|

SAGUARO

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 6:

DESCRIPTION AND EVALUATION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES

The following properties possess varying degrees of historical interest. Unfortunately, information was spotty or nonexistent in some instances. Those properties not deemed to have sufficient value to be placed on the National Register of Historic Places should be retained and could play a useful role in the interpretive program.

A. Mining in the Tucson Mountain Unit

The Tucson Mountain Unit partly covered the Amole Mining District where numerous claims were recorded. Nearly all of the location descriptions of these claims are so vague as to make it impossible to establish where they are situated. Although 149 earth disturbances from a few feet to 425 feet deep have been recorded as mining activity in this unit of Saguaro National Monument, only two, the Gould and Mile Wide have any significance. They were the only producing mines. The others were classified as prospect shafts or tunnels which meant that not enough ore was extracted to ship to a smelter. As a result, only the Gould and Mile Wide mines will be nominated to the National Register as typical mines which provoked interest and great expectations for the Amole Mining District. Wayside exhibits could be placed on each of the two sites telling of the activity that occurred there. The remainder of the shafts and prospect holes have no significance.

S.H. Gould established the Gould Copper Mining Company and filed on nineteen claims about 1906 during the period of the greatest rush to stake claims in the Tucson Mountains. Although he did encounter some financial problems during the 1907 depression, a mortgage enabled him to keep his Gould Mine operating. His operation prompted the Arizona Star to declare that his mine showed that the Tucson Mountains had been overlooked as an important copper area. That newspaper proved to be incorrect, for, although Gould managed to recover some 45,000 pounds of copper before he ceased operation in 1911, the profit from the mine was not sufficient to offset the costs. Gould was forced from the company leadership and in 1915 it went bankrupt. From 1911 until it permanently closed in 1954 the mine was operated only sporadically. The 130 tons of ore extracted in the last four months the mine functioned contained only two percent copper and fifty-one ounces of silver. This amount proved too little to allow a small concern to operate. There are no physical descriptions of the number or types of structures associated with the mine or their location. The mine shaft and a shell of the powder house are all that remain (Photos 16 and 17).

|

| Photo 16. Gould Mine Shaft May 1986. Photograph by Berle Clemensen |

|

|

Photo 17. Gould Mine Powder House May 1986.

Photograph by Berle Clemensen

These uncoursed stone walls are of the only remaining structure at the Gould mine site. |

At the turn of the century L. Martin Waer and Pedro Pellon filed several claims in the Amole Mining District among which was the Copper King (later called the Mile Wide). By 1907, when they ceased operation, they had sunk an exploratory shaft to a depth of eighty-six feet without striking any profitable ore. Waer tried to lease the Copper King to the Morgan Consolidated Gold and Copper Mining Company in 1914 without success. The next year, however, Charles Reiniger and J.H. King signed an option to purchase the property along with Waer's other claims. Reiniger established the Mile Wide Copper Company. It was so named because the width of the claims was a mile wide. He concentrated on the Copper King which became known as the Mile Wide Mine. In the process of development Reiniger abandoned Waer's old shaft in favor of a new site up the hill. While mining at that location he reported a copper strike which purportedly would be the equal if not superior to the largest Arizona copper mines. As a result, stock sales increased and Reiniger further developed the property. He built four houses, a work shop, mess house, rock crusher, and mill. [1] In addition he improved the road to make it possible for his six trucks to haul more ore to Tucson for rail shipment to the smelter at Sasco which was just north of Silver Bell.

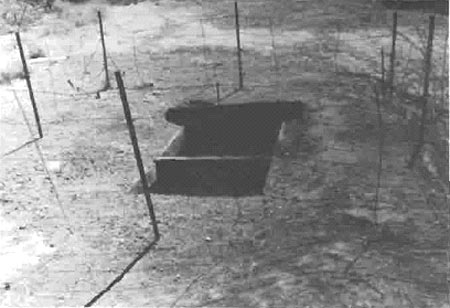

Reiniger used the mining activity and the promotional hype to practice fraud on the stockholders. In late 1919 he disappeared taking half the money derived from stock sales. In addition he sold up to $100,000 of his own stock before his departure. Although the stockholders brought a suit against him and won, the absence of Reiniger forced the company to liquidate its holdings. The real estate was purchased by the Union Copper Company of Pittsburgh and the equipment auctioned for $3,000. That company did some development work, but in 1929 it sold the property to H.S. Diller and Associates of New York. Diller operated the Mile Wide until the depression forced a halt to the operation by the end of 1930. At that point the mine had produced 70,000 pounds of copper valued at $10,000 and $15,000 in silver. Most of that production occurred during the Reiniger period. The Mile Wide opened briefly in late 1942, but L.M. Vreeland and Ralph Campbell, who leased it, managed to ship only four carloads of ore before abandoning it by the end of 1943. It never operated again. Today, all that remains of the mine are the two shafts and the foundations of some of the buildings which Charles Reiniger constructed (Photos 18 and 19).

|

| Photo 18. Mile Wide Mine Upper Shaft May 1986. Photograph by Berle Clemensen |

|

| Photo 19. Mile Wide Mine Tailings May 1986. Photograph by Berle Clemensen |

B. Mining in the Rincon Mountain Unit

A portion of the Rincon Mining District covered part of the Rincon Mountain Unit. As the least of the Pima County mining districts, no known production was ever recorded. Mining activity, however, did occur within the monument boundary and the Loma Verde was the best known of the mines. Numerous prospect holes and some other mine shafts can be found as well. Most of these sites are on the headwaters area of Rincon Creek with several located on the western slope of the Tanque Verde Mountains. Thirty prospect holes in the cactus forest area were filled by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the mid-1930s. Because of the dearth of information on these mines and prospect holes, and since there is no recorded production from them, none merit nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.

C. Lime Manufacturing on Both Saguaro National Monument

Units

Although a number of lime kilns were said to have operated on the monument, the remains of only four kilns (two in each unit) have been identified. Since these kilns represent the remnant of a once active local industry, they are worthy of nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. The two kilns in the Rincon Mountain Unit have been placed on the Arizona State Register of Historic Places.

The beginning date for local lime manufacture cannot be established with certainty although tradition states that the first kilns to operate in the Rincon Unit supplied lime for the construction of Fort Lowell in 1873. This belief was false, for lime was not used at that post until 1882. Lime production probably did not begin much before 1880 as most accounts of Tucson to that time described the village as a collection of unwhitewashed adobe structures. The Southern Pacific Railroad, which reached Tucson from the west in March 1880, promoted prosperity and, therefore, a demand for better housing. Since California lime was advertised for a time after that event, local lime production was probably limited. In fact the first written statements about lime kilns did not appear until the 1890s. Available evidence leads one to the conclusion that one of the two Rincon Unit kilns was possibly built in the 1880s while the second was constructed around the turn of the century. Both ceased operation in 1920. The Tucson Mountain Unit kilns were probably built in the mid-1890s and no longer functioned by 1910.

Each of the kilns was constructed differently. The northernmost one in the Rincon unit was built into the west bank of a north-trending wash with its top at terrace ground level. It is circular in construction and made of coursed adobe. The interior dimension is just over seven feet in diameter (photo 20). The south kiln was also constructed with a circular design into the west bank of the same wash. It, however, was made of angular granite masonry set in mud mortar. It has an interior diameter of about eight feet (photo 21). [2] The southernmost Tucson Mountain Unit kiln, like the others, was circular and built into the south bank of an arroyo. It was made of rubble stone laid without mortar with an interior diameter of seven feet (photo 22). The final kiln was constructed into a small hill. It, too, is circular with an interior diameter of about seven feet. It was made of rubble stone and lined with a double layer of fire brick. A brownish colored mortar was used to set both the stone and brick. All four kilns are in various states of decay. [3]

|

|

Photo 20. North Lime Kiln, Rincon Unit May 1986.

Photograph by Berle Clemensen

This interior picture shows the coursed adobe brick construction. |

|

|

Photo 21. South Lime Kiln, Rincon Unit May 1986.

Photograph by Berle Clemensen

This kiln was made from angular granite masonry set in mud mortar. |

|

|

Photo 22. Lime Kiln near Sus Picnic Ground, Tucson

Mountain Unit May 1986. Photograph by Berle Clemensen

This southernmost of the Tucson Mountain Unit kilns was built of rubble stone laid without mortar. |

The monument kilns are typical of a crude type used in the manufacture of lime. Building them into an embankment so that the top was level with the embankment surface allowed the kilns to be easily charged with limestone and fuel from a wagon. At the same time heat loss would be lessened by having most of the kilns' exterior embedded in earth. The small exposed area away from the embankment provided for the lime removal from the base. As Frank Escalante explained, it took four days to make lime during which time wood would be added every two to three hours. Ten to fifteen cords of green palo verde would be burned in the four days although if that wood were not available green mesquite would be substituted.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sagu/hrs/hrs6.htm

Last Updated: 23-Jun-2005