Historical Background

The Sodbusters' Frontier

Running the sheepherder a close race for the title of "most despised" in the eyes of the cattlemen was the farmer. The cowboy disdained any labor that he could not perform on horseback, and almost everything connected with farming was done afoot. Despite the cattlemen's scorn, crop failures, Indians, and many other hazards the farmers continued to move into the West. And where they went they built schools and churches and established towns. In short they wanted civilization and brought it with them. After the farmers settled the West the frontier was gone.

AGRICULTURE AND THE MINING FRONTIER

The California rush and subsequent mineral strikes stimulated the development of agriculture, as well as ranching, in many parts of the West. They brought in a large population, which had to be fed, and they increased interest in Western settlement in the East. In most mining areas, farmers and ranchers moved in, or expanded their operations if they had already settled in the region, and cowboys made cattle drives to many of the areas.

|

| Montana homesteader breaking the sod. (Courtesy, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and National Archives.) |

The substantive effect of the California rush on agriculture in that State and on the rest of the West has already been discussed. Many of the other mining rushes had a similar result. Utah Territory is a good example. For many years it was an agricultural island, surrounded by mining-created Territories and States. Taking advantage of these markets, the Mormons extended their farming into the mining areas and prospered as traders and suppliers. Before the Civil War they founded settlements in Nevada, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Idaho. Everywhere they had notable success with irrigation, which influenced other settlers to utilize it.

In various non-Mormon areas of the West, where major strikes occurred, the pattern that had developed in California was repeated. First would come the miners and then ranchers and farmers. When the miners left in search of a new El Dorado, the farmers and ranchers stayed to form a stable population.

Even in the unfruitful desert country of Nevada, the mining boom caused an expansion of agriculture. Farms increased from 91 in 1860 to 1,404 in 1880, when the Nevada mines began to fail. In the arid Southwest, agriculture was also affected to some degree. For example, in Arizona Charles D. Poston irrigated a small plot beside the Santa Cruz River to feed the employees of his Sonora Exploring and Mining Company. Just outside of present Nogales, Pete Kitchen established his famous farm-ranch in the 1850's. Noted for his ham and bacon, he pioneered in large-scale pig farming and was rewarded with handsome profits—and Apache attacks.

In varying degrees, the mining frontier stimulated agriculture in many other sections of the West, sometimes only in certain parts of States or Territories and at different times and places in response to specific local mining strikes.

OTHER AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

The initial agricultural development of some parts of the West had little or no relationship to the mining frontier. A notable example is the Oregon country, a vast region north of California which stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and which Great Britain ceded to the United States in 1846 after more than two decades of joint occupancy. During the 1840's, beginning 6 years before the California gold rush, a few thousand restless emigrant-farmers followed in the steps of Methodist missionaries, who had laid the groundwork for settlement during the previous decade, and crossed the vast and agriculturally forbidding Plains into the Oregon country. Most of them settled in the Willamette Valley, where they engaged in wheat farming.

Disillusioned because the back country of Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas had not proved to be the shining paradise of their dreams and troubled because the Panic of 1837 had shriveled the value of their land and the price of their crops, the emigrants were lured by reports of rich farm country in Oregon much like they had known in the East. Venturesome and courageous and pioneering a long and dangerous overland trek, they refused to accept the Plains as an agricultural barrier as did most other farmers.

In trekking so far the Oregon emigrants of the 1840's, as well as the few thousands who also traveled to California, broke the established pattern of westward advance. From the Atlantic coast to Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas that advance had usually proceeded in small increments of 50 to 100 miles. Now in one great bound it leaped some 2,000 miles. Arid, treeless plains and intermontane basins made up most of the distance—regions isolated from rivers and railroads that were inhospitable and foreign to farmers from humid woodlands. The farmers, who even in the East had avoided the open prairies and grasslands as long as possible, believed that grassland was too sterile to grow trees and hence to grow crops; agriculture had been mainly conducted in previously forested areas and rural life was based on an abundant supply of wood.

Not for many years would the dry farmer subdue the steppe-lands west of the 95th meridian with barbed wire, the windmill, new mechanical equipment, and a unique cultural adjustment. For the land-hungry emigrants of the 1840's, who lacked the technology and knowledge necessary for the conquest of the Plains environment, the Oregon country was the next stop.

Montana is another example of an area where agricultural development was not fostered by mining activities. Farming began there in 1842, some years before the discovery of gold. The Jesuits at St. Mary's Mission, near present Stevensville, were such successful agriculturists that they sold their surplus produce to trading posts along the Missouri. About 1850 they leased the mission to Maj. John Owen and moved to another location in Montana. Major Owen continued to cultivate the land and sold his produce to emigrants using the Mullan Road.

|

| Well-drilling outfit at work on the Plains. Water was a scarce commodity. Either the settler hauled water from the nearest stream or called on itinerant well drillers to solve his problem. Photograph by W. D. Johnson. (Courtesy, U.S. Geological Survey.) |

For another example, in Arizona the first extensive irrigation system had little connection with the mining industry. In 1867 Jack Swilling and several associates began to construct the Salt River Valley Canal, around which the thriving agricultural community of Phoenix arose.

FREE LAND AND OPPORTUNITY ON THE PLAINS

While agriculture was developing on the Pacific coast, in the Intermountain Basin, and through the Rocky Mountain valleys, the Great Plains to the east had remained largely unsettled because of the harsh and strange natural environment and the presence of vast buffalo herds and hostile Indian tribes. Eventually, after the buffalo hunters had done their work, the U.S. Army removed the Indians by force, but the troops could do nothing about the weather, the periodic plagues of grasshoppers, or the other problems.

|

| Accustomed to hilly, forested country, most settlers were awed by the emptiness and loneliness of the Plains. Photograph by W. D. Johnson. (Courtesy, U.S. Geological Survey.) |

To encourage farmers to move onto the Plains, the Federal Government passed a series of land laws. Before 1861 settlers who pushed into the West to acquire land were governed, theoretically at least, by a series of laws that never seemed entirely satisfactory. The laws either did not fit the conditions of soil or climate or they favored speculators and large landholders rather than small farmers. The Land Law of 1820—the basic land law until 1862—had reduced the price of public land to a low of $1.25 an acre and permitted the sale of 80-acre tracts. Thus anyone with $100 cash could buy a farm from the Government.

Despite the cheapness of land, thousands of settlers could not raise the necessary cash. They simply squatted where they chose without benefit of title. As the squatters became more numerous, they pressured Congress to legalize their occupancy by establishing "preemption rights." Prior to 1840 Congress yielded gradually to these demands by granting relief to special groups. Then in 1841 it enacted a general preemption law that gave squatters the right to purchase the lands on which they had settled, and specified that the sale should be at the minimum price.

|

| The sodbuster brought his bride to a sod house on the Plains and raised a family. Beyond the tree belt, sod was the basic building material. Photograph by S. D. Butcher. (Courtesy, Nebraska State Historical Society.) |

The act of 1841 did not completely satisfy the squatters. It did provide that their lands could not be sold to speculators without ample warning, but landgrabbers seriously abused it and often hired counterfeit farmers to preempt the best lands. The genuine farmers had their demands satisfied in 1862, when the Homestead Act became law. This act provided that any American citizen or person in the process of becoming naturalized could obtain 160 acres of Government land by paying only a registration fee. Before the settler could pay the fee he had to live on the land for 5 years, make improvements, and begin cultivation. He also had the option of obtaining title at the end of 6 months by paying the minimum price at that time, but few settlers chose this alternative.

When Congress passed the Homestead Act, it was also engaged in deeding large portions of the public domain to railroad companies, especially to the transcontinental lines that would become avenues of frontier advance after the Civil War. Between 1850 and 1871, to stimulate railroad construction, Congress granted to various companies an area approximately three times the size of Pennsylvania. Notable among these grants were a total of 40 million acres, made in 1862 and 1864, to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads. The Northern Pacific and the Southern Pacific also fared well at the hands of Congress. In many instances settlers found it more advantageous to purchase railroad land than to establish a homestead.

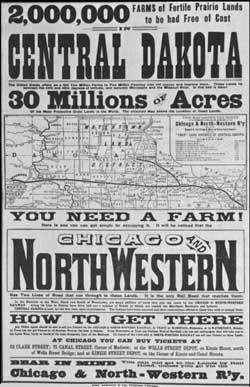

|

| Railroad advertisements lured thousands of emigrants to the West. Many settlers chose to purchase railroad land rather than establish a farm under the Homestead Act. (Courtesy, Chicago and Northwestern Railway.) |

However, large numbers of citizens, the bulk of them from the Mississippi Valley region, and newly arrived foreigners took advantage of the free land offered by the Homestead Act. As one farmer said, "The government bet us 160 acres against five years of our lives that we could not stick it out." The opportunity to acquire a farm at no cost except for the registration fee encouraged farmers and would-be farmers to venture out onto the Great Plains in the face of drought, dust, grasshopper plagues, and blizzards.

Because the 160 acres allowed by the Homestead Act proved to be an insufficient number to earn a living in the arid and semi-arid West, in 1873 Congress passed the Timber Culture Act, which entitled a farmer to acquire an additional quarter section of land simply by planting 40 acres of trees within a specified period of time; later the requirement was reduced to 10 acres. Then in 1877 the Desert Land Act offered sections of land in the desert regions for $1.25 an acre if the farmer could irrigate it within 3 years of the filing date. Only 25 cents an acre was due at filing time; the balance was not due until the conclusion of the 3-year waiting period.

Finally, in 1894 the Carey Act provided for the transfer of Government lands in arid regions, up to a million acres that could be irrigated, to any one State. States accepting the land had to agree to irrigate at least 20 acres of each 160 actually farmed within 10 years. Many Western States accepted these conditions. They usually contracted with private companies for the construction of irrigation projects; these companies then sold or leased water rights to the farmers.

THE GREAT MIGRATION

The flow of farmer-settlers to the West was hastened by a number of favorable circumstances—many of which also stimulated development of the open range cattle industry. These circumstances included the conclusion of the Civil War, removal of the buffalo and the Plains Indians, free land under the Homestead Act, a period of adequate rainfall, increased immigration, the introduction of improved farm machinery, and the building of the railroads. In fact the railroads had as much or more to do with the westward migration as the Government itself. Recipients of millions of acres of Government land, the railroad companies set up "land departments" and "bureaus of immigration," which lured customers and arranged prices, sales, and credit. They spent millions on advertising, much of it not closely related to the truth, and sometimes used high-pressure selling methods.

In the 1870's Kansas gained 347,000 people, Nebraska 240,000, and other Plains States and Territories in proportion. Then came the great deluge of immigrants from Europe. Railroads, steamship companies, and the Western States and Territories themselves promoted the immigration. From northern Europe came Germans, Dutch, Swedes, Norwegians, and Danes. The Minnesota and Dakota regions appealed especially to the Scandinavians. In some areas of the northern Plains, the farmers' frontier was more European than American, even as to the language spoken.

Despite the hardships and financial risks faced by the immigrants, the population of the Plains States increased rapidly. By 1880 Kansas had 850,000 people and Nebraska 450,000. Dakota boomed with the removal of the Indians and the arrival of the railroads. Equally important in the settlement of the Dakota region were the spectacular efforts of Oliver Dalrymple. When the Panic of 1873 forced the Northern Pacific Railway into bankruptcy, company officials decided to promote the sale of railroad lands. They engaged Dalrymple, a skilled wheatgrower from Minnesota, to establish demonstration farms. They provided him with 18 sections of land in the Red River Valley and adequate funds for the purchase of machinery. Using methods similar to those on California's bonanza wheat ranches, Dalrymple imported gangs of laborers and used the best agricultural machinery. With extremely low production costs—about $9.50 per acre—he produced a high yield, for which he obtained a good price. His profits were more than 100 percent. As a result, within 4 years large wheat farms covered most of the Red River Valley, and the population of the Dakotas increased rapidly.

|

| A harvester-thresher at work in the Imperial Valley, California. Newly invented machinery facilitated the conquest of the Plains and produced increased yields. (Courtesy, National Archives.) |

Wyoming, natural cattlemen's country, began to attract a few farmers after 1867, when the Union Pacific Railroad arrived. The farmers achieved some success along the eastern border of the Big Horn Mountains, where water could be diverted for irrigation. Between 1880 and 1890, after the Indian danger ended, considerable development took place; the farmers constructed about 5,000 miles of ditches to irrigate approximately 2 million acres of land. Yet the population of Wyoming grew slowly, and cattle ranching remained the dominant industry. A similar situation existed in eastern Montana.

As the population of the northern Plains increased, farmers also moved into the southern Plains. In Texas, where the State owned the public domain, during the 1870's the number of farms increased by approximately 113,000. Land-hungry settlers then began looking toward the Indian Territory, where millions of acres had been assigned to 22 tribes. Pressure from prospective settlers, as well as from land speculators and railroad companies, eventually forced Congress to modify its Indian policy and open the country to settlement. The pressure of would-be settlers to get into the area was so great that the Army had to keep them out. Finally, in January 1889 the Government compelled the Creeks and Seminoles to sell an unsettled part of their land, and Congress authorized the President to announce that on April 22 the Oklahoma District, as the land was called, would be open to settlement under the Homestead Act.

|

| Sod schoolhouse in Grant County, Oklahoma Territory. When pioneer farmers moved onto the Plains, they built schoolhouses as well as homes of sod. (Courtesy, National Archives.) |

On that date occurred probably the wildest land rush in American history. Within half a day, settlers claimed 1,920,000 acres for homesteading. Guthrie and Oklahoma City sprang into existence before nightfall. The new settlers immediately began to agitate for self-government, and in 1890 Congress created Oklahoma Territory, essentially the part of Oklahoma settled by whites. Gradually the Government opened the lands of other tribes to settlement. On September 16, 1893, it allowed settlers to homestead the Cherokee Outlet, the unoccupied part of Cherokee land, and 100,000 settlers entered that area in one day. In 1907 Oklahoma became a State, numbering half a million inhabitants and combining what had been Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory. The advance of the farmers onto the Great Plains had been completed.

|

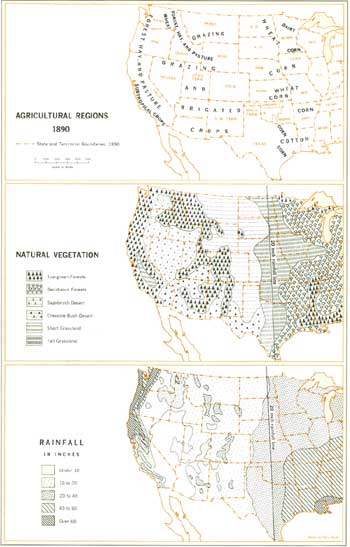

| (click on image for a enlargement in a new window)) |

NEW METHODS AND MACHINERY

The first settlers to venture onto the Plains were forced to invent new techniques to replace the ones they had worked out in the East. Soon exhausting the basically inadequate timber supply, they had to turn from wood to other raw materials to build their cabins and fences. With inventive genius, they cut the tough prairie sod into slabs and built their homes in much the same manner as residents of the Southwest used adobe bricks. They constructed barns and other structures in like manner, and even used sod occasionally for building fences.

Thirsty plainsmen knew that water was a farmer's salvation. Only a few lucky farmers on the Great Plains possessed land adjoining rivers or streams, and they faced the danger of spring floods. Until well-drilling machinery came into common use in the 1880's, the rest had the problem of getting any water at all—even for drinking and for the farm animals. Water was hauled to outlying farms in barrels; it was collected in ponds and in cisterns. Impure ground water caused epidemics of "prairie fever," or typhoid.

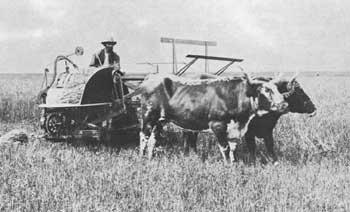

|

| While bonanza farmers worked extensive fields of wheat, small landholders improved their harvests with a Marsh self-binder, drawn by oxen. Across the expanding wheat country in the 1870's sodbusters bought the newly invented agricultural machinery, in a variety of types and models. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

From the beginning, Plains farming required improved machinery. Without a new type of plow to replace the cast-iron plow the prairie sod could not even be broken. John Deere answered this need; by 1857 more than 10,000 of his steel plows, invented in 1837, were being sold annually to prairie farmers. James Oliver's "chilled-iron" plow, an improved model, was invented in 1868. Within a decade more than 175,000 of these plows were in use, and production had soared to 60,000 a year. The next significant innovation was the breaker plow, which differed from the Eastern plow in that it turned over the sod in rather shallow but very wide furrows. Because this plow required more power, oxen instead of horses were required to pull it.

|

| McCormick twine binder float, ready for a Fourth of July parade in Fargo, North Dakota. The exhibition of farm machinery was almost a carnival affair. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

The groundwork for the mechanized agriculture that became a necessity on the flat Plains, which lent themselves so well to mechanization, had been laid in the East during the first half of the 19th century and the Civil War. Wartime labor shortages and high prices stimulated the use of machinery. Even before the war began the cutting of wheat by hand had ceased on almost all large farms, which used Cyrus H. McCormick's mechanical reaper, patented in 1834. Competition between manufacturers and the labor scarcity during the war brought the self-rake reaper to perfection and encouraged experimentation with harvesters and automatic binders. In 1873 the wire binder came into use but it proved unsatisfactory, and by 1880 William Deering had put 3,000 twine binders on the market.

Along with the improved machinery came a new technique of tilling the land, a system known as "dry farming" that evolved at the end of the 19th century. Soil moisture was conserved by careful cultivation. Usually a field was cultivated continuously, but only planted in alternate years. By keeping a dust mulch over the surface at all times, a 2-year supply of moisture could be stored in the ground, provided a windstorm did not blow away the topsoil. Dry farming required extensive tracts of land and the efficient use of farm machinery.

Thus farmers trying to make a start on the Plains had to go heavily into debt for farm machinery, unless they had a great deal of money to begin with—which few had. The use of the new and improved agricultural machinery—common in California's great central valley and later in the "inland empire" of Washington and Oregon—enabled a farmer to increase his acreage and production with less manpower. But the Plains farmer took a greater risk of becoming a slave to his machines, or rather to the mortgage company that lent him the money to buy them, than did farmers elsewhere. For him mechanization was a necessity, but often it failed to raise his standard of living.

|

| Group of farmhands during the busy season on the Barnes bonanza farm at Glyndon, Minnesota, just east of Fargo, North Dakota. Most were itinerants. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

The agricultural development of the Plains was based to a considerable extent upon the work of scientists and inventors who perfected a new process of milling. The Plains, especially in the north, were unsuited for raising the soft winter wheat previously sown in the United States. Hard-kerneled wheat, known as "Turkey Red," imported from the Crimea, grew well in Kansas and Nebraska, while other varieties of spring wheat from Northern Europe produced excellent yields in Minnesota, Dakota, and Montana. But old methods of milling were not effective with spring wheat. Then inventors came to the rescue of the growers. Corrugated, chilled-iron rollers were substituted for millstones and solved the problem. By 1881 Western mills were using the new process and producing fine grades of flour from spring wheat. And grain elevators were constructed by the railroads so that grain could be stored for shipment and loaded into cars mechanically.

|

| Ready to begin harrowing on the Grandin farm, Red River Valley of Minnesota-North Dakota. Photograph by F. Jay Haynes. (Courtesy, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and The Haynes Foundation.) |

GRASSHOPPERS, DROUGHT, AND BLIZZARDS

New methods and machinery did not solve all the problems posed by the Plains environment. Most of the homesteaders ventured onto the Great Plains with the courage of complete ignorance. They planted corn, but it did not grow. They also tried to raise barley, sorghum, and millet, but with only limited success. Finally, wheat became the staple crop, but in dry years serious failures occurred. The inhospitable climate ranged from blizzards to searing heat. Many farm animals froze to death or died from heat and thirst. Recurring droughts turned much of the region into a desert, and grasshopper plagues filled the prairie farmer's cup of frustrations. The worst invasion occurred in 1874, when the whole area, from the Dakotas to Texas, was devastated. The grasshoppers ate everything, leaving, as one farmer said, nothing but the mortgage. But many farmers continued to fight the battle with nature. Many others did not; their byword was "In God we trusted; in Kansas we busted."

|

| Settlers in Custer County, Nebraska. They brought with them everything they owned—a few horses or oxen, a coop of poultry, seeds for planting, a plow. Photograph by S. D. Butcher. (Courtesy, Nebraska State Historical Society.) |

RECESSION, ALLIANCES, AND POPULISM

Farmers on the Plains faced serious problems other than the natural environment. They suffered from the post-Civil War agricultural recession that affected all farmers and had been set in motion by increased agricultural production and the end of wartime inflation and special demand. Adversely affected by the high transportation rates to vital Eastern markets and low prices for their products, they had to pay high prices for manufactured articles, produced by Eastern plants that were enjoying high postwar demand. They were thus forced to buy supplies and farm implements on credit and mortgage their crops and farms at high interest rates. After the disastrous Panic of 1873, creditors foreclosed mortgages, and the money supply tightened severely.

The farmers, attributing many of their misfortunes to corporate monopolies, especially the railroads, took steps to advance their economic interests. The Grange, the first nationwide farm organization, founded in Minnesota in 1868, provided them with a focus for their grievances. It sought by educational and quasi-political means to eliminate the middleman through cooperative buying practices and to initiate State legislation to control the railroads.

|

| Typical sod house in the Cimarron Valley, in southwestern Kansas. The adjustment to a new way of life on the Plains was not easy for most settlers. Photograph by W. D. Johnson. (Courtesy, U.S. Geological Survey.) |

But Western farmers, feeling that the Grange was not sufficiently aggressive, in the middle 1870's began to turn to various other alliances, which prospered throughout the 1880's. [The nationwide development of the Grange and other farmers' alliances will be treated in detail in the volume of this series dealing with the history of U.S. agriculture.] The Populist Party, formed in 1890, synthesized the aims of these alliances, as well as those of the Greenback movement, which had been active from about 1868 to 1884 and had sought to increase farm profits and eliminate debts by convincing the Government to increase the amount of paper money in circulation. The Populist Party was gradually absorbed by the Democratic Party and collapsed in 1896, when the Democrat William Jennings Bryan supported free silver, a key plank in the Populist Party platform.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/prospector-cowhand-sodbuster/intro6.htm

Last Updated: 22-May-2005