass is the cone of an extinct volcano, built up during a long succession of eruptions of molten lava, which issued from the vent in the center of the cone and spread over its flanks and to some extent over the floor of the valley. Photograph by Willis T. Lee. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

stories_in_stone/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 31-Dec-2009