|

Rainbow Bridge

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 6:

Issues and Conflicts II: Rainbow Bridge National Monument and the Colorado River Storage Project, 1948-1974 (continued)

By 1962, the environmentalist rhetoric regarding the bridge was at a fever pitch. In a March press release sent to every member of the Sierra Club as well as Congress, Brower surmised that "no park or monument will be safe from destruction if this betrayal of promises and flouting of the law is allowed to continue." [286] This was the tone of all future environmentalist rhetoric regarding Lake Powell and the bridge. The issue at Rainbow Bridge was larger than one stone arch; to environmentalists it represented a threat to the national park system as a whole and an indictment of the veracity of any agreement with the federal government. If Congress did not mean what it said when it passed laws, Brower concluded, "we might as well close up shop!" [287]

Rainbow Bridge was at the center of a storm. Nothing the Sierra Club or others did worked. Despite huge letter writing campaigns and direct pressure on key committee members reminiscent of the Echo Park battle, Congress continued its tactic of ignoring funding requests from Interior. By the end of 1962 there was no movement on the issue from Secretary Udall or from Congress. In December 1962, the supporters of protection went to court.

The Sierra Club and the National Parks Association (NPA) knew that innundation of Glen Canyon was only a year way. Their only mission was to prevent the diversion tunnels from being gated, keeping the Colorado River flowing around the dam until protective measures could be funded and constructed. Anthony Wayne Smith, then executive secretary and general legal counsel for the NPA, wrote to Udall in August to urge Interior to comply with the legal and moral requirements of the CRSP and avoid litigation. Most interested parties understood that Udall could only demand funding and not appropriate funds. Environmentalists decided that if they could put the Secretary in a sufficiently public legal dilemma Congress might be forced to bail him out by funding protective measures. Smith anticipated that litigation would be expensive and would have to be pursued to the Supreme Court level and so began soliciting financial support from various environmental groups. [288] In November, Udall wrote to Smith, saying his inability to stop the closing of the gates on the diversion tunnels was unavoidable. Udall maintained that he had tried to secure funds for protective measures and that all his requests were not just denied by Congress but forbidden as a condition of general appropriations. He pointed to riders in the annual appropriations acts that stated "no part of the funds appropriated for the [CRSP] shall be available for construction or operation of facilities to prevent waters of Lake Powell from entering any national monument." [289] Congress had made it impossible for Interior or Reclamation to fund any protective proposal. For Smith and Brower, litigation was the only remaining option.

On December 12, 1962, the National Parks Association filed suit against Stuart Udall in United States District Court for the District of Columbia. [290] NPA filed for a preliminary injunction to prevent Udall from authorizing closure of the diversion tunnel gates. The NPA relied on the case of Nichols v. Commissioners of Middlesex County, which held that under Massachusetts law an individual citizen had standing to compel a public official to carry out the duties of that official's office. The NPA reasoned that the defined scope of the duties of the Secretary of the Interior had been expanded by the legal stipulations of the CRSP. Judge Alexander Holtzoff ruled against the preliminary injunction for two reasons. First, the NPA lacked standing to sue. Based on Massachusetts v. Mellon (262 U.S. 447), the Massachusetts rule in Nichols did not equate to a federal rule. Citizens only shared a "general interest" in the carrying out of federal laws and the "general" nature of that interest did not confer on them standing to sue the federal government or its appointed representatives. Secondly, the functions of the Secretary of the Interior in taking measures to preclude the impairment of Rainbow Bridge were discretionary and not ministerial. The specifics of how and when to protect Rainbow Bridge were intended to be determined by the Secretary, not the Court. Consequently the Court could not enjoin the Secretary from actions related to those discretionary powers. [291] What the Court meant was that Secretary Udall was free to make any and all decisions necessary to preclude Rainbow Bridge from impairment—even if environmentalists viewed those decisions as wrong.

Secretary Udall, momentarily victorious, prepared for the NPA to appeal. The Court did make a point of something very important to the environmentalist plaintiffs. In the Conclusions of Law, Judge Holtzoff stated, "The provisions of the Colorado River Storage Project Act remain in force. Their execution lies within the discretion of the Secretary." [292] In the appeal, this opinion might have been troubling for Udall. To help prepare a response, the Secretary employed the opinion of Interior solicitor Frank J. Berry. Berry analyzed the precedents relevant to the Rainbow Bridge funding problems and concluded that Congress' act of defunding protective measures through prohibitive provisos constituted a suspension of Sections 1 and 3 of the CRSP. Berry noted that in United States v. Dickerson (310 U.S. 554, 1939) Congress avoided its commitment to provide monetary bonuses to military re-enlistees by attaching provisos in subsequent appropriations acts limiting the use of available funds. "Not only are you not under any Congressional mandate to keep the diversion tunnels open," Berry wrote, "but your failure to effect closure would be at complete variance with the present state of the law applicable to the Glen Canyon Unit, for the Congress has effectively suspended the pertinent of the [CRSP] and has manifested the intention that construction and initiation of storage should proceed on schedule." [293] Based on this advice, Udall felt prepared for the appeals process.

Udall did not have to wait long for a final answer. Within a month, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court upheld Holtzoff's opinion that the NPA and their fellow plaintiffs had no standing to sue and that the discretionary powers of the Secretary were not a matter of judicial concern. [294] On January 19, 1963, after the Supreme Court refused to grant certiorari in the case, Brower telegrammed Secretary Udall and urged him to keep the diversion tunnels open until some kind of compromise could be worked out. [295] But the Secretary, in his dual capacity as conservationist and preservationist, could not do more than he already had done to protect Rainbow Bridge. Regardless of Secretary Udall's personal belief in the value of protecting Rainbow Bridge, he knew that Congress would never fund construction of protective measures. Two days later, on January 21, 1963, BOR personnel shut the gates of the diversion tunnel on the west bank; the Colorado River rose thirty-four feet behind Glen Canyon Dam. [296] Brower and his fellow environmental activists had enjoyed their greatest victory at Echo Park but suffered their most agonizing loss at Rainbow Bridge.

For its part, the Park Service spent the period between 1960 and 1963 preparing for the development of Glen Canyon NRA (see chapter 7). Park Service personnel knew that they could do little regarding the controversy over protective measures. Memos during this period tended to be concerned with the more practical aspects of park management, such as trail maintenance inside the monument, sanitation, and planning for the inevitable flood of visitors that would come to Rainbow Bridge via Lake Powell. The Park Service understood that it operated under direction from the Secretary of the Interior regarding the issue of protective measures; therefore, the Secretary's policy of pursuing funding while still accepting the reality of Lake Powell was the official line the Park Service also followed. Local Park Service personnel familiar with the topography of the Rainbow Bridge area knew that even if protective measures were constructed, visitors would be able to boat to within a mile of the bridge via Lake Powell. This inevitable rise in visitation compelled the Park Service during the early 1960s to complete a Memorandum of Understanding with the Bureau of Reclamation regarding management policies and authority at Glen Canyon. Regardless of the outcome of the conflict over protective measures, Glen Canyon Park Service personnel knew that new management policies, modified budgets, and increased funding would be critical to handling increased visitation at Rainbow Bridge.

| |

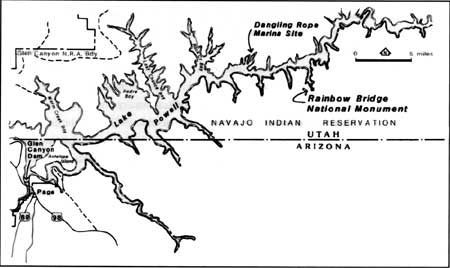

| Figure 30 Rainbow Bridge in relation to Lake Powell (Courtesy of Intermountain Support Office) | |

The mood of the nation changed after 1963. In November of that year, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, providing vivid evidence of life's temporal nature. During the 1960s Congress passed a large number of environmentally sensitive laws. Some scholars have described this period as the "green revolution." Between 1963 and 1970, two presidential administrations and Congress made enormous strides toward protecting scenic and natural resources. During this "green revolution" Presidents Johnson and Nixon signed the Wilderness Act (1964), the National Wildlife Refuge System (1966), the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968), the National Trails Act (1968), and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA, 1970). The NEPA authorized the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and also contained language requiring environmental impact statements (EIS) for federal development projects or non-federal projects on federal land. The mood during the last seven years of the 1960s was optimistic with regard to the environment. Scenic landscapes were regulated by numerous agencies and protective laws. In this climate of national environmental sentiment David Brower returned to the fight for Rainbow Bridge.

During the 1960s, Lake Powell rose slowly behind Glen Canyon Dam. By 1970, the waters from Lake Powell threatened to cross the boundaries of Rainbow Bridge NM. Brower, in his new capacity as director of Friends of the Earth, decided the time was right for a new lawsuit. Brower never forgot that the only real reason NPA lost the previous suit against Udall was the Court's ruling that NPA lacked standing to sue; the merits of the case were never tried. In November 1970, Friends of the Earth, the Wasatch Mountain Club, and Kenneth G. Sleight filed suit in Utah Federal District Court against two parties: Ellis L. Armstrong, Commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, and Secretary of the Interior Rogers C.B. Morton. The suit alleged that the Bureau of Reclamation and the Secretary of the Interior were still legally required to prevent impairment of Rainbow Bridge from Lake Powell. [297]

In the 1970 suit, Friends of the Earth claimed that the water from Lake Powell had risen much further into the monument than anyone had anticipated. Evidence presented during proceedings in 1971 indicated that the water was flowing back and forth into Bridge Canyon. The plaintiffs argued that this represented a clear threat of impairment to the bridge and that stipulations of the CRSP had been ignored.

The case proceeded slowly through pleadings and discovery. Federal attorneys argued much the same as they had in 1962. They contended that Friends of the Earth had no standing to sue and that defunding of protective measures constituted a reversal of the CRSP's Congressional intent clause. But Friends of the Earth seized on a minor point of contention in the 1962 decision: even if the plaintiffs had standing to sue, they could not prove injury sufficient to compel the court to enjoin Udall from closing the diversion tunnel gates. In the 1970 suit, Friends of the Earth felt they had evidence to support a claim of injury, that Rainbow Bridge was being "impaired." In 1973, the plaintiffs filed for a summary judgement in the case. On February 27, 1973, Chief Judge Willis W. Ritter granted summary judgement in favor of the plaintiffs.

| |

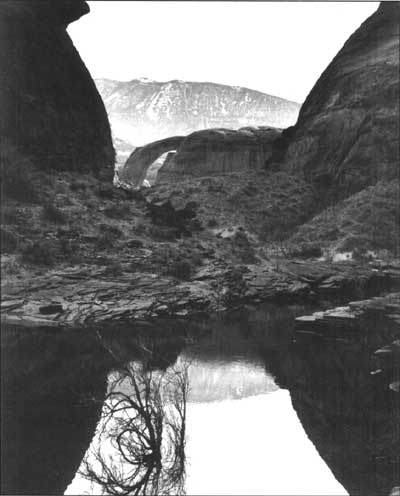

| Figure 31 View of Rainbow Bridge from Lake Powell, January 17, 1971 (Courtesy of Glen Canyon NRA, Interpretation Files. Photo by W.L. Rusho) | |

Ritter's decision validated a number points: that they had standing to sue; that the merits of the case should be tried; the Intent Clause of the CRSP (Section 3) had not been repealed by implication; and, Secretary Morton was bound by the statutory duty to not only protect Rainbow Bridge from Lake Powell but to remove any and all Lake Powell waters from the monument. Ritter issued a judicial order directing Armstrong and Morton "to take forthwith such actions as are necessary to prevent any waters of Lake Powell and the Glen Canyon unit from entering . . . the boundaries of Rainbow Bridge National Monument and they . . . are permanently enjoined and restrained from permitting or allowing the waters of Lake Powell . . . to enter or remain within the boundaries of the Rainbow Bridge National Monument." [298]

The day after the Ritter decision, Senator Frank Moss introduced S. 1057 in the Senate. The bill amended the CRSP by deleting the prohibitive language from Section 3. Environmentalists anticipated this move. Within two days of the Moss bill, messages and telegrams were sent between key members of Congress and Brower and the Friends of the Earth. By March 15, Brock Evans of the Sierra Club assured Brower that the Moss bill would come before Senator Alan Bible's Interior Committee and "be buried for a very long time." [299] The mood regarding Glen Canyon also shifted in the Lower Basin states. To comply with Ritter's decision, which required the removal of Lake Powell water from the monument, meant lowering the lake's maximum elevation. The only feasible way to achieve this end was to release large quantities of water from Lake Powell to the Lower Basin. The prospect of nearly a million more acre feet of water naturally appealed to Arizona and California. [300] Newspapers called the situation a "classic confrontation between conservationists and the federal government." [301]

| |

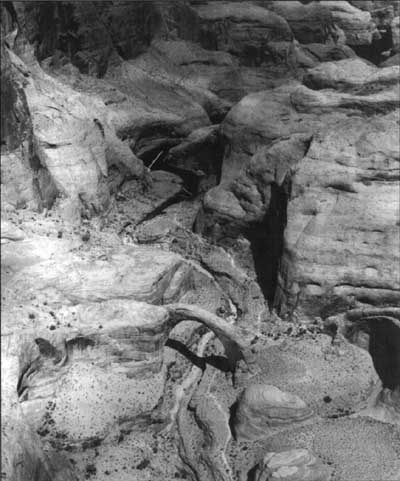

| Figure 32 Aerial Photo of Rainbow Bridge, August 16, 1981. Water is not far from the bridge (Courtesy of Glen Canyon NRA, Interpretation Files. Photo source unknown) | |

The Department of the Interior decided to appeal Ritter's decision. They solicited the Justice department's opinion on how to stay Ritter's order and filed for appeal on March 14. Ritter denied federal requests that he voluntarily stay his own order until the appeal was heard. [302] To comply with Ritter's order, the Bureau of Reclamation began large water releases from Glen Canyon Dam at the end of March 1973. [303] They did not have to comply for long. That summer, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver reversed Ritter's decision and ruled in favor of Armstrong and Morton. The Bureau of Reclamation stopped releasing extra water from Lake Powell. The appellate court decision followed the same line as the 1962 decision, ruling that the power to protect or not protect Rainbow Bridge was discretionary to the office of the Secretary of the Interior. The court also concluded that Congressional defunding of protective measures was tantamount to a modification of Section 3 of the CRSP and the Secretary could no longer be bound by its stated intent.

On January 21, 1974, the Supreme Court refused to grant certiorari and did not hear the case, which Interior and Reclamation interpreted as tacit validation of the appellate court decision. As long as Rainbow Bridge remained vertical, the protective clauses of the CRSP were no longer an issue. Other groups, such as the Navajo Tribe, also filed suits seeking restriction of Lake Powell's water from the monument. The significance of Rainbow Bridge, as a unit of the national park system, was in its role as a playing field for competing public and federal interests. Secretary Udall entered the debate in 1961 with history of activism for both conservation and preservation. But in his capacity as Secretary, he was in charge of two different agencies with different agendas regarding Rainbow Bridge. The Colorado River Storage Project, a massive edifice of water reclamation that affected millions of people, proved too powerful a consideration during the debate over water inundating a small portion of Bridge Canyon. In one of the other important cases involving Rainbow Bridge, Badoni v. Higginson, the courts ruled that the considerations of the CRSP were so important that even infringing on the First Amendment could be allowed (see chapter 5). The Park Service's management goals and policies for the monument evolved quickly during the litigious 1960s and 1970s. After Lake Powell water finally moved under the bridge, the Park Service embraced a management style marked by flexibility and adaptivity.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/rabr/adhi/adhi6b.htm

Last Updated: 07-Feb-2003