|

Vanguard of Expansion

Army Engineers in the Trans-Mississippi West, 1819-1879 |

Chapter V

THE SOUTHWESTERN RECONNAISSANCE 1849-1860

A complex mission faced the Topographical Engineers in the territory obtained from Mexico. Numerous expeditions, with assignments tailored to fit the needs of specific locales, went into the Southwest. Some places required basic exploration; others, more settled, needed roads to connect towns and forts. Elsewhere, topogs located sites for military posts and railroad passes, reconnoitered rivers, and improved harbors. From the Grand Canyon to the Great Salt Lake, San Antonio to San Diego, the topogs crossed and recrossed the Southwest, examining the new country and binding it to the old.

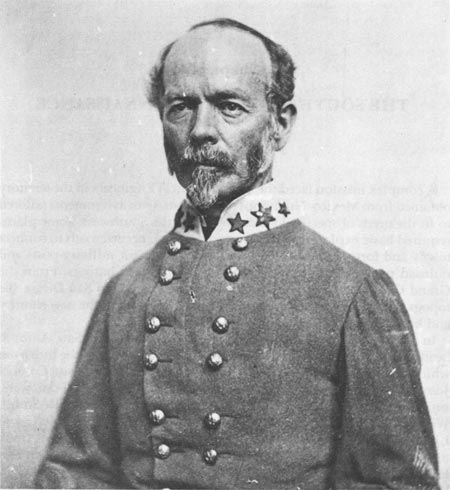

In Texas, where the great need was for roads, the San Antonio headquarters of the Army's Department of Texas served as the hub from which exploring parties sought potential routes. Lieutenant Colonel Joseph E. Johnston, a veteran of the Seminole and Mexican wars, supervised the effort, and four topogs (Lieutenants Martin L. Smith, William F. Smith, Francis T. Bryan, and Nathaniel Michler), and Lieutenant William H. C. Whiting of the Corps of Engineers undertook the reconnaissances. Unlike the complex scientific surveys of Abert and Emory, the work done under Johnston was practical and grindingly hard. With two potential enemies, Mexico across the Rio Grande and numerous bands of hostile Indians on both sides of the river, Texas desperately needed a network of roads between posts along the border and in the interior. From 1849 to 1851, Johnston and his five hard-working assistants overcame many obstacles, from thieving bands of Apaches to the dry tableland between the Concho and Pecos rivers, to lay out a basic system of transportation and communication that tied the forts and towns together. [1]

The last expeditions in Texas before the Civil War, led by topog Lieutenant William H. Echols in 1859 and 1860, were among the most unusual of the entire southwestern reconnaissance. Although his assignment was conventional—examination of western Texas between the Pecos and Fort Davis and survey of a road between Forts Davis and Stockton—his pack animals were not. Echols and his escort carried their supplies and equipment on camelback. On his first assignment after graduation from the Military Academy, Echols was the second officer to conduct an extensive field test of the camels. [2]

|

| Joseph E. Johnston. National Archives. |

In many ways camels were ideally suited for the arid Southwest. They drank only once every three days, and carried 500-pound loads. Their large, flexible lips took in food without aid of the tongue and thus preserved moisture. But they also had drawbacks. Their stench drove horses crazy, and their frightening growl made them unpopular among the soldiers. A man who loaded a smelly dromedary while the animal groaned and spat its foul, sticky cud, did not soon forget the experience. If he angered the camel, he also had to look to his kneecaps, not just at the moment but for some time thereafter. Camels remembered abuse and sometimes waited for days before finding an opportunity to knock down a soldier, lie on him and crush him, or bite off a kneecap or arm. For all their suitability, the camels were distrusted and disliked by men who worked with them. [3]

Echols's 1860 tour of the arid and extremely rugged Big Bend country provided an excellent test for the camels. On the "roughest, most tortuous and most cragged" trail he had ever seen, Echols and his men suffered immensely for lack of water, and the mules became too weak to move. The camels, on the other hand, stood the torture well and proved just as sure footed as the mules. Echols's journal is full of praise for the durability and strength of the new pack animals. After one particularly trying day he said simply, "No such march as this could be made with any security without them." The department commander, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee, agreed that the camels proved themselves in the Big Bend. Lee praised their "endurance, docility, and sagacity," and attributed the success of the reconnaissance to their "reliable services." [4]

The Echols expeditions ended both the survey of Texas and the camel experiment. The War Department's request for one thousand of the animals found little support in a Congress preoccupied with sectional tensions. When the Civil War started, the Army had 111 camels, 80 in Texas and 31 in California. Neither the camels in Texas, which became Confederate prisoners of war, nor the others received proper care. All of them ultimately found their way into the wilderness where they died off. The country was concerned with more important matters. [5]

Like the Texas reconnaissance, the postwar exploration of New Mexico began in 1849. Captain Randolph B. Marcy, escorting an emigrant caravan from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Santa Fe, led the first expedition into the territory along the south side of the Canadian River. Lieutenant James H. Simpson, eleven years a topog, rode with Marcy. An unhappy novice in western exploration who was ordered to New Mexico from a pleasant assignment as superintendent of lighthouse construction near Monroe, Michigan, Simpson identified and recorded prominent landmarks to guide later wagon trains. When Marcy turned back toward Texas, Simpson stayed in New Mexico and reported for duty with Lieutenant Colonel John N. Washington's Ninth Military Department. [6]

|

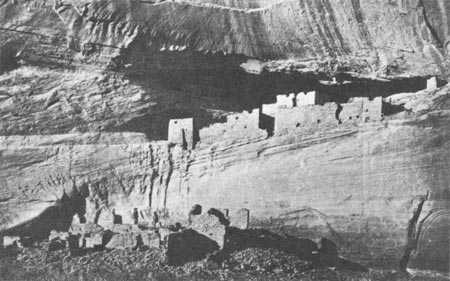

| Ruins in the Canyon de Chelly. |

Shortly after his arrival, Simpson met topographer Edward (Ned) Kern and his artist brother Richard. The Kerns had a grisly story to tell. Respected naturalists and members of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, both were drawn irresistibly by the West. They and their brother Benjamin, a physician, had jumped at the chance to accompany Frémont on a privately financed railroad survey in 1848. As autumn became winter, the invigorating season of fieldwork turned into the grimmest of disasters. Lost, chilled to the bone, and so hungry they tried to trap mice, Frémont and his men stumbled blindly through slashing blizzards in the San Juan Mountains near the headwaters of the Rio Grande. The mules died first, then the men began to succumb. In despair, Frémont relinquished command, and it became every man for himself. The Kerns stuck together and stumbled upon relief in late January. Weak and almost deranged, they wept at the sight of bread and meat. Eleven of their thirty companions never escaped the white horror. [7]

There was still more to the tale. Frémont cast all blame for the disaster on guide Bill Williams, and even accused him of cannibalism: "In starving times," Frémont said, "no man who knew him ever walked in front of Bill Williams." [8] The unfortunate Williams never had the chance to defend himself. In March, 1849, as he and Ben Kern made their way back toward the mountains to recover possessions cached during the winter, a band of Utes surprised and killed both. [9] When Ned and Richard met Simpson, they had little left beside their great talents and sorrowful memories.

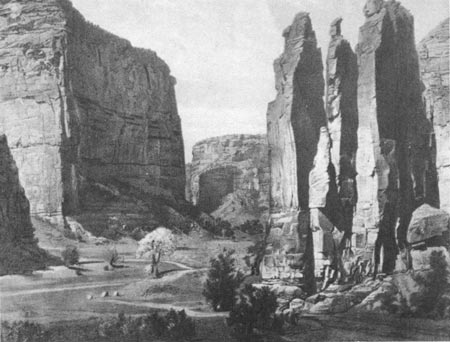

Simpson could do nothing to blot out the memories, but he could offer them work. Assigned to guide Colonel Washington's expedition against the Navahoes and survey the country traversed by the column, Simpson hired Ned as topographer and Dick as artist. The Navahoes, called "the Earth People" in their own language and now famous as shepherds and horsemen, silversmiths and weavers, had achieved another kind of renown by the end of the Mexican War. The most feared raiders on the New Mexican plateau, they terrorized white settlements as well as their Zuni and Hopi neighbors. [10] Colonel Washington intended to strike deep into their canyon strongholds and end the tribe's career as the scourge of New Mexican settlements.

|

| The sandstone walls of Canyon de Chelly. |

Across the continental divide and up the Rio Chaco, Simpson and his assistants rode with Washington and his men, yet barely seemed part of the expedition. In the chasms of the Chaco, they became absorbed in investigating the ruins of ancient Indian pueblos, large prehistoric communities of stone, mortar, and wood, incredibly assembled with only stone tools by unknown builders. In a ten-mile strip of the canyon floor, Simpson found twelve large community houses, each capable of housing several hundred to a thousand residents, as well as many smaller structures. He estimated that one of the larger ones, which he dubbed Chettro Kettle (now written Chetro Ketl), was built of over thirty million pieces of stone, a guess that has been revised to fifty million by modern archaeologists. While Richard Kern sketched and mapped the canyon, Simpson moved delightedly from Chetro Ketl to Pueblo Bonito, then to Pueblo del Arroyo, visiting the accessible rooms, counting, measuring, and describing his discoveries. Finally he had to stop and rejoin the expedition. He still worked for Colonel Washington. [11]

Simpson's discoveries in Chaco Canyon and later in Canyon de Chelly were of lasting scientific importance. In a region then unknown to Anglo-Americans, he found one of the most important archaeological sites in the United States. Accounts of the pueblo cultures still begin with reference to Simpson's discoveries and Kern's drawings. While pushing back the physical frontier, Simpson showed the way to new scientific and cultural horizons. [12]

In contrast to Simpson's successful probe of the canyons, Washington's punitive foray turned into a tragic farce. At a time when Navahoes and Mexicans stole countless mounts from each other, the soldiers killed the aged, rheumatic Navaho chief Narbona for the theft of one horse. After the shooting, the Indians signed the treaty proffered by Washington, but only to make him go away. He succeeded only in adding to the growing hostility of the Navahoes before he and his troops withdrew. [13]

In September, 1851, Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves of the Topographical Engineers continued the reconnaissance of New Mexico. Seeking the westward wagon road that Simpson believed feasible from Albuquerque to the Colorado and perhaps all the way to Los Angeles, Sitgreaves, Lieutenant John G. Parke, Richard Kern, and an infantry escort went around the San Francisco Mountains and across the great Colorado River to California. With nineteen years of service, thirteen of them in the Topographical Engineers, Sitgreaves made a good teacher for Parke, also a topog but in the West for the first time. Although harrassed by Mohave and Yuma warriors, the party reconnoitered the slightly known country between Canyon de Chelly and the Colorado. Sitgreaves disliked the Southwest even more than Simpson and, in his twenty-page report, summed up the 250-mile expanse between Bill Williams Mountain and San Diego in a single sentence: "The whole country traversed from the San Francisco mountains was barren and devoid of interest." [14]

|

| Three Mohave Indians. |

After Sitgreaves's expedition came a period of road surveys and construction. In 1854, Congress voted appropriations for improvement of territorial roads, some cut by arroyos and others scarcely more than bridle paths, but all little better than the open country they crossed. Captain Eliakim P. Scammon of the Topographical Engineers, once an assistant in the preparation of Nicollet's map of the Mississippi drainage system, took charge of the work. During two years in Santa Fe, Scammon spent most of the money but made very little progress on the roads. Unschooled in road building and bewildered by the complexities of the bookkeeping, Scammon was finally dismissed from the service for failure to account properly for $350 in public funds. When Captain John N. Macomb took over in 1856, the work began in earnest. [15]

Almost halfway through a military career that spanned fifty years, Macomb wasted no time getting started. After surveying the potential routes, he hired civilian crews for the actual construction. Normally, this involved merely grading and widening paths for use by wagons. Some of the roads required more extensive improvement, and Macomb's work crews bridged gullies, paved steep grades with finely crushed rock (called macadam after the developer of the technique, Scottish engineer John L. McAdam), and erected dry masonry walls to shield the exposed sides of mountain roads from flash floods. By the time he was transferred in 1859, Macomb completed several major routes. Together with trails examined by earlier explorers, the Macomb roads formed the basis for New Mexico's highway and railroad system. [16]

|

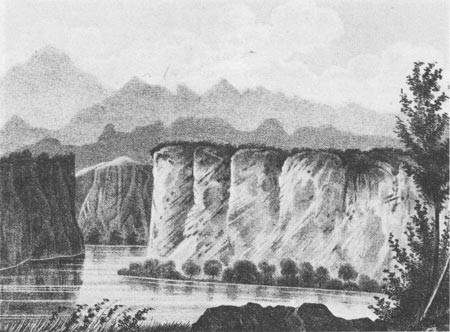

| The view from Captain Sitgreaves' camp on the Colorado. |

Establishment of communications with California was the object of much of the work topogs did in Texas and New Mexico after the Mexican War. The 1848 discovery of gold in the American River triggered a wave of emigration to the new Golconda. While many gold-seekers found their way across the central plains and the Great Basin with the help of Frémont's map, others crossed the Southwest with Emory's map in hand. Emory and Amiel Whipple, at work on the Mexican boundary in 1849, saw many parties, some suffering terribly, along the southern route. The commander of the Tenth Military Department authorized Emory to give supplies to the needy and directed him to locate a military post at the junction of the Gila and Colorado rivers. Known first as Camp Yuma and later given permanent status as a fort, Yuma protected travelers along the trail to California throughout the gold rush years. [17]

Yuma was the very definition of an isolated frontier outpost. In the middle of a parched wasteland populated by unfriendly Indians, where the mean December temperature was a blistering 92°F, the camp seemed more a place of banishment than an ordinary post. Some claimed hens laid hard-boiled eggs there. Lieutenant George H. Derby, a topog assigned in 1850 to ascertain the navigability of the Colorado up to Yuma, said a villainous soldier who died there and went straight to hell telegraphed back for his blankets. [18] Later, in one of his humorous essays on astronomy, published under the pseudonym John Phoenix, Derby compared the relative desirability of establishing posts at Yuma and on the planet Mercury:

[Mercury] receives six and a half times as much heat from the sun as we do; from which we conclude that the climate must be very similar to that of Fort Yuma, on the Colorado River. The difficulty of communication with Mercury will probably prevent its ever being selected as a military post, though it possesses many advantages for that purpose, being extremely inaccessible, inconvenient, and doubtless, singularly uncomfortable. [19]

Hoping to reduce the tremendous expense and uncertainty of supplying the post overland from San Diego, the Army sent Derby up the Colorado aboard an ocean-going schooner. Although he was a capable veteran of the Mexican War, the Missouri River frontier, and the California goldfields, Derby was primarily known for his humor. Even during his years at West Point, among his classmates George B. McClellan and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, he had been irrepressible. When, for example, a professor asked him the proper course of action as commander of a beseiged fort sure to fall in forty-five days, Derby replied, "I would march out, let the enemy in, and at the end of forty-five days, I would change places with him." [20] Matching his brash wit with solid ability, Derby completed his reconnaissance of the Colorado from its mouth at Guyamas on the Gulf of California to Yuma. Thereafter, the small post astraddle the southern emigrant road to California was assured of regular provisions. [21]

|

| "The Ass-sault," a tactical innovation by John Phoenix. When the recoiling artillery drove the mule forward, it would respond by charging backward—toward the enemy. |

Three Topographical Engineers, Captain William H. Warner and Lieutenants Robert S. Williamson and Derby, performed a variety of tasks in California. Warner, Chief Topographical Engineer of the Tenth Military Department after recovering from wounds sustained at San Pasqual, began his work in 1847. He made extensive examinations of routes connecting San Diego and San Francisco before leading an expedition east into the Sierra Nevada with Lieutenant Williamson.

In August, 1849, Warner and Williamson left Sacramento in quest of a railroad route through the mountains to the Great Basin. Guided by Francois Bercier, an old voyageur for the Hudson's Bay Company, and accompanied by eleven civilian assistants they rode northward up the Sacramento toward the country of the Klamaths, who four years previously had attacked Frémont and killed several of his men. Warner left Williamson and most of his infantry escort near Deer Creek Pass and followed the Pit River to its source near Goose Lake in the northeastern corner of California, where he found his railroad pass. [22]

|

| George H. Derby. National Archives. |

When he and Williamson reached the eastern edge of the mountains the great surge of Argonauts was about to descend on California. Several gold-seekers, coming over the mountains on the Lassen Trail, told the surprised topogs that ten or twenty thousand more were behind them. The flood, which had already swept over the Platte River road, would soon inundate California. The gold rush was on.

Warner and his party were making their way back toward Sacramento along Frémont's 1844 route when disaster struck. On September 26, as he and Bercier nudged their mounts up a steep hill, Pit River Indians surprised and killed them. Lieutenant Williamson filed this report:

. . . a party of about twenty-five Indians, who had been lying in ambush behind some large rocks near the summit, suddenly sprang up and shot a volley of arrows into the party. The greater number of the arrows took effect upon the Captain and the guide, and both were mortally wounded. The Captain's mule turned with him, and plunged down the hill; and having been carried about two hundred yards, he fell from the animal dead. [23]

Williamson managed to recover Warner's notebooks before he withdrew to Sacramento to compile a report and map.

Not all topog assignments in California ended in such tragedy. In 1853, when silt from the San Diego River threatened to ruin San Diego's fine harbor, Lieutenant Derby left a staff job in San Francisco to supervise improvement of the channel. He departed from the Golden Gate in typical Derby style. At dinner in a hotel before he left, he watched the innkeeper carving a roast of veal into small pieces, because, as his host explained, "there is but little of it, and I want to make it go as far as possible." "In that case," Derby replied, "I'll take a large piece. I think I can make it go as far as anybody; I am going to San Diego." [24]

At San Diego, or Sandyago as he sometimes spelled it, Derby the topog took a backseat to his alter ego, humorist John Phoenix. While the topog worked on the diversion of the river, the humorist had a field day writing for the San Diego Herald, which the editor once turned over to him for two weeks. When work on the harbor proved frustrating, Phoenix told his readers that Derby "was sent out from Washington . . . 'to dam the San Diego River,' and he informed me with a deep sigh and melancholy smile that he had done it (mentally) several times since his arrival." Always dedicated to keeping his readers abreast of engineering developments, Phoenix issued the following statement: "The report that Lieutenant Derby has sent to San Francisco for a lathe, to be used in turning the San Diego River is, we understand, entirely without foundation." [25] When Derby and Phoenix left San Diego in 1855, they left not only an incomplete dam that was partially washed away by a storm the following year, but also an enduring contribution to American humor.

While Warner, Williamson, and Derby toiled in California, other topogs worked in the Great Basin. Two major expeditions probed the region during the years following the Mexican War. Captain Howard Stansbury, commissioned in 1838 after more than a decade as a civil engineer for the Topographical Bureau, led the first reconnaissance. His assistant, Lieutenant John W. Gunnison, entered the service in 1837 after graduating near the top of his West Point class. Neither had any experience in western exploration, when, on the last day of May, 1849, they left Fort Leavenworth to explore the Great Salt Lake and its valley.

In mid-October Stansbury, Gunnison, and a small band of hardy mountaineers stood on the shore of the lake, preparing for their journey around the inland sea. The old-timers warned against the trip. It was nearly impossible in any season, they said, but the oncoming winter would make the trek even harder. And the Shoshones north of the lake, still mourning the men murdered while trying to defend their women from assault by California-bound whites, might dispatch those explorers not killed by the brutal march. The time seemed wrong. Nevertheless, on October 19, Stansbury set out on the difficult mission. [26]

Although the trip would take over two weeks and exact its toll in hardship and suffering, Stansbury approached the lake eagerly. He marvelled at the "clear and calm" waters that "stretched far to the south and west," but was even more impressed with the exotic qualities of the vista:

. . . the dreamy haze hovering over this still and solitary sea threw its dim, uncertain veil over the more distant features of the landscape, preventing the eye from discerning any one object with distinctness, while it half revealed the whole, leaving ample scope for the imagination of the beholder. The stillness of the grave seemed to pervade both air and water, and excepting here and there a solitary wild duck floating motionless on the bosom of the lake, not a living thing was to be seen. [27]

After the wonder and awe came torment and pain. Several times the party went entire days without water. In addition, the plain to the north and west of the lake proved extremely difficult to cross. The first part of the route passed over an expanse of dried mud, sparkling with salt crystals. For a while Stansbury's mules crossed the salt flats as they would a sheet of ice. Then rain turned the firm crust into a nearly impassable mire and made travel extremely difficult. [28]

Captain Stansbury completed the reconnaissance on November 7, when he returned to Salt Lake City. Proud of his achievement, he boasted that his detachment was "the first party of white men that ever succeeded in making the entire circuit of the lake by land." He described the region bordering the lake as "an immense level plain, consisting of soft mud, frequently traversed by small meandering rills of salt and sulphurous water, with occasional springs of fresh, all of which sink before reaching the lake." [29]

Snow began to fall as winter set in and made further work impossible. Stansbury established his cantonment in Salt Lake City, and passed the cold months learning about the Latter-Day Saints. He devoted a large portion of his report to a discussion of the development of the Mormon community, which he found to be "a quiet, orderly, industrious, and well-organized society. . . ." [30]

Gunnison included his observations on the Mormons in a book entitled The Mormons, Or Latter-Day Saints in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. He told his inquisitive countrymen a great deal about the community, explaining land use and education as well as the controversial practice of plural marriages. He praised what he found praiseworthy and criticized what he considered distasteful. He was, for example, impressed with the free, well-attended public schools but appalled by the profane language of children on the streets. At a time when discussion of the Mormons generated great passions, both Gunnison and Stansbury took unusually calm and fair positions. [31]

When the topogs resumed active operations in the spring, Captain Stansbury decided to supplement his trip around the lake with an exploration by water. His men built a small wooden sailboat, which they named Salicornia, or Flower of Salt Lake, but which soon came to be known as the Sally. They spent parts of two months on the water, accumulating data for their map. Stansbury was deeply affected by the vastness and the deathlike quiet of the lake. He recorded his impressions of a solitary night at the helm while his crew slept:

I shall never forget this night. The silence of the grave was around us, unrelieved by the slightest sound. Not the leaping of a fish nor the solitary cry of a bird was to be heard, as, in profound darkness, the boat moved on, plunging her bow into the black and sullen waters. . . . The sense of isolation from everything living was painfully oppressive. Even the chirp of a cricket would have formed some link with the world of life; but all was stillness and solitary desolation. [32]

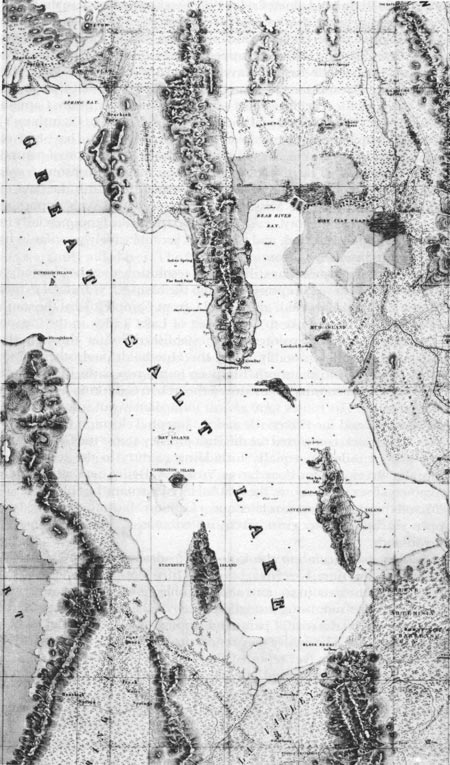

In August Stansbury and Gunnison left Salt Lake City for the return trip to Fort Leavenworth. Their trail over the Green River and then across the Laramie Plains and along Lodge Pole Creek to its mouth in the South Platte proved to be the shortest and easiest path from Salt Lake City. The discovery of this route, parts of which were later used by the Pony Express and the Union Pacific Railroad, capped a successful expedition, in which Stansbury became the first to travel around the Great Salt Lake and recognize the Great Basin as a prehistoric lakebed. In addition to his major topographical achievements—his successor in the Basin, Captain Simpson, said "it has been a gratification to me to find that [Stansbury's] report and map have represented the country so correctly and have been of much service to me...."—Stansbury accumulated a collection of natural history specimens so large that Spencer Baird of the Smithsonian was prompted to claim that "no government expedition since the days of Major Long's visit to the Missouri has ever presented such important additions to natural history...." [33] His report, published commercially in the United States, England, and Germany, became widely popular in its own time and remains a frontier classic. [34]

|

| A portion of Howard Stansbury's map, showing the Great Salt Lake. National Archives. |

Some important questions still awaited resolution after the Stansbury Gunnison expedition. Simpson went into the basin ten years later to find a wagon road through Utah and Nevada, from Camp Floyd at the south end of the Great Salt Lake to Genoa east of Lake Tahoe in the Carson River valley. Earlier explorers had established routes through the northern basin, most notably along the Humboldt, and other routes skirted the region to the south. Simpson found two paths through the center of the arid country that reduced the trek to California by over two hundred miles. His routes were almost immediately put into use by the Pony Express and the Placerville and St. Joseph Telegraph Company. [35]

While Simpson completed the difficult journey across the Great Basin, other topogs toiled in equally forbidding country to the south. The Colorado River, explored as far as Yuma by Derby, was still largely unknown. Two expeditions, the first led by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives in 1857 and the second two years later under Captain Macomb, examined the upper reaches of the great river, its tributaries, and the fantastic canyonlands.

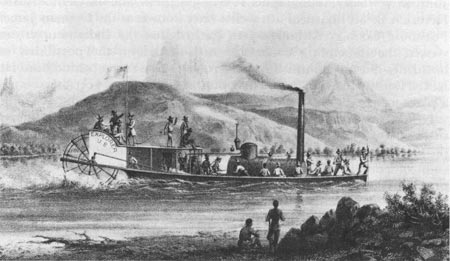

The Ives party came to the Colorado to determine its navigability upstream from Yuma. Ives's men brought a fifty-foot-long iron steamer to the mouth of the river in sections and assembled it before a curious crowd of Indians. After mounting a small howitzer at the bow, members of the party gave the boat a coat of paint and printed "Explorer" boldly across the wheelhouse. The boiler was tested successfully on Christmas day, 1857. Five days later Ives reported that "with a shrill scream from the whistle the 'Explorer' started out into the river, and in a moment was shooting along upon the tide with a velocity that made the high bank seem to spin as we glided by." So began the expedition which culminated in the first recorded exploration of the floor of the Grand Canyon. [36]

Fed by driftwood scavenged by the crew and co-operative Indians, the Explorer chugged upriver. At Fort Yuma Ives picked up the members of his party who had come overland from San Diego, including geologist John S. Newberry, topographer F. W. Egloffstein, and the German artist Heinrich B. Mollhausen, a novelist later known as the German James Fenimore Cooper. Although Ives learned that the Indians upstream viewed the impending encroachment with alarm, the possibility of hostilities did not diminish his eagerness to put Yuma behind him. He lacked Derby's flair but shared his opinion of the post: "Fort Yuma is not a place to inspire one with regret at leaving." [37]

Ives did not easily escape from Yuma. Two miles upstream the Explorer stuck on a sandbar. The entire party toiled for over four hours, unloading the ship and forcing it into deep water. The operation took place in plain sight of Yuma, and Ives ruefully noted that "this sudden check on our progress was affording an evening of great entertainment to those in and out of the garrison." [38]

The unfriendly interest of the Yuma Indians who watched the Explorer's progress after it churned past the Chocolate Mountains, inadvertantly aided Ives. The vessel's inventor and pilot, sharp-eyed A. J. Carroll, quickly grasped the coincidence between their presence and bad stretches of river. Whenever he saw them gathered he slowed the engine in expectation of the sandbar that inevitably followed. Thus guided, Ives went up toward the head of navigation, hoping to find a convenient supply route via the Colorado to Utah. War with the Mormons was already imminent and the provisioning of forts and even an army in the field was vitally important to the War Department. So it was not only in the interest of science that the Explorer made its way through the "low purple gateway" into Mohave Canyon. [39]

Once through the canyon and into the country of the Mohaves, Ives found friendlier guides. To his delight, he located two Indians who had guided Lieutenant Whipple on his Pacific railroad survey in 1854. Whipple had once been reviled by an escort officer for his interest in the Indians, but his kindness to the Mohaves Cairook and Ireteba paid great dividends to Ives. Both agreed to go upriver and, although Cairook turned back after two days, Ireteba remained with the expedition all the way to Black Canyon. [40]

Provisions ran out in the Mohave country and the party was forced to adopt the Indian diet of corn, beans, and river water. Ives hated the food and longed for a well-salted soup made with dog or mule meat. Geologist Newberry also loathed the coarse, plain fare which he thought consisted mainly of sand rather than corn and beans. The sand, he complained to fellow scientist Ferdinand Hayden, was everywhere, in his plate, his bed, and his clothes. [41]

Soon the party reached the head of navigation in Black Canyon, where the Colorado abruptly bent to the east. They examined the canyon in a skiff driven by oars and sails and climbed onto the plateau to locate a connection with the Mormon road to Utah. Then they turned back in the steamer and shot the rapids coming out of Black Canyon. Just downstream a runner from Fort Yuma met them with letters, papers, and the welcome news that a packtrain of supplies approached, promising all a quick change of diet.

|

| The Ives expedition bound for Black Canyon. Library of Congress. |

Freshly provisioned and well-rested, Ives sent Carroll and the Explorer back to Yuma and headed east with two Hualapais Indian guides. A third tribesman who visited the party was lucky to get away alive. The overzealous Möllhausen, fascinated by what he considered to be this Indian's extraordinary ugliness, wanted to take the poor man east—as a zoological specimen pickled in alcohol. Lieutenant Ives overruled Möllhausen, and the party rode eastward on muleback to intersect the Colorado at Grand Canyon.

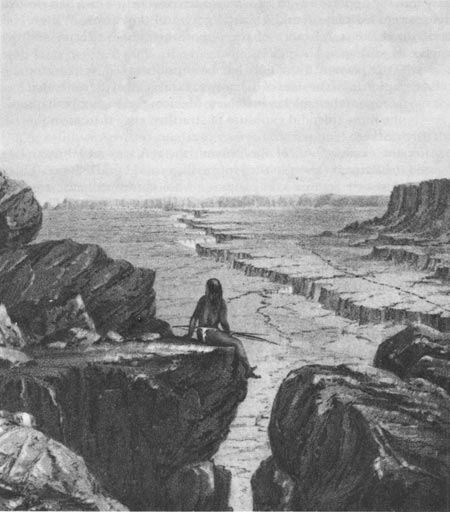

After they reconnoitered the plateau, the party began the perilous descent to the canyon floor. Under a blazing sun they nudged their mules down a narrow path cut into the cliffs by Indians. As they eased their way down, the men seemed to Ives "very much like a row of insects crawling upon the side of a building...." On a path barely wide enough for a mule and its rider, Ives's mount trod "within three inches of the brink of a sheer gulf a thousand feet deep." Finally they could ride no more. With a steep cliff at one shoulder and the abyss on the other side, Ives's head spun with dizziness. Slowly, very carefully, he dismounted and led his mule down. Others became even giddier, and "were obliged to creep upon their hands and knees, being unable to walk or stand." [42] Their slim trail ended on a broad ledge. Beyond was only a series of footholds cut in cracks and fissures, "a desperate trail, but located with a good deal of skill." With no water for the animals nearer than a series of pools thirty miles away, the party turned back.

After sending, three men for water, Ives and fifteen others tried again, this time on foot. They passed the ledge which marked their earlier progress to within fifty feet of the bottom, where a rickety ladder leaning against the canyon wall offered a way to the floor. Topographer Egloffstein made his way gingerly down the ladder, which collapsed just as he touched bottom. His companions retrieved him by means of a rope made from the slings of their rifles. Unable to complete the return climb before nightfall, the small exploring party huddled on the trail, "deeper in the bowels of the earth than we had ever been before, surrounded by walls and towers of such imposing dimensions that it would be useless to attempt describing them..." [43] When day broke, they resumed their trek, and returned to camp thirty perilous miles and twenty-four hungry hours after they began the descent.

|

| The Colorado River with the eastern edge of the Grand Canyon in the distance. |

Ives described the Grand Canyon region as completely worthless. While proudly claiming that his was the first party of whites into the canyon, he confidently asserted that it would also be the last. Geologist Newberry, on the other hand, found the canyonlands far from useless. The exploration gave him the opportunity to see what no scientist before him had viewed, the vast eroded plateau and gigantic gorges of the canyon. [44] Even Ives understood the significance of the opportunity for Newberry and the science of geology:

This plateau formation has been undisturbed by volcanic action, and the sides of the canyon exhibit all of the series that compose the tablelands of New Mexico, presenting perhaps the most splendid exposure of stratified rock there is in the world. [45]

After the examination of the canyon, the rest was anticlimax. Ives crossed the Painted Desert to the Hopi villages and Fort Defiance. There he bid farewell to his companions, who continued east to Fort Leavenworth. He took a more circuitous route by way of Santa Fe and El Paso to the west coast and a New York-bound steamer.

Ives never saw the Colorado again, but Newberry returned in 1859 with Captain Macomb. They came overland from Santa Fe, tracing the drainage of the San Juan River, then riding through the canyon country north of the intersection of the Green and Grand rivers. Macomb shared Ives's opinion of the canyonlands: "I cannot conceive of a more worthless and impracticable region than the one we now found ourselves in." [46] Indeed, for almost five hundred miles, the Colorado flowed 3,000 to 6,000 feet below the "abrupt, frequently perpendicular crags and precipices" of the plateau above. Newberry called the region "valueless to the agriculturist; feared and shunned by the emigrant, the miner, and even the adventurous trapper...." But he acknowledged that for him the plateau was a "paradise" because "nowhere on the earth's surface, so far as we know, are the secrets of its structure so fully revealed as here." [47]

Macomb and a small detachment escorted Newberry down to the river from a base camp at Ojo Verde. On their descent they passed through country "everywhere deeply cut by a tangled mass of canyons, and thickly set with towers, castles, and spires, of most varied and striking forms; the most wonderful monuments of erosion which our eyes, already experienced in objects of this kind, had beheld." Grasping for something familiar with which to compare the marvels, Newberry asked readers to imagine "the island of New York thickly set with spires like that of Trinity Church, but many of them full twice its height." [48]

The scientist did not go into the canyon just to indulge in literary flights. His close observations of the walls enabled him to characterize the entire area, where his predecessors had merely catalogued geological features. His work called attention to the value of careful analyses of single mountain ranges or peaks, known as key studies, as a way to understand the basic principles of a region's creation. Geographically and geologically Newberry and Macomb revealed a new and unknown region to their countrymen. [49]

Years before John Wesley Powell's epic journey downsteam from the upper reaches of the Green through the Grand Canyon in 1869, the combined efforts of Derby, Ives, and Macomb gave the nation a substantial amount of information about the Colorado. Newberry in particular made significant geological contributions. Topographer Egloffstein, who descended the rickety ladder to the Grand Canyon floor, accurately depicted the region in a contour map of his own design, which made the mountains stand out in sharp relief. [50] While navigating the river and probing the fantastic chasms of one of American's spectacular wonderlands, the engineer parties made significant contributions to the development of science.

The southwestern reconnaissance served the national concern with the conquest of the continent extremely well. The explorations and road surveys yielded important practical results, among them roads, railroad passes, and telegraph routes. Improvement of harbors, location of forts, and guidance of Indian expeditions offered other utilitarian services. Whether hard and dull like the Texas road surveys, or exciting and exotic like Ives's descent of the Grand Canyon, the expeditions brought back indispensable data on resources, climate, and topography.

While easing the way for the physical growth of the nation, the southwestern reconnaissance of the Topographical Engineers had significant scientific consequences. Simpson's archaeological discoveries, Newberry's geological work, and Stansbury's analysis of the Great Basin's origins all contributed to a deeper comprehension of the nature of the continent. These insights into the human and natural history of North America, combined with the diverse practical contributions to westward expansion, highlighted the time as the heyday of the topogs, their busiest and most fruitful period.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

schubert/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 17-Mar-2005