|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Mountain Goats in Olympic National Park: Biology and Management of an Introduced Species |

|

APPENDIX B:

Review of the Historical Evidence Relating to Mountain Goats in the Olympic Mountains Before 1925

S. Schultz

The generally accepted perception that mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) were not part of the historic fauna of the Olympic Mountains has recently been challenged (Lyman 1988; Anunsen 1993). These challenges have been based in part on a conjectured reconstruction of mountain goat distribution in the Pacific Northwest during the late Quaternary and the speculation that goats in remote areas of the Olympic Mountains may have gone unreported during early surveys. The latter notion is reinforced by historical accounts of widespread use of mountain goat wool among the native people living along the Strait of Juan de Fuca and a few early passing references to the presence of goats in the Olympic Range.

These concerns led the National Park Service to reexamine information concerning the past occurrence of mountain goats on the Olympic Peninsula. Schalk (1993) evaluated ethnographic and archeological evidence relative to the prehistoric occurrence of goats. My review examines early accounts of explorations on the Olympic Peninsula, paying special attention to wildlife observations and statements concerning the presence or absence of mountain goats before their 1925 introduction. Historic references to native use of mountain goat wool on the Olympic Peninsula and in the surrounding area also are considered. A variety of sources was consulted, including published and unpublished expedition narratives, journals, field notes, and correspondence; early newspaper accounts; U.S. Geological and Biological Survey published reports and unpublished field records; catalogues of mammals; territorial governors' reports; U.S. Forest Service files; and selected nineteenth- and early twentiethth-century literature on natural history, recreation, and game hunting. Manuscript collections at the Smithsonian Institution, the Library of Congress, the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley, and other reference libraries were searched for relevant material. A complete bibliography containing references searched but not cited here is contained in a draft of this report (Schultz 1993).

The review of information about the possible historic occurrence of mountain goats in the Olympic Mountains involves the problem of interpreting negative evidence (Lyman 1988). If mountain goats were indeed not present, no reported sightings of them should be expected. However, a failure to find reported evidence of mountain goats in the historic record cannot alone be used to argue that mountain goats were not present: a failure to report is not proof of absence. In fact, there are a few historic accounts that assert that mountain goats were present in the Olympics. Therefore, as many pre-1925 accounts of wildlife observations as could be located, whether or not they mentioned goats, were examined. The following pages review these accounts and attempt to evaluate their completeness, the author's opportunity for firsthand observation or his reliance on credible informants, and the likelihood that mountain goats would have been reported if they had been observed. Sufficient narrative and interpretive detail are provided to clarify the context (and limits) of each account. The discussion attempts to assess the reliability of the various reports. The overall effort has been to provide a thorough, careful, and balanced consideration of all located records that pertain to the issue.

Maritime Explorers

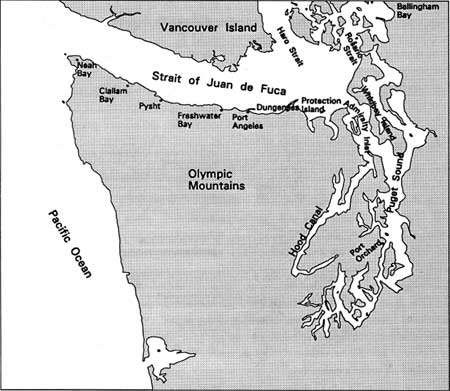

Spanish Coastal Exploration, 1790-1792

The discovery of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the waterway between the southern shore of Vancouver Island and the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula, has been attributed to a Greek mariner who sailed for Spain under the name of de Fuca in 1592. Although the western entrance and perhaps other portions of the strait were visited by English, Spanish, and American navigators during the late 1780's, Spanish explorers were the first to chart the entire length of the strait in 1790 (Fig. B1). In that year, Spanish naval lieutenant Francisco Eliza dispatched Manuel Quimper in one ship, Princesa Real, from the port of Nootka on the west coast of Vancouver Island to explore the interior of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. During June and July, Quimper charted both the north and south coasts of the strait as far inland as the San Juan Islands. From an anchorage at Dungeness, on the northern coast of the Olympic Peninsula, his party explored the eastern end of the strait, discovering the entrances to Haro and Rosario straits to the north, Port Discovery (later so named by Vancouver) and Protection Island, and the opening of Admiralty Inlet. Quimper noted that the Indians at Dungeness wove woolen cloaks, but he did not describe the wool (Wagner 1933:131). On his return, Quimper visited points along the north coast of the strait, Freshwater Bay on the Olympic Peninsula, and Neah Bay, which he named Núñez Gaona when he took possession of it on 1 August. There he observed "sea otters, bears, deer, rabbits, foxes and dogs" (Wagner 1933:127).

|

| Fig. B1. Spanish anchorages and landings (1790-1792) and areas visited by Vancouver in 1792. |

In a general description of the terrain and wildlife found along the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Quimper states

The mountains on the north side are suggestive of some fertility, and of being traversed along their summits. On their slopes, land which seems suitable for crops was noted, from which various small streams run down and empty into the strait. Those on the south side are exactly like those on the north side except for their height. As this is very great their summits are covered with snow. I therefore do not think they can be traversed. On some, high pines and other trees can be seen. Buffalo, stags, deer, wild goats, bears, leopards, foxes, hares, and rabbits feed on their luxuriant pastures, and uncommonly large partridges, quail and other unknown kinds of little birds on their seeds (Wagner 1933:128).

Wagner indicates that the word "cibolos," translated as "buffalo," was the term used in the early Spanish reports for elk, an animal with which the Spaniards were unfamiliar (Wagner 1933:162). Wagner does not indicate what term was translated as "wild goats." However, it is highly unlikely that the Spanish explorers could have seen mountain goats from shipboard or from their anchorage near lowlands at Dungeness. They made no explorations of the interior other than to locate water and to hunt for food in areas close to the coast. There is no record of specific observations of wildlife made on specific dates in the available translated narratives. Quimper's statement, therefore, is an unsupported generalization.

The following year Eliza was instructed to carry out further explorations in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. On 26 May 1791, he entered the strait with two ships, the San Carlos and the schooner Santa Saturnina. After a month spent exploring among the San Juan Islands and in the Strait of Georgia, they crossed the strait to Dungeness on 28 June, and the next day moved to Port Discovery. On 1 July the schooner and a longboat under the command of Jose María Narváez left Port Discovery to explore the coastline to the east and as far north as the vicinity of Texada Island. Narváez saw a number of whales in the Gulf of Georgia and speculated that it must have another entrance in addition to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, where they had only noted three or four whales. The San Carlos remained in Discovery Bay for 25 days.

According to Henry Wagner, historian of these expeditions, "Eliza does not enter into any detailed description of the animals, birds and fish found in the strait because as he said, Quimper had described them the year before" (Wagner 1933:34). However, Eliza did give a detailed description of an elk that was shot at Discovery Bay:

A great abundance of deer is found in these places, among which are some larger than any horse and having more flesh than any steer... The shape of the body, feet and legs is like those of a very large horse. The hoof is like that of a bull, the ear like that of a mule and the horns like those of a deer, except that they are extremely large and thick, each being one yard and two inches long with six points or little horns each ten to thirteen inches long. All the animals are also found which occur in the description of the Estrecho de Fuca by Don Manuel Quimper (Wagner 1933:151).

The pilot of Eliza's ship, Juan Pantoja y Arriaga, provided some additional information on the elk and the use of wool blankets by the Indians of that area. Pantoja does not elaborate whether the blankets were made of goat wool or wool made from the hair of dogs. Both types were in use among Olympic Peninsula tribes (Schalk 1993).

The horns are entirely covered with a skin of down, not very thick but very close-grained, so fine that when we touched it we seemed to be passing our hands over velvet. What he has on his body however is just the reverse as it is the same as that on a deer. The color of the head is between black and brown and that of the horns between ash color and dark pearl color. When they were dressing it there were some Indians present who explained very clearly that it was of the skin of this animal that they made their beautiful and perfectly dressed leather shirts, which ordinarily all possess. We bought some of these which look like the breast doublets in Spain but are very thick. On asking them if they made use of these to protect themselves from intemperate weather they said "no", but that for that purpose they had and wear an abundance of blankets of very coarse wool, with which most of the crew have supplied themselves, and that they only used these skins during their skirmishes or war to protect themselves from the arrows (Wagner 1933:179).

Pantoja also noted that other animals observed at Discovery Bay were "bears, leopards, coyotes, wolves, deer, hares and rabbits and two kinds of doves and chickens" (Wagner 1933:188). Wagner noted the "leopards" were probably cougars. The mention of coyotes is interesting because they are not thought to have taken up residence on the Olympic Peninsula until early in the twentieth century, after the wolf had been practically eliminated and logging had opened up some of the heavily timbered areas. Reagan's report of them (1909a) seems to be the first (Scheffer 1949:58). Pantoja's list of animals found along the Strait of Juan de Fuca is a generalization very similar to the statement made by Quimper.

On both coasts, particularly on the shores, different kinds of pasture are very common on which feed buffalo, stags, deer, wild goats, hares and rabbits. On the seeds and abundant fruits, some of which are agreeable to the palate, two kinds of doves feed, one of the color and shape of our domestic pigeon, different unknown little birds and a kind of the color and shape of a chicken, with golden feathers and a swift flight like that of the partridge (Wagner 1933:184).

Current common names of mammals and birds Quimper and Pantoja may have observed include cougar, bobcat, wolf, black bear, elk, black-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, ruffed and blue grouse (Bonasa umbellus, Dendragapus obscurus), band-tailed pigeon (Columba fasciata), and mourning dove (Zenaida macroura).

Spain launched one final exploring expedition into the Strait of Juan de Fuca in June 1792. Two schooners, Sutil and Mexicana, commanded by Dionisio Alcala Galiano and Cayetano Valdés, sailed from Nootka and arrived at Neah Bay on 6 June. After leaving Neah Bay on 8 June, the expedition had no further contact with the Olympic Peninsula. However, the account of this expedition is interesting for its observations of the use of wool among various Native American tribes encountered along the coastlines of Vancouver Island and the British Columbia mainland. On the schooners' arrival at Esquimalt Harbor on the southeast end of Vancouver Island, they were met by Indians in canoes.

When we came near Eliza anchorage, three canoes, with four or five Indians in each, approached the Mexicana....The natives were dressed in cloaks of wool, and they brought other new sheep skins which they were prepared to exchange for a piece of copper (Jane 1802:34).

It is not clear whether the wool was obtained from the same animal as the "sheepskins" or from dogs or whether the "sheepskins" may have been goat hides, dogskins, or, in fact, sheepskins. On another occasion, near Guemes Island, the account mentions trading for "a dogskin cloak decorated with feathers and a tanned skin" (Jane 1802:40). Further up the east coast of Vancouver Island, near Nanaimo, the ships were approached by 39 canoes carrying Indians who were wearing and trading wool cloaks.

They also offered new cloaks, which we afterwards gathered were made of dog's hair, both because we could discover no difference in their texture from that of dog's hair and because in their settlements there were a large number of these animals, most of which had been shorn. They are of moderate size, apparently similar to English-bred dogs, very long-haired and generally white; among other characteristics which distinguish them from those of Europe is their manner of barking, which is no more than a miserable yelping (Jane 1802:48).

While exploring a large inlet of the continental coast along the Strait of Georgia, Valdés noticed a carved wooden plank depicting a standing human figure surrounded by five horned animals which appeared to be goats. Valdes named the inlet "Tabla Inlet" for the carved plank. Today called Toba Inlet, it is located in an area of the British Columbia coast where mountain goats are present in the Coast Range. Engstrand (1981) reproduces Cardero's drawing with the label "Tablet found on the east end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca," whereas Tabla or Toba Inlet is well north of what is presently regarded as the Strait of Juan de Fuca. This caption reflects some haziness in the definition of the strait's boundaries at the time of Spanish exploration, the first expeditions to chart these waterways. The Strait of Juan de Fuca was at first regarded by the Spanish explorers as one continuous passage extending through the waterways to the north of its present eastern end. This perception is illustrated by the summary statement regarding the 1792 expedition.

We arrived at Nootka four months after we had set out from that harbor. . . .When it had once been settled, as it was as a result of this exploration, that there was no passage to the Atlantic through the Fuca Strait, the gloomy and sterile districts in the interior of this strait offered no attraction to the trader, since in them there were no products, either of sea or land, for the examination or acquisition of which it was worth while to risk the consequences of a lengthy navigation through narrow channels, full of shoals and shallows (Jane 1802:89).

The subtitle of the account of the exploration—"the narrative of the voyage made in the year 1792 by the schooners Sutil and Mexicana to explore the Strait of Juan de Fuca"—also supports a broader view of the perceived boundaries of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The explorations took place in the inland passage between Vancouver Island and the mainland. Hence, if the Spanish narratives of these explorations refer to the presence of wild goats along the Strait of Juan de Fuca, one possible explanation is that they encompassed that part of the British Columbia mainland where mountain goats are native.

Captain George Vancouver, 1792

The Spanish captains Galiano and Valdés encountered Vancouver's ships Discovery and Chatham on the night of 12 June in Birch Bay, and for about a month they pursued a joint exploration of the British Columbia coastline and islands. Vancouver had entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca on 29 April and had explored the Puget Sound area before heading north along the continental coast (Fig. B1). Like Eliza the year before, Vancouver also anchored in Discovery Bay and from there spent about 2 weeks exploring the length of Hood Canal with small boats. Regarding the fauna of the area, Vancouver observed that "The only living quadrupeds we saw, were a black bear, two or three wild dogs, about as many rabbits, several small brown squirrels, rats, mice, and the skunk, whose effluvia were the most intolerable and offensive I ever experienced." Among the birds Vancouver noted were "tern, the common gull, sea pigeon of Newfoundland [pigeon guillemot], curlews, sandlarks [sandpiper], shags [cormorant], and the black sea pye [oystercatcher], like those in New Holland and New Zealand."

Nor did the woods appear to be much resorted to by the feathered race; two or three spruce partridges had been seen; with few in point of number, and little variety of small birds: amongst which the humming birds bore a great proportion. At the outskirts of the woods, and about the water side, the white headed and brown eagle; ravens, carrion crows, American king's fisher, and a very handsome woodpecker, were seen in numbers; and in addition to these on the low projecting points, and open places in the woods, we frequently saw a bird with which we were wholly unacquainted, though we considered it to be a species of the crane or heron; some of their eggs were found of a bluish cast, considerably larger than that of a turkey, and were well tasted. These birds have remarkably long legs and necks, and their bodies seemed to equal in size the largest turkey. Their plumage is uniformly of a light brown, and when erect, their height, on a moderate computation, could not be less than four feet. They seemed to prefer open situations, and used no endeavors to hide or screen themselves from our sight, but were too vigilant to allow our sportsmen taking them by surprise. Some blue, and some nearly white herons of the common size were also seen (Meany 1907:119-120).

Vancouver's naturalist, Archibald Menzies, mentioned a couple of encounters with skunks, "a species of Diver" (probably a pigeon guillemot [Cepphus columba]) that burrowed into the sandy cliffs, black oystercatchers (Haematopus bachmani), and rhinoceros auklets (Cerorhinca monocerata). At Port Ludlow, Menzies observed that the Indians' clothing consisted of deer, lynx (probably bobcat), marten (Martes americana), and bear skins, and that one Indian "had a very large skin of the brown Tyger Felis concolor which was some proof of that Animal being found thus far to the Northward on this side of the Continent, but we saw very little of the Sea Otter Skins among them, which also shows that Animal is not fond of penetrating far inland" (Newcombe 1923:26-27). While in Puget Sound, he mentions trading for the skins of bear, lynx, raccoon, rabbit, and deer. Southeast of Port Townsend Menzies saw "a white animal. . .which we supposed to be a Dog about the size of a large Fox but it made off so quick into the woods that those who saw it were not certain what it was" (Newcombe 1923:25). This was probably a feral wool dog. On 31 May, off the coast near Everett he reported that "Some dogs had been left on shore on this Island whose yellings were heard several times in the night," but apparently he did not get a look at these dogs (Newcombe 1923:44). These were also probably wool dogs, which were sometimes kept on islands to prevent interbreeding with other village dogs (Shalk 1993).

Vancouver described wool dogs he observed near Port Orchard on Puget Sound:

The dogs belonging to this tribe of Indians were numerous, and much resembled those of Pomerania, though in general somewhat larger. They were all shorn as close to the skin as sheep are in England; and so compact were their fleeces, that large portions could be lifted up by a corner without causing any separation. They were composed of a mixture of a coarse kind of wool, with very fine long hair, capable of being spun into yarn. This gave me reason to believe that their woollen clothing might in part be composed of this material mixed with a finer kind of wool from some other animal, as their garments were all too fine to be manufactured from the coarse coating of the dog alone. The abundance of these garments amongst the few people we met with, indicates the animal from whence the raw material is procured, to be very common in this neighborhood; but as they have no one domesticated excepting the dog, their supply of wool for their clothing can only be obtained by hunting the wild creature that produces it; of which we could not obtain the least information (Meany 1907:136).

Haeberlin and Gunther (1930) have stated that Indians of the Puget Sound region wove blankets of dog hair, mountain goat wool, and also a combination of feathers and fireweed fibers. The mountain goat wool was obtained from the Skykomish tribe to the northeast of Puget Sound where goats are found in the Cascade Range.

Further north along the Strait of Georgia, the explorers observed women weaving woollen blankets.

In one place we saw them at work on a kind of coarse Blanket made of double twisted woollen Yarn & curiously wove by their fingers with great patience & ingenuity into various figures thick Cloth that would baffle the powers of more civilized Artists with all their implements to imitate, but from what Animal they procure the wool for making these Blankets I am at present uncertain; it is very fine & of a snowy whiteness, some conjectured that it might be from the dogs of which the Natives kept a great number & no other use was observed to be made of them than merely as domesticated Animals. Very few of them were of a White colour & none that we saw were covered with such fine wool, so that this conjecture tho plausibly held forth appeared without any foundation (Newcombe 1923:58).

The editor of Menzies' journal, C. F. Newcombe, notes that the following year, in June 1793, Vancouver and Menzies saw skins of the animal "from which the fine white wool comes" at a village near Bella Bella, on the British Columbia mainland coast, just north of Vancouver Island.

It had small straight horns and was therefore supposed to be an unknown goat. The animal at this time was said to be high up in the mountains, but used to come down in winter. Menzies adds that at Nootka and Whannoh (i.e., the Nimpkish village) the natives were ignorant as to the animal "which they procured by barter from the natives inland." (Menzies' Journal, under date June 16th, 1793.) It was probably from this locality that Vancouver procured the mutilated skin which Richardson refers to under "Mountain-goat, Capra americana," in his Fauna Boreali-Americana, p. 268 (Newcombe 1923:154).

José Mariano Moziño, a Spanish naturalist stationed at Nootka, on Vancouver Island in 1792, also noted the use of mountain goat wool among the Indians who lived there, although mountain goats were not found on the island.

Their dress is very simple. It commonly consists of a square cape woven from beaten cedar fibers and the wool of some quadruped, which I suspect to be a bison or mountain goat. They are provided with these by trade with the Nuchimanes, who perhaps have some commerce with the tribes of the continent where these beasts are found in abundance (Moziño 1970:13).

I. H. Wilson, translator and editor of Moziño's account, identifies the Nuchimanes as Nimpkish Kwakiutl who occupied a portion of the east coast of Vancouver Island as well as the mainland across from it.

United States Exploring Expedition, 1841

In 1838, the United States sent out six ships under the command of Lieutenant Charles Wilkes on an expedition to collect data and specimens in support of navigation, commerce, diplomacy, and science. During 1838-42, the expedition explored the coasts of South America, the Pacific Northwest, the South Seas, 1,500 miles of the Antarctic coastline, and other points of scientific interest. Titian Ramsay Peale, one of the expedition's naturalists, collected most of the mammal and bird specimens. John Cassin of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia prepared the final report on the birds and mammals (Cassin 1858). The expedition explored the Puget Sound region during summer 1841. Wilkes's narrative of this exploration makes very little mention of wildlife. He reported that although the officers made several excursions into the woods at Port Discovery, no large game was seen, only "crows, robins, &c." and land snails (Wilkes 1845, 4:302). In the vicinity of Port Orchard, Wilkes commented that "The woods seemed alive with squirrels, while tracks on the shore and through the forest showed that the larger class of animals also were in the habit of frequenting them" (Wilkes 1845, 4:47 9).

Regarding the use of wool among the Native Americans of the area, Wilkes remarked that near Port Gardner (Everett), "The dress of the Sachet [Skagit?] does not vary much from that of the other tribes, and generally consists of a single blanket, fastened with a wooden pin around the neck and shoulders. Those who are not able to purchase blankets wear leather hunting-shirts, fringed in part with beads or shells, and very few are seen with leggings" (Wilkes 1845, 4:481). Apparently by this time, blankets were more often purchased than manufactured. However, at Neah Bay he noted the use of native blankets.

Their dress consists of a native blanket, made of dog's hair interspersed with feathers: this is much more highly valued than the bought ones, but is rarely to be obtained (Wilkes 1845, 4:488).

Wilkes's narrative and the report on the mammal specimens collected by the expedition made no mention of mountain goats from the Puget Sound region.

Suckley, Cooper, and Gibbs (Pacific Railroad Surveys), 1853-1856

In 1853, Congress authorized a survey to locate a transcontinental railway route. Isaac Stevens, Governor of Washington Territory, led the expedition to explore a northern route between the 47th and 49th parallels. Dr. George Suckley and Dr. James Cooper served as surgeons and naturalists to parties of the expedition. George Gibbs was geologist and botanist for the party that included Cooper during its survey of the Cascades. These three naturalists did additional collecting in Washington state in areas of western Washington that were not on the original survey routes. Gibbs and Suckley collected in the Puget Sound region, including some locations on the Olympic Peninsula. In reporting on the mammals collected on the survey, Gibbs stated that mountain goats were common to both the Cascades and the Rocky Mountains. "The Yakimas and Snolqualme [sic] Indians get them in the Cascade Mountains, north of the Columbia, in latitude 47° 30'. They were formerly, if not now, abundant on Mount Hood" (Suckley and Gibbs 1860: 137). Suckley added that he

obtained several hunters' skins of the mountain goat from the localities north of the Columbia River.... Mr. Craig, an old Indian trader.. says that these animals are quite abundant in the mountains near the Kooskooskia and Salmon rivers, streams which empty into Snake river, and that in the country of the Nez Perces. . .they are found in great numbers on the bald hills and bare mountains of that locality, and that upon these they can be seen from a great distance feeding In "large droves" (Suckley and Gibbs 1860:137).

Suckley also mentioned mountain goats having been collected in the Cascade Mountains north of Mount Rainier and from the upper Nisqually. He recounted having seen "dozens" of mountain goat skins in Indian lodges on Whidbey Island, northeast of the Olympic Peninsula, and stated that these skins were "obtained from the Indians living about Mount Baker, in the Cascade Range" (Suckley and Gibbs 1860:137). These reports do not include the Olympic Mountains in the range of mountain goats. Suckley, who lived in western Washington for 4 years, would probably have mentioned the presence of mountain goats in the Olympics if he had evidence or had heard reports of their being there.

Nineteenth-century Ethnographic Accounts

A number of nineteenth-century accounts of the lifestyle of Native Americans on the Olympic Peninsula mention the use of both mountain goat and dog wool. John Dunn, a Hudson's Bay Company employee, reported that the Clatset [Makah] Indians of Cape Flattery "manufacture some of their blankets from the wool of the wild goat" (Dunn 1845:157). Both Lieutenant Wilkes (1845) and George Gibbs (1877) in relating visits to Neah Bay at about the same time that Dunn wrote, reported that the Makah used dog wool in weaving their blankets. In addition to his survey of northwest mammals, Gibbs prepared a report on the Indian tribes of western Washington and northwestern Oregon, written in 1855 or 1856 but published posthumously in 1877 (Gibbs 1877). Gibbs reported that an 1850 visitor to Neah Bay had observed women weaving dog's hair blankets and that "the Indians of the Sound and the Straits of Fuca attained considerable skill in manufacturing a species of blanket from a mixture of the wool of the mountain-sheep and the hair of a particular kind of dog" (Gibbs 1877:174,219). He described wool dogs as "of pretty good size, and generally white, with much longer and softer hair than either [the hunting dogs or the women's pets], but having the same sharp muzzle and curling tail as the hunting-dog" (Gibbs 1877:221). Gibbs also noted that "There are mountain-sheep or, more properly goats, in the higher parts of the [Cascade] range," hunted for their wool, which was "an article of trade" (Gibbs 1877:193, 220). He described far-ranging trade patterns extending across the Cascade Mountains for procuring wool and other commodities.

The western Indians sold slaves, haikwa, kamas, dried clams, &c., and received in return mountain-sheep's wool, porcupine quills, the grass from which they manufacture thread, and even dried salmon, the product of the Yakama [sic] fisheries being preferred to that of the sound (Gibbs 1877:170; As is apparent from Gibbs' statement on page 193, cited above, Gibbs used "mountain-sheep" and "mountain-goats" interchangeably.1 See Schalk [1993], for a further discussion of trade.).

1Anthropologist Dr. B. Lane suggests that Gibbs's confusing reference to "mountain-sheep or, more properly goats" may have resulted from an early (1855)—and later corrected—misidentification of the Nisqually word for mountain goat (s'weht-leh) with mountain sheep, which were also found in the Cascade Range (B. Lane, Victoria, British Columbia, personal communication. 1993).

Charles Pickering, anthropologist with the Wilkes Expedition, stated that the Chinook Indians, among whom he included all natives inhabiting the southern shore of the Straits, "weave blankets and belts, principally from the wool of the Mountain Goat (Capra Americana, an animal said to be abundant to the northward)" (Pickering 1895:17; emphasis added).

Hubert Howe Bancroft (1875) cites an additional reference to wool blankets on the Olympic Peninsula:

The Queniults [Quinaults] showed "a blanket manufactured from the wool of mountain sheep, which are to be found on the precipitous slopes of the Olympian Mountains" (Bancroft 1875:215-216, note 100).

The source of Bancroft's assertion is given as Alta California, 9 February 1861, quoted in California Farmer, 25 July 1862. (The original statement has not been located.) Ronald Olson, writing in 1936, based on interviews in 1925-27 with Quinault elders whose personal observations extended back to the mid-nineteenth century, stated that "the mountain goat and mountain sheep were unknown" to the Quinault Indians (Olson 1936:15; Schalk 1993:7-9).

Interior Exploration

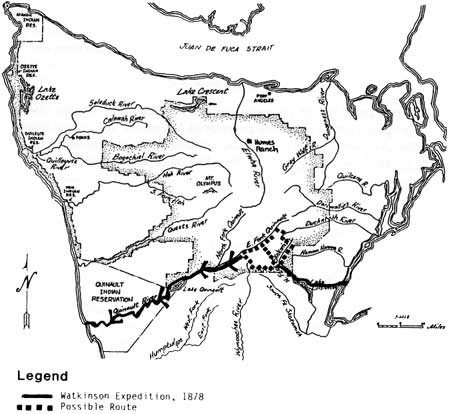

Watkinson 's Exploration, 1878

An account of an expedition that crossed the Olympic Peninsula in 1878 was sent by Eldridge Morse of Snohomish City to historian Hubert Howe Bancroft (Morse 1880). In September of that year, five young loggers led by Melbourne Watkinson hiked from Hood Canal to Lake Quinault and back again, taking 18 days for the round trip (Fig. B2). Morse's account was based on Watkinson's diary and additional information supplied to Morse by Watkinson. The adventurers traveled from Lake Cushman up the North Fork of the Skokomish River into high country, where they reported climbing a "steep mountain...about as high as Mount Olympus" and crossing over a divide into a river valley, presumably the East Fork of the Quinault. They reported shooting 1 elk and seeing others, including a band of 16, shooting 2 deer, seeing additional signs of elk and bear, and hearing wolves at night. Although the men traversed appropriate terrain, Watkinson did not mention mountain goats.

|

| Fig. B2. Route of interior exploration by the Watkinson Expedition of 1878. From Evans (1983). |

Governors' Reports, 1884 and 1888

Governors of Washington Territory submitted yearly reports on population, economic activity, agricultural production, resources, institutions, and various other territorial affairs to the Secretary of the Interior. The report of Governor Watson C. Squire in 1884 was notable for its listing of Washington's mammals and birds (Squire 1885). Among the 41 mammals mentioned was the mountain goat. Its range within the territory was not specified. Governor Eugene Semple included more information on some of the territory's larger game animals in a section titled "Information for Sportsmen" in his 1888 report.

A species of mountain goat, which very nearly answers the description of the ibex, is found near the snowy peaks between the lines of perpetual ice and timber. This is their habitat; they were not driven there by their enemies. They are gregarious, and, therefore, may be readily noticed in the distance, but they are difficult to approach. These animals exist in considerable numbers on the sides of Mounts Ranier [sic], St. Helens, and Baker, in the Cascade Range, and, possibly, may be found in other similar altitudes (Semple 1889:923).

Semple also included in his report a section on the Olympic Mountains, commenting that "it is a land of mystery. . .the interior is incognita" (Semple 1889:925-926). The Olympic Mountains had served as hunting grounds for peninsula tribes for several thousand years, and there had undoubtedly been occasional forays into the mountains by local homesteaders, hunters, trappers, and loggers since settlers began to reside on the peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century. But the resources of the peninsula's interior had remained essentially unreported and a subject of conjecture. Semple's romantic description of the interior's mystery inspired popular interest in exploration of the Olympics.

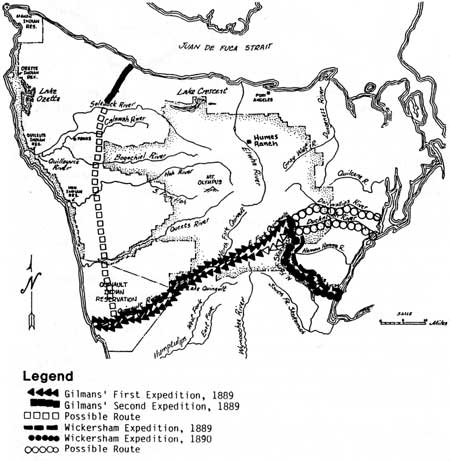

Gilman's Explorations, 1889-1890

An early venture into the Olympics was made in October-November 1889 by C. A. Gilman, a former lieutenant governor of Minnesota, and his son Samuel C. Gilman, a civil engineer (Fig. B3). The Gilmans left the Quinault Indian agency on the Pacific Coast on 20 October, traveled by canoe across Lake Quinault, and continued upriver, reaching the forks of the Quinault on 25 October. They followed the East Fork by canoe until they encountered a logjam, and then continued eastward on foot to within 2 miles of the foot of a mountain they identified as Mount Constance (but probably Mount Anderson). They reported climbing several peaks in the southeastern Olympics, but their exact itinerary wasn't detailed. In an account given later to a Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter, they mentioned each of them shooting an elk and seeing many others, and their Indian guide killing four, but made no other wildlife observations. They returned to Grays Harbor on 27 November (Gilman 1890). A month later, the Gilmans again explored the west side of the Olympic Peninsula from the mouth of the Pysht River on the Strait of Juan de Fuca south to the Quinault River. They did not travel into the mountains on this second trip. In a brief report on the Olympic Peninsula based on these two excursions, Samuel Gilman's only mention of wildlife stated that "the streams teem with splendid fish and game is abundant" (Gilman 1890).

|

| Fig. B3. Routes of interior exploration by both the Gilman and Wickersham expeditions of 1889 and 1890. From Evans (1983). |

A more lengthy article about the Olympic Peninsula by Samuel Gilman was published in National Geographic in 1896. An editor's note at the beginning of this article states, "The following valuable article is based largely on the explorations of the writer in the comparatively unknown region he describes. A melancholy interest attaches to it, Mr. Gilman having been suddenly cut off, at the early age of thirty-six and in the midst of an increasingly useful and promising career, only a few days after the transmission of the article for publication and before he could be made aware of its acceptance" (Gilman 1896:133). This leaves open the possibility that the article may have been edited and altered, and that Gilman would not have been able to correct any inaccuracies. An inquiry to National Geographic's Research Division failed to turn up the original manuscript or any other material relating to it. Gilman's posthumous article states

Game is plentiful, and it would be a paradise for the hunter were it not so difficult of access. In addition to elk and bear, before mentioned, are deer, mountain goat, cougar, beaver, otter, fisher, wildcat, marmot, geese, ducks, grouse, partridge, quail, pelican, and many smaller or less desirable birds and animals (Gilman 1896:138).

Gilman does not state here that he personally observed mountain goats in the Olympics. This generalized summary of wildlife also includes "partridge," which are not found on the peninsula, although there are two species of grouse, and "quail," which is an introduced species.

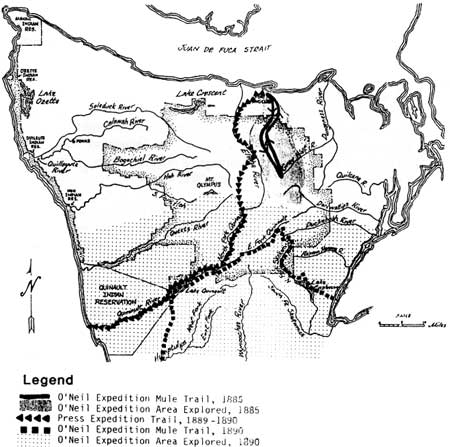

Press Expedition, 1889-1890

In December 1889, a party of six led by James H. Christie, was organized under the sponsorship of the Seattle Press to explore the interior of the Olympic Mountains. Launching the expedition from Port Angeles, they entered the Elwha Valley and spent 4 months exploring that region until the unusually snowy winter was over. They then proceeded to the head of the Elwha Valley, crossed over Low Divide, and traveled down the North Fork of the Quinault to the Pacific Coast in May 1890 (Fig. B4). Christie and Charles Barnes, the expedition's historian, mentioned observing—and often shooting—elk, deer, wolf, wildcat, and bear, as well as seeing tracks of cougar and rabbit (Barnes and Christie 1890). A column titled "Found in the Olympics" that appeared over the name of C. A. Barnes in the 16 July Seattle Press, contained this summary of wildlife:

The mountains are alive with elk, for the most time [sic] very tame. Some bands, however, having been out upon the foothills, and having probably been chased, are more wild. Deer are also plentiful. One goat was seen by the party. Grouse, pheasant and chicken are undoubtedly plentiful, although we saw few, owing to the severity of the season. Beaver and fisher are numerous on the Quinault. Black bear are plentiful during the proper season. We saw one track of a cinamon [sic] bear on the Goldie river. The cougar, or mountain lion, are numerous. We frequently saw their tracks, but never the animal himself. The grey wolf and the wildcat are common (Barnes 1890:20).

|

| Fig. B4. Routes and areas explored by the Press (1889-90) and the O'Neil (1885 and 1890) expeditions. From Evans (1983). |

Barnes does not specify that it was a mountain goat, and, although he is presumably summarizing wildlife found in the Olympics, it is possible the explorers saw a free-ranging goat belonging to a settler in the Elwha or the Quinault Valley. He does not mention where or when or under what circumstances the goat was sighted. Nor is the observation of a goat recorded in his or Christie's diary narrative. The mention of chicken in the next sentence also gives cause to wonder whether Barnes is including domestic animals; there are no prairie chickens in the Olympics. Pheasant were introduced around 1881. Although "cinnamon" is today considered one of the brown color phases of the black bear, Barnes may have thought the bear track he mentioned belonged to a grizzly bear because of its size. There are only black bear on the Olympic Peninsula, and they all exhibit a black color phase.

O'Neil Expeditions, 1885 and 1890

Army Lieutenant Joseph P. O'Neil led two expeditions into the Olympic Mountains. In summer 1885, O'Neil and a small party spent nearly 6 weeks in the mountains south of Port Angeles. From Hurricane Ridge, one group explored the Elwha Valley while another proceeded along the ridge above the Lillian River (Fig. B4). From a base camp, probably in Cameron Basin, O'Neil and another soldier made a reconnaissance southward as far as the vicinity of Mount Anderson. O'Neil recounted hearing the screams of mountain lions close to their camp at night, shooting a marmot, seeing and shooting at several bear, shooting at one large wolf, and encountering numerous bands of elk in the high country (O'Neil 1890). On the route to Mount Anderson, O'Neil traveled through places that have subsequently become prime mountain goat habitat, but he reported none.

O'Neil returned to the Olympic Peninsula in July 1890 to lead a more ambitious expedition from Hood Canal across the southern part of the interior mountains. The expedition included three civilian naturalists: Louis F. Henderson, botanist, teacher, businessman, and graduate of Cornell University; Nelson E. Linsley, mineralogist; and Bernard J. Bretherton, field biologist and curator of the Oregon Alpine Club's museum. During this 3-month expedition, the enlisted men constructed a major mule trail across the southern Olympics, while small parties that included the naturalists fanned out in all directions to explore much of the southern half of the Olympic Peninsula, including an ascent of Mount Olympus (Fig. B4). O'Neil reported later on the wildlife observed:

The game is very plentiful, particularly elk and bear; deer are some what scarce. . . .All the large game seeks the higher altitudes during the midday, but may be found in the valleys morning and evening. . . .Cougar are found in the foothills; I have seen none in the mountains. Beaver, mink, otter, and skunk abound in the valleys. The whistling marmot is found on the rocky mountains sides. A small animal much resembling him, called the mountain beaver, is found in soft places on the mountain sides (O'Neil 1896:19).

In September 1890, a small party, which included the naturalists Linsley and Bretherton and Private Harry Fisher, explored the vicinity of Mount Olympus. Bretherton and Fisher both kept journals. Bretherton's journal contains brief occasional entries. Fisher, who wrote with the idea of publishing, claimed to have kept notes of every day's events. His journal provides a much more complete account of the expedition. During this exploratory mission, Bretherton collected some bird specimens. Several bear were seen, and one was killed on 19 September "but no signs of other game. Elk nor deer had not been in this basin during the summer" (Fisher 1890:207). After climbing Mount Olympus on 22 September, Bretherton made his way down the Queets Valley, where he noted that sand bars along the river contained the tracks of elk, deer, bear, wolf, and otter, but none of these animals was seen. He saw a small beaver dam, shot a duck, and noted the presence of mink and weasels (B. J. Bretherton, Olympic National Park library, unpublished journal, 1890).

Private Harry Fisher's real name was James Hanmore. He had reenlisted under an alias to conceal a dishonorable discharge for drunkeness in 1889. Previous to that his character during a 5-year enlistment had been judged excellent. Fisher often accompanied the expedition's naturalists, took an interest in their observations, and apparently absorbed some of their knowledge of natural history. He described himself as "possessing some abilities as a botanist, mineralogist and assayer" and equipped himself with telescope, microscope, and compass, among other items. He developed a special interest in botany, and after being discharged from the Army in 1891, took up a land claim in the Queets Valley and collected botanical specimens. Fisher's detailed accounts of his activities regularly mention plants and animals observed or hunted in various locations, as in the following account for 7 August, in the high country near the headwaters of the Duckabush River:

Descending into the basin, we examined the organic as well as the inorganic formation with one addition to our herbarium. This was the only spot at which I found watercress in mountain streams and these were very small. . .By perseverance we gained the divide again between the two streams. A very pretty and tall cone overlooked the country and we unstrung our packs and began its ascent. Upon this peak I collected two plants in flower that were entirely strange to me. Leveling the glass I could distinctly make out a deer in the lake playfully splashing water. Further on was the lone calf and higher up was bruin who I have no doubt added this calf to his greed before morning. Completing our sketches we descended to our packs. While adjusting our paraphernalia, a deer was sighted descending below us. Thinking we might find a good route down into Elk basin we allowed it to go undisturbed and followed its trail. While passing over a damp spot a strange wild onion was discovered. Silver skin and of peculiar shape, white blossom and odor was natural. The bulbs grew in clusters as in artichokes, firm and very rich in albumen. . . .A greater portion of the timber was dead at this alt. (perhaps fire had spread). Melting snow from above created a dampness in the soil which was burrowed as thoroughly as a prairie dog town. The inhabitants were a mystery. Marmots were bold and inhabited dry and rocky slopes, generally the track of a rock slide, while these animals chose wet places, frequently irrigating their holes by digging ditches. Their holes were much smaller than the marmot and none of them were ever sighted. We called them mountain farmers from the fact that they gathered grass and herbs, distributing them in regular and even bunches upon logs and rocks to cure. This was done at night and taken in when cured. Whether mountain beaver, wood rats or a species of the marmot we were unable to decide accurately (Fisher 1890:97-99).

Fisher made extensive excursions through areas that are presently inhabited by introduced mountain goats. He stated that he "had kept a vigilant look out for goat and sheep," and was "satisfied that neither are to be found in this range of mountains" (Fisher 1890:217).

The large game of the mountains were elk, bear, of the black species only, white and black tail deer. Along the streams were cougar, otter, beaver, raccoon, mink, wild cat and perhaps wolves but none were sighted by our party. Among the ground animals were the marmot. . .and the smaller mountain farmer, perhaps a mountain beaver, whose habits and appearance we learned but little of. Chipmunks were plentiful and some gray squirrels. All varieties of grouse were represented but no pheasant (Fisher 1890:217).

Fisher reported both white and black-tailed deer. Although white-tailed deer do not occur now on the peninsula or in the Puget Sound lowlands, small populations occurred historically (Suckley and Cooper 1860). A white-tailed deer specimen (serial no. 00067407) taken by C. P. Streator on 4 July 1894 at Lake Cushman is in the National Museum of Natural History. The closest extant white-tailed deer population occupies a small area on the lower Columbia River. Although the two squirrels commonly found in the Olympics are Douglas squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasii) and northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus), Fisher could have seen gray squirrels (Sciurus griseus) in the southern part of the peninsula where there were oak trees.

O'Neil's second expedition explored areas in the eastern Olympics that have supported high densities of mountain goats in recent years. As Governor Semple and early naturalists observed regarding the mountain goats in the Cascades, these large white animals are "gregarious. . .and readily noticed in the distance." It seems likely, therefore, that if goats had been present, Fisher, keeping a "vigilant lookout" with his telescope over a period of 3 months, would have spotted some.

James Wickersham's Excursions, 1889 and 1890

Not much is known about Judge James Wickersham's trip into the Olympics in the summer of 1889, although the Seattle Press reported in its 16 July 1890 issue that Wickersham and another man had traveled about 20 miles up the Skokomish River (Fig. B3). Wickersham, however, did leave an account of his outing into the eastern Olympics during July and August 1890. His party, which consisted of friends and family members, took 20 days to cover what he estimated to be a 125-mile trip into the upper reaches of the Skokomish, Duckabush, and Dosewallips watersheds. Wickersham specifically mentioned seeing and killing a marmot, seeing a bear and cub and killing the bear, and estimated that there were 300 elk (a low estimate) remaining in the Olympics, as well as deer. He generalized

Bear, elk, deer, and cougar, wild cat, beaver, and many smaller animals are numerous, while the streams and lakes are filled with trout and salmon—a veritable hunter's and fisherman's paradise (Wickersham 1961:13).

After spending 3 weeks climbing peaks in the eastern Olympic Mountains and camping in high mountain meadows in areas now inhabited by numerous goats, Wickersham did not mention observing mountain goats.

Other Explorations, 1880's-1890's

As the Press Party expedition of 1889-90 was being dramatized in the Seattle Press, other Puget Sound area newspapers capitalized on the popularity of Olympic exploration and reported on various expeditions into the mountains. Norman R. Smith, a Port Angeles resident who had accompanied O'Neil's 1885 expedition into the foothills of Mount Angeles, was reported to have done surveying for possible railroad routes from Clallam Bay to Quillayute (La Push) and from Port Townsend to Union City in 1882. He reportedly explored from Quilcene Bay into the Jupiter Hills in 1881 and from time to time was reported to have made other explorations in "innumerable directions." According to Smith,

The principal game is elk, deer and black bear. There are also the panther, cougar, mountain lion and an occasional wolf. There used to be very many wolves, but they have nearly all been poisoned by the settlers (Seattle Post-Intelligencer 1890).

John Conrad gave an account of the explorations of five prospectors who spent 24 days exploring the Olympics. The account is based on a diary kept by A. D. Olmstead who, along with Conrad, was one of the five. Their trip began on 19 June, shortly before O'Neil's second expedition. Beginning on the east side of the peninsula, they hiked up the Dosewallips River valley, followed the divide between the Dosewallips and the Elwha watersheds, and descended into the Elwha Valley where they came upon the Press expedition trail, which they followed out of the Olympics. They reported abundant bear, cougar, elk, deer, "woodchucks," and grouse, and killed four bears, five elk, and five deer. They did not mention mountain goats (Conrad 1890).

In July 1896, a party consisting of Frank Reid, Roland Hopper, Edward Munn, and Fred Church, who had accompanied the O'Neil 1890 expedition, traveled the O'Neil trail from Hood Canal to the Pacific. They built a cabin near Marmot Lake at the head of the Duckabush (about 1,371 m) and camped there for 3 weeks. They shot elk, bear, and a fisher and also reported deer and blue grouse. In the Quinault Valley they noted signs of bear, elk, and cougar "everywhere" but didn't see any game. They did not mention mountain goats (Anonymous 1896).

Also in July 1896, a party of five left Lake Cushman and followed the O'Neil trail up the Skokomish Valley to the divide between the Skokomish and the Duckabush drainages, where they camped for a week before moving to a camp at Marmot Lake. From these camps they made several exploratory trips, including one into the Quinault Valley, and one attempting to locate a route down the South Fork Skokomish River. They reported seeing bands of elk, shooting one, and seeing signs of deer, bear, wolf, and cougar. They saw many marmots and, in the Quinault Valley, a beaver (Castor canadensis). While camping, they ate grouse. They did not mention mountain goats (Maring 1898).

The Mountaineers, 1907

In 1907, and again in 1913, 1920, and 1926, the Mountaineers of Seattle organized outings into the Olympics. In late July 1907, a large group of more than 60 hikers set out to climb all three peaks of Mount Olympus and several members reached the summits. Preparations for, and accounts of, this excursion were extensively written up in the Mountaineers' publication, as were descriptive accounts of the Olympics in succeeding issues of the Mountaineer. The club's outings involved cross-Olympic hikes following the Press and O'Neil trails and ascents of peaks in the Olympic range. None of the articles provided extensive wildlife observations. Animals mentioned are deer, bear, cougar, and elk. An article appearing in the Mountaineer just before the Mountaineers' 1907 expedition summarizes other explorations of the Olympics and mentions that one goat was seen by the Press Party in 1890, citing Barnes's summary in the 16 July 1890 Seattle Press (Hanna 1907).

Observations by Local Residents, Naturalists, and Recreationists

Several residents of the Olympic Peninsula who were closely acquainted with the natural resources of the mountains and forests during many years have provided valuable published and unpublished accounts of the wildlife.

Grant and Will Humes, 1897-1934

The Humes brothers maintained a homestead on a bench above the Elwha River near Idaho Creek and made a living by hunting, trapping, and guiding and packing into the Olympics for recreational parties. Will moved back to New York State around 1916, while Grant remained in the Elwha Valley for the rest of his life (until 1934). Will and especially Grant wrote long, descriptive letters about their seasonal activities, hunting and commercial guiding trips into the mountains, wildlife observations, and tallies of animals trapped or shot by them and other area hunters and trappers such as Billy Everett and Dewey Sisson. Grant sometimes hunted on commission for specimens of particular game animals. His letters mention hunting and trapping cougar, bear, elk, deer, bobcat, wolf, marten, fisher, mink (Mustela vison), raccoon (Procyon lotor), and skunk—most of the major game and furbearing mammals on the Olympic Peninsula. The Humes brothers made many trips into the interior mountains to hunt and trap and to guide and pack for sportsmen, including trips to Mount Olympus in 1905, 1907, and 1919. They constructed many of the trails in the Elwha Valley. Grant Humes probably knew the terrain and animals of the Olympics as well as anyone could at that time and was a keen observer of nature, a photographer, and an articulate writer of descriptive accounts of what he saw. During his almost 35 years of living and traveling in the Olympic Mountains, he did not mention having seen or heard of a mountain goat in any of a collection of 132 letters (Grant W. Humes, Olympic National Park library, unpublished letters, 1897-1934).

Albert B. Reagan, 1905-1909

Albert Reagan was an Indian agent and school teacher from 1905 to 1909 at La Push at the mouth of the Quillayute River on the Pacific Coast. He held a bachelor of science degree from Valparaiso University and bachelor and master of arts degrees from the University of Indiana. Years later, after retiring from the Indian Service, he earned a Ph.D. in geology from Stanford University. While living on the Olympic Peninsula, he wrote several scholarly and popular articles on ethnographic, archaeological, and natural history subjects. In 1908, Reagan wrote a lengthy article on the natural history of the Olympic Peninsula. He listed the game animals of the Peninsula as follows:

In this region is to be found an abundance of game. Deer and elk are plentiful; wildcats, panthers and black bears are numerous; ducks and pheasants stay throughout the year, and the islands of the coast swarm with sea fowl; and the finest salmon and trout on the coast abound in the numerous streams (Reagan 1909b: 137).

Reagan made a more inclusive list of animals of the Olympic Peninsula, based on 3 years of observation "as time would permit" in the high country around the headwaters of the Soleduck River and in the Happy Lake area, as well as in lowland and coastal areas (Reagan 1909a): Douglas squirrel; Townsend's chipmunk; another chipmunk, Tamias caurinus Merriam; Olympic marmot; flying squirrel; mountain beaver; a mouse, Peromyscus akeleyi Elliot; wood rat; another mouse, Erotomys nivarius Bailey; three species of vole; gopher; kangaroo mouse; shrew; "Washington rabbit," Lepus washingtoni Baird; Roosevelt elk; black-tailed deer; bobcat; coyote; gray wolf; black bear; fisher; pine marten; mink; two species of weasel; river otter; spotted skunk; striped skunk; mole; rat; sea otter; sea lion; and hair seal. He did not list mountain goat.

However, Reagan did include mountain goat among animal, fish, and plant remains found in coastal middens in the vicinity of La Push. He listed among the bones of animals identified "elk, big horn, mountain goat, black bear, Putorius, species?, black-tailed deer, wild cat, beaver, raccoon and otter" (Reagan 19 17:16). He stated in a footnote that the remains of the bighorn sheep and mountain goat "are found usually only in the ladle form of the horns," suggesting that these manufactured items were probably acquired by the Indians through trade (see Schalk 1993:21-22).

Chris Morgenroth, 1890-1927

Chris Morgenroth homesteaded in the Bogachiel Valley in 1890. He began working for the Olympic Forest Reserve in 1903 and continued with Olympic National Forest until 1927. During the earlier years and while working for the Forest Service, Morgenroth explored and hunted over much of the Olympic Peninsula. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer on 24 February 1913 described Morgenroth as someone who "knows every nook and corner of the Olympics" (Morgenroth 1991:127). In an autobiography published by his daughter, the forest ranger related many of his experiences in the Olympics, including hunting trips, observations, and encounters with wildlife. In this material, he never mentioned the presence of mountain goats in the Olympics before their introduction. In fact, for many years before their introduction, he had advocated bringing either mountain sheep or mountain goats into the Olympics. In 1908, Morgenroth prepared a summary report on Olympic National Forest. In a discussion of game animals he included elk, deer, grouse, pheasants, black bear, wild cats, wolves, cougars, and "a large variety of smaller fur bearing animals." In this report, he suggested, "It would be advisable to stock the forest with a few mountain sheep[;] they would undoubtedly thrive in the higher altitudes" (Morgenroth 1908:20). It is unlikely he would have made such a comment if mountain goats already inhabited the Olympic Mountains. When goats were introduced in 1925, Morgenroth was one of the individuals present at their release near Mount Storm King.

E. B. Webster, 1910's-1920's

Edward B. Webster was a Port Angeles resident, newspaper publisher, and avid outdoorsman. In 1917, he estimated that since 1900 he had made 220 trips to timberline in the Olympics, 176 of which had been to the summit of Mount Angeles (Webster 1917). Many of the trips had been for 1, 2, or 3 weeks each. In 1920, Webster published a book on the mammals of the Olympic Peninsula. The book won high praise from naturalists, including C. Hart Merriam, former chief of the U.S. Biological Survey. Webster stated positively that "the fauna of the Olympic Mountains. . .has never included the Mountain Goat" (Webster 1920:146). While Webster was its president, a local hiking group—the Klahhane Club—supported the introduction of mountain goats and the establishment of a game sanctuary on Mount Angeles, in part to provide a home for the goats once they were introduced, though they were not initially released there. Webster (1925, 1932) published articles documenting the introduction and subsequent observations of mountain goats on the Olympic Peninsula.

Leroy Smith, 1910's-1950

Leroy Smith, a long-time resident of the Olympic Peninsula, wrote an account of pioneering on the peninsula. He described early hunting and trapping experiences extending over about 35 years. He related having hunted most of the major mammals on the peninsula and did not mention the presence of mountain goats (Smith 1977).

Essays on mountain goats and mountain goat hunting appear in late nineteenth-early twentieth-century books and periodicals on natural history, sport hunting, and recreation. Several are by authors such as James C. Merrill (1880); John Fannin, curator of the Provincial Museum in Victoria, British Columbia and George Bird Grinnell (Fannin and Grinnell 1890); William T. Hornaday (1904), director of the New York Zoological Park; and Ernest Thompson Seton (1909). The mountain goat was known to inhabit the Rocky Mountains of western Montana, eastern Idaho, and British Columbia, the Cascade Range in Washington, and the Coast Range of British Columbia and Alaska. None of the many references searched mentioned the possibility of observing or hunting mountain goats in the Olympic Mountains. Madison Grant stated

The true Oreamnos montanus extends from about the Canadian boundary, south through Washington and into Oregon. In the '70's a considerable number were found on Mt. Ranier [sic] in Washington, and they still occur on Mt. Baker to the northward. It is absent, however, from the Olympic Mountains, from Vancouver Island and from the southern Cascades in Oregon (Grant 1905:236).

Biological and Administrative Surveys

Clark P. Streator, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1894

In June and July 1894, Clark P. Streator of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Division of Ornithology and Mammalogy, spent 3 weeks collecting mammals in the Lake Cushman area. He mentioned a trip to Mount Ellinor, where he heard marmot whistles amidst craggy terrain and caught a marmot in a snow basin. He made notes on whether animals reported to be present were common or not, noted signs and other evidence of animals he did not actually see, mentioned shooting a deer and a bear, and reported that he did not see any elk (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Box 103, Record Unit 7176, unpublished 1860-1961 field reports). He did not mention mountain goats.

Bernard J. Bretherton, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1894

Bernard J. Bretherton, who had been a naturalist on Lieutenant O'Neil's 1890 expedition, returned to the eastern Olympics in August-September 1894 as a collector for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Bretherton's month-long itinerary is not well detailed; his journal notes are mainly a listing of small mammal specimen numbers and measurements. He followed the O'Neil route along the North Fork of the Skokomish River, going as far as 3 miles northwest of Mount Steel, to an elevation of about 1,500 m. He noted locations where he trapped a mountain beaver and a marmot "kitten" and altogether collected almost 90 specimens of small mammals and birds (B. J. Bretherton, Olympic National Park library, unpublished collector's records, 1890-98). Part of his route passed through habitat now occupied by goats. Bretherton made no mention of seeing any large mammals on this trip.

C. Hart Merriam and Biological Survey Members, 1888 and 1897

Clinton Hart Merriam was the first chief of the U.S. Biological Survey (which later became the Fish and Wildlife Service), and for 25 years he directed the course of investigations of North American mammalian fauna. Merriam developed the concept of "life zones" represented by characteristic communities of plants and animals that varied with changes in altitude in mountainous areas. Description of these life zones became the mission of the Biological Survey under Merriam.

In 1888, Merriam spent about 2 weeks in the Puget Sound area observing and collecting small mammals and birds near Port Townsend and Neah Bay on the Olympic Peninsula and visiting the Provincial Museum in Victoria. He spent from 31 August to 4 September at Neah Bay, wandering in the woods, setting traps, and querying residents about the local fauna. There he noted the presence of Ursus americanus (black bear), Mephitis (striped skunk), Spilogale interrupta (spotted skunk), Lutra canadensis (river otter), Lutreola vison (mink), Putorius (longicauda?; long-tailed weasel), Sorex (shrew), Sciurus douglasi (Douglas squirrel), Tamias townsendi (Townsend chipmunk), and Hesperomys arcticus (white-footed mouse). Merriam also made notes in his field journals of what species were not present at locations he visited. He mentioned that "there are no Porcupines, Muskrats, or Rats near Neah Bay, and the Indians do not know any such animals. Deer and Elk occur a few miles back in the deep forests. Caribou are not known on this side of the Strait" (C. Hart Merriam, Papers of C. Hart Merriam—Box 4, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, unpublished journal, 1888:51).

Merriam visited the Olympic Peninsula again during the last week in August 1897, accompanied by Vernon Bailey, a member of the Biological Survey. Merriam and Bailey traveled up the Soleduck Valley in the northern Olympics to an estimated elevation of about 1,400 m, just below High Divide in Seven Lakes Basin. They camped in this area for 3 nights and collected specimens of marmots, chipmunks, and mice; explored the head of the Bogachiel Valley; shot at a bear and her two cubs near their camp; and also observed an Aplodontia (mountain beaver) colony not far from camp. Merriam did not see any elk, although he saw trails and plenty of tracks. Merriam had seen several heads and a few hides of Olympic elk while in the region and made arrangements with local hunters to secure specimens for him later in the year after the elk had put on winter pelage. A specimen sent to him from the Olympic Peninsula later that year became the type specimen for the Roosevelt elk (Merriam 1897). Merriam noted in his field journal that animals "said not to occur in the Olympics are Sheep, Goats, Porcupines, Coyotes, Foxes, Grisly [sic] Bear" (C. Hart Merriam, Papers of C. Hart Merriam—Box 6, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, unpublished journal, 1897:36).

Merriam, having spent 2 weeks at Mount Rainier before coming to the Olympics, was interested in the differences in plants and animals found in these two locales. Merriam's papers at the Bancroft Library include several pages of notes listing plants and animals that he found on Mount Rainier but did not find in the Olympics. In a typed manuscript, Merriam explored the reasons for these differences:

The gap that separates the Olympic Mountains from the Cascade Range, the only other mountains of the region, is only about a hundred miles wide and is filled by the dense forest already mentioned, affording continuity of range for species inhabiting the mixed Transition and Canadian zones, but the higher parts of the Olympics, falling within the Hudsonian and Alpine zones, have been disconnected from corresponding zones to the north and east for at least several million years, a period long enough to admit a considerable amount of differentiation in the species stranded here... Contrasting the faunas and floras of the two regions, some highly interesting differences appear. The flora of the Olympics is rich and varied and comprises a number of types not known from the Cascade Range. The fauna, on the other hand, at least as far as the land vertebrates are concerned, is rather meagre and is not known to include a single specific type not found in the Cascades. . . .Among mammals, perhaps the most striking peculiarity of the region is the species it lacks. There are no Mountain Sheep, Goats, Porcupines, Coyotes, Foxes, or Grizzly Bears in the Olympics (Merriam, undated manuscripts "The Olympic Forests" and "The Olympic Mountains").

Merriam's papers at the Bancroft Library contain a popular article on the mountain goat authored by Merriam (the periodical in which it appeared is not identified) and an article by him on the taxonomy of the mountain goat (Merriam 1895) showing Merriam's particular interest in this animal. The popular article identifies the range of the mountain goat as extending from the Rocky Mountains in Idaho and the Cascades in Washington north through British Columbia and the coast ranges of Alaska to the Kenai Peninsula. It does not include the Olympic Peninsula.

In May and June 1897, Edward A. Preble and R. T. Young of the U.S. Biological Survey also visited the Olympic Peninsula. Their observations and collecting activities, however, were confined to birds and small mammals on the western side of the peninsula, in the vicinity of Neah Bay, La Push, and Quinault.

Field Columbian Museum Expedition, 1898

In July 1898, a party from the Field Columbian Museum (Field Museum of Natural History) of Chicago arrived to spend about 3 months collecting animal specimens in the Olympics. They particularly wanted to find Roosevelt elk in their summer range in the interior mountains. They camped in the Elwha Valley, then spent 3 weeks at Happy Lake collecting mainly small mammals before moving to the vicinity of nearby Boulder Lake, at an elevation of about 1,300 m. "The summits on the south of this lake were so broken by jagged ridges, impassible [sic] ravines, snowfields of uncertain depths and yawning chasms, that progress in any direction was out of the question" (Elliot 1899:245)—that is, it was good mountain goat habitat. They also visited the upper Soleduck Valley and the Bogachiel Valley where they obtained five specimens of elk. Altogether the expedition collected between 500 and 600 specimens, "with few exceptions embracing all the species known to inhabit the region," including elk, deer, and bear (Elliot 1899:246). D. G. Elliot, curator of mammals, described 30 species and subspecies of mammals from the Olympic Mountains. The mountain goat was not included nor was it mentioned as one of those few exceptions. Elliot, like Merriam, demonstrated a special interest in the mountain goat, describing the Alaska form of the goat as a new species in 1900 (Elliot 1900).

State of Washington, 1898

In 1898, the state fish commissioner (who was also the ex officio state game warden) reported on the status of ungulates in western Washington, listing deer, elk, mountain sheep, and mountain goats as present in the Cascade Mountains and only deer and elk as present in the Olympic Mountains.

The section within the limits of the Cascade mountains and contiguous territory contains great numbers of several varieties of deer and a limited number of elks, mountain goats, and mountain sheep. The western part of the state, within the section embraced by the Olympic mountains and its spurs, contains a great many elks and deer of several varieties (Little 1898, cited in Schullery 1984:38).

U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Forest Service, 1897-1925

In 1897, much of the Olympic Peninsula was set aside in the Olympic Forest Reserve. During 1898-99, Arthur Dodwell and Theodore Rixon surveyed the reserve, but the focus of their report was topography and soils and especially the types and quantity of timber found on the Olympic Peninsula rather than wildlife (Dodwell and Rixon 1900). The Olympic Forest Reserve became Olympic National Forest in 1907. Ranger Chris Morgenroth (see above) prepared a report (1908) enumerating the major types of game animals in Olympic National Forest, which did not include mountain goats. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Victor B. Scheffer compiled an "estimated wildlife census" of mammals in Olympic National Forest based on figures reported by rangers in annual wildlife reports beginning in 1918. No mountain goats were sighted until two goats were listed in 1929, 4 years after the first release of goats (Scheffer 1949). Scheffer included mountain goats among 11 species of mammals that, although they were found in the Cascades and might logically be expected to occur also in the Olympics, were not present because the intervening lowlands of Puget Sound have presented a barrier to their dispersal since the end of the last glaciation. Scheffer noted, however, that goats had been introduced more recently by sportsmen and game managers.

U.S. Biological Survey, 1917-1921

From 1917 through 1921, several members of the U.S. Biological Survey carried out investigations in Washington State (Hall 1932). In 1918, Vernon Bailey visited the Olympic Mountains in April and May, stopping in the Elwha Valley at Humes ranch and hiking up the Hoh Valley. In 1921, Walter P. Taylor and George C. Cantwell (who had been custodian of the federal bird refuges off the coast of the peninsula), William T. Shaw, Harold St. John (of Washington State University), and W. G. Cassels spent from late June until early September exploring the Olympic Mountains, visiting the Elwha Valley, Hurricane Ridge, Happy Lake and Boulder Lake, the headwaters of the Elwha, Dosewallips, and Quinault rivers, and the Soleduck and Hoh valleys. Their itinerary included 5 days above timberline at the head of Little River and on Hurricane Ridge and 5 days in the vicinity of the headwaters of the Dosewallips, both areas that have recently been frequented by goats. Bailey, Taylor, and Cantwell submitted reports on the mammals of the Olympic Mountains. Taylor's field report lists 40 species of animals observed in the Olympics, including notes on where they were seen or collected. It also included where they were seen or taken by local informants, including their packer, Oscar Peterson, Billy Everett (who owned Olympic Hot Springs), Chris Morgenroth (forest ranger), Grant Humes, William Stewart (U.S. Forest Service fire guard and "veteran trapper"), and E. B. Webster, all of whom knew the Olympics intimately (USFWS circa 1860-1961, Box 104). Cantwell's report discusses 37 (mostly the same) species (USFWS circa 1860-1961, Box 100). None of these reports mentions mountain goats in the Olympics.

W. P. Taylor was familiar with various locations of mountain goats in Washington State. In 1919, Taylor made extensive wildlife observations on Mount Rainier. His field notes contained lengthy observations on mountain goats, including not only goat sightings but also observations of goat tracks, droppings, and trails (USFWS circa 1860-1961, Box 104). J. B. Flett, Mount Rainier naturalist, told Taylor about other areas in western Washington where he had observed goats, mentioning Mount St. Helens and Goat Rocks. Flett had made his first trip into the Olympics in 1897, and he recounted bear observations in the Olympics to Taylor. It seems likely that if Flett had observed goats in the Olympics, he would also have related this information to Taylor. Also, given the thoroughness of Taylor's goat observations on Mount Rainier, it seems likely that if there had been any traces of mountain goats in the Olympics, he would have noted them. Taylor and Shaw (1929) defined the range of the mountain goat in Washington State as the Cascade Mountains north to the Canadian border, south at least to Goat Rocks, east to the vicinity of Lake Chelan, and west to Mount Baker and Mount Rainier. The subspecies, Oreamnos americanus missoulae, was reported to have once occurred in the Blue Mountains in the southeastern part of the state, but W. Dalquest expressed the opinion that this report was based on a misidentification (Dalquest 1948:406).

F. M. Gaige, 1919

In July and August 1919, F. M. Gaige of the University of Michigan-Walker Expedition collected 131 mammal specimens in the vicinity of Lake Cushman, including a few that were collected on a short trip to Mt. Steel. Gaige collected only small mammals. Most were taken near the post office at Lake Cushman at an elevation of about 174 m (Dice 1932).

State of Washington, 1938-1940

In its fourth biennial report, the Washington State Game Commission stated that a study of mountain goats had been conducted during the biennium by a department biologist. "Previously the Department had little conclusive data available on the habits, habitat and rate of reproduction of this animal" (Washington State Game Commission 1940:72). The mountain goat study, written by Niilo A. Anderson, states

No mountain goats are native to the Olympic Mountains, but two forms have been planted there and are reported to be increasing in numbers. Of these, four animals of the form Oreamnos americanus columbiae were introduced from Banff, Alberta, in 1924 [1 January 1925], and eight animals of the Oreamnos americanus kennedyi group were introduced from Alaska and released in 1929 and 1930 (Anderson 1940:2).

For an account of the introduction of mountain goats into the Olympic Mountains and their subsequent dispersal, see Webster (1925, 1932) and Moorhead and Stevens (1982).

Discussion

Historical records of wildlife observations on the Olympic Peninsula include conflicting reports concerning the presence of mountain goats. Spanish explorers (Wagner 1933), Gilman (1896), and a newspaper summary of the Press Expedition (Barnes 1890) mentioned that goats were present. In addition, several nineteenth-century observers (Dunn 1845; Wilkes 1845; Bancroft 1875; Gibbs 1877; Pickering 1895) as well as the Spanish explorers (Jane 1802) and Vancouver (Meany 1907) mentioned the use of mountain goat wool by Native Americans in the Puget Sound region. On the other hand, at least four other pre-1925 discussions of Olympic Peninsula wildlife (Fisher 1890; Merriam 1897b; Grant 1905; Webster 1920) state positively that goats were not present. Three of these authors had explored the Olympic Mountains. Early naturalists describing the known range of mountain goats in North America do not include the Olympics (e.g., Fannin 1890; Hornaday 1904; Seton 1909). Several biologists writing about Washington mammals after the 1920's state that mountain goats were introduced to the Olympic Mountains (Anderson 1940; Scheffer 1949; Johnson 1983). The remainder of the reports by recreationists and wildlife biologists that list Olympic mammals do not include goats.