|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Wildlife Portfolio of the Western National Parks |

|

BIRDS

ALASKA PTARMIGAN

THE ALASKA WILLOW PTARMIGAN is an Arctic grouse about the size of the ruffed grouse of the eastern United States (length, 15 inches). It has one marked character, namely, the color changes to pure white, except for the black tail feathers, in the wintertime. It is believed that since these birds live in the far North where the ground is covered with snow during many months of the year, their winter coat of white feathers makes them much less noticeable against this snowy background. This concealing coloration is thought by some to be of survival value to the species. Another winter adaptation of the species is the feathering extending down the legs to the base of the toes. This may be an added protection from the cold in winter.

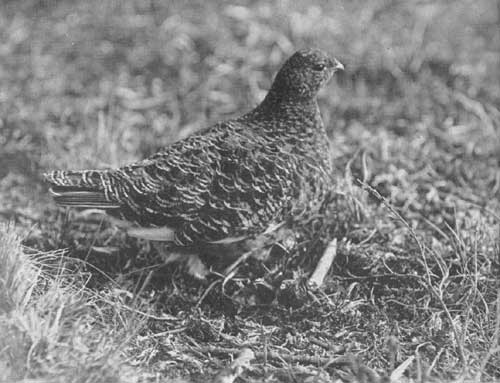

Ordinarily we think of the ladies as being the ones to spend the most time changing their dresses, but in the ptarmigan family it is quite the reverse. In the spring the male assumes his nuptial or wedding dress. First, the feathers on his head and neck change to a rich chestnut color; then, about the time the ptarmigans set up housekeeping, these reddish brown feathers begin to come in on his back. (See illustration.) In fact, he spends most of the summer changing his clothes and then wears his complete summer plumage for only a few weeks. When it is fall he begins to change back into his pure white garb. On the other hand, Mrs. Ptarmigan wastes no time changing her white winter plumage. She puts on her new house dress and goes right to work.

In June 1926, at Mount McKinley National Park, I watched the courtship of a pair of ptarmigans for many hours. The male reminded me of a diminutive turkey gobbler as he strutted about his mate with his head erect, neck extended, and tail spread and sticking out stiffly behind him. The vivid red comb over each eye was carried erect. At intervals he mounted a rock or tussock on the tundra and gave his coarse cackle, which reminded me of someone running a fingernail over the teeth of a stiff comb.

On May 21, 1926, a ptarmigan nest was found on the ground under a dense clump of dwarf birch. This nest was merely a depression wallowed out in the soft reddish moss covering the ground at this spot. While the mother ptarmigan was on the nest the cock seemed to realize that his conspicuous coloration might lead robber gulls or other enemies to the nest. Consequently, he retired to a small thicket about 50 feet from the nest and occupied a roosting place on the ground, where he was well screened and hidden from view. Here he would lie in wait to repel any attacks of thieving gulls or other invaders and to protect his mate.

|

| PHOTOGRAPH. SAVAGE RIVER, MOUNT MCKINLEY NATIONAL PARK, MAY 23, 1926. COURTESY OF MUSEUM OF VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY. |

THE BUFFY-BROWN FEMALE ALASKA PTARMIGAN wastes no time strutting about and crowing. She attends strictly to business, and she has serious business to attend to because there are many enemies that like to eat ptarmigan eggs or ptarmigan chicks, as well as adults. One of the outstanding enemies of the willow ptarmigan in the McKinley region is the short-billed gull. These gulls work in gangs, usually three birds together, flying about over the tundra scouting for ptarmigan nests. When a nest is located one of the gulls swoops down at the brooding female and tries to make her shift over a little on the nest and expose an egg. The second gull then swoops in and endeavors to grab the egg. If it fails, the third gull follows in quick succession. One hen ptarmigan I observed (see illustration) gave a peculiar call for help as soon as these gulls appeared. Upon hearing this call, the cock ptarmigan, who was in hiding near the nest, burst forth like a rocket shot from a gun. He flew directly at the robber gulls, knocking them down with the impact of his body.

Not only are their eggs in danger but newly hatched chicks are much relished by magpies. On June 24, 1926, 1 found a family of four young and two adult magpies searching systematically through the willows for ptarmigan chicks. As soon as the magpies located a pair of adult ptarmigans they retired stealthily and hid in some willows nearby. Here they kept perfectly quiet until the ptarmigan chicks, thinking the danger was past, again began to run about. Then the magpies swooped in, captured the chicks before they could hide, and carried them off to feed their own young. One cock ptarmigan was able to put one old magpie to flight. But in the above instance there were six, and in another case nine magpies working together against two adult ptarmigans. The odds were overwhelming and, by July 10, I found that this ptarmigan family had lost all except one or two of its chicks. Ptarmigans have many enemies but their correspondingly large families (from six to twelve) compensate in the continuation of their race.

Ptarmigan chicks, like young quail, start running about soon after they are hatched. They are exceedingly active and often lead their parents in their search for food. I have found that small insects comprise more than 95 percent of the young ptarmigan's food.

|

| PHOTOGRAPH, SAVAGE RIVER, MOUNT MCKINLEY NATIONAL PARK, JUNE 6, 1926. COURTESY OF MUSEUM OF VERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

wildlife_portfolio/bird5.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jul-2010