|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Grizzlies of Mount McKinley |

|

CHAPTER 10:

Grizzlies and Man

Not surprisingly in an area like McKinley National Park where grizzlies are plentiful and people visit in increasing numbers, interactions between these two species are frequent. Many interactions end amiably, with neither participant suffering unduly. At other times, the people involved may gain a thrill from an imagined charge or being close to a grizzly, but the bear, seemingly untroubled by the encounter, may suffer in the long run. It may be scared away from a choice part of its feeding range, a relatively minor irritation perhaps, but more serious is the effect such an experience may have on predisposing the bear to future encounters that might result in a less innocuous outcome. Those acquainted with bears probably would agree that a tame bear is more dangerous than an unspoiled one in the wilderness.

The encounters we hear about most are those resulting in injury to the people involved, but these cases are a small proportion of all interactions. Herrero (1970) has analyzed cases of human injuries resulting from grizzly encounters, and elsewhere (Murie 1961) I have discussed grizzly relationships with man and recounted a number of incidents in McKinley National Park. Hence I shall consider the subject only briefly here.

In recent years my file on grizzly encounters in McKinley National Park has grown. More and more photographers have taken pictures of grizzlies, and their zeal for "filling the frame" sometimes has resulted in unsettling moments for them. In the spring of 1967 a moose carcass near Savage River attracted several bears, a wolf, and a wolverine over a period of several days. An eager photographer set up his tripod near the carcass hoping for a picture of a mother bear with two 2-year-old cubs that had been feeding on the carcass for several days. This family approached the carcass, saw the man nearby, and all three charged to within 6 feet before his shouting took effect and they all turned and galloped away. The bears did not have the man's scent from their position so perhaps did not realize at first what they were charging. They may have thought he was a wolf; one had been at the carcass earlier in the day and its scent may have remained in sufficient strength to cause such a mistake. Fortunately, in this and similar incidents, the grizzlies involved were not so accustomed to man that they had lost their usual reaction to him, namely, fleeing, even here when they may have felt their cache was in jeopardy (Fig. 60).

|

| Fig. 60. Photographers, in their zeal for "filling the frame," sometimes experience unsettling moments. |

Another incident is worth noting because the bear attack was unprovoked. On 4 August 1961, at 3:50 p.m., an ecologist, Napier Shelton, was near the timberline on a slope of Igloo Mountain taking increment borings, when he heard an ominous growl. About 10 yards away he saw a grizzly coming through the willows and climbed up the tree he was working on which had a 14-inch butt and was 25 feet tall. It was an easy tree to climb because it had a slight downhill slant and rather stout, horizontal limbs that reached almost to the ground. Using the horizontal limbs, the bear was able to paw his way up, and, grabbing Nape's heel, clamped down on the calf of his leg, making deep tooth wounds. Nape hung on but was pulled down a little when the bear slid to the ground; again the bear managed to clamber up, a little higher than the first time, and bit into the thigh of Nape's other leg. All this time Nape was kicking at the bear with his free leg until the animal let go and slid down to the ground. The bear circled the tree two or three times before moving off. Nape waited in the tree for half an hour before starting down the slope to the road, and it was here that I met him. The bites were deep and one tooth wound had slashed into another. Bleeding was not severe, and he was flown to Fairbanks where the wounds soon healed. The doctor said slyly that he thought he detected a little blueberry juice in one of the wounds!

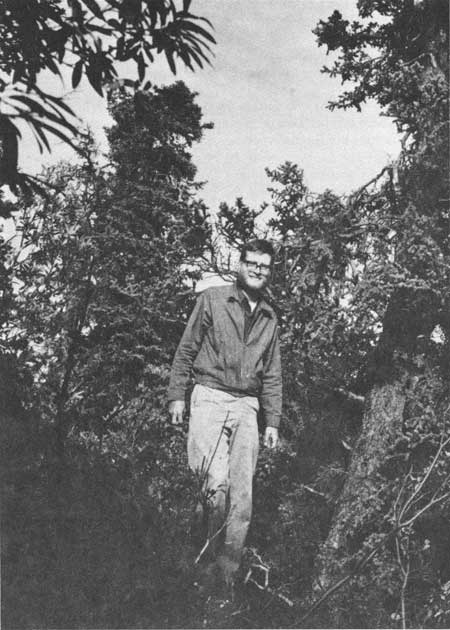

I had been on Igloo Mountain that same day, a little to one side of the spot where this incident occurred, and I had seen a mother bear with two spring cubs across the creek on the lower slope of Cathedral Mountain, almost opposite the site of the attack. These bears disappeared in a ravine and I surmised that they followed it to the creek and climbed up Igloo Mountain. I had seen the bears just a short time before the attack. Thus it seems likely that it was this mother that happened upon Nape in the willow thicket (Fig. 61).

|

| Fig. 61. Napier Shelton, student from Duke University, standing beside a spruce tree where a grizzly attacked him. Shelton climbed the tree and so did the bear, biting him rather severely in both legs. The strong horizontal limbs and slight lean of the tree made it possible for the bear to claw its way up. Picture taken about a week after the encounter. |

The incident illustrates the danger of coming suddenly upon a bear, or vice versa. Many bear incidents in wild country result from encounters at close range where both parties are surprised. It is often easier for the bear to attack than to run.

The other situation to be avoided is interposing oneself between a mother and her cub, even if the distance from the mother seems safe. This action is a serious provocation. In fact, any proximity to a family can be dangerous because it is difficult to know just what will pique the mother.

For some reason the public is unafraid of bears. Perhaps this is because real bears resemble so closely harmless Teddy bears. This attitude is justified to a certain extent because bears, on the whole, are rather good-tempered and well-behaved. But the danger lies in their potentiality for causing serious injuries and the uncertainty of their behavior. A half hearted attack or a casual swipe with a paw can cause a damaging or fatal wound.

When a friend of mine, about to embark into bear country, inquired about the danger of bears, I replied that he had nothing to worry about, that he could travel the wilderness with a light spirit, and that all he needed was faith. The latter, I pointed out, is the chief difficulty. As one gains experience with bears one tends to lose faith, but still if the faith were kept all would be well. The wariest people in the hills are trappers and bear hunters, but after all, they prefer wandering over the hills to crossing a street in modern traffic. The moral is to respect the bear's potential for causing injury and to keep at a respectful distance.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap10.htm

Last Updated: 06-Dec-2007