|

ROCKY MOUNTAIN

The Geologic Story of the Rocky Mountain National Park Colorado |

|

THE PARK AS SEEN FROM THE TRAILS.

Progress is being made toward opening the Rocky Mountain National Park by means of trails, but in so rugged a country it will be a long time before all points are made easily accessible. On the following pages are described only such parts as were seen from trails in use during the summer of 1916.

The village of Estes Park is the center from which radiate many of the trails to the Rocky Mountain National Park. It takes its name from the basin-like opening among the hills which in turn was named for Joel Estes, the first white man to settle here. Prior to his arrival the Arapahoes visited the park frequently and knew it as "The Circle (ta kah ay non)."

From this "circle" as a center I shall "personally conduct" the reader over the several trails and point out to him some of the glories of the mountains. We shall start with the Black Canyon Trail and make our way gradually southward to Wild Basin, which is situated near the southern boundary of the park.

BLACK CANYON TRAIL.

From Estes Park one may go on horseback or on foot up Black Canyon to Lawn Lake, where there is a lodge at which bed and board may be secured. From this point he may go on foot to Hagues Peak, Hallett Glacier, and many other points of interest. On his return to Estes Park he may ride down the glacial gorge of Roaring River through Horseshoe Park and Fall River Valley, thus encircling a small but rather interesting group of mountains.

The Black Canyon Trail passes for several miles through a somewhat open and easily traversed valley. But it grows steeper and more difficult farther up the canyon. On leaving the village we pass close to the Stanley Hotel, which was built at a cost of half a million dollars in 1907, at a time when tourist travel was light and before success was assured by the establishment here of a national playground. From this place there is a superb view of the mountains (Pl. XIV, A), and many an attractive nook may be found among the pines and the granitic rocks which the forces of erosion have shaped in curiously interesting forms (Pl. XIV, B).

|

|

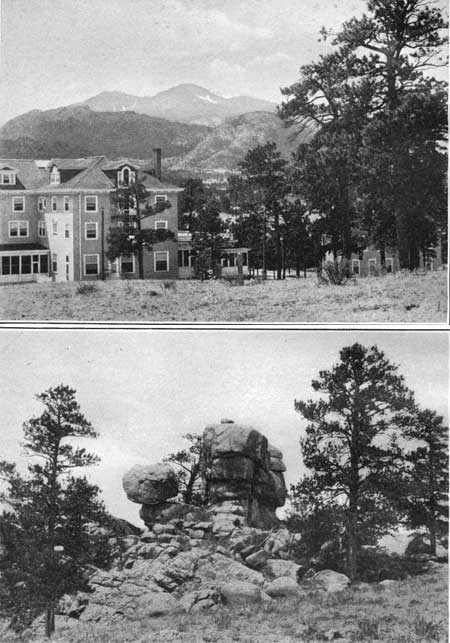

PLATE XIV.

A (top). ESTES PARK AND LONGS PEAK FROM STANLEY HOTEL. B (bottom). A REMNANT OF EROSION IN THE GRANITE OF ESTES PARK. Showing character of weathering. VIEWS NEAR ESTES PARK. Photographs by Willis T. Lee, United States Geological Survey. |

Still farther up the canyon we leave Castle Mountain (8,675 feet) on the left and pass The Needles, or "Little Lumps on Ridge (tha thay-ai ay tha)," as the Indians called these mountains, which reach a maximum altitude of 10,075 feet. The Needles take their name from the sharp pinnacles near the crest. Viewed from below these appear so sharp as to make the name seem singularly appropriate. The broad floor of the valley gives place abruptly to the precipitous side of The Needles (Pl. XV, A, p. 48) in a manner which suggests that this valley was shaped by a glacier. It is not situated in the area occupied by the ice during the last stage of glaciation but may belong to the older stage described on page 31. Some of the needle-like pinnacles are so shaped as to resemble well-known forms when viewed from certain directions. One of the best known is called Twin Owls (Pl. XV, B).

|

|

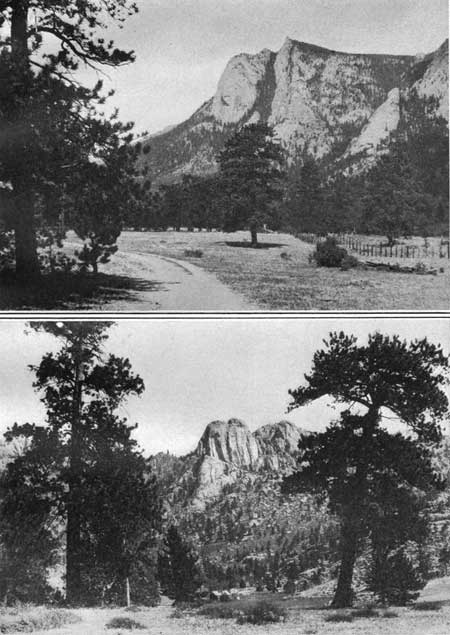

PLATE XV.

A (top). THE SOUTH FACE OF THE NEEDLES.

Precipitous cliffs rising about 2,000 feet above the nearly level floor

of Black Canyon. B (bottom). THE TWIN OWLS, AS SEEN FROM A POINT NEAR STANLEY HOTEL. These remnants of erosion indicate clearly why the Indians called The Needles "Lumpy Ridge." LANDSCAPES IN BLACK CANYON. Photographs by Willis T. Lee, United States Geological Survey. |

About 2-1/2 miles from Estes Park the trail forks, the left-hand prong leading to a waterfall at the intake of the Estes Park water main. The right-hand prong leads up the mountain side toward Lawn Lake. Here we find ourselves on a typical mountain trail in the primeval forest, which winds in and out among the trees, sometimes with scarcely enough room to pass between them. It traverses rocky slopes and passes in some places uncomfortably close to the brinks of dizzy precipices.

Through the thick growth of trees we occasionally catch a glimpse of Bighorn Mountain (11,473 feet) and of McGregor Mountain (10,482 feet), which perpetuates the name of R. O. McGregor, who settled in Black Canyon in 1874. The beautifully rounded summit of the former is caused by concentric shells of the granite peeling off, a process known as exfoliation. Probably the best view of this mountain is obtained from a little parklike opening where beavers have cut away the underbrush and small trees and built a dam.

Just north of Mount Tileston (11,244 feet) the trail reaches a maximum altitude of 11,000 feet. There are few trees to obstruct the view and there are numerous snow banks; but we are shut in between walls of rock until the crest of the wind-swept ridge is reached, where there are no trees to interfere with the superb view (Pl. XVI, A). From this ridge there bursts upon us one of those matchless high mountain scenes which it is quite impossible to describe. We gaze down 400 feet into the bowlder-strewn gorge of a glacier which once occupied the valley of Roaring River. Directly in front lies Lawn Lake, in the center of a great cavity that was gouged out of the mountain side by the ice which gathered for the Roaring River limb of Fall River Glacier (p. 32). Still higher may be seen, though imperfectly from this position, the subsidiary glacial cirque which holds Crystal Lake. To the left stands Mount Fairchild (13,502 feet); to the right Mummy Mountain (13,413 feet); and directly in front the dominating point of the region, Hagues Peak (13,562 feet).

|

|

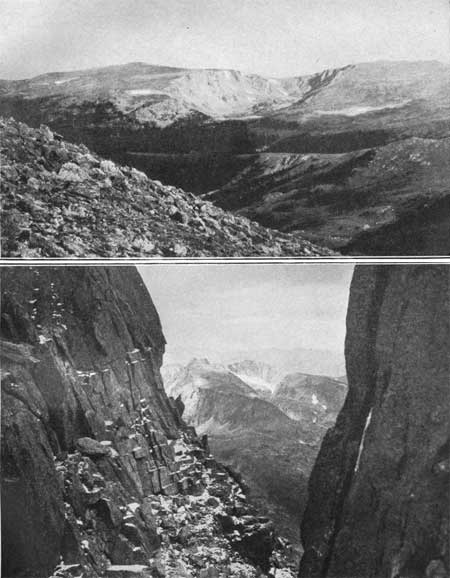

PLATE XVI.

A (top). LAWN LAKE AND THE GLACIAL CIRQUE AT THE HEAD OF ROARING RIVER.

The lake lies near timber line, and the mountains rise more than 4,500

feet above it. B (bottom). HALLETT GLACIER, ABOUT THREE-FOURTHS OF A MILE WIDE, AT THE HEAD OF NORTH FORK OF THOMPSON RIVER. Showing the lake at the foot of the ice caused by the ponding of water back of the moraine which appears in the foreground; remnants of the high-altitude plain (Flattop peneplain) formed by ancient erosion; the white snow of the previous winter, which had not melted from the surface of the glacier by August 25, when the photograph was taken; a part of the old dark-colored, dirty crevassed ice near the center exposed by the melting of the fresh snow; and the approach of the first snowstorm of the winter, which mantled the mountain in white. Photographs by Willis T. Lee, United States Geological Survey. |

LAWN LAKE.

Lawn Lake, which has an area of 65 acres, lies at the bottom of the main cirque at the head of Roaring River. It is one of the many glacial lakes of the park. The size and beauty of this one have been increased by the construction of a dam. In this way the water, which is abundant when the snow is melting early in summer, is held in storage until it is needed on the plains for irrigation later in the summer. The lake lies just below timber line, at an altitude of 10,950 feet; hence tourists are here sheltered by trees while they have every advantage of the unobstructed views usually obtained from points above timber line. In a horizontal distance of little more than a mile from the lake the precipitous walls at the head of the cirque rise more than 2,600 feet above the surface of the water to Hagues Peak and nearly as high on either side.

HAGUES PEAK AND HALLETT GLACIER.

The trip to Hagues Peak and Hallett Glacier is a difficult one and must be made on foot, for the route is too steep and rough for a horse. The start from Lawn Lake should be made early in the morning. We follow a trail for a short distance, then take a bearing to an objective point on the crest of the mountain and work toward it as best we may up the steep bowlder-strewn slope; for here no trail that can be followed has been laid out. Although this trip is as difficult as any other in the national park, we are not unmindful of the glorious panoramas that stretch out before us as far as the eye can reach. Almost at our feet lies Crystal Lake in its rock-walled basin high in the side of Mount Fairchild, and we understand better than before seeing it why such lakes are called "pocket" lakes.

A side trip to the saddle between Hagues Peak and Mount Fairchild is worth all the effort required to obtain the unusual views from this point. Here may be seen the bighorns or wild mountain sheep and flocks of ptarmigan. Slightly to the south of Comanche Peak, partly within and partly north of the Rocky Mountain National Park, may be had an impressive view of a glacial cirque (Pl. XVII, A, p. 50). As the photograph was taken from a distance of about 5 miles, the cirque is shown in its true relation to its surroundings. This hollow, a mile long and half a mile wide, was gouged out of the mountain side by the ice of an ancient glacier to a depth of about 1,000 feet.

|

|

PLATE XVII.

A (top). A GLACIAL CIRQUE.

Situated chiefly above timber line southwest of Comanche Peak, as it

appears from Hagues Peak at a distance of about 5 miles. It is a

depression more than a mile long in the line of vision, half a mile

wide, and 1,000 feet deep. One of the lobes

of the glacier that occupied Cache la Poudre Valley during the later

part of the Great Ice Age gouged into the mountain side and produced

this unusually fine example of a cirque. B (bottom). VIEW THROUGH ONE OF THE NOTCHES IN THE ROCKY CREST ABOVE HALLETT GLACIER. Looking westward into the glacial cirques at the head of one of the tributaries of Cache la Poudre River. Photographs by Willis T. Lee, United States Geological Survey. |

At the top of Hagues Peak are small remnants of the gently rolling plain (the peneplain of the geologist) which once occupied this region. A much larger remnant of this peneplain lies north of the peak. This surface seems nearly horizontal where its edge is seen above Hallett Glacier in the accompanying illustration (Pl. XVI, B, p. 49), but much of the old plain has been destroyed by recent erosion.1 In some places, as between the cirque occupied by Hallett Glacier and the one immediately north of it, the old surface is broken down. The wall separating these two cirques is only a few feet thick at the top and is sharply serrate. Through the notches in this wall may be obtained views into the glacial gorges of the Cache la Poudre drainage area, which are well worth the effort they cost and which some maintain are the most charming to be found in the park (Pl. XVII, B, p. 50).

1When the geologist speaks of recent erosion he means erosion that has been accomplished within the last million years or so.

In order to reach Hallett Glacier we must cross the mountain ridge and descend into the cirque which lies at the head of the North Fork of Thompson River. The climb to the crest of the ridge is exhausting, and a few moments may be spent resting and viewing the entrancing scenes. To the east lies Mount Dunraven, named for the Earl of Dunraven, who came to Estes Park in 1872 and later acquired property there with the intention of establishing a game preserve. Still farther south is Mount Dickinson, named in honor of Anna E. Dickinson, who is said to be the first woman to reach the top of Longs Peak. Toward the west is the sharp ridge of Mummy Mountain, whose face, nearly 2,500 feet high, is so precipitous that it seems to overhang Lawn Lake. Beyond this is the galaxy of peaks and gorges which we are to visit as we traverse the trails farther to the south.

From this ridge there is a view of Hallett Glacier which is not surpassed from any other point (Pl. XVI, B). The glacier is a great crescent-shaped mass of snow and ice partly surrounding a lake about 300 feet in diameter. Its surface rises steeply from the water's edge to the mountain walls. As seen from below the glacier appears to slope steeply down from the south, west, and north, like tiers of seats in an amphitheater. As the ice all moves toward the lake, it moves in a northerly direction from the south and in the opposite direction from the north, while in the center it moves eastward. As the length of a glacier is reckoned by the distance covered by the moving ice from source to melting point, Hallett Glacier is much wider than it is long. This anomaly is perhaps matched for curious interest by the question raised some years ago as to whether this body of ice should be called a glacier, a subject already discussed (see p. 30).

Great interest has been shown in the crevasses of Hallett Glacier. They differ somewhat in their mode of origin from the crevasses of some other glaciers and seem to be caused, partly at least, by the relief of pressure from below due to melting of the ice in the water of the lake. Some of the crevasses are concentric and conform essentially to the outline of the lake, as if large portions of the glacier were seeking to break off and float away with the surface ice which parts from the more massive body as small icebergs (Pl. XVIII).

But the crevasses of the higher slopes seem to be of different origin. Where the surface snow has melted away, the old ice is found deeply fractured. In exceptionally favorable seasons some crevasses open in late summer so wide that they may be entered and examined (Pl. XVIII, upper). A crevasse several hundred feet long was explored in the fall of 1915, to a depth of about 50 feet. But for 15 years prior to that time, according to report, it had not opened wide enough to be accessible.

|

|

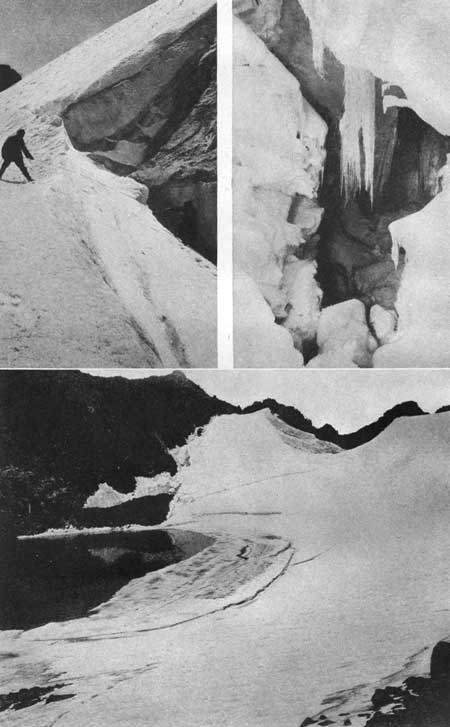

PLATE XVIII. VIEWS AT HALLETT GLACIER. Upper left, Entrance to a crevasse in the ice. This crevasse was explored in 1915 for a distance of 400 feet. Photograph by Frank W. Byerly. Upper right, A view within the crevasse 50 feet below the surface of the ice. Photograph by Frank W. Byerly. Lower, Icebergs breaking away from the foot of Hallett Glacier. Photograph by Willis T. Lee, United States Geological Survey. |

ROARING RIVER.

On leaving Lawn Lake we pass southward for nearly a mile across the wooded floor of the cirque to a small but unusually perfect terminal moraine. It is a crescent-shaped ridge extending across the valley and is composed of rounded bowlders carried by the ancient glacier out of the Lawn Lake cirque and deposited at the end of the melting ice. This moraine is relatively young and marks one of the last stands made by the vanishing glacier, whose retreat may be likened to the withdrawal of a defeated army. In this case the enemies were the warmth of the moderating climate, which forced retreat, and the decrease in snowfall, which cut off supplies. This glacier once filled the valley of Roaring River (see Pl. VIII, p. 30), but was forced back toward the embattled strongholds of the high mountains. A mile south of Lawn Lake it made a final stand, built up a breastwork of bowlders, and maintained its position for a brief period before final extinction.

Farther south the trail angles down the steep slope of the glacial valley. Its east wall is precipitous and the cliffs show marks of ice action up to a height of several hundred feet. The western slopes are now densely forested but probably were once entirely covered with glacial ice which gathered east of the high range that extends from Mount Chapin to Mount Fairchild (see Pl. XIX, A, p. 50). These mountains have been carved by rain, stream, and ice into a group of picturesque gorges, cirques, and pinnacled ridges, but except for places near Ypsilon Lake these points of interest are not easily accessible for want of trails. However, the great peaks of this range are so prominent that they are plainly recognizable from many parts of the park. Ypsilon Mountain is especially attractive and is easily distinguished from all others by the Y inscribed in perpetual snow in its eastern face. At the southern end of this group stands Mount Chapin, whose name perpetuates the memory of F. H. Chapin, the author of "Mountaineering in Colorado," who first visited this region in 1886.

|

|

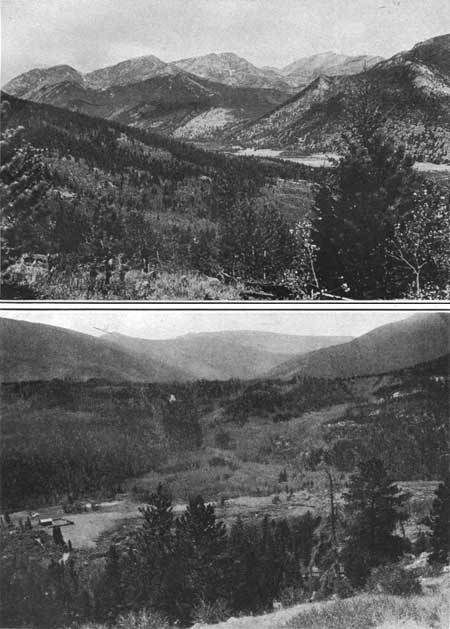

PLATE XIX.

A (top). VIEW FROM HIGH DRIVE ACROSS HORSESHOE PARK TO THE

MOUNTAIN RANGE NORTH OF FALL RIVER.

Including Mount Chapin (12,458 feet), Mount Chiquita (13,052 feet),

Ypsilon Mountain (13,507 feet), and Mount Fairchild (13,502 feet). B (bottom). HORSESHOE PARK AND THE MORAINE SOUTH OF IT. The even-crested morainal ridge in the middle ground was formed at the south edge of the Fall River Glacier, 900 feet above the floor of the melting basin. It was built across a tributary valley, as shown in the background, deflecting the stream southward (to the left) nearly 2 miles. Photographs by Willis T. Lee, United States Geological Survey. |

HORSESHOE FALLS.

The main mass of Fall River Glacier (Pl. VIII, p. 30) occupied the valley of Fall River and eroded this valley much more extensively than the eastern lobe of this glacier eroded the valley of Roaring River. Hence Roaring River occupies what is called a "hanging valley"—that is its floor lies at a higher level than that of the valley into which it empties. In its descent of 500 feet from this hanging valley Roaring River forms a succession of picturesque rapids and waterfalls, known collectively as Horseshoe Falls (Pl. XX).

|

|

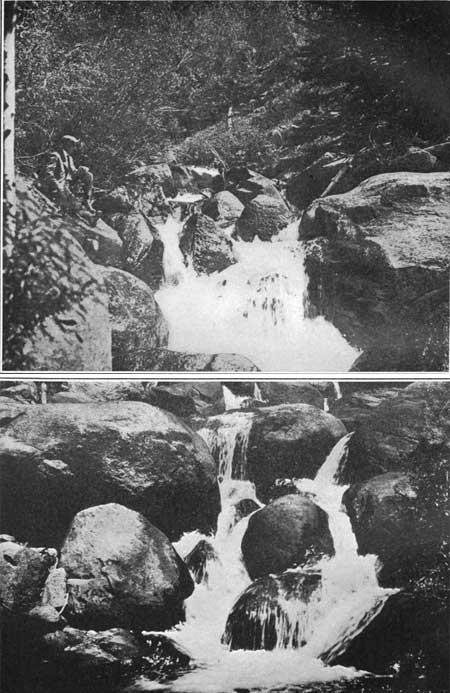

PLATE XX.

A (top). HORSESHOE FALLS, ROARING RIVER.

The stream plunges through the dark recesses of its wooded gorge over

and among the glacial bowlders in a descent of 500 feet from its hanging

valley to

Fall River. B (bottom). RAPIDS NEAR HORSESHOE FALLS. Showing great bowlders of granite deposited here by the ancient glaciers. Photographs by Willis T. Lee, United States Geological Survey. |

There are great numbers of glacial bowlders along Roaring River, and as the water descends over these it is buffeted and torn and lashed into spray. The slopes on either side of the stream are densely wooded, and as we follow the winding trail through the woods and among the rocks the ever-changing scene holds many a pleasing surprise.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

sec3.htm

Last Updated: 11-Dec-2006