|

BIG BEND

The Impact of Human Use Upon the Chisos Basin and Adjacent Lands NPS Scientific Monograph No. 4 |

|

CHAPTER 5:

Present Vegetation of the Basin

Methods

Since the vegetation of the Chisos Basin has not been previously investigated, this study attempted to sample and compare the vegetation on various substrates and on opposing exposures. Because of the rugged terrain and lack of time, only a cursory quantitative investigation could be made of the existing vegetation. Emphasis was placed upon the major vegetation types in the northern portion of the basin, where a total of 18 sites was sampled (Table 1, Fig. 2.).

The method used to sample the vegetation was to establish a line 100 ft long and record species and crown cover for every individual rooted or casting cover within 1.5 ft of the line. From these contiguous plots (10 x 3 ft) data were obtained which were used to calculate relative density, relative frequency, and relative cover values for each species. By summing the three relative values for each species in each transect, an Importance Value (IV) was obtained. This value permits the ranking of site species and was used in establishing the three formation classes.

A summary of the results for each site is presented in Table 4. The two dominant plants of each life-form in the three vegetation types are presented along with their IV. The sites are listed in each formation class from what is thought to be the most mesic to the most xeric. The life-form, generic name, common name, and a more complete list of the species are found in Table 6. The number of X's in a particular column is dependent upon the commonness of the species in the formation. One X indicates only sighting or collection in the formation, two signifies an IV of less than 40, and three, greater than 40. The list is by no means complete, but represents only those species sampled in transects or collected as vouchers in other studies. A total of 171 species is listed and over 300 specimens are deposited as vouchers in the Bebb Herbarium, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Okla.

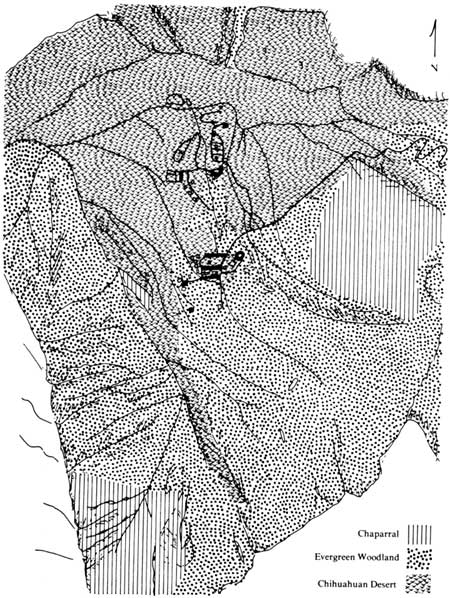

The distinction of three formation classes is based upon the general physiognomy of vegetation, distribution, and species assemblages. More extensive field work in the mountains could reveal negation or added support. The three formations distinguished are: Evergreen Woodland Formation (EWF), Chaparral Formation (CF), and Chihuahuan Desert Formation (CDF, Fig. 3). A discussion of each formation will follow.

|

| Fig. 3. Map of present vegetation in the basin. |

Table 6. Complete list of the plants encountered in the Chisos Basin study. The species, with common names, are grouped according to life-form and frequency in the formations (X, sighted or collected: XX. IV less than 40: XXX. IV greater than 40).

| Species | EWF | CF | CDF |

| Trees | |||

| Fraxinus cuspidata Torr. (Fragrant ash) | X | ||

| Juniperus deppeana Steud. (Alligator juniper) | XX | ||

| Juniperus pinchoti Sudw. (Redberry juniper) | XX | ||

| Juniperus flaccida Schlecht. (Drooping juniper) | XX | ||

| Arbutus texana Buckl. (Texas madrone) | XX | ||

| Pinus cembroides Zucc. (Mexican pinyon) | XXX | ||

| Quercus gravesii Sudw. (Graves oak) | XXX | X | |

| Quercus emoryi Torr. (Emory oak) | XXX | X | XX |

| Quercus grisea Liebm. (Gray oak) | XX | X | X |

| Prosopis glandulosa Torr. (Honey mesquite) | XX | X | |

| Quercus intricata Trel. (Dwarf oak) | XX | ||

| Quercus pungens Liebm. (Sandpaper oak) | XX | ||

| Celtis reticulata Torr. (Netleaf hackberry) | X | ||

| Acacia roemeriana Scheele (Roemer acacia) | X | ||

| Ungnadia speciosa Endl. (Mexican buckeye) | X | ||

| Diospyros texana Scheele (Texas persimmon) | X | ||

Shrubs | |||

| Foresriera neomexicana (New Mexico forestiera) | X | ||

| Ceanothus greggi Gray (Desert ceanothus) | X | ||

| Prunus serotina Ehrhart (Southwestern chokecherry) subsp. virens (Woot. & Standl.) McVaugh | X | ||

| Aloysia wrightii (Gray) Heller (Wright aloysia) | XX | ||

| Isocoma coronopifolia (Gray) Greene | XX | ||

| Bouvardia ternifolia (Cav.) Schlecht. (Scarlet bouvardia) | XX | ||

| Rhamnus betulaefolia Greene (Birchleaf buckthorn) | XX | ||

| Salvia regla Cav. (Mountain sage) | XX | ||

| Garrya lindheimer Torr. (Lindheimer silktassel) | XX | X | |

| Rhus aromatica Ait. (Skunkbush) var. flabelliformis Shinners | XX | XX | |

| Berberis haematocarpa Woot. (Red barberry) | X | X | |

| Larrea tridentata Cav. (Creosotebush) | X | X | XX |

| Viguiera stenoloba Blake (Skeleton goldeneye) | XX | XX | XX |

| Cercocarpus montanus Raf. (Silverleaf mountainmahogany) var. argenteus (Rydb.) F. L. Martin | XX | XXX | XX |

| Rhus virens Lindh. ex Gray (Evergreen sumac) | XX | XX | XXX |

| Zexmenia brevifolia Gray (Shorthorn zexmenia) | XX | ||

| Aloysia lycioides Chain. (Whitebrush) | XX | X | |

| Mimosa biuncifera Benth. (Catclaw mimosa) | XX | XX | |

| Acacia constricta Benth. ex Gray (Mescat acacia) | XXX | XX | |

| Condalia lycioides (Gray) Weberb. (Southwest condalia) | X | X | |

| Condalia spathulata Gray (Knifeleaf condalia) | X | X | |

| Ptelea trifoliata L. (Hoptree) | X | X | |

| Parthenium incanum H.B.K. (Mariola) | X | X | |

| Fraxinus greggi Gray (Gregg ash) | XXX | XXX | |

| Glossopetalon spinescens Gray (Spiny greasebush) var. mexicana (Ensign) St. John | XX | XX | |

| Ephedra nevadensis Wats. (Boundary ephedra) var. aspera (Engelm.) L. Benson | XX | ||

| Krameria glandulosa Rose & Painter (Range ratany) | XX | ||

| Dalea frutescens Gray (Black dalea) | XX | ||

| Leucophyllum minus Gray (Big Bend silverleaf) | X | ||

| Eysenhardtia texana Scheele (Texas kidneywood) | X | ||

| Vauquelinia angustifolia Rydb. (Slimleaf vauquelinia) | X | ||

| Baccharis glutinosa (Ruiz & Pavon) Pers. (Seepwillow) | X | ||

| Rhus microphylla Engelm. ex Gray (Littleleaf sumac) | X | ||

| Anisacanthus insignis Gray (Dwarf anisacanth) | X | ||

| Atriplex canescens (Pursh) Nutt. (Fourwing saltbush) | X | ||

| Sophora secundiflora (Ort.) Lag. ex DC. (Mescalbean) | X | ||

| Dicraurus leptocladus Hook. (Thinbush) | X | ||

Succulent-Semisucculents | |||

| Agave chisoensis C. H. Mueller (Chisos agave) | X | ||

| Nolina erumpens (Torr.) Wats. (Foothill nolina) | XX | XX | |

| Agave scabra Salm-Dyck | XX | XX | |

| Dasylirion leiophyllum Engelm. (Smooth sotol) | XX | XX | XX |

| Opuntia engelmannii Parry (Engelmann pricklypear) | XX | XX | XX |

| Agave lecheguilla Torr. (Lechuguilla) | XXX | ||

| Opuntia imbricata Haw. (Cholla) | X | ||

| Opuntia kleiniae DC. (Candle cholla) | X | ||

| Opuntia leptocaulis DC. (Pencil cholla) | X | ||

Grasses | |||

| Cenchrus incertus Curtis (Sandbur) | X | ||

| Eragrostis barrelieri Daveau. (Mediterranean lovegrass) | X | ||

| Andropogon gerardi Vitm. (Big bluestem) | X | ||

| Stipa eminens Cav. (Southwestern needlegrass) | XX | ||

| Aristida orcuttiana Vasey (Single threeawn) | XX | ||

| Aristida divaricata Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. (Poverty threeawn) | XX | ||

| Stipa tenuissima Trin. (Finestem needlegrass) | XXX | ||

| Piptochaetium fimbriatum (H. B. K.) Hitchc. (Pinyon-ricegrass) | XXX | ||

| Eragrostis intermedia Hitchc. (Plains lovegrass) | XX | X | |

| Bouteloua gracilis (Willd. & H. B.K.) Lag. ex Gruff. (Blue grama) | XXX | XX | X |

| Muhlenbergia emersleyi Vasey (Bullgrass) | XXX | XX | XX |

| Bouteloua curtipendula (Michx.) Torr. (Sideoats grama) | XXX | XXX | XXX |

| Bothriochloa barbinodis (Lag.) Herter (Cane bluestem) | XX | XX | XX |

| Aristida glauca (Nees) Walp. (Blue threeawn) | XX | XX | XX |

| Lycurus phleoides H.B.K. (Wolftail) | X | X | XX |

| Setaria macrostachya H.B. K. (Plains bristlegrass) | XX | X | |

| Hilaria mutica (Buckl.) Benth. (Tobosagrass) | XX | X | |

| Muhlenbergia rigida (H.B.K.) Kunth. (Purple muhly) | XX | XX | |

| Sorghum halpense (L.) Pers. (Johnsongrass) | X | X | |

| Bouteloua hirsuta Lag. (Hairy grama) | X | XXX | |

| Schizachyrium scoparium (Michx.) Nash (Little bluestem) | XXX | ||

| Heteropogon contortus (L.) Beauv. (Tanglehead) | XX | ||

| Bouteloua breviseta Vasey (Chino grama) | XX | ||

| Bouteloua eriopoda (Torr.) (Black grama) | XX | ||

| Panicum hallii Vasey (Halls panicum) | X | ||

| Panicum obtusum H.B.K. (Vinemesquite) | X | ||

| Bromus unioloides (Willd.) H. B. K. (Rescuegrass) | X | ||

| Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. (Bermudagrass) | X | ||

| Muhlenbergia porteri Scribn. (Bush muhly) | X | ||

| Erioneuron pulchellum (H.B.K.) Tateoka (Fluffgrass) | X | ||

| Erioneuron grandiflorum (Vasey) Tateoka (Large flowered tridens) | X | ||

| Sporobolus cryprandrus (Torr.) Gray (Sand-dropseed) | X | ||

| Leptochloa dubia (H.B.K.) Nees (Green spangletop) | X | ||

| Panicum bulbosum H.B.K. (Bulb panicum) | X | ||

| Aristida ternipes Cav. (Spidergrass) | X | ||

| Digitaria californica (Benth.) Henr. (Arizona cottontop) | X | ||

| Chloris virgata Swartz (Showy chloris) | X | ||

| Echinochloa crusgalli (L.) Beauv. (Barnyardgrass) | X | ||

Herbs | |||

| Conyza sophiaefolia H.B.K. (Leafy conyza) | X | ||

| Heliopsis parvifolia Gray (Mountain heliopsis) | X | ||

| Euphorbia villifera Scheele (Hairy euphorbia) | X | ||

| Pellaea intermedia Mett. ex Huhn (Creeping cliffbrake) var. pubescens (Mett.) Brown | X | ||

| Ximenesia encelioides Cav. (Golden crownbeard) | X | ||

| Euphorbia strictospora Engelm. (Slimseed euphorbia) | X | ||

| Cissus incisa (Nutt.) Des Moulins (Ivy treebine) | X | ||

| Phanerophlebia umbonata Underw | X | ||

| Phoradendron bolleanum (Seem.) Eichler (Rough mistletoe) | X | ||

| Eriogonum wrightii Torr. (Wright wildbuckwheat) | XX | ||

| Cheilanthes eatoni Baker (Eaton lipfern) | XX | ||

| Perezia nana Gray (Desertholly perezia) | XX | ||

| Aletes acaulis (Torr.) Coult. & Rose (Stemless aletes) | XX | ||

| Lonicera albiflora T. & G. (Bushy honeysuckle) var. dumosa Gray | XX | ||

| Senecio millelobatus Rydb. (Manybract groundsel) | XX | ||

| Artemesia ludoviciana Nutt. (Sagwort) var. albula (Wooten) Shinners | XXX | ||

| Erigeron modestus Gray (Plains fleabane) | XXX | ||

| Galium wrightii Gray (Rothrock bedstraw) var. rothrockii (Gray) Ehrendorfer) | XXX | ||

| Eriogonum hemipterum (T. & G.) Stokes (Wildbuckwheat) | X | XX | |

| Hedyotis fasiculata (Bertol.) Small (Cluster bluet) | XX | ||

| Pellaea microphylla Mett. ex Kuhn. (Littleleaf cliffbrake) | XX | ||

| Ipomopsis aggregata (Pursh) V. Grant (Skyrocket ipomopsis) var. texana (Greene) Shinners | X | ||

| Xanthocephalum lucidum Greene (Sticky snakeweed) | X | ||

| Xanthocephalum microcephalum (DC.) Shinners (Threadleaf snakeweed) | XX | XX | XX |

| Chrysactinia mexicana Gray (Damianita) | XX | XX | XX |

| Melampodium leucanthum T. & G. (Plains blackfoot) | XX | XX | |

| Bommeria hispida (Mett.) Underw. (Hairy bommeria) | XX | X | |

| Eupatorium greggi Gray (Palmleaf eupatorium) | XX | X | |

| Machaeranthera pinnatifida (Hook.) Shinners | X | X | |

| Tribulus terrestris L. (Puncturevine) | X | X | |

| Alternanthera peploides (H. & B.) Urban (Matchaff-flower) | X | X | |

| Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. (Silverleaf nightshade) | X | X | |

| Croton pottsii (Klotzsch.) Muell. Arg. (Leatherweed croton) | X | XX | |

| Euphorbia cinerescens Engelm. (Ashy euphorbia) | XX | ||

| Notholaena sinuata (Lagasca) Kaulf. (Cloakfern) var. integerrima Hook. | XX | ||

| Polygala longa Blake (Narrowleaf milkwort) | XX | ||

| Polygala alba Nutt. (White milkwort) | XX | ||

| Hedyotis polypremoides (Gray) Shinners | XX | ||

| Menodora scabra Gray (Smooth menodora) var. laevis (Woot. & Standl.) Steyermark | XX | ||

| Brickellia veronicaefolia (H.B.K.) Gray (Brickellbush) var.petrophila B. L. Robinson | XX | ||

| Notholaena sinuata (Lagasca) Kaulf. (Bulb cloakfern) var. sinuata | XX | ||

| Polygala scoparioides Chod. (Broom milkwort) | X | ||

| Marrubium vulgare L. (Common horehound) | X | ||

| Croton fruticulosus Engelm. (Bush croton) | X | ||

| Boerhaavia coccinea Mill. (Scarlet spiderling) | X | ||

| Sphaeralcea angustifolia (Cav.) D. Don. (Globemallow) | X | ||

| Porophyllum scoparium Gray (Poreleaf) | X | ||

| Baileya multiradiata Harvey & Gray (Desert baileya) | X | ||

| Senecio longilobus Benth. (Threadleaf groundsel) | X | ||

| Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist (Horseweed) var. glabrata (Engelm. & Gray) Cronquist | X | ||

| Clematis drummondii T. & G. (Texas virgins bower) | X | ||

| Tetraneuris scaposa (DC.) Greene (Plains tetraneuris) var. scaposa | X | ||

| Rivina humilis L. (Bloodberry) | X | ||

| Xanthocephalum sarothrae (Pursh) Shinners (Broom snakeweed) | X | ||

| Notholaena aurea (Poir.) Desv. (Slender cloakfern) | X | ||

| Notholaena standleyi (Star cloakfern) | X | ||

| Teucrium laciniatum Torr | X | ||

| Mirabilis albida (Walt.) Heimerl. (White four-o'clock) var. albida | X | ||

| Amaranthus palmeri Wats. (Palmer amaranthus) | X | ||

| Peganum harmala L. (Harmal peganum) | X | ||

| Hymenoclea monogyna T. & G. (Burrobush) | X | ||

| Salsola kali L. (Russianthistle) var. tenuifolia Tausch | X | ||

| Chamaesaracha coronopus (Denal) Gray (Green false-nightshade) | X | ||

| Berlandiera lyrata Benth. (Greeneye) | X | ||

| Janusia gracilis Gray (Slender janusia) | X | ||

| Selaginella arizonica Maxon (Arizona selaginella) | X | ||

| Dyschoriste linearis (T. & G.) Ktze. (Narrowleaf dyschoriste) | X | ||

| Brickellia californica (T. & G.) Gray (Brickellbush) | X | ||

| Cyphomeris gypsophiloides (Mart. & Gal.) Standl. (Red cyphomeris) | X | ||

| Trixis californica Kellogg (American trixis) | X | ||

Evergreen Woodland Formation

The Evergreen Woodland Formation is a rather distinct formation throughout the southwestern mountains (Gehlbach 1966). The formation is dominated by rather broadly spaced trees up to 25 ft high. Frequently, a space of a crown diameter may occur between individuals where an abundance of grass and/or shrubs develop. Three distinct height layers are evident: trees, shrubs, grasses-herbs. The formation occupies rather mesic slopes with northern exposures at lower elevations (4000-5500 ft) in the Chisos Mountains and on most exposures above 5600 ft.

The dominant trees of this formation in the basin (Table 4) are both evergreen and deciduous in character. The deciduous oak. Quercus gravesii, is the most moisture-dependent of the group and attains great prominence higher in the moist canyons of the Chisos Mountains. A second deciduous oak, Quercus emoryi (Emory oak), is adapted to more xeric conditions at intermediate elevations and is associated with Q. gravesii at the latter's lower limit. An evergreen oak, Q. grisea, is most common on very xeric slopes at elevations below Q. emoryi. Associated with these broadleaf trees are four narrowleaf evergreens: Pinus cembroides, Juniperus deppeana, J. flaccida, and J. pinchoti. The latter is the more xeric or low elevation species, whereas the other three are intermediate to mesic. Prosopis glandulosa (honey mesquite) is the most common introduced tree to invade this formation in the basin. This species is not common at elevations above 5600 ft.

Common shrubs-succulents of the mesic. upper slopes of the formation are Garrya lindheimeri (Lindheimer silktassel), Salvia regla (mountain sage), and Nolina erumpens (foothill nolina). Opuntia engelmannii (Engelmann pricklypear), Agave scabra (Agave), Cercocarpus montanus (true mountainmahogany), and Bouvardia ternifolia (scarlet bouvardia) are intermediate and more widely distributed. At lower elevations Rhus virens (evergreen sumac), Viguiera stenoloba (skeleton goldeneye), Acacia constricta (mescat acacia). and Zexmenia brevifolia (shorthorn zexmenia) are common. Acacia constricta and Opuntia engelmannii are the most common shrub-succulent invaders of the basin. The former is common to ravines in the lower desert region.

The most common grass of the formation is Bouteloua curtipendula (sideoats grama); however, at higher elevations Piptochaetium fimbriatum (pinyon-rice-grass). Muhlenbergia emersleyi (bullgrass), Stipa tenuissima (finestem needle-grass), Stipa eminens (southwestern needlegrass), and Aristida orcuttiana (single threeawn) can be locally dominant. S. tenuissima is the grass most frequently encountered in flats such as Juniper Flat, Stipa Flat, and the flat at the north end of the ridge extending northward from the base of Mt. Emory. At the lower limits of the formation Bouteloua gracilis (blue grama), B. curtipendula, and Muhlenbergia rigida (purple muhly) are common. Invaders of the formation primarily at lower elevations are Bothriochloa barbinodis (cane bluestem), Bouteloua hirsuta (hairy grama), Eragrostis intermedia (plains lovegrass), Aristida glauca (blue threeawn), Setaria macrostachya (plains bristlegrass), and Hilaria mutica (tobosa).

There is a large group of herbs which is found in the formation. The most dominant species are Xanthocephalum microcephalum (threadleaf snakeweed) and Artemesia ludoviciana (Louisiana sagewort), which have become broadly distributed because of intense grazing and disturbance in the formation. A common invader at lower elevations is Chrysactinia mexicana (damianita), an exceedingly odiferous plant. At higher elevations Cheilanthes eatoni (Eaton lipfern), Senecio millelobatus (manybract groundsel), and Galium wrightii (Wright buttonweed) are frequent components of the formation.

As shown in Fig. 3, the Evergreen Woodland Formation is primarily confined to northwest-northeast slopes in the basin. Small stands can develop at the base of sheer cliffs on southern exposures and in canyons, such as the stand in Pulliam Ridge to the north of the campground. In this canyon other highly mesic species are found, such as Phanerophlebia umbonata, Aquilegia longissima (longspur columbine), Acer grandidentatum, and Rhamnus betulaefolia (birchleaf buckthorn). Along small suture lines, talus margins, and small ravines on northern Ward Mountain and Pulliam Ridge, formation representatives are established.

On upper southern exposures within the formation, the vegetation shifts to species which dominate the Chihuahuan Desert Formation. Fouquieria splendens (ocotillo), Dasylirion leiophyllum (smooth sotol), and Agave lecheguilla are common examples. Site 15 exemplifies a low elevation and a southern exposure which can be compared with site 14 on a northern exposure at the same elevation. At a still higher elevation is site 3 on a northern exposure and site 4 on a southern exposure which has shifted to grassland shrub.

The lower margin of this formation in the basin has been the region of most human activity and as a result has lost much of its true woodland character. Sites 8 and 5 demonstrate this best, for in this area the dynamics has been shifted by man to favor the vegetation of the desert formation. An indication of the shift to xeric vegetation is the unusual density which Acacia constricta, Xanthocephalum spp., and Opuntia engelmannii have attained. Evidence that the area should be woodland is the number of isolated large pinyons, junipers, and oaks throughout the area. Accompanying many of these trees are small clumps of the woodland grass Muhlenbergia emersleyi.

Dynamics of the formation throughout its range indicates that all of the trees are reproducing well except in the human-impacted areas. Climatic conditions seem to be adequately supporting their comeback from the drought of the fifties. Unfortunately, the rate of reproduction in the impacted Lower Basin environs do not show this surge (Tables 11 and 18).

Chaparral Formation

The Chaparral Formation is a physiognomically distinct formation, but is quite variable throughout the Southwest. Wells (1965) reports an evergreen chaparral vegetation at higher elevations in the Dead Horse Mountains in the park. The formation is dominated in the basin by rather dense populations of trees and shrubs, seldom exceeding 5 ft in height. Only one height layer is distinct; however, in more sparse areas, grass can be important. The formation appears on two substrates in the basin. The first is the upper talus west slope of Casa Grande. which is igneous in origin, whereas the second area is on limestone at the north east base of Ward Mountain. The formation reaches its greatest development on limestone to the northwest of Laguna Meadow on eastern Ward Mountain.

The dominant trees of the formations are Quercus pungens and Q. intricata (dwarf oak), but small stunted individuals of Q. grisea and Q. emoryi can also be found on the middle slopes of Casa Grande, Quercus intricata is evergreen while Q. pungens is deciduous.

Evergreen shrubs are the primary components of the formation. On the igneous slope the common shrubs are Cercocarpus montanus, Viguiera stenoloba, and Rhus aromatica, while Nolina erumpens and Agave scabra are present as succulents-semisucculents. On the limestone exposure Fraxinus greggi (Gregg ash), Zexmenia brevifolia, and Glossopetalon spinescens (spiny greasebush) are important shrubs. Succulents-semisucculents are of much less importance, but are rep resented by Opuntia engelmannii, Agave scabra, and Dasylirion leiophyllum.

Grasses are locally important in the formation, Bouteloua curtipendula being the most prevalent on both substrates, On the igneous substrate Bouteloua gracilis is of secondary importance, as is Aristida glauca of the limestone substrate. Of the herbs Xanthocephalum spp. are most common, while on the limestone Chrysactinia mexicana is prominent.

Figure 3 shows the Chaparral Formation to be confined primarily to the middle and upper slopes of Casa Grande and to northern exposures of the limestone ridge at the northeast base of Ward Mountain. The formation needs much further investigation into its extent and dynamics. The vegetation has close affinities with the Chihuahuan Desert Formation and on southern exposures shifts to components such as Agave lecheguilla, Dasylirion leiophyllum. and occasionally Larrea tridentata, a species of the Shrub Desert Formation, An example of this is the comparison of site 9 with site 10 (Table 4), Unfortunately, data from other studies are not available to consider the effects of human use; however, Xanthocephalum spp. may be examples of such activity. The Casa Grande slopes are very unstable and may account for its prevalence here; however, grazing has probably created greater instability. Because of the stunted Quercus grisea and Q. emoryi trees, this area may have been woodland, as the northern exposures would suggest.

Chihuahuan Desert Formation

The Chihuahuan Desert Formation is a distinct formation throughout the foot hill region of the Chihuahuan Desert (Gehlbach 1966). The formation is dominated by low-leaf succulents or semisucculents with shrubs and/or grass locally. The two distinct height layers present are those of 1-3 ft for succulents-grasses and 2-5 ft for shrubs. The formation in the basin is limited to very xeric. rocky, southern exposures, although at lower elevations (2-4000 ft) there is little exposure restriction.

The dominant succulents-semisucculents of the formation are Agave lecheguilla, Opuntia engelmannii, and Dasylirion leiophyllum (Table 4). All are leaf succulents except for O. engelmannii which has stem succulence. All are adapted to very xeric conditions, with O. engelmannii being the most broadly distributed and the most common invader of the mesic upland.

The shrubs most common in the formation are Rhus virens (evergreen sumac), Acacia constricta, Viguiera stenoloba, Fraxinus greggi, and Zexmenia brevifolia Found in localized areas are Glossopetalon spinescens. Dalea frutescens (black dalea), Mimosa biuncifera (catclaw mimosa). Aloysia wrightii (Wright aloysia), and A. lycioides (whitebrush) In areas which are highly disturbed or eroded, Larrea tridentata is present. Along the ravines in this formation, shrubs such as Eysenhardtia texana (Texas kidneywood), Vauquelina angustifolia (slimleaf vanquelina), Anisacanthus insignis (dwarf anisacanth) and Aloysia lycioides are common. Most of the shrubs are microphyllus and deciduous.

The grasses which are restricted primarily to the Chihuahuan Desert Formation are Heteropogon contortus (tanglehead), Bouteloua breviseta (chino grama), B. eriopoda (black grama), Schizachyrium scoparium (bluestem), and Muhlenbergia porteri (bush muhly) Several grasses common to the formation which are also found throughout the mountains are Bouteloua curtipendula, Bothriochloa barbinodis, Bouteloua gracilis, Aristida glauca Muhlenbergia emersleyi and Lycurus phleoides (wolftail) Bouteloua breviseta, the most dominant species at lower elevations in the park, is an unimportant species in the basin. Bouteloua curtipendula, Heteropogon contortus, Panicum obtusum (vine mesquite), and Sporobolus cryptandrus (sand dropseed) are common invaders into disturbed areas of the formation.

A large group of herbs is found in the formation. Tables 4 and 6 present many of those encountered in the study. It is of interest that most herbs are of little importance in the formation. Many of them, with the exception of Xanthocephalum spp., Chrysactinia mexicana, and Melampodium leucanthum (plains blackfoot), are relatively small in size. The first two are common invaders following heavy grazing and are not consumed by livestock.

Because the formation is confined to southern exposures (Fig. 3), it is relatively restricted to Pulliam Ridge, Vernon Bailey, and southern slopes below the Upper Chisos Basin. Small isolated areas develop within the other two formations on extremely xeric exposures. An example of the shift on opposing slopes is shown by site 12, a northern exposure, and by site 13, a southern exposure, both at low elevations north of Ward Mountain. The northern exposure is very similar to chaparral, except that few evergreen shrubs and oaks are present. A study of the relationship between the two formations should be undertaken in the Chisos Mountains.

The dynamics of this formation has been investigated (Whitson 1970) in con junction with the Shrub Desert Formation at lower elevations throughout the park. Based upon low elevation trends, the Chihuahuan Desert Formation probably expanded greatly in the basin during grazing pressure and the following drought. Although Agave lecheguilla cannot compete with dense grass cover, it can invade when the cover is reduced.

Additional data to support the expansion are a series of new photographs by Warnock (1967). A site along the base of Pulliam Ridge, originally photographed in 1935 and duplicated in 1966, exhibited an increase in Opuntia engelmannii and grasses such as Heteropogon contortus and Bouteloua eriopoda. Quercus grisea decreased noticeably. A second site, a view of Mt. Emory from the base of Pulliam Ridge, indicated an increase in O. engelmannii, Acacia constricta, Rhus virens, R. aromatica, and Juniperus pinchoti. The new photographs did not specifically demonstrate Agave lecheguilla; however, the increase in O. engelmannii and Acacia constricta would indicate formation expansion. The higher importance of grasses at all sites sampled, with the exception of one site, tends to substantiate the fact that no appreciable expansion is presently occurring. Small Agave lecheguilla individuals were not common at the sampled sites. Determination of the long-range trend must await future investigations. Concern and observation must be given to the advancement of the formation, since a lengthy span of time is required before woodland vegetation can reinvade an area controlled by the desert vegetation.

Summary and comparison

The three vegetation types are distinctive in physiognomy due to the different strata that predominate in each. Accentuating the strata are the different life-forms of the dominant species. In the Evergreen Woodland Formation, oak, pin yon, and juniper trees dominate, with shrubs and grasses being subordinate; while in the Chaparral and Chihuahuan Desert Formation, shrubs and grasses dominate the physiognomy of the vegetation. Both formations have low-growing life-forms, but differ significantly in their leaf-form. The desert vegetation exhibits leaf succulence with a reduction in stems, except Opuntia engelmannii with a succulent stem and reduced, ephemeral leaves, while the Chaparral vegetation has extensive stem systems and nonsucculent leaves. The leaves of this vegetation type are frequently broad evergreen or microphyllus.

The importance of these characteristics is allied with their origin and evolution with respect to climate. The woodland vegetation has many counterparts which developed in the northern temperate, mesic highlands from Arcto-Tertiary Geoflora, while the chaparral and desert vegetation have counterparts in the Madro-Tertiary Geoflora (Axelrod 1950, 1958, 1959). This flora developed in the southern temperate lowlands under arid conditions. These diverse origins, along with the prevailing climate in the basin toward aridity, favor those species with high physiological tolerance for low moisture, This is extremely evident in vegetation dynamics since many more desert vegetation species are found in the Evergreen Woodland and Chaparral Formations, while few of their species are found in the Chihuahuan Desert Formation.

Other examples of these factors are evident when comparing formations with respect to individual densities and vegetation cover. An average of 273 individuals occurred in the Chihuahuan Desert Formation transects, whereas 129 and 193 occurred, respectively, in the Chaparral and Evergreen Woodland Formations. The average percentage of cover for all transects in each formation, in the order presented above, was 50(43-62), 68(63-71), and 79(51-110) percent. This demonstrates that there are many small individuals comprising the desert vegetation, while in the woodland, where stratification is important, there are fewer large individuals. Chaparral vegetation was intermediate with respect to these values.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap5.htm

Last Updated: 1-Apr-2005